Few events in history have been as cruel and impactful as the Nazi Holocaust, yet amidst the devastation, there were moments of courage, perseverance, and humanity’s unyielding will to endure. It is uplifting to remember that one of humanity’s greatest qualities—love—can thrive, even in the darkest times.

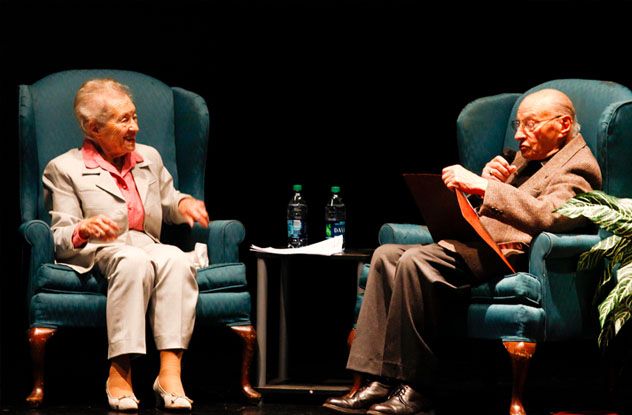

10. Jerzy Bielecki and Cyla Cybulska

In 1943, Cyla Cybulska was sent to Auschwitz with her parents and siblings. She was the sole survivor of her family, and her life was spared thanks to a man named Jerzy Bielecki. By the time Cyla arrived at the camp, Jerzy had already been imprisoned for three years. A Roman Catholic, he had been captured for aiding the Polish resistance, while Cyla, a Jew, was among those brought to the camp.

Jerzy first saw Cyla while he was working in a grain silo. She had been assigned the task of repairing sacks. Reflecting on that moment in 2010, he recalled, 'It seemed to me that one of them, a pretty dark-haired one, winked at me.' They exchanged a few words when they could, and soon they were deeply in love. Jerzy made it his mission to find a way to rescue her.

Jerzy spent eight months piecing together a guard’s uniform from stolen fabric. He swiped a pass and forged documents to have a prisoner, Cyla, sent to work at a nearby farm. On July 21, 1944, he quietly took her from her barracks, and together they walked out of the camp. They did not stop for 10 days, traveling until they reached a relative's home. Jerzy rejoined the Polish resistance and used his connections to find a hiding place for Cyla. He went off to fight, unaware that he wouldn’t see her again for nearly forty years.

For years, both Cyla and Jerzy believed the other had perished. Cyla eventually moved to Brooklyn, married, and started a family, while Jerzy did the same in Poland. In 1983, Cyla shared her story with her housekeeper, who recognized the tale, saying, 'I saw a man telling the story on Polish television. He’s alive.'

Cyla tracked down Jerzy’s phone number and they reunited a few weeks later. When she arrived at Krakow’s airport, Jerzy greeted her with 39 roses, each symbolizing a year since they had last seen each other. They developed a strong friendship, meeting 15 more times over the years despite living on different continents, until Cyla passed away in 2005.

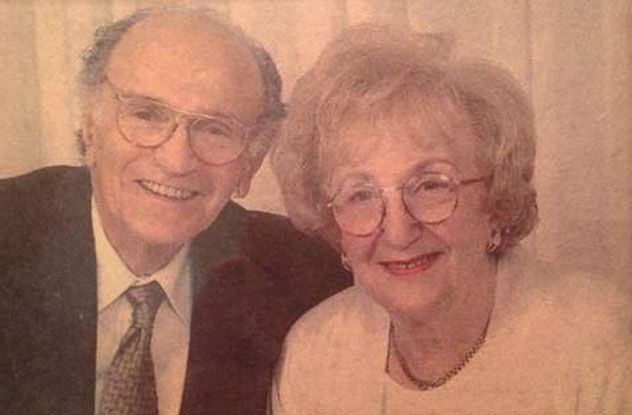

9. Manya and Meyer Korenblit

The story of Manya and Meyer Korenblit has been described by their son as one of miracles. They were two Jewish teenagers in love when the Nazis began rounding up people in their hometown of Hrubieszow, Poland. Initially, they were confined to ghettos, but later, they were transported to a concentration camp. By the end of the war, 98 percent of the town’s Jewish population had been murdered by the Nazis.

The couple ended up in the same camp, Budzyn. Meyer would sneak to the fence separating the men’s and women’s sections to speak with Manya, and it was there that they made a promise to each other. If they both survived the war, they would return to their hometown and wait for one another. Shortly after, they were separated and spent the next three years in 11 different camps.

When they were freed, their combined weight was just 64 kilograms (143 lb), less than the average weight of a single adult in Europe today. Meyer had escaped a death march from the Dachau concentration camp and found refuge on a farm until he was discovered by American forces. Manya was the first to return to Hrubieszow. She waited six weeks, uncertain of Meyer’s fate—but he eventually made it back to her.

