Scientific advancement thrives on a combination of theoretical exploration and practical experimentation. When human participation is necessary for a study, researchers generally have two primary approaches. The most common method is to seek out volunteers, often incentivized by monetary compensation rather than a passion for scientific progress. Alternatively, the researcher may choose to become the subject of their own experiment. Below are ten extraordinary examples of self-experiments that range from bizarre to perilous to groundbreaking.

10. Pain

Quantifying pain is a complex challenge. While some individuals endure severe injuries without complaint, others may react intensely to minor wounds. To establish a pain scale, one approach is for an individual to undergo various painful experiences and compare their intensity. This is precisely what Justin Schmidt did to evaluate the pain inflicted by different invertebrate stings. Schmidt's pain scale ranges from 0 (harmless to humans) to 4 (agonizing). For the most severe stings, he includes vivid descriptions to convey the full extent of the suffering. For instance, the sting of the Pepsis wasp was described as causing 'instant, unbearable pain that completely incapacitates the victim, leaving them capable of little more than screaming.'

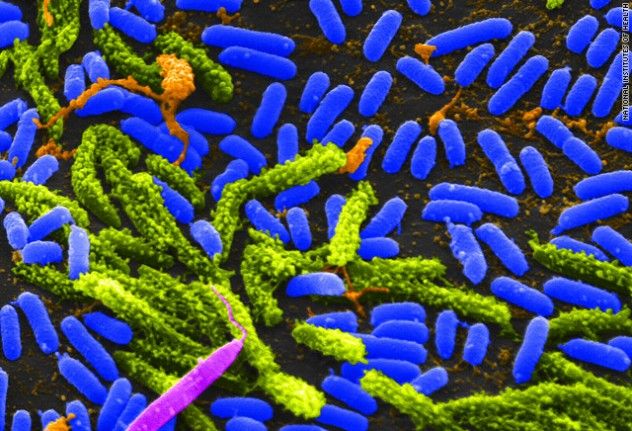

9. Cholera

Max von Pettenkofer, a towering figure in 19th-century German medicine, is often regarded as the pioneer of modern hygiene. During his time, cholera was a devastating disease, notorious for causing fatal dehydration through severe diarrhea. Today, we understand that cholera is caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae, transmitted through fecal contamination. Pettenkofer, living during the nascent stages of germ theory, believed cholera resulted from a combination of germs and specific soil conditions that created an infectious miasma. To demonstrate the role of soil in cholera development, he boldly consumed a sample of cholera bacteria. Although he experienced mild discomfort, he did not suffer the fatal symptoms of extreme vomiting and diarrhea. This experiment highlights the limitations of self-experimentation, as a single case cannot conclusively validate a theory.

8. Food

Since the dawn of humanity, it has been evident that food is essential for survival. However, the processes occurring inside the body after consumption and the discrepancy between intake and excretion remain less clear. In the early 1600s, a physician named Sanctorius embarked on a meticulous 30-year experiment, weighing everything he consumed, his own body, and all excretions. He designed a specialized chair to track weight changes accurately. His findings revealed that for every 8 pounds of food ingested, only 3 pounds were excreted as waste. He attributed the difference to an unexplained process he termed 'insensible perspiration.' Such dedication to weighing bodily waste for decades exemplifies scientific commitment, though using one's own waste is arguably preferable to others'.

7. Infectiousness

Yellow fever, a mosquito-borne viral disease, continues to claim 30,000 lives annually despite the availability of an effective vaccine. Historically, epidemics ravaged North America, prompting people to flee cities during 'fever season.' Intrigued by the disease's nature, a young medical student named Stubbins Ffirth sought to prove it was non-contagious. Using samples from infected patients, he attempted to contract the disease himself. He consumed vomit, applied it to open wounds, and even poured it into his eyes. Despite these extreme measures, he remained unaffected. He repeated the experiments with blood, saliva, and pus, concluding yellow fever was not infectious. Unbeknownst to him, his samples were from patients past the contagious phase, rendering his efforts futile. Yellow fever is indeed transmissible, and Ffirth never realized his sacrifices were in vain.

