While Beowulf and Saint George are celebrated as the most iconic dragon slayers in British mythology, their legendary exploits don't encompass all the dragons found in the rich folklore of England, Wales, and Scotland. Often referred to as 'worms,' many of these mythical creatures are deeply tied to specific locations across the UK. These tales, passed down through generations, form an integral part of local traditions and storytelling.

10. The Tale of the Red and White Dragons

The dragon holds a central place in Welsh culture and identity. A vivid red dragon, symbolizing Welsh pride and nationalism, proudly adorns the country’s flag. Alongside a white dragon, this iconic creature features prominently in The Mabinogion, a cornerstone of British prose literature and a vital compilation of Welsh myths.

Dating back to the 12th or 13th century, the Mabinogion includes timeless stories that have captivated audiences worldwide, including some of the earliest narratives about the legendary Celtic king, Arthur. Among its tales is “Lludd and Llefelys,” which recounts the epic battle between the red dragon and the invading white dragon.

In this tale, the white dragon, a foreign invader, is depicted as a terrifying force. Its shrieks cause miscarriages, while its presence alone devastates livestock and crops. Determined to protect his kingdom, King Lludd of Britain seeks advice from his brother Llefelys in France.

Llefelys instructs Lludd to dig a pit, fill it with mead, and cover it with cloth. Once the white dragon drinks from the pit, it becomes intoxicated and falls into a deep slumber. Seizing the opportunity, Lludd captures the beast and confines it within Dinas Emrys, a hillock in Wales.

A widely accepted interpretation of this story is that the red dragon symbolizes the indigenous Celtic people of Britain, while the white dragon represents the Germanic Anglo-Saxons, who began their invasion of England in the fifth century.

Another interpretation suggests that the white dragon represents the Saxon warlord Vortigern, while the red dragon symbolizes the banner of King Arthur’s army. Regardless, the tale of “Lludd and Llefelys” highlights the strong connection between Celtic Britain and Gaul (modern-day France), potentially dating the story’s origins to a time even earlier than the fifth century.

9. The Dragon of Loschy Hill

“The Dragon of Loschy Hill” is a poignant Yorkshire legend documented by Reverend Thomas Parkinson in his 1888 work, Yorkshire Legends and Traditions. Parkinson recounts how a massive dragon terrorized a forested region, later named Loschy’s Hill, in the parish of Stonegrave. Determined to end the creature’s reign of terror, a courageous knight named Peter Loschy, clad in a unique suit of armor adorned with razor blades, embarked on a quest with his loyal dog to slay the beast.

Confident that the knight would become its next victim, the dragon coiled itself around Loschy’s armor, attempting to crush him. Despite the dragon’s rapid healing abilities, which allowed it to recover from the cuts inflicted by the armor, Loschy managed to sever portions of the dragon’s skin with his sword. His faithful dog then transported these pieces to Nunnington Church.

Loschy and his loyal dog succeeded in dismembering the dragon to such an extent that it could no longer regenerate. Overcome with joy, Loschy failed to notice that his face was smeared with the dragon’s venom. When the dog licked its master’s face, it consumed the poison and perished. Overwhelmed by the toxic fumes, Loschy also succumbed, dying beside his faithful companion.

In gratitude for his bravery, the villagers of Stonegrave laid Loschy to rest beside his dog in Nunnington Church. Stone carvings within the church depict their heroic tale, ensuring their story endures for future generations.

8. The Sockburn Worm

The Sockburn worm is classified as a wyvern, not a dragon. While related to dragons, wyverns in northern European folklore are smaller, featuring a dragon’s head, a snake’s body, bat-like wings, and two legs attached to a lengthy, serpentine tail. Despite their size, wyverns were notorious for their ferocity, and the Sockburn worm was no exception.

Shortly after the Norman Conquest, the Sockburn worm unleashed terror across the River Tees region in County Durham. Utilizing its flight and venomous breath, the creature devastated the Sockburn Peninsula.

Determined to end the wyvern’s reign of destruction, a knight named Sir John Conyers visited a church, offering the life of his only son to God as a sacrifice before the battle. According to the Bowes Manuscript, Conyers not only slayed the wyvern but also gained land and a title for his bravery.

