The 'mad scientist' trope was famously introduced by Mary Shelley in her novel Frankenstein. The narrative follows a physician whose fixation on his experiments drives him to disregard both logic and morality in pursuit of his goals.

In reality, similar scenarios have occurred, though on a smaller scale. Researchers have conducted experiments or voiced ideas that push the boundaries of legality and ethics, sometimes crossing them entirely. This behavior earns them the 'mad scientist' title. While Nikola Tesla is perhaps the most well-known example, he is far from the only one.

10. Robert Cornish

Dr. Robert Cornish was a prodigy, graduating from Berkeley at 18 and earning his doctorate by 22. Had he focused his intellect on a different field, he might have made groundbreaking positive contributions. Instead, his career was consumed by an obsession with reanimating the dead.

His position at Berkeley allowed him to return as a researcher and continue his studies with minimal interruptions during the 1930s. Cornish theorized that a body with limited organ damage could be revived using a seesaw-like device to stimulate blood flow, aided by a significant amount of anticoagulants.

Surprisingly, Cornish managed to revive two dogs using his method. His achievements even inspired a 1935 film in which he made a brief appearance.

His ultimate goal, however, was human reanimation. The biggest hurdle was securing a suitable subject. For years, he lobbied prisons to allow him access to recently executed inmates. In 1948, Cornish found a volunteer in Thomas McMonigle, a convicted child murderer, who agreed to undergo the “Cornish teeter” procedure post-execution, with San Quentin’s approval.

Despite his efforts, Cornish faced an insurmountable issue: he required the body immediately after execution, but regulations mandated that the body remain in San Quentin’s custody for several hours before release. As a result, Cornish never achieved his goal of human reanimation.

9. Alexander Bogdanov

Alexander Bogdanov was a scientist who devoted much of his career to an ambitious quest—eternal youth. Unlike Cornish, Bogdanov achieved success in various fields. He was a revolutionary, a key figure in the Bolshevik movement, and a renowned science fiction author. His political achievements even positioned him as a rival to Lenin. After losing political favor, Bogdanov shifted his focus to medical research.

He specialized in blood studies, leveraging his influence to establish the Institute of Blood Transfusion in 1926. Over time, he became convinced that blood transfusions could reverse aging, potentially leading to extended lifespans or even immortality.

Bogdanov experimented on himself, undergoing multiple blood transfusions. He documented the effects, asserting that the treatments halted his hair loss and enhanced his vision.

Bogdanov believed blood transfusions would prolong his life, but ironically, they had the opposite effect. In 1928, he died from a hemolytic transfusion reaction after accidentally receiving blood from a malaria patient.

8. Giles Brindley

Giles Brindley was undoubtedly an eccentric scientist, if not outright 'mad.' Renowned for his research on erectile dysfunction, he pioneered the use of pharmaceutical drugs to induce erections. However, he is best remembered for a notorious presentation at the 1983 Urodynamics Society Meeting in Las Vegas.

During the event, Dr. Brindley discussed his breakthrough in treating erectile dysfunction with papaverine injections. This marked the first time an effective treatment for the condition was presented. However, the audience will never forget how Dr. Brindley demonstrated the success of his treatment—by showcasing its effects on himself.

During his presentation, he displayed images of his erect penis but admitted that the slides alone couldn’t eliminate the possibility of arousal. To prove his point, he nonchalantly lowered his pants and underwear, revealing his erect penis to a shocked audience.

Before the lecture, he had injected himself with papaverine to demonstrate that the treatment could produce erections without sexual stimulation (unless he had an unusual interest in medical talks). Brindley went further, stepping down from the podium and moving through the front row, flaunting his erection to emphasize his findings.

7. Paracelsus

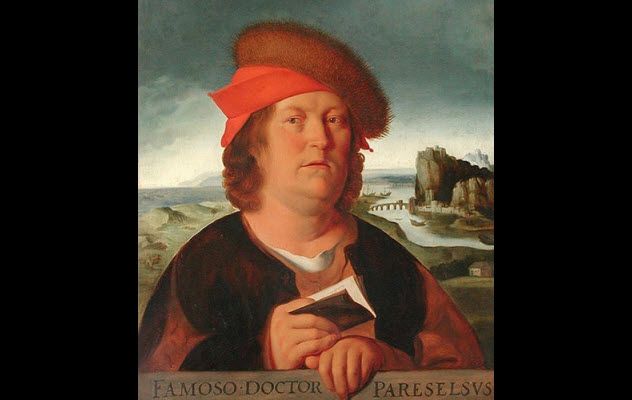

Paracelsus, a 16th-century Swiss-German scientist, made significant contributions to medicine, biology, and chemistry. He is often credited as the father of toxicology for his groundbreaking idea that small amounts of toxic substances could have medicinal benefits. His belief that 'the dose makes the poison' and his use of inorganic compounds for treatment frequently clashed with the prevailing medical views of his time.