8. John Rothschild Saves His Fiancée

Swiss Jew John Rothschild met his future wife, Renee, in 1939. Renee was German and had been living in France since the Nazis came to power in 1933. When the city of Strasbourg was evacuated by the French authorities in preparation for the Nazi invasion, Renee had to leave her home. She knew John’s family, and they invited her to stay with them at their farm in the French town of Saumur. The two, both 19 years old, fell in love, and within three weeks, they were engaged.

Their lives took a tragic turn in the following years. John returned to Switzerland to fulfill his national service, while Renee found work elsewhere in France. In July 1942, John's entire family in Saumur was deported to Auschwitz. The next month, Renee was detained at the Drancy internment camp, where she was eventually sent to Auschwitz as well.

John saw only one way to save her. He left the safety of Switzerland and became one of the rare Jews to deliberately enter a Nazi prison camp. He brought a gift of cigars for the camp commander, Swiss work papers for Renee, and little else. He later recalled the experience, saying, 'You can imagine the feeling I had when that gate closed behind me. They could have just kept me there.'

After two days, the French camp commander finally agreed to release Renee. It would be another year before the Germans took full control of the camp. With Renee free, the couple now faced the challenge of escaping Nazi territory. They reached a border town, found a guide, and navigated their way to a gap in the barbed wire along the Swiss-French border. Once in Geneva, a hotel clerk, moved by their story, gave them the best suite for the night. The couple married that same year and have been together for over 70 years.

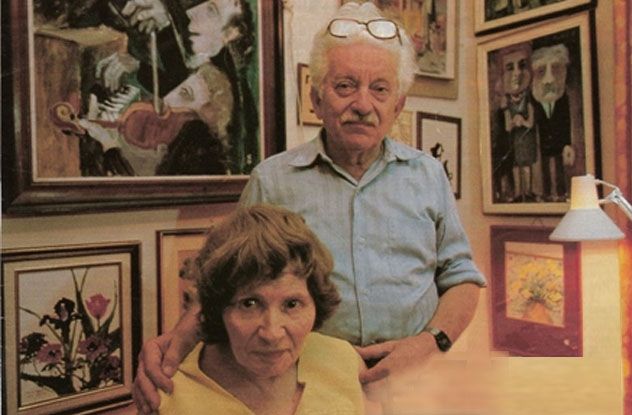

7. David and Perla Szumiraj

David Szumiraj arrived at Auschwitz in late 1942. While working in the potato fields, he found himself near a young woman named Perla. Although speaking was forbidden, they would often exchange meaningful glances when the guards weren’t watching.

The exchanged glances were enough for the two to fall for each other. When they were finally able to speak, David recalled, 'It was already inside us, the idea that we were a couple, that we were going to get married.' Their first conversation ended with their first kiss.

In January 1945, with Soviet forces approaching, the Nazis began evacuating the prisoners. The evacuation from Auschwitz became one of the most notorious death marches in history, claiming the lives of 15,000 people. After a week of surviving on nothing but snow, David’s train was bombed by British planes. Weighing just 38 kilograms (83 lb), he managed to survive by eating grass until American soldiers found him. To this day, he refuses to eat lettuce.

David had no idea where Perla was. He asked a friend to go to a camp in Hamburg that housed many women—and there she was. David found out his friend had succeeded when Perla suddenly jumped out from behind a tree at the army base where David was staying.

They got married, had a daughter, and made the decision to relocate to Argentina to reunite with some of David’s surviving relatives. With $20,000 immigration fees out of their reach, they were smuggled into the country from Paraguay, where they spent the next six decades living happily together.

6. Margrit And Henry “Heinz” Baerman

Before Heinz Baerman passed away in 2013, he and his wife Margrit dedicated much of their time to sharing their Holocaust experiences with younger generations. They spoke to children in schools and museums about the horrors they endured—beatings and starvation at the hands of the Nazis—but also about the love they shared, which helped them survive it all.

They had crossed paths shortly before the war broke out, in Cologne. At one point, Heinz had been reduced to surviving by chewing on bones discarded in a pile of refuse outside the guards’ kitchen at his labor camp. When he eventually reached the fence where Margrit was held, she remarked, “he looked like a skeleton.” She pleaded with the camp commander to allow him entry so she could care for him for a few days. To her astonishment, he agreed. However, they were soon separated.

When Margrit was freed in 1945, she was gravely ill with typhus and weighed just 30 kilograms (68 lb). She credits her love for Heinz with providing her the strength to carry on. Heinz located her by sending a postcard to “The Oldest of the Jews in Neustadt in Holstein,” asking them to find her and urge her to reach out to him.

