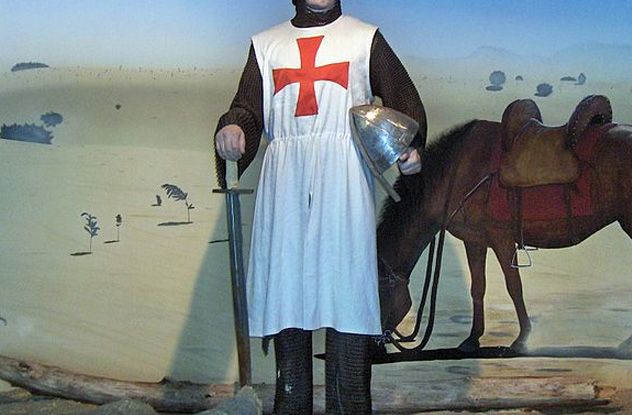

The Knights Templar have captivated global imagination like no other organization, embodying a unique duality of sacred devotion and alleged heresy. Known for aiding the poor and pilgrims, they also accumulated vast wealth and pioneered early banking systems. Despite their eventual trial and downfall, the Templars remain shrouded in intriguing mysteries that blur the lines between myth and historical fact.

10. The List Of 12 Who Escaped

The Templars were famously executed by burning at the stake after being found guilty of heresy in the early 14th century, with many captured and killed en masse. However, lesser-known tales speak of French Templars who managed to evade this fate. Even the modern Templar organization remains uncertain about the full details of these events.

Popular accounts claim that all Templars were apprehended on Friday the 13th in October 1307. Yet, some speculate that a number of them avoided capture. While the order reportedly had around 3,000 members at the time, records only document the interrogations and outcomes of approximately 600. The fate of the others remains a mystery.

Given the impracticality of a nationwide, synchronized arrest operation, many Templars likely had opportunities to flee. Historical records mention authorities chasing escaped knights, and a particular document, recently authenticated through handwriting analysis, lists 12 names that were of significant interest to the authorities.

Historians have linked a few names on the list to notable figures. Humbert Blanc, a Crusader and master of Auvergne, was captured and tried in 1308, denying most charges except the order's secrecy, which he deemed unnecessary. Records indicate he was shackled, but his ultimate fate remains unclear. Other names, like Renaud de la Folie and Pierre de Boucle, appear in trial records, though their significance is hard to determine due to inconsistent name spellings.

The reasons why the remaining individuals on the list were prioritized by authorities remain unclear. One name, Guillaume de Lins, even has a question mark beside it, possibly referring to Gillierm de Lurs, an officer overseeing ceremonies. Spelling variations complicate identification. Similarly, little is known about Hugues Daray or Adam de Valencourt, aside from the latter being an elderly man who joined the Templars twice.

9. Debt, An Assassination Plot, And The Arrests

Among the 12 names on the list is Hugues de Chalon, a figure shrouded in mystery. De Chalon faced trial following the arrests, but his name appears in unusual contexts even before that. As a high-ranking officer in Champagne, he met with the pope in 1302, defying the king's explicit orders to ignore the papal summons. History often shows the dire consequences of defying royal authority.

De Chalon is also referenced in a document linked to Heinrich Finke, the historian who uncovered the list. This document hints at a plot to assassinate the king, allegedly orchestrated by de Chalon and several unnamed associates from a specific Templar faction. However, the details of this alleged plot remain unclear, leaving historians to speculate about its existence and nature.

Another name mentioned in the document is Gerard de Montclair, whose identity remains unclear. Historians have identified a similar name, Richard de Montclair from Cyprus, but no definitive connection between the two has been established.

A plan to assassinate the French king wouldn’t have been entirely implausible. Philip IV was deeply in debt, resorting to extreme measures to manage his financial crisis, some of which predated his reign. He began labeling entire communities as heretics to confiscate their assets, targeting groups like the Jewish population and Lombard merchants. When these efforts fell short, he devalued the French currency by about two-thirds to fund his territorial ambitions.

The Templars’ actions eclipsed widespread public unrest over the currency devaluation, which led to riots. The alleged leaders of these riots were publicly executed as a warning. Shortly after, armed forces were deployed, and the Templars were arrested. While it’s never been definitively proven, their arrests are widely believed to have been financially motivated.

