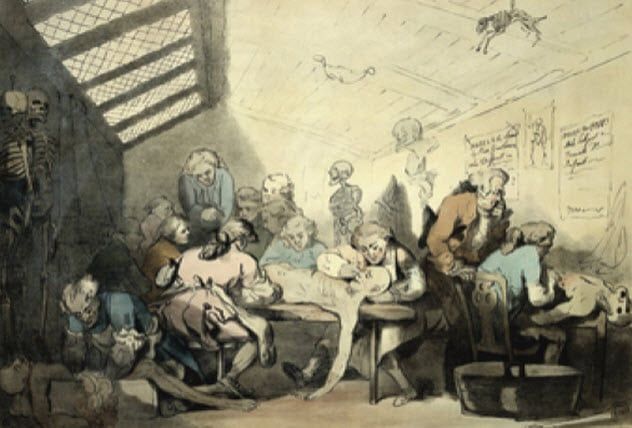

During the early 19th century, both Britain and America were immersed in a surge of scientific and medical advancements. The exploration of anatomy and surgical techniques gained immense popularity, sparking a macabre trade in human cadavers, a phenomenon that echoed globally.

Families mourning their loved ones could no longer rest assured that their graves would remain undisturbed. Grave robbers, known as resurrectionists, prowled cemeteries under the cover of darkness, targeting recently buried bodies. They would exhume the corpses, strip them of clothing, discard the garments back into the graves, and smuggle the bodies away. These stolen cadavers were then dissected, often in public demonstrations, purportedly for the advancement of medical science.

Understandably, many relatives were outraged by this practice and devised a variety of clever methods to outsmart the body snatchers.

10. Mort Safes

Mort safes were robust iron cages designed to encase coffins, shielding them from the grasp of grave robbers. These protective barriers remained in place for as long as 10 weeks, ensuring the bodies decomposed to a state where they were no longer viable for dissection. In some cases, the cages were never removed, becoming a permanent fixture over the graves.

During this period, Edinburgh was renowned for its prestigious surgical school, serving as a hub for anatomical and surgical studies. The city also had a steady influx of cadavers, largely due to the infamous activities of two locals—Mr. William Burke and Mr. William Hare. Surgeons’ Hall Museums in Edinburgh delve into the darker aspects of surgical history, even featuring an interactive dissection table for visitors to try their hand—though, thankfully, not on actual human remains!

However, the residents of Edinburgh were far from pleased with these practices. Traces of mort safes can still be observed at Greyfriars Kirkyard, alongside various other measures taken by the community to thwart the unauthorized exhumation of the deceased.

9. Iron Coffins

Affluent families occasionally opted to craft entire coffins from iron to deter body snatchers from accessing the remains. At St. Brides Church on Fleet Street in London, an iron coffin, securely riveted and dated 1819, was unearthed. Similarly, the remains of a boy found in an iron coffin near Washington are thought to originate from the 1850s.

Several patented coffins were marketed as tamperproof, with iron coffins being especially popular. These heavy caskets necessitated specialized lifting equipment for burial, often causing reluctance among cemetery caretakers to accept them.

In one notable instance, a woman’s body remained unburied in her coffin for three months as courts deliberated whether cemetery authorities had the right to deny her interment. This delay rendered the protective measures somewhat pointless.

8. Mort Houses

Mort houses were heavily fortified and guarded structures designed to store bodies before burial, ensuring they decomposed to a state unsuitable for dissection. Families could pay a fee to keep multiple bodies in these facilities for several weeks until decomposition rendered them useless to grave robbers.

The design of mort houses was exceptionally secure, often resembling prisons or bank vaults. For instance, the mort house in Belhelvie near Aberdeen was constructed from massive granite blocks, featuring a single entrance accessed via three stone steps and protected by a set of double doors.

The inner door was reinforced with iron sheets and secured with a heavy-duty lock. The outer door, crafted from sturdy oak planks, was reinforced with iron bolts and equipped with two large mortise locks. Both keyholes were shielded by iron bars—one hinged at the top and the other at the bottom—intersecting and secured with an enormous padlock.

Only the most determined body snatcher would stand a chance of breaching such defenses.

Scotland was home to numerous mort houses, including one in Udny that featured a rotating coffin platform, simplifying the process of adding or removing bodies.

7. Delaying Burial

For those unable to afford mort house services, the alternative was to keep the deceased at home until the body had sufficiently decomposed. This was hardly a desirable option for most families.

Grieving families would often mix the burial earth with an equal amount of straw to hinder grave robbers from easily exhuming the body. However, while the wealthy could afford elaborate protective measures, the remains of the less fortunate were left far more exposed.

The consequences for grave robbing were relatively lenient, provided the thieves did not take any belongings of the deceased. This explains why the clothes were often discarded back into the grave.

Individuals who died in workhouses were particularly at risk. Hospitals claiming to be charitable would frequently sell unclaimed bodies of inmates directly to dissection facilities. Grave robbers sometimes went as far as having someone pose as a relative to claim the bodies. Tragically, these individuals were often more valuable in death than they were in life.

6. Mort Stones

Graves were most vulnerable to theft in the initial weeks after burial, when the body was still fresh and the soil had not yet settled. As a short-term solution, mort stones were occasionally placed over the grave to deter robbers.

