For ages, humanity has sought solace in the practice of rituals. These traditions, often rooted in religion, provide a sense of belonging to something greater and timeless. While comforting, some historical rituals were deeply grim. From human sacrifices and hallucinogenic celebrations to attempts at demonic summoning, humanity has devised some truly chilling practices.

10. The Khonds' Ritual of Human Sacrifice

During the 1840s, Major S.C. Macpherson resided among and researched the Khonds of Orissa in India. Over the following decades, he documented beliefs and practices that appeared shocking to Western observers, including the killing of infant girls to prevent future conflicts and accusations of witchcraft.

He also observed, studied, and advocated for the abolition of a sacrificial ritual practiced by some Khond sects. The Khonds revered a creator deity named Boora Pennu, with the Earth goddess Tari Pennu and other gods ranking just below. These deities governed aspects like rain, hunting, and war, and certain Khond groups honored them through human sacrifices. (Other Khonds, however, found the practice abhorrent, believing it was influenced by a false deity.)

Sacrifices were conducted to secure bountiful harvests or in response to significant village calamities. The sacrificial victim, known as a tokki, keddi, or meriah, was often acquired through purchase, kidnapping, or born into families designated for this purpose. Since the victim was believed to attain divinity upon sacrifice, the role was not always seen as tragic. Before the ritual, the chosen meriah was granted unrestricted sexual freedom within the village, with the act considered a divine blessing by the women’s families.

The ritual spanned three to five days, beginning with the shaving of the meriah‘s head and a grand celebration. The next phase involved bathing, dressing in new attire, and a procession, culminating in the meriah being tied to a stake, adorned with flowers, oil, and red dye, and revered by the community. Prior to the final act, the meriah was given milk. His limbs were broken to prevent resistance, and after the priest initiated the sacrifice, the body (excluding the head) was divided and buried in fields requiring divine favor.

Following the sacrifice, a buffalo was offered, and its remains were left as a tribute to the spirit of the meriah.

9. The Initiation Ceremonies of the Eleusinian Mysteries

The Eleusinian Mysteries were a series of ancient rituals that persisted for nearly 2,000 years, ceasing around AD 500. Central to these practices was the tale of Persephone, abducted by Hades and destined to spend part of each year in the Underworld, symbolizing the ancient Greek interpretation of winter.

To join the cult, one only needed to speak Greek and have no history of murder. Beyond these criteria, the cult welcomed everyone, including women and slaves. Initiation rites granted access to the cult’s hidden wisdom, much of which has been lost over time. However, details of the initiation ceremony have survived.

The large-scale initiation in Athens commenced on the 15th day of what is now September. The following day, potential initiates, along with their sacrificial animals, were sent to the sea for purification. (This process wasn’t always safe, as evidenced by a 339 BC incident where a shark attacked and killed one initiate.) After a three-day break, the group embarked on a 24-kilometer (15 mi) journey filled with singing, music, and invocations to Iacchus, a figure linked to Dionysus, to mark the arrival of night.

The following day began with initiates carrying sacrificial bulls to the altar. Over the subsequent days, participants were cleansed and led into the final rites. The lower-level ceremony involved a dramatic reenactment of the myth of Persephone and Demeter. The higher-level rituals remain more enigmatic, though evidence suggests they included extensive dancing and elements of terror, possibly due to the consumption of a mind-altering substance.

Upon completing their journey to Eleusis, initiates consumed a beverage known as kykeon. The exact composition of this drink is debated, but it is known to contain barley and pennyroyal, likely inducing hallucinogenic effects. The barley may have been contaminated with ergot, a parasite, producing sensations akin to an LSD experience.

8. The Aztec Ritual Sacrifice to Tezcatlipoca

The Aztecs are renowned for their practice of human sacrifice, though much about their sacred ceremonies remains unknown. Diego Duran, a Dominican priest, extensively documented Aztec rituals based on interviews with participants. His accounts depict human sacrifice as a theatrical spectacle, meticulously orchestrated and deeply symbolic.

