In 2012, a phantom island appeared on Google Earth, located just north of New Caledonia in the South Pacific. These islands aren’t mere products of medieval fantasy. Unlike mythical lands, phantom islands often confuse geography with folklore. These islands once appeared on maps, and for a time, geographers believed them to be real. Some were simple errors that were later corrected, while others were entirely fabricated. Regardless, these islands have left a lasting impression on the collective human imagination.

10. Thule

Around 325 B.C., the Greek navigator Pytheas set sail from his home port of Massalia (modern-day Marseille), heading into the Atlantic and traveling north. He was the first classical writer to describe Britain, which he called Britannia, or Pritannia, and the island to the north of it, which he named Thule.

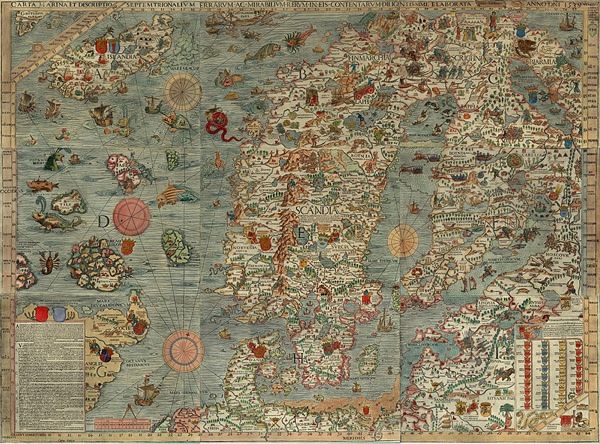

Unfortunately, Pytheas’ original writings are lost to history, leaving us only with references to his account by the geographer Strabo and other classical authors. Strabo believed Thule to be a fabrication and dismissed Pytheas’ description of seas to the north being filled with ice as nonsense. Ptolemy included Thule in his world map, published around A.D. 100, in his work Geographia. After being translated by Florentine scholars in the 1410s, Thule appeared consistently as a large island north of Britain on maps well into the 17th century. Scholars suggest that if Pytheas did indeed travel north of Britain and discover an island, it was likely one of the Shetlands, the Faroes, Iceland, or even the Norwegian coast.

9. St Brendan’s Isle

Around A.D. 530, the Irish monk Brendan and his companions (whose number ranged from eighteen to 150) set out across the Atlantic to evangelize and search for Paradise. For seven years, they lived on an island blessed with a perfect climate, friendly inhabitants, and abundant nature. While the event is believed to have occurred, the earliest written accounts of this journey only appeared three centuries later.

