Centuries ago, small private museums called cabinets of curiosities became popular among royalty, nobility, and affluent members of the middle class who could afford to curate them. With travel being rare and limited, many natural objects, plants, and animals appeared extraordinarily rare and fascinating.

These cabinets showcased extraordinary natural wonders, featuring peculiar specimens and breathtaking artifacts from far-off regions. Beyond being mere curiosities for the wealthy, they served as educational tools, helping people explore and comprehend the enigmatic world they lived in.

10. Kunshtkameroy

In 1714, Tsar Peter the Great of Russia (1672–1725) founded the Kunshtkameroy (“cabinet of rarities”) in Moscow, later relocating it to St. Petersburg’s Summer Palace. He instructed travelers to bring back anything “exceptionally ancient or unusual” from their expeditions.

His collection included items like “bones, stones, ancient tools, and weaponry,” alongside “medicines from Dutch anatomist Ruysch’s collection, small creatures and birds, herbariums, butterflies, seashells, and more.”

The cabinet also featured peculiar exhibits: “children’s heads preserved in alcohol, embalmed body parts,” and human “monsters”—individuals with “unique anatomical traits.” Over time, Peter’s collection grew to include “ancient pagan artifacts, everyday tools and garments, idols, rare coins, manuscripts, mineral samples, and much more.”

9. Royal Danish Kunstkammer

King Frederick III of Denmark (1609–1670) curated his own cabinet of curiosities, the Royal Danish Kunstkammer (“wonder room”), located at Copenhagen Castle. Also referred to as the Museum Regium, it was housed in a dedicated six-room structure built in 1665.

One room displayed “naturalia,” such as a hip bone discovered by Frederick’s physician, Dr. Sperling, near Bruges in Flanders. Initially mistaken for a “giant’s” remains, it was later identified as part of an elephant’s skeleton. The collection also included additional elephant bones and two sets of partial teeth.

The teeth were exhibited alongside oddities like horns reportedly grown from Frederick’s horse’s ears, a white sparrow, and a “small dragon, crafted with great skill.” Other exhibits featured five elephants, various elephant parts, and “a preserved ox and walrus.”

Following the death of Ole Worm, another avid collector, Frederick acquired his cabinet, further enriching his own assortment of rare and fascinating items.

8. Kunst- und Wunderkammer

Rudolf II (1552–1612), Holy Roman Emperor, amassed an impressive array of art, ancient relics, and exotic wonders in his Kunstkammer (“art room”) and Wunderkammer (“wonder room”). While these collections no longer exist in their original form, the artifacts looted by Swedish troops during the 1648 siege of Prague reveal the immense scale of Rudolf’s treasures, which once occupied multiple rooms in his castle.

The looted treasures included countless paintings, bronze sculptures, coins, medals, “agate and crystal vessels, faience artworks, Indian curiosities, gemstone creations, uncut diamonds, mathematical tools, and numerous other items.” Similar to other cabinets, Rudolf’s collection aimed to encapsulate the marvels of nature, offering viewers a curated glimpse into the beauty, awe, and mystery of the world.

7. The Studiolo of Francesco I de’ Medici

Francesco I de’ Medici (1541–1587), Grand Duke of Tuscany, was an ardent enthusiast of both art and science. His cabinet, housed in the vaulted chamber of Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio, contained “his mirabilia, rare and exquisite objects gathered from across the globe.”

Francesco would retreat to this private space to examine his treasures, which were housed in “20 cabinets arranged across four walls.” Each wall’s theme was inspired by a corresponding painting. After his death, the studiolo was disassembled, but the collection has since been reconstructed, albeit not in its original configuration.

To maintain secrecy, the entrances to his studiolo were concealed behind cabinet doors. Francesco is depicted in two of the room’s paintings, possibly symbolizing his identity as a connoisseur of art and nature’s finest creations.

6. Chamber of Art and Curiosities

Ferdinand II, Archduke of Austria (1529–1595), established the Chamber of Art and Curiosities at Ambras Castle in Innsbruck, where it remains exhibited to this day. A gouache painting, sent by his Spanish ambassador, served as an early form of advertisement, showcasing items for sale. The archduke acquired them all, enriching his “encyclopedic” collection with a rhinoceros horn, tooth, and skin, as well as a “covered goblet” crafted from the animal’s horn.

Ferdinand’s assortment also featured “coral arrangements in cabinet boxes, intricately turned wood and ivory pieces, glass figurines, porcelain and silk artworks, hand stones, bronze animal sculptures, scientific instruments, automatons, and clocks.” His gallery of “curious individuals” even included a portrait of Count Dracula.