Aztec sacrifices occurred with surprising regularity. Duran, along with Franciscan missionary Bernardino de Sahagun, detailed a festival involving the sacrifice of a man embodying the god Tezcatlipoca. Chosen from captured warriors, the candidate had to meet strict criteria: physical beauty, a slim build, flawless teeth, and unblemished skin. Any imperfection, including speech issues, disqualified him. If he gained weight during his year-long preparation, he was forced to drink saltwater to shed the excess.

Following a year of training, the chosen one was dressed as Tezcatlipoca and given the god’s name. He lived in the temple, worshipped by the elite, and led city parades, though he was caged at night to prevent escape. Twenty days before his sacrifice, he was given four wives and his hair was styled like a warrior captain’s, adorned with a heron feather.

On the sacrificial day, four priests restrained him while a fifth removed his heart and cast it at his face. His body was then hurled down the temple stairs, symbolizing his elevation to godhood and subsequent transformation into divine sustenance. His head was later severed, pierced, and displayed on the city’s skull rack, marking his final metamorphosis.

7. The Saint-Secaire Mass

Sir James George Frazer, a Scottish anthropologist, explored the progression from magic to religion and eventually to science. In his influential work *The Golden Bough*, he described a chilling dark mass performed in the Gascon region of France during dire times. Only a few priests knew the ritual, and most refused to perform it, as it was believed to condemn their souls irreparably. Only the pope could absolve those who dared to conduct the Mass of Saint-Secaire.

The mass took place in a derelict or abandoned church, beginning at 11:00 PM. The priest recited the standard mass backward, concluding at midnight. The communion host was black, and instead of wine, the priest and attendees drank water from a well that held the remains of an unbaptized infant. When making the sign of the cross, the priest used his left foot to draw it on the ground. Frazer noted other elements of the ritual, so horrifying that witnessing them would allegedly render a devout Christian blind, deaf, and mute for life.

The mass was performed with a specific target in mind. Once completed, the victim would gradually fall ill, wasting away until death. Physicians could find no cause for the illness, and no one would suspect the curse of the dark mass as the source.

6. Kawanga-Whare

In Maori tradition, a ceremonial ritual is essential to ensure the safety of a new home for its occupants. Since the trees used in construction are under the protection of Tane-mahuta, the forest god, the builders must seek protection from the gods’ potential anger.

Throughout the construction process, meticulous care was taken with wood chips and shavings. These were never used for cooking fires, and workers avoided blowing away sawdust, instead brushing it aside to preserve the purity of the trees and avoid contaminating them with their breath.

After the house was completed, a tohunga recited prayers over the new dwelling, releasing the sacred wood from the forest god’s protection. Another chant followed, dispelling any enchantments left by the tools used in construction. The final incantation was a plea to the gods to safeguard the house and its residents. Once the rituals concluded, the house became an extension of Tane-mahuta. A woman was the first to enter, ensuring safety for all women, and traditional foods were consumed while water was boiled to confirm the interior was secure.

This account, based on a 1908 witness, omitted a significant historical aspect of the ritual—child sacrifice. The Taraia recount a tale of a man who sacrificed his own child, burying them beneath a house post. Another version claims the man’s child was spared, and a slave’s child was sacrificed instead.

The sacrificial element varied by region. In some cases, the victim was buried alive near a support beam, left to uphold the house. Others were killed before burial, and some were crushed under stones. Victims often came from families obligated to provide sacrifices. Reverend W. Gill documented a man ostracized because his grandfather had refused sacrifice, leading to his brother taking his place and all descendants being permanently shunned.

5. The Mithras Liturgy

The Mithras Liturgy blurred the lines between spell, ritual, and religious ceremony. Discovered in the Paris Papyrus, this text remains enigmatic. The relationship between the Persian Mithras, the Roman deity, and Egyptian gods and symbols is unclear, leaving scholars puzzled. Despite this, the liturgy offers a chilling glimpse into the practices of the mystery cult.