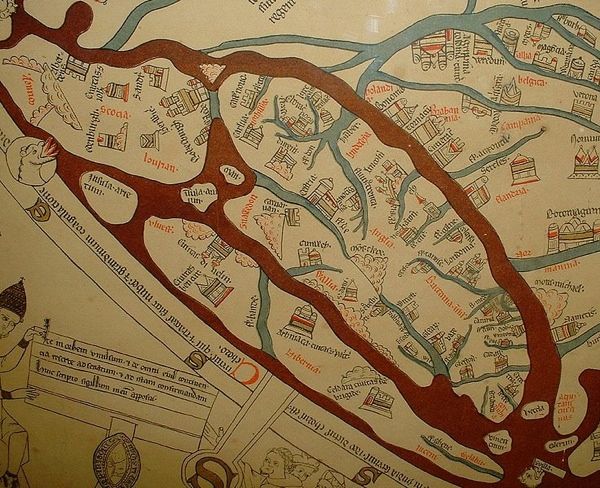

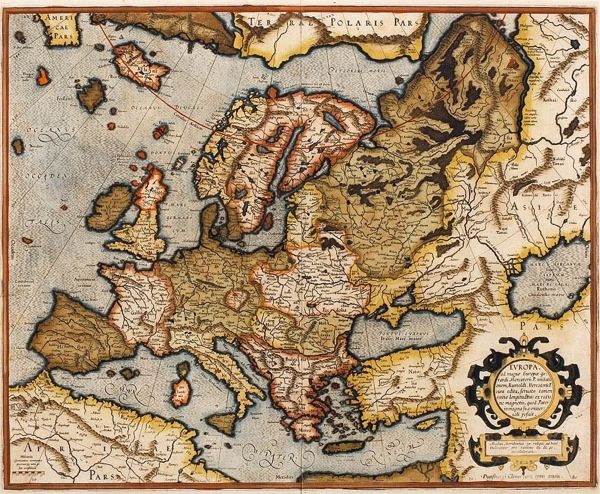

St Brendan’s Isle features prominently on the famous Hereford Mappa Mundi, a key map from the Medieval period, but it was even more frequently depicted on portolan charts—maps made for navigators. It also appeared on 17th-century maps by Mercator and Ortelius and was included in the 1707 De Lisle map. Typically located west of the Canary Islands, there was a lingering belief in its existence, even as mapmakers in the Age of Enlightenment gradually conceded that the island likely wasn’t real, though they were reluctant to completely dismiss the idea.

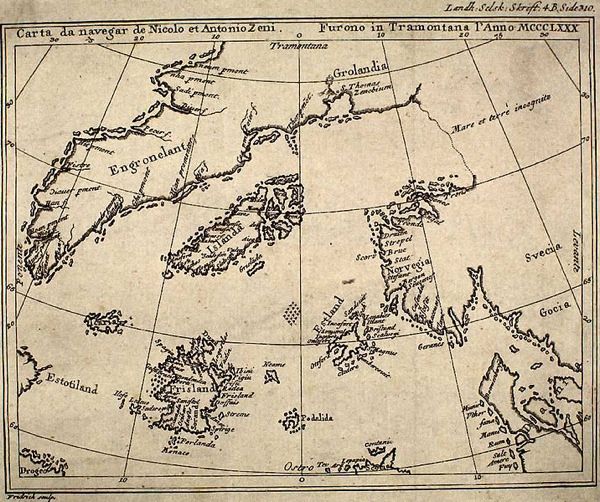

8. Frisland

In 1558, the Venetian Nicolo Zeno published a map and a series of letters he claimed were from two of his ancestors, Antonio and another Nicolo, who had navigated the North Atlantic around the year 1400. The letters, mostly written by the elder Nicolo to Antonio, described an island named Frisland. According to the map, Frisland was positioned roughly halfway between the northeastern tip of Scotland and Norway. Despite frequent conflicts with nearby islands and Greenland, Nicolo seemed to be thriving and encouraged Antonio to join him.

The authenticity of the letters was questioned when they were first published, but that didn’t prevent reputable cartographers from including Frisland on their maps. It often appeared exactly where Zeno indicated, though some maps placed it much farther west, almost within North American territory. A few maps even depicted named bays, mountain ranges, and towns.

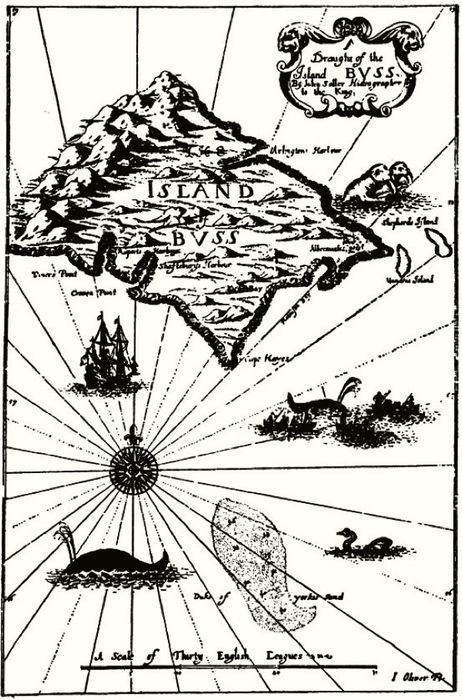

7. Buss

The quest for a north-west passage from Europe to Asia gained serious momentum in 1576 when Martin Frobisher embarked on his expedition to find it (although earlier attempts had been made). During his second voyage, one of his ships, the Emmanuel, passed by an island that its captain, James Newton, described as “appearing fertile, full of forests, and a vast open country.” The island was named Buss, after the type of ship the Emmanuel was. (Someone aboard apparently had a lack of creativity—it’s like naming a place ‘sedan island’ just because you passed it in a sedan.)

