Frank Abagnale's masterful cons in Catch Me If You Can earned widespread admiration for their sheer brilliance. Yet, history is filled with less impressive fraudsters who, against all odds, managed to deceive countless individuals. The imposters listed here should have been easily exposed—but astonishingly, they weren't.

10. Martin Guerre

The Middle Ages provided fertile ground for identity theft. In an era devoid of identification records and widespread literacy, the concept of personal identity was remarkably flexible. This context sheds light on the audacious actions of Arnaud du Tilh. One summer day in 1556, Arnaud boldly entered the Basque village of Hendaye, declaring himself to be the missing Martin Guerre.

The genuine Guerre had vanished eight years prior to enlist in the Spanish army, leaving behind his young wife Bertrande without a trace. Remarkably, Bertrande seemed to accept the imposter’s tale, embracing the new “Martin” wholeheartedly. The townspeople were equally convinced—without photographs, few could recall Martin’s exact appearance. For three years, Bertrande enjoyed a blissful life with her “returned” husband, who she found far more considerate than the original Martin.

Eventually, inconsistencies emerged in the new Martin’s account—most notably, he could no longer speak Basque. His athleticism had vanished, and his children bore no resemblance to him. Additionally, his plan to sell ancestral land was unheard of for a Basque. Martin’s uncle soon accused him of fraud, taking the case to court.

The initial trial ruled that “Martin” was an imposter, but an appeal acquitted him, nearly allowing him to escape punishment. However, in a dramatic courtroom twist, the real Martin Guerre arrived with a wooden leg, instantly exposing Arnaud du Tilh as a fraud. Arnaud was sentenced to death, leaving Bertrande in an embarrassing predicament.

9. Lobsang Rampa

Among the most improbable stories is that of an Irish plumber who claimed to be possessed by the spirit of a deceased Tibetan lama. Yet, “Lobsang Rampa,” also known as Cyril Hoskins, continues to sell thousands of books annually, captivating readers with his extraordinary tale.

In the 1950s, Hoskins burst onto the scene with the bestselling book The Third Eye, recounting his supposed past life as the lama Lobsang Rampa. Hoskins claimed this revelation came to him after a fall from a tree left him with a head injury.

The Third Eye was packed with outlandish assertions, including the existence of Yetis, lamas soaring on mystical kites, and the geologically implausible theory that the Himalayas were created by a planetary collision. Most astonishingly, Hoskins insisted he had undergone a surgical procedure to implant a “third eye” in his forehead. Strangely, he claimed to have forgotten how to speak Tibetan and would react violently when questioned about it.

Buddhist expert Agehananda Bharati succinctly critiqued Hoskins’ work: “The first two pages revealed the author wasn’t Tibetan, the next ten confirmed he had never visited Tibet or India, and that he lacked any knowledge of Buddhism.” Anthropologists repeatedly debunked “Lobsang” as a fraud, yet he never addressed their claims. Despite this, his books sold in the tens of thousands. The Third Eye and its sequels played a key role in introducing Buddhism to the West, though they also linked the religion to New Age mysticism, a misconception that persists today.

8. Tile Kolup

If people don’t believe you’re the deceased Holy Roman Emperor, persistence is key. This was the philosophy of Tile Kolup, who first proclaimed himself to be Frederick II in Cologne in 1284. Given that Frederick had died in 1250, he would have been well over 90. Unimpressed, the citizens of Cologne tossed Kolup into a sewer and drove him out of the city.

Undeterred, Kolup moved to Neuss, where the locals were far more gullible—they welcomed him as Frederick II with open arms. Kolup’s success stemmed from his extensive knowledge, enabling him to craft convincing imperial documents. He also capitalized on the “King in the Mountain” myth, which claimed legendary heroes would awaken in times of need.

Kolup further amazed people by seemingly predicting the names of those he met. These tactics convinced many of his legitimacy, and for several months, he ruled a makeshift imperial court in Neuss, even minting coins in his name.

Naturally, the real Holy Roman Emperor, Rudolf, was far from pleased. When he arrived to confront the imposter, Kolup’s followers quickly realized a 95-year-old Frederick wouldn’t inhabit a 30-year-old’s body. Kolup was swiftly declared a heretic and burned at the stake, marking an awkward chapter in German history.

7. Yemelyan Pugachev

Historically, Russia has been remarkably susceptible to imposters, including a man who briefly ruled by claiming to be Ivan the Terrible’s deceased son Dmitri. Shortly after his downfall, two more Dmitris emerged. By the 1760s, seven individuals had declared themselves to be the resurrected Tsar Peter III.