5. Kircherianum

As a mathematics professor at Collegio Romano, Jesuit priest Athanasius Kircher (1602–1680) pursued his fascination with rare and exotic natural wonders by creating the Kircherianum, a cabinet of curiosities. When his collection outgrew his living space, he relocated it to a larger area, proudly declaring that no visitor could truly say they had experienced Rome without seeing his cabinet.

European nobility flocked to the Kircherianum, a collection so extensive that cataloging it took decades. Kircher, a man of boundless imagination, theorized that certain animals might be hybrids. He speculated that the giraffe was a blend of a camel and a leopard, while the armadillo in his collection might have been the offspring of a turtle and a hedgehog or porcupine.

4. Belsazar Hacquet’s Cabinet

As historian R.J.W. Evans noted, cabinets of curiosities fell into two categories: “princely” collections curated by royalty and nobility, and more modest ones owned by scholars and private individuals.

Despite financial constraints, Carniolan surgeon Belsazar Hacquet (1739–1815) amassed a remarkable collection of 4,000 curiosities. His carefully selected items included “specimens of Carniolan and exotic plants, a smaller assortment of animal specimens, a library dedicated to natural history and medicine, and an anatomical theater.”

3. P.T. Barnum’s Collection

Americans shared Europe’s fascination with curiosities, and showman P.T. Barnum (1810–1891) masterfully exploited their allure. By assembling a diverse array of oddities, Barnum enhanced his displays with “live curiosities,” including “industrious fleas, a hippo he marketed as ‘The Great Behemoth of the Scriptures,’ and various bearded ladies.”

His creation became a blend of museum and circus, captivating the public. Many of these artifacts found their way to Barnum’s American Museum in New York City, which, according to Barnum, attracted 15,000 visitors daily.

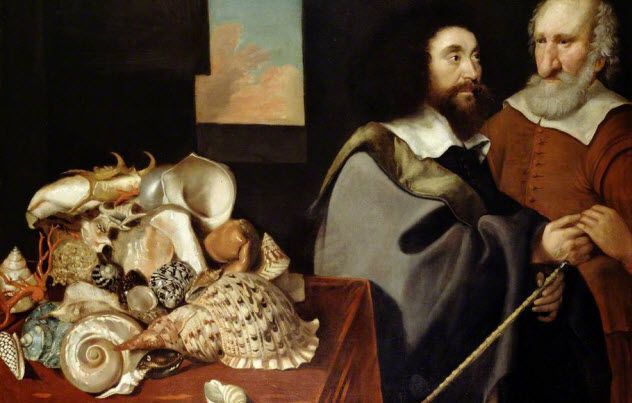

2. ‘The Ark’ of John Tradescant the Elder

John Tradescant the Elder (circa 1570s–1638), a botanist, gardener, and entrepreneur, curated a cabinet of curiosities that attracted paying visitors, including royalty and nobility. The experience was evidently worth the admission fee, given its prestigious audience.

His travels allowed him and his son to gather rare plants and artifacts, such as “carvings on fruit stones” and “drawings of creatures from a papal menagerie.” The fruit-stone carvings showcased detailed scenes of musicians, animals, and religious imagery, including a depiction of the Crucifixion.

With help from collaborators, Tradescant amassed such a diverse array of oddities that his collection earned the nickname “The Ark.” He bequeathed it to his son, but after Tradescant the Younger’s death, the cabinet passed to neighbor Elias Ashmore. Hester, the Younger’s widow, accused Ashmore of theft and tragically “was found dead, facedown in a shallow pond on her property.”

1. Museum Wormianum

Danish physician Ole Worm (1588–1654) curated a room-sized cabinet of curiosities in his residence. Combining natural specimens, scientific artifacts, and cultural items, it was designed to astonish visitors while also encouraging “learning and comprehension.”

A 1665 engraving of his Museum Wormianum reveals some of the captivating objects he exhibited. Fish and bird skeletons dangle from the ceiling, while antlers and horns embellish one wall. Stuffed armadillos, massive turtle shells, crocodiles, and lizards adorn the opposite wall. Shelves display stuffed birds, an ostrich egg, a human skeleton, skulls, and various rocks and minerals.

Worm’s collection also included his pet auk (now extinct), a lemur, and a deer. Today, a reconstructed version of his cabinet is a permanent exhibit at the Geological Museum within Denmark’s Natural History Museum.