Long before making history as the first African-American Supreme Court Justice, Thurgood Marshall had already cemented his legacy as a trailblazing civil rights advocate. As a lawyer for the NAACP during the 1940s and 1950s, he presented 32 cases before the Supreme Court, securing victories in 29, including pivotal rulings on school segregation and voting rights. Beyond his iconic role in the civil rights movement of the 1950s, Marshall also played a critical role in addressing issues like police brutality, women’s rights, and the death penalty.

More than five decades after his groundbreaking appointment to the Supreme Court, Marshall is celebrated not only for his pioneering legal achievements but also for his vibrant personality. (He was an avid viewer of Days of Our Lives and, as solicitor general, was renowned for sharing bourbon and spinning tall tales with President Lyndon Johnson.) On the 110th anniversary of his birth, here are some fascinating details about this civil rights icon and legal luminary.

1. HIS NAME WASN’T ORIGINALLY THURGOOD.

Thoroughgood Marshall was born in Maryland in 1908. As a young boy, Thoroughgood decided to simplify his name to Thurgood. He once shared, “By the time I got to the second grade, I grew tired of spelling it all out and shortened it to Thurgood.”

2. HIS FATHER INSPIRED HIS LEGAL CAREER.

Growing up in Baltimore, Marshall’s fascination with the law began when his father William, a steward at a country club, brought him to watch court proceedings. Their dinner table conversations often turned into lively debates, with William challenging every point Thurgood made. Reflecting on his father’s influence in 1965, Marshall remarked, “He never told me to become a lawyer, but he shaped me into one.”

3. EARLY IN HIS CAREER, MARSHALL CHAMPIONED EQUAL PAY FOR AFRICAN-AMERICAN TEACHERS.

While attending Lincoln University, where he graduated with honors in 1930, Marshall’s family faced financial difficulties. His mother, Norma, a teacher, negotiated each semester with the registrar to delay tuition payments until she could gather enough funds to cover the costs.

After graduating from Howard University’s law school in 1933, Marshall took on the issue of equal pay for African-American teachers. In 1939, he achieved a significant victory when a federal court ruled against pay discrimination for African-American teachers in Maryland. Marshall continued his fight for pay equality in 10 Southern states. His most famous cases, including Brown v. Board of Education (1954), focused on combating discrimination in public education.

4. DURING HIS EARLY CAREER, HE BALANCED A NIGHT JOB AT A BALTIMORE HEALTH CLINIC WHILE HANDLING MAJOR LEGAL CASES.

As a young attorney, Marshall struggled financially and took on a second job at a clinic treating sexually transmitted diseases in 1934. He continued working there even while preparing for the historic case to desegregate the University of Maryland. When he relocated to New York in 1936, Marshall didn’t formally resign from the clinic—instead, he requested a 6-month leave, as noted by biographer Larry S. Gibson. However, he never went back. By 1940, he had risen to become the Director-Counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.

5. MARSHALL FACED LIFE-THREATENING RISKS IN HIS CIVIL RIGHTS WORK.

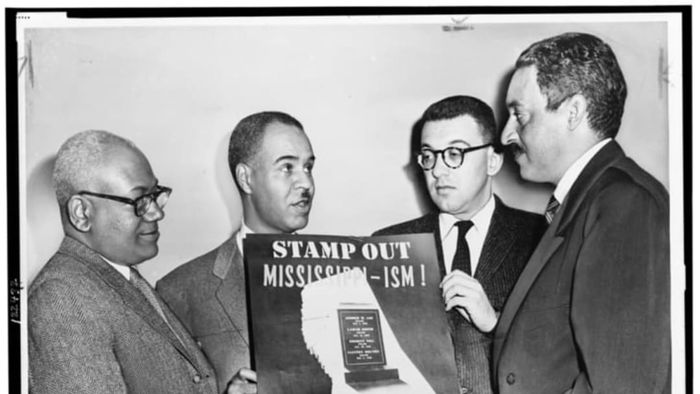

Marshall (far right) stood alongside NAACP leaders, holding an NAACP sign. From left to right: Henry L. Moon, director of public relations; Roy Wilkins, executive secretary; and Herbert, labor secretary. | Al. Ravenna, Library of Congress

Marshall (far right) stood alongside NAACP leaders, holding an NAACP sign. From left to right: Henry L. Moon, director of public relations; Roy Wilkins, executive secretary; and Herbert, labor secretary. | Al. Ravenna, Library of CongressIn 1946, while representing the NAACP, Marshall traveled to Columbia, Tennessee, to defend a group of African-American men. After the trial, fearing for their safety, Marshall and his team attempted a quick exit. However, as biographer Wil Haygood recounts, they were ambushed by locals on their way to Nashville. Marshall was falsely arrested, taken into a sheriff's car, and driven off the main road. His colleagues, instructed to continue to Nashville, followed the car, which eventually returned to the main road. Marshall later stated that he would have been lynched had his colleagues not intervened.