Among these pretenders, only the seventh, an uneducated Cossack named Yemelyan Pugachev, gained significant traction. Pugachev, a rugged, dark-complexioned man with a thick black beard, looked nothing like the real Peter. Compounding the issue was the well-known fact that Peter had been assassinated in 1762, over a decade before Pugachev’s uprising began.

However, facts rarely deterred Russian belief. The Cossacks, in particular, despised Catherine the Great’s rule, as she had reversed many of Peter’s pro-serf policies. Her decision to tax serfs for growing beards further alienated the fiercely independent Cossacks.

In September 1773, Pugachev released a manifesto urging Cossacks and Tatars to rally behind him as the true Tsar Peter III and help reclaim his throne. Thousands joined his cause, enabling him to seize control of the Volga region. His early victories were bolstered by the Russian military’s focus on the Ottoman border. For two years, Pugachev’s forces wreaked havoc along the Volga, even capturing the city of Kazan.

Once the Ottoman conflict was settled, Catherine directed her full military force against the man claiming to be her husband. The rebellion was swiftly defeated, and Pugachev was transported to Moscow in a cage. His story, however, lived on—he was later eternalized in Pushkin’s romantic work The Captain’s Daughter.

6. Iron Eyes Cody

During the early 1970s, the environmental movement gained momentum with the iconic “Crying Indian” campaign. In the memorable PSA, Iron Eyes Cody, portraying a Native American man, sheds a tear as he witnesses the devastation of pollution on his homeland. This powerful ad spurred nationwide recycling initiatives and heightened environmental awareness among Americans.

Iron Eyes Cody, who claimed to be the child of a Cree mother and Cherokee father, became a prominent figure in ads, films, and TV shows as a Native American. However, his true identity was revealed—he was born Espera Oscar de Corti and was fully Italian. Cody’s commitment to his role was so intense that he always appeared in traditional Native attire and even married a Native American woman.

Cody’s hometown of Kaplan, Louisiana, knew he was Italian, but they took pride in his success and kept his secret. Iron Eyes continued portraying Native American characters until his death. His image is estimated to have been seen over 14 billion times, making him the most viewed “Native American” in history—despite not being one.

5. Nadezhda Durova

While some people turn to hobbies like music or marriage when bored, Nadezhda Durova chose to enlist with the Cossacks and battle Napoleon. However, there was a significant hurdle—Durova was a woman, and Russia during the Napoleonic Era was far from progressive. To overcome this, she disguised herself as a man, convincing her superiors she was a nobleman who had rebelled against his family to serve in the military.

This couldn’t have been further from reality, as Durova’s father was a general who had included her in his campaigns since childhood. At just four years old, she was thrown from a moving carriage and nearly left for dead. These experiences shaped her into the kind of woman who could convincingly join the Cossacks.

In her first battle against the French, Durova participated in every attack, unable to tolerate inactivity. Her courage caught the attention of Tsar Alexander I, who quickly saw through her disguise. Despite his initial suggestion for her to return home, Durova persuaded him to let her continue serving. She remained in the military until Napoleon’s defeat in 1815. Though her gender barred her from promotion, her youthful appearance kept her secret intact, and she retired as a respected soldier in the Russian army.

4. Bampfylde Moore Carew

Born into British aristocracy, Bampfylde Moore Carew chose a life of deception, masquerading as a destitute gypsy. As a youth, he fled to join a group of travelers and earned the title “King of the Beggars.” Embracing the nomadic lifestyle, Carew became infamous for adopting new identities daily, ranging from a clergyman or sailor to a ratcatcher, lunatic, or even an elderly woman.

He even duped aristocrats near his hometown into giving him money, despite their likely familiarity with him. Carew also exploited natural disasters reported in newspapers, posing as a victim to solicit sympathy. Even after being captured and exiled to America as a convict, he escaped and returned to England—twice.

Later in life, Carew joined Bonnie Prince Charles’ Jacobite army but deserted as their rebellion crumbled. In 1745, he published his widely read autobiography, The Life and Times of Bampfylde Moore Carew, cementing his fame across the British Empire. However, his tales should be approached skeptically, as his memoirs are the sole source for many of his exploits. For all we know, he might have been a humble salt merchant—but that’s far less entertaining.

