In ancient times, the world was vast and largely unexplored. Embarking on long journeys was both expensive and perilous, often taking several months to complete. Beyond a handful of merchants in pursuit of rare commodities and armies led by glory-seeking generals, few individuals ventured far from their homelands. Information about distant lands was scarce and often distorted through repeated retellings. Tales of foreign peoples grew increasingly fantastical with each iteration.

Below are ten groups of humanoid beings once believed to inhabit the fringes of the known world.

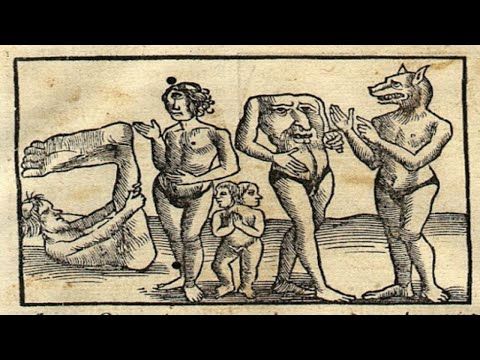

10. The Headless Men

Herodotus, the Greek historian of the 5th century BC, authored extensive historical accounts. However, his works extended beyond mere history, delving into anthropological descriptions of societies the Greeks had encountered or heard of. Due to his occasional inaccuracies, Herodotus is celebrated as both the 'Father of History' and the 'Father of Lies.' Among the many peoples he described were the akephaloi, a race of headless individuals.

Herodotus described a race of individuals with facial features located in the center of their chests, residing on the outskirts of Libya. The Roman author Pliny the Elder referred to them as the Blemmyae. Intriguingly, there existed an actual group named the Blemmyes, who inhabited regions south of Egypt. However, historical records confirm that their heads were positioned where one would typically expect.

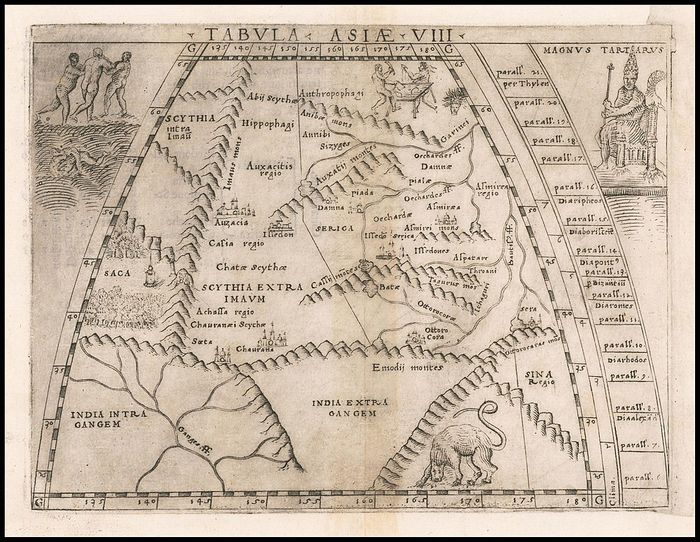

Medieval literature and cartography frequently featured the headless men as a recurring theme. As trade with Africa expanded and knowledge of its inhabitants grew, the supposed location of these headless beings shifted further eastward. Sir Walter Raleigh, in his accounts of Guiana's exploration, mentioned tales of a headless tribe known as the Ewaipanoma, said to dwell near a river in that region.

9. The Androphagi

Not all the peculiar human tribes dwelling beyond the known world appeared bizarre in appearance; often, it was their practices and traditions that astonished the Greeks. The Greek civilization encompassed a variety of societal structures, including democracies, monarchies, and oligarchies. They were deeply curious about the lifestyles of other cultures. Among these, the concept of cannibalistic groups particularly captivated their interest.

Herodotus referenced a tribe that consumed human flesh, naming them the Androphagi, derived from the Greek term for man-eaters. He described them as having 'manners more savage than any other race.' Pliny the Elder also cataloged these man-eaters alongside 'the Agriophagi, who primarily feast on panthers and lions, the Pamphagi, who consume anything, and the Anthropophagi, who subsist on human flesh.'