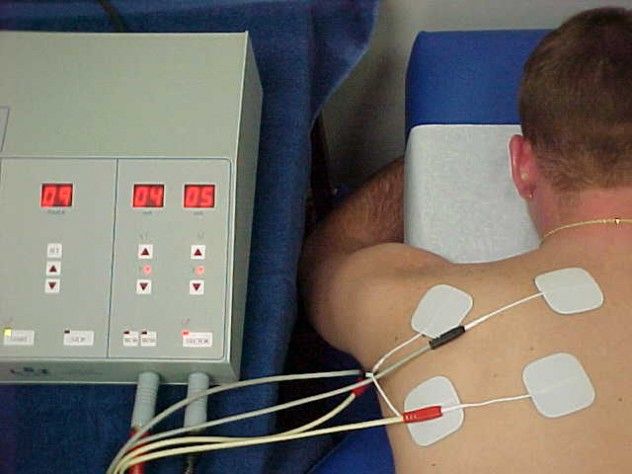

6. Electrical Stimulation

The advent of electricity and its impact on deceased creatures spurred a wave of scientific inquiry into its role in living organisms. Johann Wilhelm Ritter, renowned for discovering ultraviolet light, was among these pioneers. Moving beyond experiments on corpses, he tested electrical currents on his own body, documenting the effects. His most striking discovery occurred when he applied a Voltaic pile to his genitals, inducing an orgasm. Fascinated, he repeated the experiment obsessively, even jesting about marrying his Voltaic pile. The escalating intensity of his self-administered shocks often necessitated morphine for pain relief, likely contributing to a shortened lifespan.

5. Surviving Submarines

Warfare has historically served as a fertile ground for scientific discovery. The abundance of casualties allowed early medical practitioners to delve into human anatomy. However, the desire to save lives also drove some scientists to undertake perilous experiments. J. B. S. Haldane, a prominent evolutionary theorist, was known for his bold approach. Influenced by his biologist father, who experimented on him as a child, Haldane investigated the effects of rapid pressure changes experienced by submariners escaping wrecks. He subjected himself repeatedly to decompression chambers, gaining insights into nitrogen narcosis and decompression sickness. Despite suffering seizures and ruptured eardrums, he remained unfazed, quipping, 'The drum usually heals; if a hole remains, one can blow tobacco smoke from the ear, a unique social skill.'

4. Upside Down World

Our understanding of the world is shaped by our senses, prompting scientists to explore how these senses function. George Stratton conducted an experiment to study how the brain adapts to altered visual perception. By wearing special glasses, he inverted his vision, making up appear down and down appear up. Initially, the disorientation caused nausea and a sense of detachment. However, within days, he adapted and could perform daily tasks normally. Over time, he even perceived the inverted images as correctly oriented. Upon removing the glasses, the world seemed upside down to him. While subsequent experiments haven't replicated his sense of normalcy, they highlight the brain's remarkable ability to adjust to perceptual changes.

3. Stomach Ulcers

Breaking the fundamental lab rule of no eating or drinking can sometimes yield groundbreaking discoveries. Stomach ulcers, often joked about as stress-related, were once a leading cause of death due to bleeding or perforation risks. The mystery of their cause was unraveled by Barry Marshall and Robin Warren, who identified the bacterium Helicobacter pylori in patients' stomachs. To prove their theory, Marshall ingested a culture of H. pylori, developing gastritis and ulcer symptoms. This bold experiment confirmed the bacterium's role and led to effective antibiotic treatments. Their work earned them the Nobel Prize in 2005.

2. Heart Catheter

Accessing the heart for diagnosis or treatment is a delicate process. While opening the chest was once nearly fatal, Werner Forssman pioneered a safer method in the 1930s. Studying cadavers, he theorized that a thin tube, or catheter, could be guided through blood vessels to the heart. To test this, he performed the procedure on himself, threading the catheter into his heart. Despite the risk of fatal vessel damage, he successfully walked to an x-ray machine to confirm the catheter's placement. His daring experiment earned him a share of the 1956 Nobel Prize in Medicine.

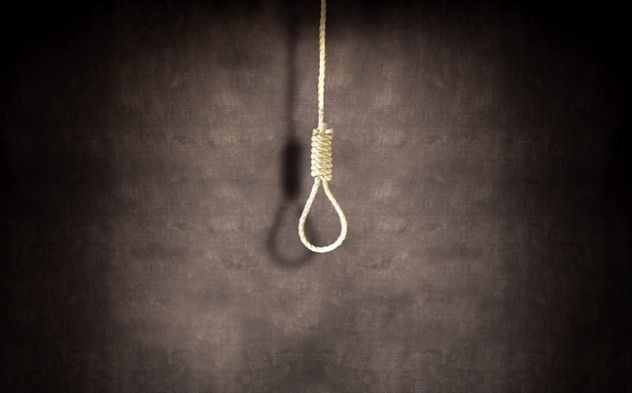

1. Hanging Sensation

Nicolae Minovici was driven by a singular question: what does it feel like to be hanged? While most would settle for the assumption that it’s 'probably unpleasant,' Minovici sought definitive answers. To satisfy his curiosity, he subjected himself to hanging multiple times, using various types of nooses. With the help of assistants, he was lifted into the air, enduring excruciating pain that lingered for weeks after each trial. Unlike condemned individuals, whose suffering ends quickly, Minovici’s prolonged agony provided no insight into the experience of those who undergo the 'long drop' and a broken neck during execution.