6. DURING THE RED SCARE, HE WAS BOTH AN INFORMANT AND A TARGET OF FBI SURVEILLANCE.

During the 1950s, Marshall alerted the FBI about communist efforts to infiltrate the NAACP. Simultaneously, he became a target of FBI investigations led by J. Edgar Hoover. FBI records reveal that critics attempted to link Marshall to communism through his association with the National Lawyers Guild, a group labeled as “the legal bulwark of the Communist Party” by the House Un-American Activities Committee. Despite these efforts, when Marshall was nominated to the Supreme Court, the FBI found no evidence of communist ties.

7. DESPITE INITIAL CHALLENGES, PRESIDENT KENNEDY APPOINTED MARSHALL TO HIS FIRST JUDICIAL POSITION.

In 1961, President John F. Kennedy sent his brother Bobby to discuss civil rights with Marshall. However, Marshall didn’t connect well with the Kennedys and felt his expertise was being overlooked. Marshall recalled that Bobby “spent the entire time telling us what we should do.” Despite this, Kennedy nominated Marshall to the U.S. Court of Appeals a few months later. The Senate took a full year to confirm his nomination, facing strong opposition from several southern Senators.

8. IN 1967, PRESIDENT LYNDON JOHNSON CREATED A VACANCY TO NOMINATE MARSHALL TO THE SUPREME COURT.

In 1967, President Johnson aimed to appoint Marshall to the Supreme Court but faced no available seat. To resolve this, Johnson orchestrated a political strategy. The most widely accepted account states that Johnson appointed Ramsey Clark, the son of Justice Tom Clark, as Attorney General. This move prompted the elder Clark, concerned about a conflict of interest, to retire on June 12, 1967. Johnson formally nominated Marshall as his replacement the following day.

9. MARSHALL FACED A GRUELING SENATE CONFIRMATION PROCESS BEFORE JOINING THE SUPREME COURT.

Marshall was officially sworn in as a Supreme Court Justice on October 2, 1967. However, his confirmation process was arduous, as southern senators attempted to block his nomination. Over four days in July 1967, these senators grilled Marshall on his legal views and administered a test on political history, resembling a Jim Crow-era literacy test. Marshall endured more hours of questioning than any previous Supreme Court nominee. Ultimately, on August 30, the Senate approved his nomination.

10. HIS LEGACY REMAINS A TOPIC OF DISCUSSION.

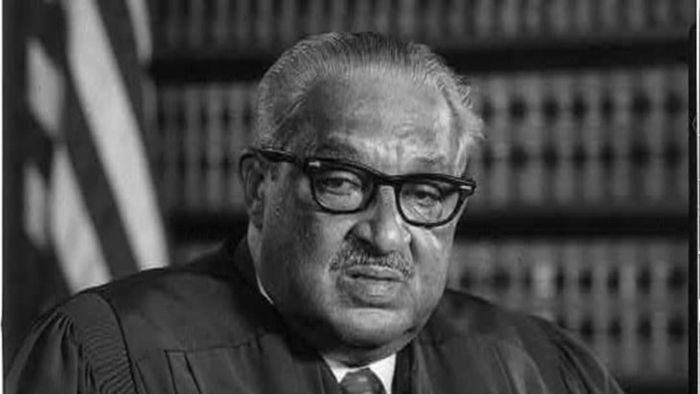

Official U.S. Supreme Court portrait of Justice Thurgood Marshall in 1976 | Robert S. Oakes, Library of Congress

Official U.S. Supreme Court portrait of Justice Thurgood Marshall in 1976 | Robert S. Oakes, Library of CongressThroughout his time on the Supreme Court, Marshall maintained a flawless record of advocating for affirmative action and opposing the death penalty. However, by the 1980s, he became increasingly disillusioned with the Court and retired in 1991. In 2010, President Barack Obama nominated Elena Kagan, one of Marshall’s former clerks, to the Supreme Court. During her confirmation hearing, senators scrutinized her ties to Marshall and questioned his judicial legacy. Kagan, however, praised him warmly: “He was a man who opened doors for countless individuals and transformed lives. I consider him a hero and the most influential lawyer of the twentieth century.”