The concept of evolution by natural selection fundamentally altered scientific understanding 150 years ago, with its effects extending into politics and religion. While widely accepted in biology, it's as firmly rooted as the Earth's orbit around the Sun in astronomy, yet remains one of the most contentious topics in science. Although the broad concept of evolution is well-established, many details of its billion-year journey are still being uncovered. Here are ten of the most crucial discoveries from the past decade that are helping to complete the evolutionary puzzle.

10. Butterfly Supergenes

Discovery: Butterfly supergenes reveal a previously unknown form of inheritance

The butterfly species Heliconius numata has long been a subject of intrigue. Its population exhibits seven distinct wing patterns, each determined by a combination of numerous genes. When parents with differing wing patterns mate, their genes are shuffled, and these patterns should, in theory, blend. However, the traditional Mendelian inheritance model we learned in school fails to explain this when multiple genes are involved.

In 2011, a team of British and French biologists discovered a phenomenon they termed a supergene – a cluster of eighteen genes inherited as a single unit. Instead of inheriting a blend of genes from each parent, offspring inherit specific dominant or recessive supergenes, allowing the distinct traits to persist. While the butterfly still holds other unanswered questions, such as why seven patterns are needed to ward off predators when only one would usually suffice, at least the how is now understood.

9. Humanzees

Discovery: Evidence of interbreeding between humans and chimpanzees

Chimpanzees are widely regarded as humanity's closest living relatives. The idea of crossbreeding the two species has fascinated people for over a century [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Humanzee], with numerous theories circulating about attempts made by Soviet scientists. Some even claim that a human-chimp hybrid named Oliver lived until last year, though DNA testing has confirmed he was just a typical chimp with human-like traits.

Fortunately for many internet enthusiasts, genetic studies from 2006 indicate that human and chimpanzee ancestors continued to interbreed long after their initial split 6.3 million years ago. In fact, this interbreeding lasted for an astonishing 1.2 million years. These surprising findings could open a new chapter in the exploration of evolutionary history. As study author David Reich noted, “The reason we haven't observed similar events in other animal species may simply be because we haven’t been looking for them.”

8. Old Bat

Discovery: The decades-old mystery surrounding bats is finally unraveled by an intriguing fossil

Bats represent the second largest group of mammals, comprising about one-fifth of all mammalian species. They are the only mammals capable of true flight and have an unparalleled ability to use echolocation, unmatched by any other land-dwelling species. These remarkable traits have long been a source of intrigue in biology—leading to the question, which came first? (For a related question, it’s apparently the chicken.)

In 2003, a pair of fossils were discovered in Wyoming, belonging to a new species called Onychonycteris finneyi, and they displayed several strange characteristics. Unlike modern bats, which typically have one or two claws, this species had claws on all five fingers, possibly indicating an adaptation for climbing in forest canopies. More importantly, this species was capable of flight but lacked the ability to echolocate, providing evidence that flight preceded echolocation in bat evolution. This fifty-two million-year-old specimen, part of the many transitional fossils unseen by creationists, puts an end to decades of scientific debate.

7. Tiktaalik

Discovery: Tiktaalik bridges the gap between fish and terrestrial animals

One of the most significant transitions in the history of life was the shift from water to land. The first animals to make this leap were the tetrapods, meaning creatures with four limbs. These early tetrapods are the ancestors of all modern reptiles, amphibians, birds, and mammals. Scientists have long known that tetrapods evolved from lobe-finned fish, with the coelacanth being perhaps the most famous example. However, for a long time, there was no concrete evidence to show when the soft, fleshy fins began evolving into bony limbs, with estimates ranging from 400 to 350 million years ago.

Tiktaalik, discovered in 2004 in Nunavut, Canada, changed this understanding. Known as a missing link, Tiktaalik was the first fossil that, while still a fish, exhibited early features like digits, wrists, elbows, and shoulders. It represents one of the most transitional fossils ever found. Often referred to as a fishapod by one of its discoverers, Tiktaalik remains a key figure in understanding this evolutionary shift. The elusive fishapod nano and fishapod classic continue to evade discovery.