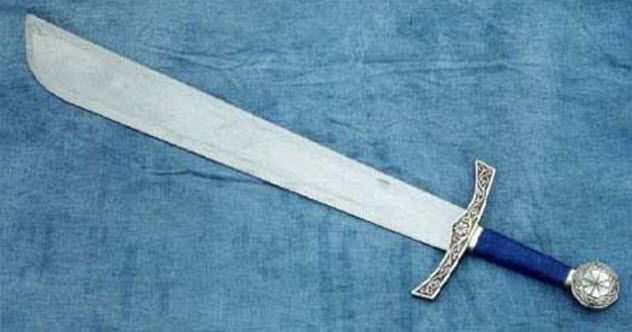

Some historians interpret the Sockburn worm as a raiding Danish warrior, while others view Conyers as a Norman knight who helped solidify Anglo-French dominance in the northeast. Regardless of interpretation, the weapon Conyers allegedly used to kill the wyvern, known as the Conyers falchion, remains on display in Durham Cathedral.

7. The Mester Stoor Worm

The Orkney Islands, situated in northern Scotland, boast an ancient history dating back to the Stone Age. In the ninth century, the islands faced repeated Viking invasions from Norway, eventually becoming a settlement for Scandinavians who played a key role in annexing the islands for Norwegian and later Dano-Norwegian rulers.

As a meeting point for Germanic and Celtic cultures, the Orkneys developed a rich tapestry of folklore. Among these tales is the story of the Mester stoor worm, a distinctly Orcadian legend.

According to the legend, the Mester stoor worm was an enormous sea serpent capable of encircling the entire globe. Its movements triggered earthquakes and other natural calamities. Feared for its toxic breath and its tendency to destroy ships, most knights avoided confronting the beast.

One day, a powerful sorcerer approached the king, promising to slay the sea monster in exchange for the king’s daughter. Unwilling to part with his child, the king instead vowed to grant his entire kingdom to any courageous warrior who could defeat the Mester stoor worm.

The unlikely savior was Assipattle, a simple-minded farm boy who outsmarted the dragon by sailing a ship into its stomach. Once inside, he ignited burning peat against the creature’s liver, causing a massive explosion that eradicated the Mester stoor worm forever.

Legend has it that the dragon’s demise brought a silver lining, as its scattered teeth formed the Orkney Islands.

6. The Bignor Hill Dragon

Little is known about the Bignor Hill dragon, as its name appears only occasionally in historical records. However, the few details available are intriguing. In the 19th century, The Gentleman’s Magazine noted that locals in Bignor Hill, a Sussex area rich with Roman roads, believed an ancient Celtic dragon resided atop a nearby hill.

Some legends describe the surrounding hills as part of the dragon’s folded skin, while others claim the creature’s lair was near a ruined Roman villa. This latter tale is particularly fascinating, as it may suggest the dragon symbolized resistance to Roman occupation, which brought Roman religion to Britain. The idea of the dragon’s Celtic roots also reflects the Christian vilification of pagan traditions.

While the origins of the Bignor Hill dragon remain a mystery, Sussex is renowned for its abundance of dragon stories, making it a rich source of dragon folklore.

5. The Lyminster Knucker

Lyminster in Sussex was once the dwelling place of a knucker. Derived from the Old English term nicor, meaning “water dragon,” knuckers are typically found in knuckerholes, small ponds scattered across Sussex. The Lyminster knucker resided in one such knuckerhole near the prominent Lyminster church.

The knucker first terrorized the area by stealing livestock. It then escalated its attacks, abducting young girls from the village until only the king’s daughter remained. Desperate, the king of Sussex offered his daughter’s hand in marriage to anyone who could defeat the dragon.

The legend offers three variations of the hero. In one account, a wandering knight slays the dragon and marries the princess. Another version credits a local man named Jim Puttock, who kills the beast with poisoned pudding. A third tale tells of Jim Pulk, who uses poisoned pudding to defeat the dragon but succumbs to its venom after failing to cleanse his skin.

These differing accounts underscore the significance of the Lyminster knucker in Sussex folklore. St. Mary Magdalene’s Church in Lyminster is famed for the “Slayer’s Slab,” a tomb believed to hold the remains of the dragon’s vanquisher.

4. The Laidly Worm of Spindleston Heugh

“The Laidly Worm of Spindleston Heugh” originated as a Northumbrian ballad, shared through song in northern England. The tale begins with the king of Northumbria residing in Bamburgh Castle with his family. After the death of his first queen, the king marries a wicked witch. With his brave son, Childe Wynd, away at sea, no one remains in the castle to thwart the witch’s sinister schemes.