After marrying, the couple moved to Chicago, where they spent 67 years together until Heinz was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Just three weeks later, he passed away in his wife’s arms.

5. Olga Watkins And Julius Koreny

In 1943, 20-year-old Olga Watkins met Julius Koreny, a Hungarian diplomat, in her hometown of Zagreb, Croatia. Olga later admitted that he was “hardly my type,” but over time, their feelings for each other deepened. They became engaged, but soon after, Julius was arrested by the Nazis and taken to a prison in Budapest.

Olga was determined not to leave Julius behind, so she embarked on a journey of 340 kilometers (211 miles) to find him. Forced to use a false identity, she was briefly imprisoned for two weeks. However, she eventually succeeded in reaching the prison and managed to speak with Julius. Shortly thereafter, he was transferred to Dachau, a notorious concentration camp in Germany.

Olga followed him, traveling another 700 kilometers (440 miles), only to learn that Julius had been relocated further into Nazi-occupied Germany. She reached Ohrdruf just as the Allies were liberating Germany. By the time she learned that Julius had been moved again, the final stretch of her journey became a bit easier. She eventually found him in a hospital at Buchenwald. Julius, in complete disbelief, asked, “Oh God, how did you find me?”

Though they married, their story has a bittersweet twist. In 1948, Julius was at their home in Budapest while Olga traveled to Zagreb to visit family. When the Iron Curtain fell, they were separated by its divide and unable to contact each other. Both remarried, and it wasn’t until the 1980s that they were reunited. Their reunion inspired Olga to write a book about her remarkable journey through war-torn Europe.

4. Howard and Nancy Kleinberg

Bergen-Belsen was one of the most horrific concentration camps imaginable. Thousands of lifeless bodies were stacked around the camp, and the place was infested with typhus, typhoid, and tuberculosis. A severe shortage of food pushed some prisoners to the brink of cannibalism. When the British liberated the camp, more than 38,000 people were held there, though only around 10,000 survived, most having succumbed to the disease.

Howard Klein seemed destined to be one of those who perished. After being forced by guards to dispose of bodies in a mass grave, exhaustion overtook him, and he collapsed among the corpses. “I felt I had to lie down in order to meet my maker,” he recalled. It was then that a young woman named Nancy saw him and realized he was still alive. Although her companions doubted his chances of survival, she insisted they move him to a bunk, giving him a chance to recover.

Howard was too weak to move or even speak. Nancy took care of him for an entire week before he regained the strength to speak. She continued to nurse him for another two weeks, but during that time, Howard vanished while she was away searching for food. The British had moved him to a hospital, and Nancy couldn’t find him. He had been so close to death that it took him another six months to fully recover.

By pure chance, both Howard and Nancy chose Toronto as their destination when they decided to emigrate. When Howard discovered that Nancy was living in the city, he showed up at her doorstep, flowers in hand, with no idea what to say. “How many times can you say ‘Thank you for saving me?’” he recalls. “I was at a loss for words.”

Three years later, the two married, and by 2013, they were still happily together. Howard spent their years together treating his wife “like a princess,” according to Nancy. That’s a pretty good way to express his gratitude.

3. Cyla And Simon Wiesenthal

We’ve mentioned Simon Wiesenthal before. This Austrian Jew not only survived the Holocaust but later dedicated his life to bringing thousands of Nazi war criminals to justice. However, the story of his marriage to Cyla Wiesenthal is just as remarkable as his pursuit of justice.

Cyla and Simon tied the knot in 1936 and settled in the Polish city of Lvov, which is now part of Ukraine. When the Nazis arrived in 1941, they turned Lvov into the Jewish ghetto of Lemberg. That October, the Wiesenthals were deported to a small labor camp, where they worked for a year. By that time, the systematic slaughter of Jews was intensifying, and the couple knew their fate: deportation to a death camp seemed inevitable.

Simon managed to establish connections with the Polish resistance group, Armia Krajowa. He used his position in the camp’s railway shop to gain maps of railway junctions, which he traded for their help in rescuing Cyla. In early 1943, the resistance smuggled her out of the camp and gave her a false Christian identity.

Cyla found shelter in Lublin, a city more than 200 kilometers (120 mi) to the north. In June 1943, the Gestapo began rounding up suspicious women in the area, forcing Cyla to return to Lemberg to reunite with Simon. After hiding for two days in a train station cloakroom, she managed a brief meeting with him. Once again, Simon used his resistance contacts to find her safe haven in Warsaw.