The ritual aimed to elevate an individual through the celestial realms, bringing them into the presence of the gods. Mithras presided at the pinnacle, and the journey involved navigating past gatekeepers and traversing the domains of Earth, heaven, and beyond into supraheaven.

While “heaven” might evoke positive imagery, this was far from the case. The liturgy included prayers and commands to protect against hostile celestial beings who opposed the intruder’s ascent. A key phrase, “Silence! Silence! Silence! Symbol of the living, incorruptible god, protect me, Silence! Nechtheir Thanmelou!” was meant to shield the traveler, while also asserting their divine status.

The ritual unfolded in several stages. Following an introduction, the participant’s spirit journeyed through the four elements, encountering thunder and lightning, before confronting the guardians of the heavenly gates, the Fates, and ultimately reaching Mithras.

The liturgy also provided guidance for crafting protective amulets, preparing a magical cake for the scarab ritual, and performing breathing exercises for the celestial journey. Only after navigating realms filled with wrathful deities and heavenly chaos could one encounter Mithras, depicted with fiery hair and clad in white. Even then, seekers required protection to receive his divine revelation and achieve deification.

4. Bartzabel Working

According to Aleister Crowley, Bartzabel is a demon embodying the spirit of Mars. Crowley claimed to have summoned and communicated with the entity in 1910, during which Bartzabel allegedly predicted large-scale wars originating in Turkey and Germany, leading to widespread destruction.

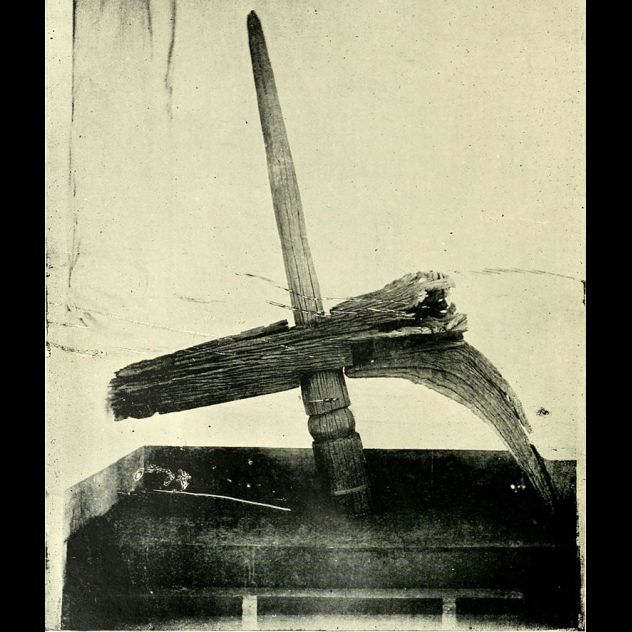

Though Crowley only recalled this encounter in 1914, he documented the ritual for summoning Bartzabel. This included instructions for drawing a pentagon and circle, inscribing demonic names, and creating the Sigil of Bartzabel. The ritual required specific attire, numerous sigils, and an altar equipped with a spear, torch, holy oil, and symbolic imagery.

The ritual was an elaborate sequence of invocations and actions, featuring phrases like, “May the Names of God that encircle us, Be our proof that He has heard us!” Participants circled the altar bearing weapons. The ceremony began with consecrating the space, followed by preparing materials, and culminated in summoning the spirit. The final segment outlined interactions with the demon, including Crowley’s recorded dialogue with Bartzabel, who was eventually dismissed.

In 2013, Brian Butler, a performance artist from Los Angeles, conducted the ritual before a crowd of thousands, marking the largest audience ever to witness one of Crowley’s ceremonies. A blindfolded and bound individual served as the vessel for the demon’s spirit. According to Butler and attendees, the event proceeded flawlessly.

3. Capacocha

The Capacocha ritual was an Incan tradition of child sacrifice, typically reserved for extreme circumstances. Spanish conquistadors documented that the victims were often the children of chiefs, chosen during crises like droughts, famines, or the death of an emperor. Being selected for sacrifice was considered a great honor, with only the most flawless children deemed worthy of deification. Their families gained an elevated social standing as relatives of a divine being.

