While Greek and Roman mythologies dominate Western culture, the rich polytheistic traditions of other civilizations often go unnoticed. Among these, the Slavic pantheon of deities, spirits, and legendary figures remains one of the most obscure, having thrived both before and after the arrival of Christian missionaries in the region.

Slavic mythology stands apart from Greek and Roman traditions in two significant ways. Firstly, many of its supernatural entities continue to influence modern Slavic folklore and imagery. Secondly, due to limited historical records, researchers have pieced together the ancient Slavic pantheon using indirect sources, making it a captivating yet enigmatic subject worth exploring.

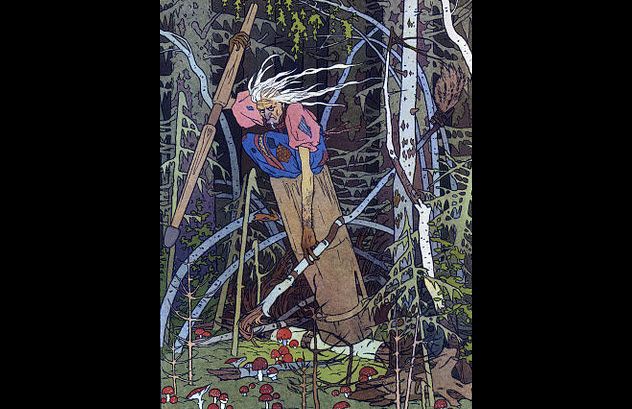

10. Baba Yaga

Baba Yaga stands out as a uniquely Slavic figure in mythology. Unlike many other Slavic deities and beings, she has no direct counterpart in Greek or Roman traditions.

At first glance, Baba Yaga resembles witches found in European folklore. She is depicted as an elderly woman with a long nose and thin legs. Her encounters with travelers often result in either blessings or curses, depending on her whims.

However, Baba Yaga possesses several distinctive traits. Her home is a hut perched on chicken legs, enabling it to move. When she ventures out, she travels in a mortar, using a pestle to propel herself.

While Baba Yaga wields a broom like typical witches, she uses it to erase her tracks. In some tales, she is portrayed as one of three sisters, all sharing the same name.

The origins of Baba Yaga tales remain unclear. Unlike many other Slavic mythological figures, her stories remained popular well into the 20th century. Her enduring appeal lies in her ambiguous morality. Travelers journeyed from distant lands seeking her counsel, hoping to gain profound wisdom.

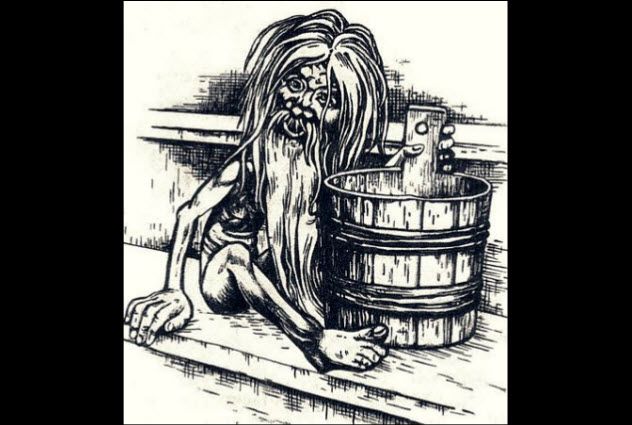

9. Bannik

The banya steam bath holds significant cultural importance in Eastern Europe, particularly in nations like Russia and Ukraine. These baths are especially popular during winter and are believed to offer numerous health benefits.

Historical Russian texts frequently reference the banya, which was even utilized during childbirth. Given its social and cultural significance, Slavic folklore introduced a banya spirit called Bannik.

Bannik was a troublesome spirit who seldom acted kindly. He was depicted as an elderly man with elongated claws. Bathhouse visitors would always vacate during the third or fourth session to respect Bannik’s privacy, expressing gratitude by leaving him soap offerings.

Legends claim Bannik could foretell the future. When questioned, he would gently touch the back of those destined for good fortune or brutally flay those facing misfortune. Anger would drive him to skin those who provoked him.

Since the banya often served as a birthing site, Russian traditions included methods to prevent Bannik from disrupting deliveries. Midwives were tasked with warding off the spirit during childbirth in the banya.

Folklore warns that Bannik would devour or skin children in the banya. To distract him, midwives would soak stones in water and hurl them into the bathhouse corners.

The banya played a crucial role in wedding traditions. To ensure the safety of the newlyweds, guests would hurl rocks and pottery at the bathhouse walls from outside, aiming to drive Bannik away before the couple entered the steam bath together.

8. Zduhac

In pre-Christian Slavic societies, witchcraft held significant cultural importance. Witches and wizards were often tasked with safeguarding people and territories from malevolent spirits. Among these protectors, the zduhacs stood out as men endowed with supernatural abilities to defend their villages and even launch attacks on neighboring settlements.

The origins of the zduhac tradition remain a mystery to scholars, though it is believed to have evolved from the practices of Eurasian shamans. This shamanic influence likely migrated westward with Finno-Ugric and Uralic tribes from Siberia.