In 1944, Simon attempted to take his own life. Although he survived, the crucial detail of his survival was lost when Armia Krajowa informed Cyla about Simon’s actions, leading her to believe he had died. Meanwhile, Simon was moved to another camp, where he met a man who had lived on the same street in Warsaw as Cyla. The man told Simon that the Nazis had destroyed every building on that street with flamethrowers, leaving no survivors. When Simon’s camp was liberated in May 1945, he contacted the Red Cross, who confirmed his wife’s death.

However, Cyla was not dead. She had been captured in Warsaw and sent to a camp, where the British liberated her a month before the Americans freed Simon. Both Simon and Cyla believed the other was dead until Cyla was reunited with a mutual acquaintance in Krakow. He was astonished to see her and said, “I’ve just had a letter from your husband asking me to help locate your body.” Unfortunately, they still had a problem—Simon was in the American zone, and Cyla was in the Soviet zone.

Simon hired a man named Felix Weissberg to help get Cyla across the border. Unfortunately, Weissberg was anything but reliable. He destroyed Cyla’s papers before reaching Krakow and then forgot her address. He resorted to posting a notice on a bulletin board: “Would Cyla Wiesenthal please get in touch with Felix Weissberg who will take her to her husband in Linz.”

When three women appeared, all claiming to be Cyla, Weissberg had no idea which one was telling the truth. Unable to smuggle three women across the border with new fake documents, he had to make a guess after interviewing each one. Thankfully, he chose correctly. The couple was finally reunited, and they wasted no time making up for their two years apart. Their daughter was born nine months later.

2. Gerda And Kurt Klein

When Gerda Weissmann-Klein was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2010 by Barack Obama, he remarked, “She has taught the world that it is often in our most hopeless moments that we discover the extent of our strength and the depth of our love.” The strength he referred to was her six decades spent as an author and advocate for human rights. The love he spoke of was the moment Gerda met Kurt Klein, the man who would become her lifelong partner.

In January 1945, Gerda was one of 4,000 Jewish women forced to march from slave labor camps by SS guards. They trudged 550 kilometers (350 mi) over months. By May, only 120 remained alive. During the march, Gerda held her best friend as she died in her arms. She had already lost her parents, brother, and 64 other members of her family. When the remaining women were too weak to continue, they were abandoned in a derelict factory. Gerda weighed a mere 30 kilograms (68 lb).

On May 7, a car pulled up to the factory. Gerda stood at the doorway as two American soldiers stepped out. Among them was Kurt Klein, a Jewish man who had fled Germany for the US before the war. “He looked like God to me,” Gerda recalled. When Kurt asked about the other women, he called them “ladies,” a term Gerda hadn’t heard in over six years.

As Kurt opened the door for her to enter, Gerda felt a profound sense of “restoration of humanity, of dignity, of freedom.” They married a year later in Paris, had two daughters, and devoted their lives to improving the world.

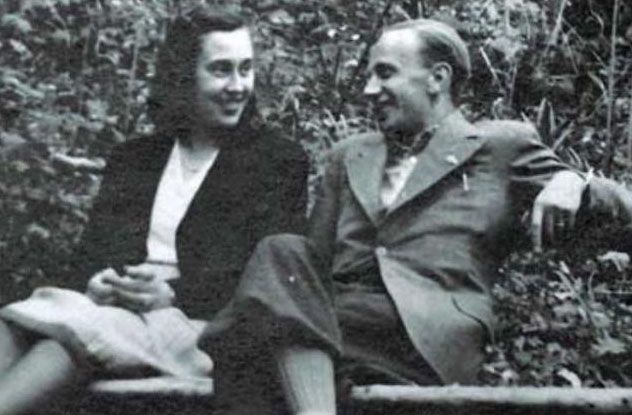

1. Joseph And Rebecca Bau

Love was strictly prohibited among Jews in the Nazi concentration camps. Yet Joseph Bau and Rebecca Tennenbaum were not individuals who submitted to Nazi authority. Before his imprisonment, Joseph had used his artistic talents to forge documents that saved hundreds of lives. On February 13, 1944, the couple married in the women’s barracks at the Plaszow forced-labor camp. Had they been discovered, everyone present would have been executed.

The couple fashioned their wedding rings from a spoon. Later, Joseph was freed from the camp by Oskar Schindler, and their wedding was depicted in the film Schindler’s List. Although Rebecca’s name was originally on the list, she swapped it with Joseph’s, sending herself to Auschwitz and certain death. Remarkably, she survived, and after the war, the couple was reunited.

Their wedding is now celebrated as a symbol of hope. In 2014, during celebrations for what would have been their 70th anniversary, their daughter Cilia shared, “According to Jewish tradition, when in the deepest despair, a wedding ceremony would take place in a cemetery, symbolizing the connection between the living and the dead.” The Plaszow camp had been constructed on top of a cemetery.