Once a child was chosen, a procession led from their village to Cuzco, the center of the Inca Empire. Extensive preparations followed, including constructing a sacrificial platform, burial site, and additional structures at the mountain’s base. The child’s final resting place was a tomb-like chamber filled with ceremonial offerings.

On the appointed day, the child was given chicha, a corn-based alcoholic drink, before being taken to the mountain platform. Archaeologists debate the exact process, but many victims show skull fractures, suggesting they were struck unconscious before succumbing to exposure. Evidence of bronchitis, sinus damage, and altitude-related illnesses indicates the children were unaccustomed to the high-altitude burial sites. Traces of vomit and feces on their clothing suggest resistance, and some, like the Llullaillaco boy, were bound or strangled. Spanish accounts of ritual violence align with archaeological findings, further corroborating their testimonies.

Though it offered little solace to the families or the children, the rituals surrounding these well-dressed, well-fed, and cared-for children were performed out of perceived necessity. They served as a bridge between the natural and supernatural realms, a means to influence the destiny of an entire community. Through their sacrifice, the children were elevated to the divine status of deities.

2. Nazca Trophy Heads Ritual

Examine traditional art from the Peruvian Nazca (or Nasca) culture, and you’ll notice a recurring, unsettling theme—trophy heads. Archaeologists have analyzed both artistic and physical evidence to uncover the rituals associated with these heads, revealing a grim and macabre practice.

The Nazca were one of only two South American cultures known to prepare trophy heads for ritual use. (The other was the Paracas.) After severing the head with an obsidian knife, they removed bone fragments, extracted the eyes and brain, and created a hole for a rope, often used to attach the head to a garment. The mouth was sewn shut, and the skull was stuffed with cloth.

The preparation of the heads was likely the initial stage of the ritual, centered around a shaman who acted as a mediator between the living and the afterlife. While archaeologists lack a definitive timeline, numerous illustrations depict key moments. The heads frequently appear alongside cacti, large storage jars, and individuals consuming ritual beverages, suggesting these drinks, likely hallucinogenic and derived from the San Pedro cactus, played a pivotal role in accessing the spirit world. Other images show processions and the use of instruments like drums, trumpets, pipes, and rattles.

The Nazca culture evolved from the earlier Paracas civilization, both linked to a figure known as the Oculate Being. This central religious icon features an oversized head and eyes, a protruding tongue, and is adorned with snakes. It often grasps a trophy head or the tools used in their creation.

The ritual use of trophy heads concluded with their burial. Archaeologists have uncovered groups of these heads, ranging from three or four to over 40, sometimes buried inside jars.

1. The Sacrificial Messengers of the Unyoro

James Frederick Cunningham, a British explorer residing in Uganda during colonial rule, documented his experiences with various local cultures. In his book *Uganda and its Peoples: Notes on the Protectorate of Uganda*, he detailed a ritual performed by one group to honor the death of a king.

A pit measuring approximately 1.5 meters (5 ft) wide and 4 meters (12 ft) deep was dug. The king’s bodyguard would venture into the village and seize the first nine men encountered. These men were thrown alive into the pit, followed by the king’s body, wrapped in bark cloth and cowhide. The pit was then covered with another piece of cowhide, secured on all sides. A temple was constructed over the grave, serving as the residence for the king’s surviving servants and their descendants.

The concept of human sacrifice as a means to provide messengers or guides for the deceased is ancient, but Cunningham expressed astonishment at the method of selecting sacrifices and sealing them within what would become their tomb.

Cunningham also documented a custom practiced by another group, which shed light on the challenges faced by translators. When someone died, their name was never spoken again, even if it was a common word like an adjective or animal name. The word was eliminated from the group’s vocabulary and replaced with a new term, creating significant difficulties for outsiders attempting to comprehend their language.