8. The Gorgades

Pliny the Elder, in his 1st-century AD compilation of universal knowledge, recounted stories from regions scarcely or never visited by Romans. Among these tales, he described the Gorgades, a cluster of islands off Africa's Atlantic coast. Pliny noted that the women of the indigenous population were entirely covered in dense fur from head to toe.

Pliny’s narrative isn’t the sole record of these peculiar beings. Writing a century before him, Pomponius Mela claimed the islands were inhabited exclusively by these fur-covered women, who reproduced without male involvement. These untamed women were described as fierce and powerful, requiring chains to subdue them.

Pliny noted that the Carthaginian explorer Hanno was the one who visited the Gorgades. To substantiate his encounter, Hanno reportedly brought back two pelts of these women and displayed them in a Carthaginian temple. Were these pelts genuine? Could they have belonged to a species of ape encountered by explorers?

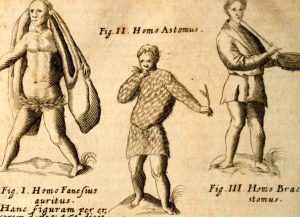

7. The Astomi

The dietary practices of other cultures can be startling to outsiders. Pliny the Elder was particularly intrigued by what people consumed. This fascination is what drew him to the Astomi, a group whose eating habits were unlike any other.

Pliny described this tribe as residing near the Ganges' source in India. Unlike Greeks and Romans, they did not consume conventional food—in fact, they consumed nothing at all, as they lacked mouths. Instead, the Astomi sustained themselves by inhaling the fragrances of flowers and fruits. For sustenance during long travels, they carried scented items to provide energy.

However, their unique diet had a drawback. Strong, unpleasant odors could reportedly be fatal to them.

6. The Panotti

While some individuals might consider surgery to reduce prominent ears, they should feel fortunate not to belong to the Panotti tribe. Their name translates to 'all-ears,' and their ears were so enormous that they served as clothing. On cold nights, they would wrap their ears around themselves for warmth.

Pliny also references the Panotti, but they are not the only large-eared people he mentions. He describes Indians whose massive ears entirely cover their bodies. Additionally, Pliny cites Ctesias, who wrote about an Indian tribe known as the Pandai. The Pandai were covered in white fur that darkened with age and possessed only eight fingers and eight toes. However, their most striking feature was their ears, which extended down to their elbows.

Pomponius Mela locates the Panotti on an island in the far northern reaches of Europe.

5. The Pygmies

To the Greeks and Romans, pygmies were a collection of small-statured tribes found in various parts of the world. Homer, in The Iliad, described pygmies as being in perpetual conflict with cranes—a tale Aristotle accepted as true. Aristotle claimed these pygmies lived underground and rode tiny horses suited to their diminutive size.

Pliny the Elder documented pygmies inhabiting regions from Africa to India. The Indian pygmies were said to stand only 27 inches (68.5 centimeters) tall. They waged war against cranes, as the birds' eggs were a food source. Riding into battle on rams, the pygmies consumed the cranes' eggs to prevent the birds from maturing and retaliating.

In the 6th century, a historian and explorer named Nonossus visited an island in the Red Sea near Ethiopia, home to the Pygmies. These individuals lived without clothing, their bodies entirely covered in hair. Due to their small stature, the Pygmies were extremely shy and would flee from taller visitors.

4. The Abarimon

Following his conquest of the Persian Empire, Alexander the Great led an expedition into India. Among his vast army were scholars, geographers, and philosophers tasked with documenting the newly explored territories. While they gathered extensive knowledge, not all of it appears to have been entirely accurate.

One of Alexander’s men, Baeton, was reportedly assigned to explore the mountain passes into India. In a particular valley, he encountered a tribe whose feet were oriented backward compared to most people. Despite this apparent disadvantage, Pliny notes that Baeton observed they could move with remarkable speed.

Baeton found it impossible to bring any of the Abarimon to Alexander, as they could only breathe the air native to their valley.