Buss was marked on maps, but despite multiple searches, it wasn’t until 1671 that another British sailor, Thomas Shepard, actually landed on it. He named several locations in honor of his patrons at the Hudson Bay Company. However, when Shepard attempted to return to the island, he couldn’t find it again. Buss soon disappeared from maps, and the prevailing theory was that it had sunk beneath the ocean. By the mid-19th century, cartographers accepted it was non-existent and stopped including it on maps.

So what did Shepard and the crew of the Emmanuel actually see? Given the inaccurate longitude measurements of the 17th century, it’s likely that Frobisher and Shepard encountered different locations they mistakenly believed were the same. These could have been promontories of Greenland or islands that were already known. An alternative theory suggests that Buss Island might have the extraordinary ability to rise and fall beneath the waves, waiting to reappear at some point in the future.

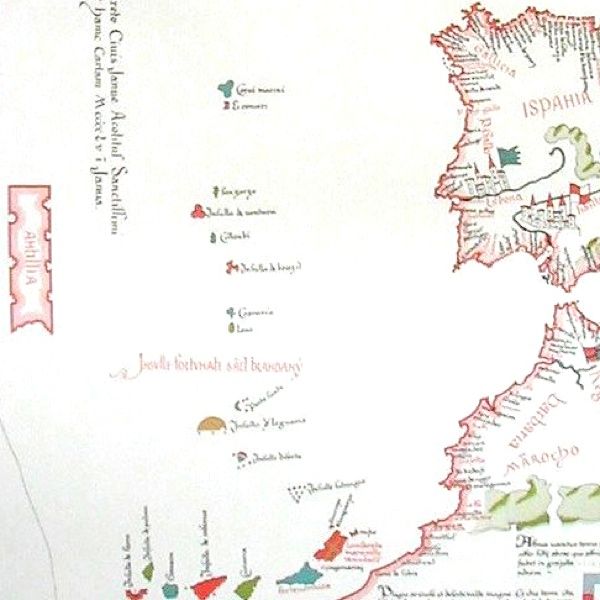

6. Antillia

During the Middle Ages, as Islam gained strength and the Church became more corrupt, the idea of an island in the Atlantic where Christianity remained untainted became incredibly appealing. According to legend, when the Muslims invaded the Iberian Peninsula in A.D. 711, a group of bishops, fleeing with their followers, sailed into the Atlantic and discovered an island where they settled. They named it Antillia, or the Island of the Seven Cities, a Christian paradise where both the people and the land were blessed.

This island is the first on this list to have existed in the realm of imagination before it was ever placed on maps. In the 15th century, it was frequently depicted in the middle of the Atlantic, midway between Europe and Asia. The mapping of the American coast didn’t completely extinguish the belief in Antillia. Even some post-Columbus maps continued to show it. In his 1530 work De Orbe Novo, the Spanish historian Peter Martyr d’Anghiera claimed that a traveler who had spent time in Antillia stayed with Columbus and shared valuable information with him prior to his 1492 voyage.

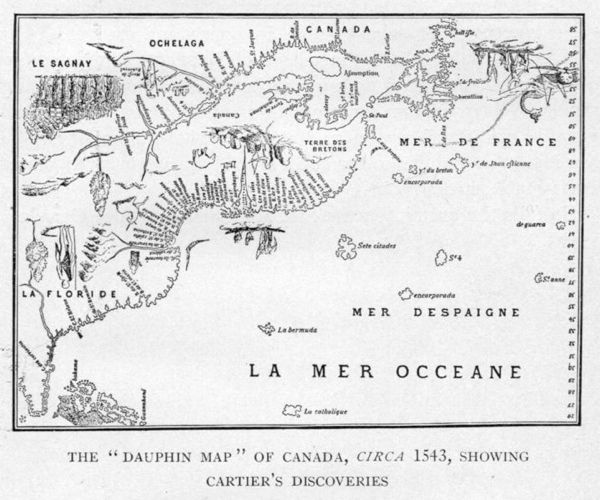

5. Island of Demons

If islands like Antillia or Saint Brendan’s Isle seemed plausible to the medieval mind, then so too did their dark counterpart: an island cursed by demons. In fact, there were two such islands: Satanazes, often depicted just north of Antillia, and the Isle of Demons, located off Newfoundland. The latter first appeared on maps in the 16th century. Though these islands were sometimes confused, Satanazes began to lose credibility after the discovery of America, while the Isle of Demons gained a measure of authenticity through the story of Marguerite de La Rocque.