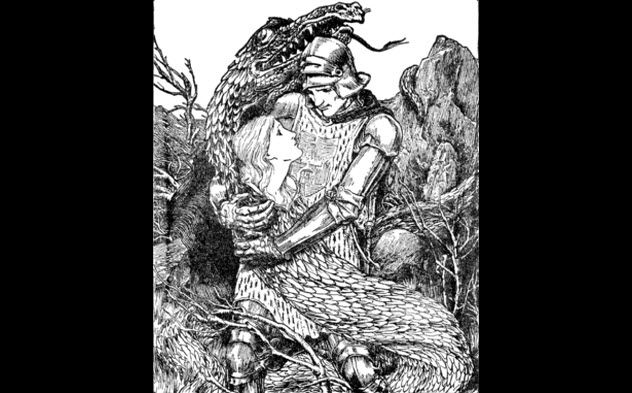

Consumed by envy for Princess Margaret’s beauty, the witch transforms the young girl into a dragon. The princess remains cursed until Childe Wynd returns and kisses the dragon, breaking the spell and allowing him to ascend the throne. In retaliation, Childe Wynd curses the witch, turning her into a toad.

This classic tale has multiple renditions. In one variation, the castle is named Bamborough, and the witch's curse is even more dreadful. Princess Margaret transforms into a ravenous dragon that devours the local livestock. Both versions, however, are inspired by the Icelandic saga of shape-shifter Alsol and her beloved Hjalmter.

3. The Linton Worm

As per 12th-century tales from the Scottish Borders, the Linton worm resided in the “Worm’s Den,” a hill close to the village of Linton in Roxburghshire. At twilight and dawn, the dragon emerged to hunt sheep, cattle, and even humans. All attempts to defeat the beast with weapons failed, and soon, Linton was left desolate.

Upon hearing about the dragon, William (or John) de Somerville, the Laird of Lariston, resolved to take action. As he rode north, de Somerville observed that the dragon devoured everything in its path. However, when encountering something too large to consume, the beast would remain motionless with its jaws wide open.

Recognizing the dragon's weakness, de Somerville commissioned a blacksmith to forge an iron spear with a wheel at its tip. He attached burning peat to the wheel and, riding into the dragon's mouth on horseback, thrust the fiery weapon inside, inflicting a lethal injury.

As the Linton worm writhed in its final moments, its thrashing body shaped the numerous hills that now dot the landscape. To honor his bravery, Linton Church (or Kirk) erected a carved stone to immortalize the tale.

Some accounts place the Linton worm's demise during the reign of King William the Lion, who ruled Scotland from 1143 to 1214. It is said that the king hailed de Somerville as “my gallant Saint George” to bolster his spirits. Additionally, de Somerville's triumph is commemorated not only by the carved stone in Linton Church but also by his coat of arms, which displays a green, fire-breathing dragon atop the tympanum.

2. The Longwitton Dragon

For a period, the residents of Longwitton in Northumberland were denied access to three sacred wells. The reason wasn’t poisoned water but a terrifying dragon that guarded them. The situation only changed when Sir Guy, Earl of Warwick, stepped forward to slay the beast.

Sir Guy and the dragon engaged in a fierce battle that lasted three days. Despite his efforts, Sir Guy grew frustrated as every strike and slash he delivered seemed ineffective. The dragon simply used its magical abilities to heal its injuries instantly.

On the final day, Sir Guy observed that the dragon kept its tail submerged in one of the wells during the fight. Understanding that the sacred waters were the source of the dragon’s regenerative power, Sir Guy lured the creature away from the wells, rendering it defenseless. Once separated from the holy waters, Sir Guy swiftly defeated the dragon.

More elaborate versions of the tale highlight that the wells were renowned across Northumbria for their healing properties, which is why the dragon fiercely protected them. Some accounts also mention that Sir Guy used a magic ointment to shield himself from the dragon’s fiery breath.

1. The Mordiford Wyvern

The tale of Maud and the Mordiford wyvern is a unique and intriguing legend. It takes place in the Herefordshire village of Mordiford, where a young girl named Maud discovers a baby wyvern during her morning walk. She brings the tiny creature home, raising it as a pet and feeding it milk.

As the wyvern matures, it develops a craving for human flesh and starts preying on the villagers of Mordiford. Despite its vicious nature, the wyvern remains devoted to Maud and spares her life. However, even Maud cannot stop the wyvern’s rampage. It settles on a nearby ridge, and its constant travels create the Serpent Path, a winding road leading to the local river.

There are multiple accounts of the wyvern’s end. In one, a member of the Garston family slays the beast in a brutal ambush. Another version claims that a condemned criminal kills the wyvern to avoid execution.