In the graveyard near Inverurie, close to Aberdeen, several mort stones remain visible today. These massive granite slabs matched the size of the burial plots, entirely covering the coffins below. Special lifting equipment was necessary to position them and later remove them after decomposition, allowing space for a headstone to be placed.

In 1816, Superintendent Gibb of Aberdeen Harbor Works donated a mort stone, priced at half a crown, to St. Fitticks churchyard. The lifting machinery, however, was far more expensive and had to be securely stored under lock and key to prevent grave robbers from accessing it.

5. Vigils

Families frequently took shifts guarding gravesites nightly during the first week to ward off grave robbers. Spending dark, lonely hours beside a grave, anticipating the arrival of thieves, was undoubtedly a challenging task. Yet, the fear of body snatchers drove many to endure it.

Many believed that a body needed to remain intact to enter Heaven. Thus, dissectors were seen not only as stealing the deceased’s remains but also robbing them of eternal peace.

A churchyard in Somerset, England, tells the sorrowful story of Miss Rogers, who was engaged to a sailor. He was returning home to marry her, but his ship sank, and he drowned.

In a tragic twist reminiscent of Gothic tales, his fiancée passed away shortly after, heartbroken. She was laid to rest in her wedding gown, adorned with all her jewelry. Around that time, rumors spread that grave robbers were seeking fresh corpses for surgical purposes. The family’s servants kept watch over her grave every night until a mort stone could be placed over it.

4. Watchmen

Those unwilling to spend nights guarding graves often hired watchmen. For instance, the parish of Ely employed a watchman to remain “constantly in the churchyards to protect the buried bodies.”

In larger churchyards, watchhouses were constructed to provide shelter for watchmen between shifts. One such structure near Aberdeen features a two-story tower, with the upper level serving as a lookout. It includes a hole for firing at intruders and a bell atop the tower to sound alarms and call for help.

Some grave robbers disguised themselves as watchmen, giving them insider knowledge of all the protective measures. Others collaborated with body snatchers, receiving a share of the profits from the sale of stolen bodies.

Being a trustworthy watchman was a perilous job. When bribery or threats failed to sway the watchmen, grave robbers would resort to violence if caught. In one instance, a guard was attacked with a saber.

3. Booby Traps On Graves

The animosity toward dissectors was so intense that some mourners installed booby traps on graves. They buried spring-loaded guns and sharp objects in the ground. In Dublin, a grieving father reportedly went as far as placing a landmine in his infant child’s coffin.

The authenticity of the landmine remains uncertain. Unsurprisingly, no grave robber dared to test its validity.

Public outrage against body snatchers reached a peak, with citizens urging authorities to take action to safeguard the deceased. The introduction of the 1832 Anatomy Act in England, along with similar legislation in America and other regions, abruptly halted the illegal trade in human remains.

The new laws permitted the acquisition of bodies for medical research from various sources, particularly the poor and those without next of kin. This allowed surgeons, medical students, and scientists to advance their understanding of human anatomy while ensuring the deceased could rest in peace.

2. Coffin Collars

A more practical solution was the coffin collar. This device consisted of a heavy iron ring attached to a sturdy oak board, firmly bolted to the coffin’s base. It made removing the corpse impossible without severing the head, drastically reducing its value to grave robbers.

This was an affordable and effective way to thwart resurrectionists, with evidence of their use found in Scotland churchyards. While the collars were unsightly and noticeable in open caskets, they provided grieving families with much-needed reassurance.

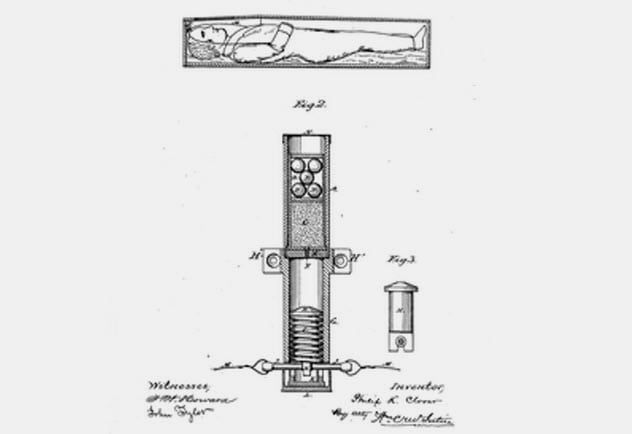

1. Coffin Torpedoes

One of the more inventive burial security measures was the coffin torpedo.

Invented in 1878 by Philip K. Clover in Columbus, Ohio, the coffin torpedo was created to “effectively stop the unauthorized exhumation of bodies; and . . . be easily attached to the coffin and the corpse in such a way that any attempt to remove the body after burial would trigger the torpedo’s explosive charge, potentially injuring or killing the grave violator.”

The torpedo’s complex mechanism was designed to detonate “with lethal force” if the coffin was tampered with. The legal implications of such a weapon seem to have been largely overlooked.

Fortunately for Mr. Clover, there’s little indication that the coffin torpedo was ever mass-produced. Graveyards were already perilous places, with body snatchers armed with sabers prowling at night and watchmen firing at intruders through walls—adding explosives to the equation would have only heightened the danger.