8. What Was The Head Of The Templars?

Accusations against the Templars included the possession of an idol, specifically a head. While most Templars denied any knowledge of such worship, William of Arreblay testified to witnessing a ceremony in Paris where a silver head was placed on an altar and venerated. This head was believed to belong to Saint Ursula, a saint revered by the Templars for her and her 11,000 virgins’ unwavering faith despite facing death and torture.

Adding to the intrigue, Arreblay described the head as having two faces. Other accounts varied, with some interpreting it as the head of Baphomet, while others described it as made of wood, metal, or having black and white features.

The notion of idol worship, particularly of Baphomet’s head, is strongly tied to the accusations during the Templar trials. However, the name Baphomet does not appear in the official arrest warrants. Instead, a variation of the name Mahomed was allegedly linked to the idols at some point.

Amid the Templars’ downfall, a head was reportedly discovered in their Paris temple. Described as a silver-covered skull wrapped in linen and marked “Number 58,” it has been speculated to be one of the 11,000 virgins mentioned by William of Arreblay.

The notion of a mysterious Templar head might be dismissed as mere heresy accusations, but historical records suggest otherwise. They reportedly possessed a head believed to belong to Saint Euphemia of Chalcedon.

This Greek Orthodox saint, martyred by Emperor Diocletian, was revered for her power against heretics. Templar documents reveal that during the Fourth Crusade, relics of Saint Euphemia were acquired in Constantinople and transported to Cyprus. The relic’s journey is well-documented, passing through the Hospital of St. John and Rhodes, eventually reaching Malta by the early 17th century. The Templars viewed the skull as divine proof of their legitimacy, countering claims of heresy.

However, the complete body of Saint Euphemia remains in the Church of St. George in Constantinople, and it’s intact.

7. The Skulls Of The Templars

Nestled high in the French mountains lies Luz, a region of ancient forests, avalanches, and remote outposts once accessible only by electric tram. Known for its waterfalls, snow-covered peaks, and isolation, Luz maintained near-independence until the French Revolution and retained unique freedoms long after. Today, it’s a UNESCO World Heritage Site, celebrated for its rich history of human habitation dating back to at least 10,000 BC.

Luz is also home to one of the world’s best-preserved Templar churches. While the Castle of Saint Marie lies in ruins, the nearby parish church remains impeccably intact, surrounded by crenellated walls, towers, ramparts, and gateways. Its construction reflects the seriousness and skill of its builders.

The church is perched on the edge of the Gavarnie Cirque, a vast valley surrounded by canyons and mountains. Inside the church, 12 skulls are said to belong to Templars who lived in the fortified Luz church when the order for their execution was issued. No names, bodies, or additional details accompany the skulls—only a haunting legend.

Legend has it that each year, the ghost of Grand Master de Molay enters the church and asks if anyone will fight for the order and the temple. One by one, the skulls reply, “None; the temple is destroyed.” While the tale is undoubtedly imaginative, the true story of the Templars in this remote, self-governing village remains a mystery lost to time.

6. What’s Hiding Beneath Rosslyn Chapel?

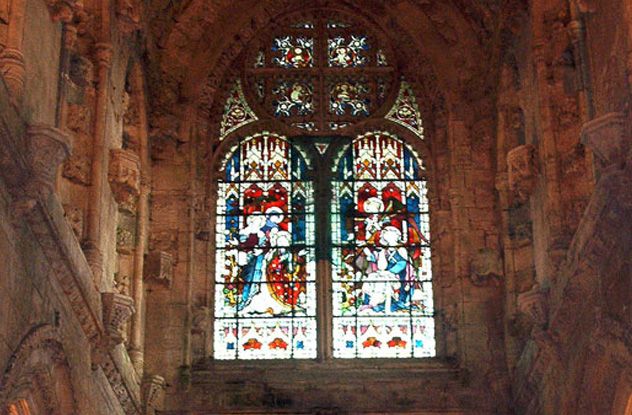

Rosslyn Chapel, officially known as the Collegiate Church of St. Matthew in Midlothian, Scotland, is steeped in Templar legends and mysteries. Renowned for its intricate stone carvings and mystical symbolism, it has inspired countless tales over the years. These range from the wildly speculative (such as being an alien landing site) to the grand and poetic (like the story of 12 Templars resting beneath the chapel, awaiting the world’s call to rise again).