The ancient Slavs, known for their superstitions, easily embraced the concept of a supernatural guardian. Every village boasted its own zduhac, who would engage in battles with the zduhac of neighboring villages, often clashing in the skies above.

In some tales, the rival zduhacs took on animal forms to wage their battles. When not shape-shifting, they wielded an array of mystical weapons, such as sticks charred at both ends, which served as powerful talismans.

There are differing accounts of how a zduhac acquired their abilities. Some legends attribute their power to enchanted garments, while others suggest they gained their strength through pacts with demonic entities.

The zduhac tradition persisted well into modern Slavic culture, particularly in Montenegro. While they no longer served as village protectors, folklore often identified prominent figures, such as the Montenegrin general Marko Miljanov and other spiritual leaders, as the contemporary embodiments of zduhacs.

7. Domovoi

In pre-Christian Slavic mythology, the domovoi were revered as household spirits. Despite the efforts of Christian missionaries to eradicate pagan beliefs among Slavic converts, the traditions surrounding the domovoi endured for centuries.

The domovoi were considered guardians of the home, often depicted as benevolent entities. They are typically portrayed as small, bearded, male figures, resembling Western European household spirits like hobgoblins.

A domovoi would frequently assume the appearance of the household's patriarch to carry out tasks and safeguard the home. Numerous tales describe a domovoi laboring in the yard, mimicking the head of the family, while the actual person slept soundly indoors. On rare occasions, the domovoi might transform into a cat or dog.

When the family he guarded was disrespectful or untidy, the domovoi would torment them in poltergeist-like fashion, playing minor tricks until the household improved its behavior.

The domovoi also served as a harbinger of events. Joyful dancing and laughter from the spirit signaled impending good luck, while combing its bristles foretold an upcoming wedding. However, if it snuffed out candles, it was a sign of looming misfortune.

The domovoi legend persisted well into the 20th century, occasionally surfacing in Russian artistic works.

6. Kikimora

In Slavic folklore, the kikimora stood in stark contrast to the domovoi, representing a malevolent household spirit. This entity was particularly prominent in Polish and Russian tales.

The kikimora was often depicted as a witch or the restless soul of the dead, dwelling within the home and bringing misfortune. She typically resided behind the stove or in the cellar, creating disturbances to demand food. Her presence was especially menacing in households that were disorganized or unclean.

Slavic lore suggests that the kikimora could slip into a home through the keyhole, targeting sleeping individuals to choke them. She would sit on her victims, inducing suffocation. Ancient Russians believed the kikimora was responsible for episodes of sleep paralysis.

To ward off the kikimora, people would recite intricate prayers or position brooms by the entrance. In Polish customs, children were advised to mark their pillows with the sign of the cross to keep the kikimora at bay.

While encounters with a kikimora could pose serious danger, she was often more of a nuisance, primarily aiming to frighten the inhabitants of the home.

If the house was messy or disorganized, the kikimora would whistle and shatter dishes. However, if she approved of the household, she would assist with tasks like tending to chickens and other domestic duties.

The kikimora, deeply rooted in Slavic folklore, frequently appears in tales and musical works. A newly identified spider species was even named in her honor.

5. Mokosh

In pre-Christian times, Mokosh was revered as the Slavic deity of fertility, prominently featured in Russian and Eastern Polish folklore. Initially serving as an attendant to Mat Zemlya, the nature deity, Mokosh's worship eventually surpassed that of her counterpart.

Mokosh's veneration persisted into the 19th century, and she remains a celebrated figure in contemporary Russia. While her origins trace back to Finno-Ugric tribes, her influence expanded across Slavic regions, reflected in the Finnish roots of her name.

Mokosh was portrayed as a nomadic figure associated with spinning, childbirth, and safeguarding women. She was viewed as the source of life, bestowing children and favorable weather. Rain was believed to be her breast milk, nourishing the earth.

Devotion to Mokosh involved fertility ceremonies and offerings to boulders shaped like breasts. The Slavs dedicated the final Friday of October to honor her. Festivals in her name featured dancing in dual circles, symbolizing life in the outer ring and death in the inner one.

Christian missionaries tried to eradicate Mokosh worship by substituting her with the veneration of Mother Mary. Despite their efforts, Mokosh remains a significant and enduring figure in Slavic mythological traditions.

4. Radegast

Radegast stands as one of the most ancient deities in Slavic mythology, largely reconstructed from indirect historical sources. His name derives from two archaic Slavic terms signifying 'beloved guest.'

Based on this linguistic origin, scholars infer that Radegast was revered as the deity of feasts and hospitality. It is thought that those hosting celebrations would extend a formal invitation to him.

According to tradition, Radegast would appear clad in black armor, wielding a sphere. Experts suggest he held significant importance for rulers and governing bodies.

The individual chosen to preside over a town council was often referred to as Radegast during the assembly. Consequently, Radegast became integral to the political and economic fabric of Slavic society.