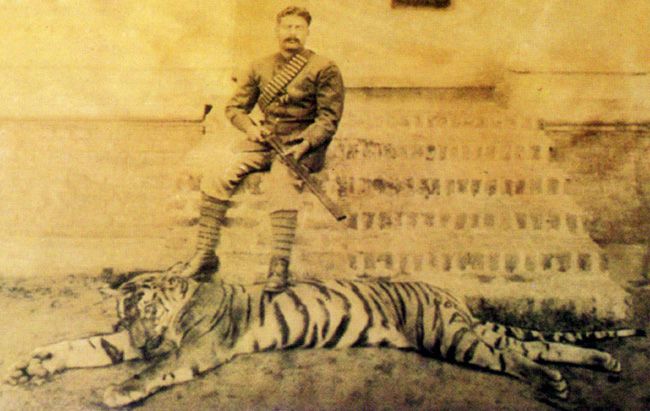

3. The Bhawal Case

In 1911, Ramendra Narayan Roy, the pleasure-seeking, tiger-hunting Prince of Bhawal, passed away under suspicious conditions. Soon after, whispers spread that he was still alive and wandering the countryside. These rumors gained traction in 1920 when a nearly naked mystic appeared and sat silently outside the Bhawal estate.

After weeks of silence, the mystic revealed himself as the long-lost prince. He claimed his cousins had tried to poison him due to his syphilis, but the attempt failed, and a sudden hailstorm interrupted his cremation. Following the failed murder, he fled and lived as a wandering ascetic, forgetting his past. Only in 1920 did he recall his true identity and return to reclaim the Bhawal estate—a tale that seemed almost too incredible to believe.

Some members of the Bhawal family accepted his story, identifying matching “marks” on his body as proof of his identity. They declared him the rightful heir and granted him a significant portion of the estate. However, skeptical relatives took legal action, leading to a 20-year court battle. Surprisingly, the imposter won in 1945, but in a twist of fate, he died while traveling to perform a ritual celebrating his unlikely victory.

2. Perkin Warbeck

Henry VII of England faced constant challenges. After defeating Lambert Simnel, who posed as the murdered Edward VI, another imposter emerged, claiming to be Edward’s brother, Richard of Shrewsbury. While it’s widely believed that both Edward and Richard were killed in the Tower of London by Richard III, the ambiguity surrounding their deaths created fertile ground for imposters.

Few should have been convinced by Perkin Warbeck’s claim to be Richard, especially since Warbeck was born in Belgium and spoke little English. However, his slight resemblance to Richard and the political motivations of Henry’s enemies led some to support his cause.

Warbeck eventually secured backing from France, Scotland, and the Holy Roman Empire—even attending the funeral of Emperor Maximilian. Despite this, Warbeck lacked leadership skills and courage. During his 1495 invasion of England, he refused to leave his ship while his troops were massacred on the shore.

Afterward, Warbeck resided in Scotland, where King James IV supported him in yet another unsuccessful invasion attempt. When this plan collapsed, he traveled to Ireland, rallying a small army. His 1499 invasion of England was swiftly crushed, and Warbeck spent his remaining days in the Tower of London, the very place where the real Richard of Shrewsbury had met his end.

1. Carlos Castaneda

Similar to Lobsang Rampa, Carlos Castaneda captivated the New Age movement with an elaborate, psychedelic narrative. In 1968, he released The Teachings of Don Juan, which chronicled his experiences with a Yaqui shaman named Don Juan. The book described Castaneda’s mystical journeys, fueled by peyote and mescaline, where he communicated with lizards, encountered the spirit Mescalito, and even transformed into animals.

However, the story had glaring inconsistencies. No one else ever encountered Don Juan, the Yaqui people do not traditionally use peyote or mescaline, and Castaneda never learned a single Yaqui word despite his claimed years of apprenticeship.

Consequently, many anthropologists labeled Castaneda a complete fraud. A revealing story recounts how a friend mentioned that neither Buddha nor Jesus wrote their own teachings—disciples recorded them, potentially altering the content. Upon hearing this, Castaneda fell silent and soon began writing The Teachings of Don Juan.

Despite these controversies, Castaneda’s career thrived—his books have sold nearly 28 million copies globally. Subsequent works expanded on his adventures with Don Juan, who eventually ascended to heaven in a fiery blaze, making it impossible for anyone to verify his existence.

Later, Castaneda established a cult centered on his Tensegrity theory. Allegedly rooted in ancient Toltec shamanism, Tensegrity included practices involving glowing eggs, spiritual exercises, and, notably, a group of women with whom Castaneda maintained close relationships.