While ahead of his time, Paracelsus also explored alchemy and the occult. In 1537, four years before his death, he authored De Rerum Naturae, a work addressed to his brother, revealing alchemical secrets he had uncovered. Among these was a method for creating a homunculus, a miniature human crafted through alchemical processes.

The process involved placing sperm in venter equinus (horse manure) to decay for about 40 days, after which it would take on a life-like form, resembling a tiny, translucent humanoid without a body. This creation was then nourished daily with human blood while remaining in the manure. After 40 weeks, the homunculus would be fully formed.

6. Wendell Johnson

Wendell Johnson, a psychologist at the University of Iowa, gained infamy for a 1939 experiment later dubbed the “monster study.” Johnson, who researched speech therapy, believed stuttering was a learned behavior, drawing from his own childhood experiences. He was convinced it could be unlearned with the right methods.

To explore this, Johnson and graduate student Mary Tudor conducted an experiment involving 22 orphans. They divided the children into two groups of 11, with each group containing both stutterers and fluent speakers.

One group received positive reinforcement during speech therapy. Stutterers were assured their speech was fine, while fluent speakers were given the same feedback as a control measure.

The other group endured six months of negative reinforcement and criticism to observe its impact on stuttering. The most affected were six fluent speakers in this group, who were included to test if such methods could induce stuttering. Tragically, many of these children developed lifelong speech issues.

When Johnson’s colleagues learned of the experiment, they discreetly suppressed it. However, in 2001, the study came to light. Six former participants sued the university for psychological trauma and were awarded nearly $1 million in damages.

5. Robert Knox

In the early 1800s, Robert Knox was one of England’s most esteemed doctors. A trailblazer in comparative anatomy, he taught at the country’s largest anatomical school. At his peak, Knox delivered lectures to audiences of 500 students.

Eventually, Knox encountered a shortage of cadavers. In a decision that would forever stain his career, he partnered with two men named Burke and Hare, who provided him with fresh corpses obtained through murder. Although Burke and Hare were eventually caught, their 1828 killing spree—resulting in 16 deaths—remains one of Britain’s most notorious crimes.

All 16 bodies ended up with Knox. Officially, he was cleared of involvement in the murders, as the medical community at the time accepted an “ask no questions” approach to sourcing cadavers. However, critics argued that a skilled surgeon should have noticed signs of foul play and questioned how Burke and Hare supplied so many bodies in just 10 months.

Regardless of his actual knowledge, Knox’s reputation suffered greatly, as many believed he turned a blind eye to the murders. On a positive note, the public outrage led to the Anatomy Act of 1832, which reformed the sourcing of cadavers for medical research.

4. Andrew Ure

In the late 18th century, galvanization became a scientific obsession. Luigi Galvani demonstrated that electrical currents could stimulate animal muscles, even in dead specimens. His experiments with twitching frog legs captivated the public, but they soon demanded more dramatic demonstrations.

The focus eventually shifted to human subjects. Giovanni Aldini, Galvani’s nephew, gained fame for electrifying the corpse of executed murderer George Foster, causing it to move. However, Scottish physician Andrew Ure took these experiments to an even more extreme level.

Ure acquired the body of Matthew Clydesdale, another executed criminal, and theorized that galvanization might revive the dead. He inserted rods into various parts of Clydesdale’s body, inducing violent convulsions. By stimulating the supraorbital nerve, Ure made the corpse’s face twist into grotesque expressions, terrifying witnesses to the point of fainting or fleeing.

Unsurprisingly, Ure failed to resurrect Clydesdale. He blamed the failure on the body being devoid of blood, which prevented the heart from restarting despite the electrical stimulation.