6. Lice

Discovery: Lice provide new insights into the evolutionary history of mammals

Advances in genetic testing have unlocked insights into the past that were unimaginable just fifty years ago. Lice, which have been causing discomfort on human scalps for tens of thousands of years, provide a unique means to explore this. Lice are highly specialized with claws suited to their hosts, so when a new species evolves, the lice adapt accordingly. This precision in lice speciation allows scientists to create accurate family trees based on DNA, which can be dated precisely using just a few fossil anchors.

DNA analysis of lice was conducted by a (likely very itchy) team of researchers at London’s Natural History Museum, offering fresh insights into the evolution of birds and mammals. The study revealed that bird and mammal lice began diversifying prior to the extinction of the dinosaurs, challenging the prevailing theory and suggesting that mammals might have emerged before the extinction of the dinosaurs. Another equally intriguing possibility is that our lice descend from a lineage that once fed on dinosaur blood.

5. Giant Amoeba

Discovery: The giant amoeba challenges our understanding of when symmetrical life first appeared

Bilateral symmetry, one of the earliest fundamental evolutionary traits in the animal kingdom, is present across various species. For example, if you were to cut a human down the middle, you’d find mostly identical features on both sides. This mirrored pattern is common in animals ranging from flatworms to sharks to elephants. While performing such an experiment might be messy and raise questions, it highlights the ubiquity of bilateral symmetry. This key trait has sparked much debate over when it first appeared, with some of the best evidence being 550 million-year-old sea-floor tracks. These tracks, created by creatures moving in a straight line, were once thought to be made only by animals with bilateral symmetry.

In 2007, researchers from the University of Texas made a discovery that challenged previous assumptions. While diving off the Bahamas coast (certainly a less-than-ideal job, we agree), Dr. Mikhail V. Matz and his team filmed an inch-wide amoeba, a single-celled organism, as it moved along the sea floor. This amoeba propels itself by releasing protoplasm and uses a water-filled core to maintain its shape. The tracks it left behind were remarkably similar to those found in ancient fossils, suggesting that bilateral symmetry may have evolved tens of millions of years later than initially believed.

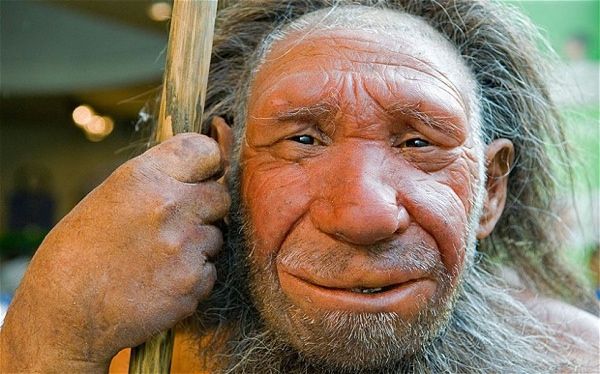

4. Neanderthal Genome Project

Discovery: The Neanderthal Genome Project reveals a closer genetic relationship between humans and Neanderthals

Neanderthals were a species very close to humans. Evidence shows they were likely as intelligent as us, stronger physically, and had a developed culture before disappearing less than 30,000 years ago. Due to their recent extinction, scientists have been able to isolate their DNA. In 2010, a team from the Max Planck Institute in Germany released a draft sequence of the Neanderthal genome, just under a decade after the human genome was mapped.

The most attention-grabbing discovery at the time was the finding that one to four percent of modern human DNA could be traced to Neanderthals, possibly indicating interbreeding between the two species. However, a paper published last year challenges this view, suggesting that these shared genes might come from a common ancestor. The original researcher remains steadfast in supporting the interbreeding theory and has published another paper to reinforce this hypothesis.

In science, open questions are fundamental, and this one is unlikely to be resolved for some time. However, what stands out is that Neanderthals were not significantly different from us.

3. Junk DNA

Discovery: Junk DNA isn't actually junk after all

When the first draft of the human genome was unveiled in 2000, it revealed that ninety-seven percent of the 3.2 billion DNA bases seemed to have no apparent function. The main purpose of DNA is to hold the blueprint for proteins, which is contained in the genes—making up only three percent of the DNA strand. This noncoding DNA had long been known, and the term 'junk' to describe it was first used in 1972. Even Nobel laureate Francis Crick, co-discoverer of the double-helix structure, once suggested that much of life's key components were 'little more than junk.'