In 1542, Marguerite de La Rocque embarked on a voyage to New France (now French Canada) with Jean-François de La Rocque, who was variously described as her husband, uncle, or cousin. During the journey, she became pregnant by one of the sailors. Along with her lady-in-waiting, she was abandoned on an island, which would later be identified as the Isle of Demons. Tragically, her lover, servant, and child died, and for the next two years, Marguerite wandered the island, relentlessly tormented by the demons said to inhabit it. Eventually, Basque fishermen rescued her and brought her back to Europe, where she met Queen Marguerite de Navarre. The queen was so taken with her tale that she turned it into a popular romance.

Between the truth of what actually transpired and Queen Marguerite’s romanticized version, the details became distorted and embellished. Were the demons merely a product of La Rocque’s imagination, or were they Native Americans, a mix of both, or perhaps a later addition to align with the island's ominous name? The island itself certainly existed, and its proximity to the legendary Isle of Demons allowed them to merge into one and the same.

4. Hy Brasil

Hy Brasil, a mystical island off Ireland’s coast, was enveloped in thick mists, only visible for one day every seven years. It shared many similarities with Saint Brendan’s Isle and Antillia, as beneath the fog, it was a land of constant sunshine and prosperity for its inhabitants. The island first appeared on portolan charts in the early 14th century. In 1498, John Cabot embarked on an expedition to find it, though he was unsuccessful. However, throughout the 17th century, there were still reports from people who claimed to have visited it. In 1674, John Nisbet, returning to Ireland from France, encountered dense fog that forced him to anchor off an island. Four sailors went ashore, and after meeting an elderly man who was overjoyed by their company, they were rewarded with several sacks of gold.

Two leading cartographers of the late Renaissance, Abraham Ortelius and Gerhard Mercator, included Hy Brasil on their maps of Ireland. Given that they were relying on available knowledge, they included the island as many earlier reports and maps had suggested its existence. By the 18th century, however, the island had largely vanished from maps, although sailors occasionally continued to claim to have visited it.

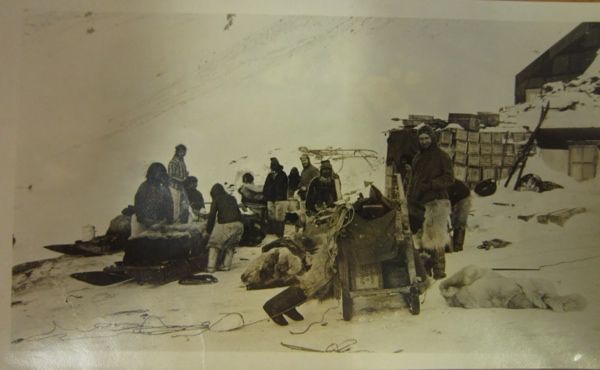

3. Crocker Land

Is a phantom island worth dying for? In 1906, Robert Peary reported sighting a large landmass off Ellesmere Island in the Arctic, which he named Crocker Land after one of his financial backers. While some accused Peary of fabricating the discovery, it’s also possible he saw a Fata Morgana, a type of mirage. This should not be confused with the Croker Hills, another mirage observed by Arctic explorer John Ross in 1816, which he named after the Secretary of the Admiralty. Those hills, too, turned out to be a mirage.

In 1913, Donald Baxter MacMillan led an expedition from the American Museum of Natural History to locate Crocker Land. Filled with excitement over the potential discovery of new plant and animal species, even a new race of people, the team quickly faced unexpected hardships. Frostbite and illness forced many to retreat to the base camp. To make matters worse, the Inuit people, who were familiar with the area, insisted that no such landmass existed. As the situation grew dire, MacMillan dispatched engineer Fitzhugh Green and Inuit guide Piugaattoq to scout the land. At one point, Green shot and killed Piugaattoq, claiming he thought the guide was attempting to escape with the dog team. However, the rest of the expedition members later corroborated a fabricated story that Piugaattoq had fallen into a crevice. Though the expedition was a failure, the photographic records of the Inuit people remained its only notable achievement. The team would be stranded in the Arctic for the next four years.