Many of these stories stem from the Sinclair family’s historical connection to the Templars and a 1700s account by Father Richard Hay. He described hidden vaults, secret passages, and tunnels beneath the chapel, allegedly leading to the temporary burial site of the 12 knights. With Sir Walter Scott’s influence, these tales have blurred the line between historical fact and enduring legend.

In 2010, The Glasgow School of Art and Historic Scotland launched a project aimed at unraveling the mysteries of Rosslyn Chapel. Using 3-D scanners, they surveyed the chapel and other World Heritage Sites to preserve its intricate details and support a multimillion-dollar restoration and preservation initiative.

While a full scan of the chapel might have been expected to resolve questions about hidden passages or chambers, it only deepened the intrigue. A vault beneath the chapel, likely constructed in the late 1800s, houses the remains of one of the Earls of Rosslyn, buried in 1937. Additionally, a researcher claims that earlier scans by the US Navy revealed a network of underground tunnels extending away from the chapel.

5. Beneath Temple Mount

The Templars are often linked to legendary treasures like the Ark of the Covenant and the Holy Grail. While many of these tales are fictional, one of their earliest outposts holds genuine archaeological significance. They are believed to have conducted one of the first large-scale excavations beneath Jerusalem’s Temple Mount. Whether this was accidental, during construction, or a deliberate search for something specific remains unknown, as does the question of what, if anything, they discovered.

In 1118, Jerusalem had been under Crusader control for 19 years. The Templars, initially lacking a permanent base, were granted the Temple Mount and its structures by Baldwin II, King of Jerusalem. The site, already a mix of Christian (from Emperor Justinian) and Muslim (from Caliph Omar) influences, was historically significant as a repository for relics and the place where God appeared to David.

Originally, the Islamic temple featured a crescent atop its dome, which the Crusaders replaced with a cross. Upon taking control, the Templars not only adopted the site’s name but also initiated their own construction projects. The sacred rock beneath the dome, believed to mark the spot where an angel descended, remained untouched for 15 years before an altar was added.

The Templars’ mission evolved during this period. Initially tasked with safeguarding pilgrims to the Holy Land, they expanded their role to protect Christian holy sites and relics. Their efforts quickly gained the endorsement of the King of Jerusalem, along with European nobility and clergy.

The rapid rise of the Templars and their widespread support remains a topic of debate. While they had influential backers, some speculate that their discovery of valuable relics demonstrated divine favor for their fledgling order.

While there’s no evidence they found the Holy Grail or the Ark of the Covenant, questions persist. No remnants of the First Temple have been found, but recent excavations revealed a small yet significant artifact: a seal bearing the name of a chief administrator from the First Temple. This discovery confirms the site’s historical significance but also raises further questions about what might have been removed.

4. Henry Sinclair’s Trip To The New World

The Knights Templar are often credited with reaching the Americas before Columbus, though the evidence is tenuous. A key piece of this theory is a 1558 Venetian manuscript detailing the history of the Zeno family.

The manuscript recounts a voyage beginning in 1380, documented through letters by Italian navigators Nicolo and Antonio Zeno. Nicolo, shipwrecked on an island called Frislanda, was rescued by a figure he referred to as Prince Zichmni, a formidable warrior. Nicolo invited his brother Antonio to join him in serving the prince. Over 14 years, they fought alongside Zichmni until they encountered fishermen who had returned after 25 years. These fishermen spoke of a western land inhabited by savages and exotic animals, prompting Zichmni to set sail in that direction.

The tale of Henry Sinclair guiding the Knights Templar to the New World hinges on the manuscript and the claim that “Zichmni” is a variation of “Sinclair.” Frislanda is believed to be the Orkney island of Faray, and Sinclair’s stature would have easily earned him the title of prince.

This theory initially gained little traction. It wasn’t until 1873, when a British Museum librarian revisited the text and its accompanying map, that the idea gained broader acceptance.

The possibility raises questions about the Templars’ activities in the New World, but the uncertainty surrounding Sinclair’s involvement adds another layer of intrigue.