3. The Monopods

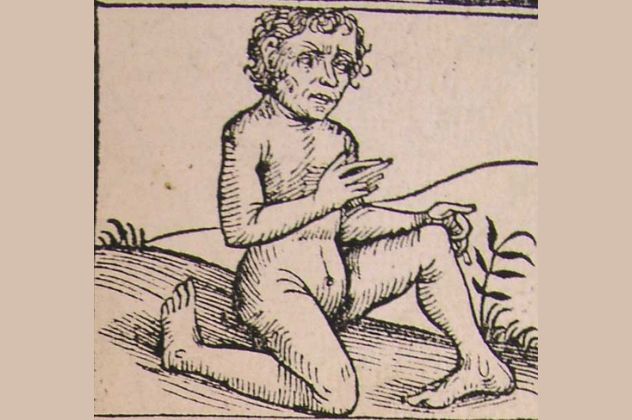

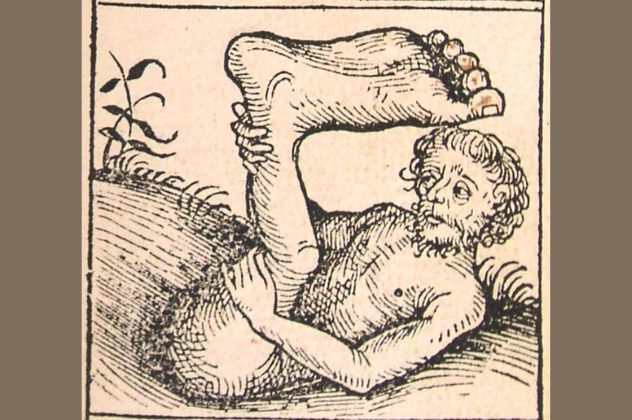

While having only one foot might seem like a disadvantage, for the Monopods, also known as Sciapods, it was a significant advantage—almost as large as their enormous foot. These one-footed beings became a popular symbol for illustrating the bizarre wonders believed to exist at the edges of the known world.

According to Pliny, who cites Ctesias, the Monopods could leap with remarkable agility and were incredibly swift. Their homeland was described as extremely hot and sunny. To escape the intense heat, they would lie on their backs and use their massive feet as umbrellas, creating shade to rest under.

St. Augustine, the Christian theologian, pondered whether humanoid creatures like the Monopods and others were descendants of Adam. He concluded that if such beings existed and possessed human reasoning, they must have souls and, therefore, be part of Adam's lineage.

2. The Cynocephali

When imagining Egyptian deities, people often envision human figures with animal heads, such as cats, crocodiles, or dung beetles. These depictions symbolized the gods' powers rather than representing literal beings. However, some believed that hybrid creatures of humans and animals truly existed. The Cynocephali were a tribe said to have human bodies with the heads of dogs.

Ctesias, a Greek writer who had visited Persia, authored works on India and Persia based on Persian royal archives. Many have questioned the reliability of his accounts. Among the tribes he described were the Cynocephali of India, who inhabited mountainous regions and communicated through howls and barks, yet possessed human-like intelligence and reasoning. Other writers located the Cynocephali in Africa.

During the Middle Ages, some depictions of Saint Christopher portrayed him with a dog's head. This may have resulted from misinterpreting the term Cananeus ('From Canaan') as Caninus ('dog-like').

1. Arimaspi

Beyond the boundaries of the familiar world, strange creatures roamed alongside humans. Herodotus, the 'Father of History,' described giant ants in India, as large as dogs, that unearthed gold. These ants weren't the only beings linked to gold in his accounts.

He also mentioned griffins, majestic hybrids of eagles and lions, who were said to gather gold. Herodotus noted that northern Europe was the richest in gold, though he was unsure of its mining methods. He believed griffins fiercely protected this treasure. The Arimaspoi, a one-eyed tribe, constantly sought to seize the gold, leading to epic battles with the griffins.

The Arimaspi, a one-eyed human tribe, shared ties with the Scythians. Greek artists, depicting clashes between the Arimaspi and griffins, often dressed the former in traditional Scythian attire to emphasize their connection.