Reconstructing Radegast's mythology is challenging due to the concerted efforts of Christian missionaries to eradicate his worship. A prominent statue of Radegast once stood on Mt. Radhost in what is now the Czech Republic, but it was demolished by the missionaries Cyril and Methodius.

Legend has it that in 1066, Slavic pagans offered Christian bishop Johannes Scotus as a sacrifice to Radegast. This act, during the Christianization period, intensified the missionaries' efforts to eliminate Radegast worship, leading to the loss of many primary records.

In contemporary culture, the legacy of Radegast endures, partly due to author J.R.R. Tolkien naming one of his wizard characters after him.

3. Perun

While some scholars debate, most agree that Perun, the thunder deity, was regarded as the supreme god by the ancient Slavs. Perun is frequently mentioned in ancient Slavic writings, and his symbols are prevalent in Slavic artifacts. He held the highest position in their divine hierarchy.

Perun, the god of thunder and war, was depicted riding a chariot and wielding legendary weapons. His most famed tool was his axe, which he hurled at evildoers, only for it to return to his grasp. He also battled with stone, metal weapons, and fiery arrows.

To unleash ultimate destruction on his foes, Perun employed enchanted golden apples, symbols of total ruin. His portrayal always featured a robust, bronze-bearded figure, emphasizing his formidable nature.

In Slavic myths, Perun engaged in battles with Veles for control over humanity, consistently emerging victorious and consigning Veles to the underworld. This cemented Perun's status as the paramount deity.

In 980, Prince Vladimir the Great commissioned a statue of Perun outside his palace. As Russian influence expanded, Perun's worship grew among Eastern Europeans and became deeply ingrained in Slavic culture.

Upon their arrival in Russia, Christian missionaries sought to divert the Slavs from their pagan practices. In the East, they equated Perun with the prophet Elijah, transforming him into a revered saint.

In the West, missionaries substituted Perun with St. Michael the Archangel. Gradually, Perun's attributes merged with those of the Christian God. Despite this, Perun's veneration persisted, with celebratory feasts held annually on July 20 to honor the thunder deity.

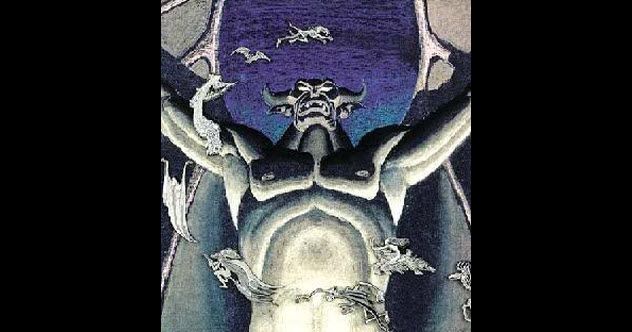

2. Veles

In many ancient mythologies, there exists a deity symbolizing evil and another representing supreme good. Veles embodies the malevolent force in Slavic lore, perpetually at odds with Perun, his virtuous brother and the god of thunder.

Researchers have uncovered numerous sources highlighting Veles' significance to the ancient Slavs. In their myths, Veles governed the earth, waters, and underworld as a supernatural entity. He was also linked to magic and livestock.

Legends recount Veles' battles with Perun, culminating in his defeat. While no direct sources for this myth survive, scholars have pieced it together using Slavic folk songs, secondary accounts, and parallels from other Indo-European traditions.

The Slavs believed Veles and Perun were locked in eternal conflict, with Perun safeguarding humanity from Veles. Despite this, temples honoring Veles were constructed, often in low-lying areas like valleys. He was also revered by musicians and associated with prosperity.

The ancient Slavs did not strictly categorize Veles as entirely evil, lacking a clear good-versus-evil dichotomy. However, Christian missionaries, aiming to eradicate Slavic paganism, equated Veles with the Christian Devil. Over time, Veles' depiction absorbed traits of the biblical Satan.

1. Chernobog

Among the Slavic gods, Chernobog stands out as the most recognized by the public. He gained fame through Disney’s Fantasia and played a significant role in Neil Gaiman’s acclaimed novel American Gods, which is set for a television adaptation.

Interestingly, Chernobog is one of the more enigmatic figures in Slavic mythology. Primary sources about him are scarce, and much of what is known comes from Christian interpretations.

The earliest mention of Chernobog dates back to the 12th century, recorded by Father Helmold, a German priest. Helmold described Slavic rituals involving Chernobog, such as passing bowls in a circle and murmuring incantations to ward off his malevolence. His writings reveal that Chernobog symbolized the embodiment of evil, depicted as a devilish figure cloaked in darkness.

While the extent of Chernobog's influence in ancient Russia remains uncertain, it appears to have been particularly significant in northern regions. His role often overlapped with Veles, the malevolent deity from earlier Slavic mythology.

Traces of Chernobog can also be found in Slavic idiomatic expressions. The phrase do zla boga, meaning 'go to the evil god,' serves as a curse. Additionally, the term 'evil god' is used to amplify adjectives, reflecting Chernobog's conceptual impact on early Slavic language and thought.