2. Emerald and Nimrod Islands

By the late 18th century, exploration had shifted focus from the North Atlantic to the South Pacific. While sailors romanticized Tahiti as a paradise, they also sought islands that could provide practical resources, such as timber, minerals, or a suitable stopover for ships traveling between South America and Australia. By this time, the challenge of recording longitude had been solved, and accurate coordinates could now be recorded in ship logs. If a captain claimed to have discovered a previously uncharted, sizable island, it was taken seriously, and expeditions were sent out to investigate. Emerald Island, named after the ship captained by William Eliot in 1821, was one such island. Eliot claimed to have sighted it on his voyage.

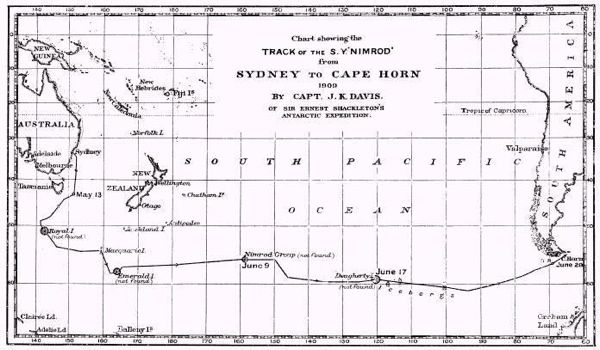

The chart above displays the 1909 expedition route of Captain John King Davis aboard the Nimrod, the same ship used by Ernest Shackleton in his Antarctic exploration. The phantom Nimrod Islands were named after a previous ship of the same name, which had sighted the islands in 1828. Notice the ship’s journey along the locations where the Emerald, Dougherty, and Nimrod Islands were believed to exist. Although Antarctica barely appears on the chart, the ship was in a region that experienced its harshest weather, and icebergs posed significant challenges. It is likely that Eliot and the earlier Nimrod crew had seen a Fata Morgana, a mirage common in the polar regions that distorts distant objects, making them appear as landforms. By the 1940s, the Emerald and Nimrod Islands were officially recognized as phantom islands, though they still appeared on some maps until that time.

1. Phélypeaux and Pontchartrain islands

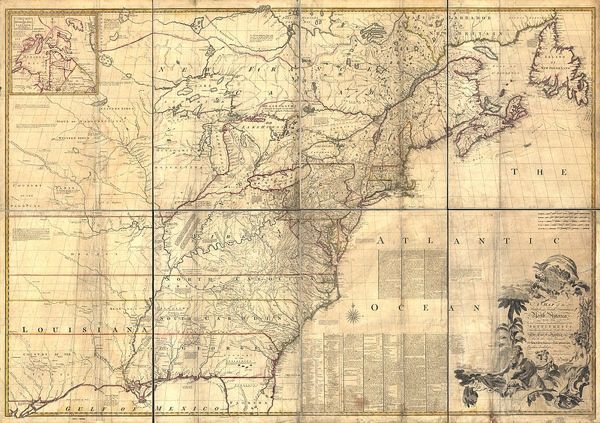

In 1783, Lake Superior was largely understood to be a vast body of water straddling the border between the United States and Canada, a crucial point in the negotiations for the Paris Treaty between America and Britain. The idea that two large islands existed in the center of the lake seemed plausible, especially since they appeared on otherwise accurate maps that were part of the treaty discussions. Furthermore, the boundary running north of these islands matched the one proposed on land. This led to the allocation of the two islands to the United States, with the task of finding them now up for grabs.

Named in the 1720s after Louis Phélypeaux, Comte de Pontchartrain, who served as French Secretary of the Navy, the islands were thought to flatter the Count by appearing on official maps. French officers likely believed that by adding these islands, they would earn the Count’s favor, ensuring continued funding for exploration. Unfortunately for Phélypeaux, he passed away in 1720, before discovering that the islands were entirely fictional. By the 1820s, their non-existence was definitively established, but by then, America had already secured the Louisiana Purchase, and the loss of two imaginary islands was of little concern.