3. Johann Conrad Dippel

Several scientists are believed to have inspired Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. While Andrew Ure and Giovanni Aldini are often cited, Johann Conrad Dippel stands out because he was actually born at Castle Frankenstein.

Dippel, a 17th-century theologian and physician, had a tumultuous relationship with religion, frequently altering his beliefs to fit his situation. His radical ideas sometimes provoked violent mobs seeking his life, further aligning him with the Frankenstein narrative.

True to his 'mad scientist' image, Dippel experimented with alchemy. His work coincided with the rise of iatrochemistry, a branch of alchemy focused on using chemical solutions to treat diseases. Alchemists of the time were obsessed with discovering a universal cure.

One of his creations was 'Dippel’s oil,' a pungent substance derived from the destructive distillation of animal bones. Dippel touted it as a remedy for various ailments.

Dippel’s experiments and notoriety fueled numerous rumors. The foul odors from his lab led people to believe he was working with corpses, attempting soul transfers or resurrection. He is arguably the closest real-world counterpart to Frankenstein. Whether Mary Shelley knew of him remains a mystery.

2. Lytle Adams

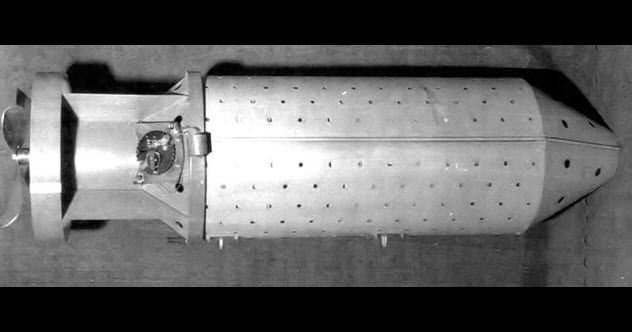

Warfare often sparks creativity, and during World War II, the U.S. devised an unconventional strategy known as “Project X-Ray.” This plan involved using bats as weapons.

The concept was to load hibernating bats with napalm into bombshells and drop them over Japan. Upon release, the bats would awaken and disperse, causing widespread destruction. Despite being passed between departments, the project was ultimately abandoned, and the bat bombs were never used.

The idea originated with Dr. Lytle Adams, a Pennsylvania dentist. Inspired by witnessing millions of bats emerging from Carlsbad Caverns in New Mexico, he envisioned using them to deliver explosives and wreak havoc on enemy cities.

Typically, such an outlandish proposal would be dismissed. However, Adams had a connection to Eleanor Roosevelt, which helped his case. His plan was reviewed by the National Research Defense Committee, which deemed it feasible. A presidential memo even stated: “This man is not a nut.”

1. Carney Landis

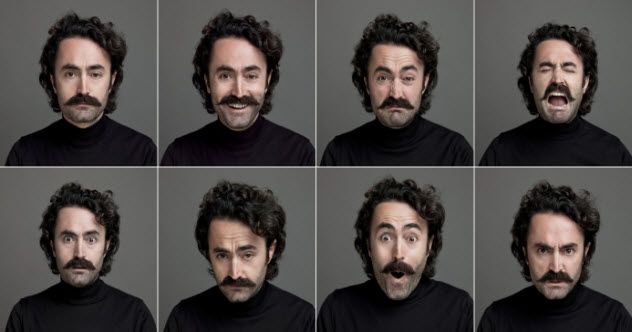

Carney Landis could be considered a “mad scientist in training” as he was a psychology student at the University of Minnesota in 1924 when he conducted a strange experiment on his peers. Landis theorized that all humans share the same facial expressions to express emotions, such as anger, fear, and happiness. To test this, he recruited volunteers, marked their faces to monitor muscle movements, and exposed them to various stimuli to evoke emotional reactions.

To ensure strong responses, Landis subjected participants to extreme tasks, such as smelling ammonia, viewing pornography, and placing their hands in buckets filled with slimy frogs. The experiment culminated in participants being asked to decapitate a live rat while Landis photographed their reactions. While most hesitated, two-thirds complied. Those who refused had Landis perform the act for them. Shockingly, a 13-year-old boy was also included in the experiment.

Although Landis’s hypothesis was incorrect, his experiment paralleled the famous Milgram obedience study conducted decades later. Landis, however, failed to explore the broader implications of his findings.