In September 2012, the international Encode project revealed a map showing four million switches within junk DNA—these switches regulate protein-coding genes. According to the project scientists, up to eighty percent of the DNA sequence has some biochemical function. Just months after, the implications of this new perspective became evident: scientists at MIT identified a segment of noncoding DNA critical for heart cell development, while other researchers found mutations in noncoding DNA that could be a major factor in skin cancer. These findings open up significant medical possibilities, with much more likely to be uncovered.

2. Oldest Ancestor

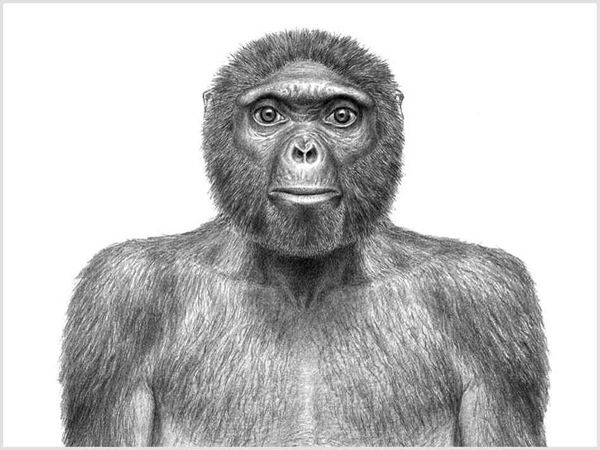

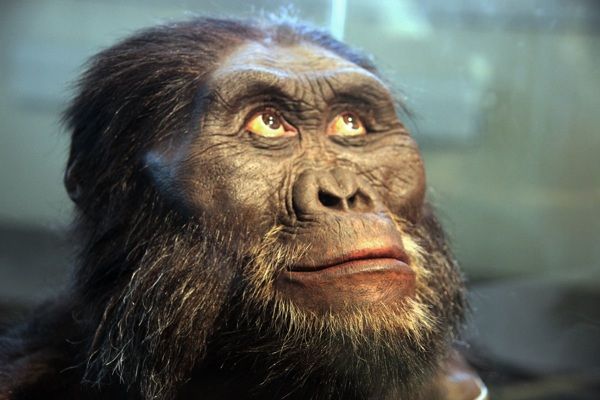

Discovery: Ardi is the oldest human ancestor ever found

While Lucy was once the face of early human ancestry, in 2009, Ardi took her place as the oldest known human ancestor. Ardi, a 110 lb (50 kg) small-brained female, lived more than a million years before Lucy. She was found alongside the remains of thirty-six other individuals, part of a new species called Ardipithecus ramidus. Though Ardi was discovered in 1994, it wasn't until 2009—after over fifteen years of careful analysis—that the full significance of the find came to light.

For years, it was widely believed, based on Charles Darwin's theories, that our common ancestor with chimpanzees would have resembled chimps. However, chimps and humans have had equal time to evolve, and there’s no reason to assume our ancestors were closer to either species. Ardi challenges this long-held idea. She reveals an unexpected blend of both advanced and primitive traits, distinct from chimps or gorillas. As anatomist Owen Lovejoy, who studied Ardi’s remains, said, she shows a 'vast intermediate stage in our evolution that nobody knew about.' And, as we all know, the greatest scientific discoveries often come from unveiling something completely unknown.

1. Lucy’s Baby

Discovery: Lucy’s Baby steals Lucy’s thunder

Lucy, the 3.2-million-year-old skeleton discovered in 1974, is arguably the most famous early human ancestor. Despite being only forty percent complete, Lucy came to symbolize the dawn of humanity. At the time, her species, Australopithecus afarensis, was the oldest known to date from the period after humans and chimpanzees diverged from a common ancestor. However, in 2006, another Australopithecus afarensis fossil was uncovered, overshadowing Lucy’s fame.

This new fossil, though tens of thousands of years older than Lucy, was affectionately named Lucy's baby. The remains, likely of a female who died around age three, are incredibly rare due to the skeleton’s age and completeness. This child, still in the nursing stage, has offered more insights into human ancestry than even Lucy herself. Descriptions of her tiny fingers and knee cap, no bigger than a dried pea, add an emotional layer to this scientific discovery.