3. The Unknown Knights Of Temple Church

The Temple Church in London, consecrated in 1185, served as the Knights Templar’s headquarters in the city. Designed in the iconic round style inspired by Jerusalem’s Church of the Holy Sepulcher, it was inaugurated with Henry II in attendance. At one point, it nearly became the burial site for Henry III.

The church houses effigies of several historical figures. A 1576 account describes monuments and sculptures dedicated to nobles and knights. Among them are William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke, and his sons William and Gilbert, as well as Geoffrey de Mandeville, William de Ros, and Richard of Hastings. The identities of the remaining effigies remain unknown.

Historical records disagree on the number of effigies, with some describing them as cross-legged or straight-legged. The Survey of London mentions 11 effigies, while other sources cite eight or nine. It’s believed that William de Ros’s effigy was added later, though no records explain when or why this occurred.

In 1842, the effigies were extensively restored, revealing the names of some knights but leaving others unidentified. Some figures appear unarmored or unbearded, suggesting they may not be knights. The reason for the differing leg positions—crossed or straight—remains unclear, though identifying the figures might provide answers.

In 1941, Temple Church suffered damage from a bombing raid. The effigies, severely affected, were later restored, and plaster casts made before the destruction are now preserved at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

The identities of the remaining figures may remain a mystery forever. Once significant enough to earn a place of honor in the Knights Templar’s headquarters, they are now lost to history.

2. The Templars At Bannockburn

The fate of the Templars who escaped the purge has long been a subject of speculation. One theory, partially supported by evidence of Templar activity in Scotland, suggests they fled north and allied with Robert the Bruce at the Battle of Bannockburn.

The Battle of Bannockburn in 1314 marked a turning point in Scottish history, with a decisive victory over the English. Some believe the Scottish triumph was significantly aided by Templar involvement, arguing that Robert the Bruce couldn’t have achieved such a feat alone. Critics, however, dismiss this claim as both inaccurate and detrimental to Scottish pride. Scotland, already a refuge for the Templars due to land grants, became their sanctuary as they fled persecution in France and allegedly fought alongside the Scots at Bannockburn.

Despite the theory, there’s little concrete historical evidence of their presence. Rumored accounts mention the sudden arrival of an unidentified group of warriors as a key factor in the Scottish victory.

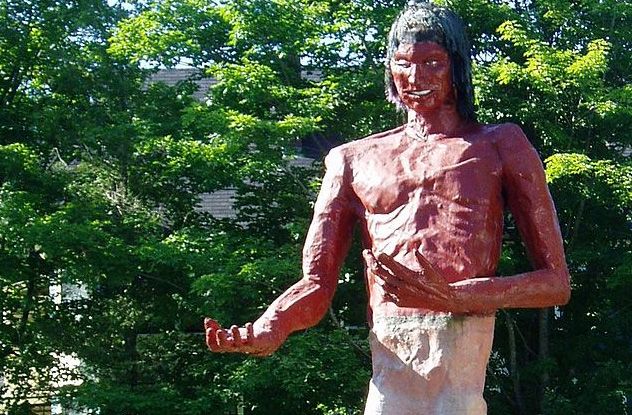

1. Henry Sinclair And Glooscap

The origin story of several Atlantic-region tribes, including the Mi’kmaq, Abenaki, and Maliseet, tells of twins named Glooscap and Malsm, representing Good and Evil. Glooscap created all animals (except the badger) and eventually humans. After defeating his evil twin, he imparted essential survival knowledge to humans before vanishing. However, he promised to return if ever needed.

A 1950s theory suggests that the Glooscap legend was influenced by Henry Sinclair. Frederick Pohl argued that Glooscap’s tales were inspired by a real individual, a notion even some Mi’kmaq representatives find plausible. They propose that the stories may have been shaped around real historical figures, later immortalized as the creator of humanity.

Proponents of this theory highlight connections between Sinclair and the Glooscap myth. Glooscap was described as royalty from a distant island who wielded a sword and had three daughters, much like Sinclair. Additionally, a European presence in Nova Scotia allegedly influenced local diets, with the Mi’kmaq shifting to a fish-heavy diet around the time Sinclair might have been there. They credit Glooscap with teaching them to use nets for more abundant fishing.