From the archaic methods of trepanning and bloodletting to today’s advanced medical tools, surgery remains an inherently strange practice. The act of opening a human body and altering its internal structures is undeniably extraordinary. Throughout history, the field has been filled with remarkable figures, both heroic and eccentric, alongside countless unusual stories.

10. The Skull of the Beauty Queen

Jamie Hilton lived a charmed life. A devoted wife and mother, she was celebrated as one of America’s most stunning women, having won the title of Mrs. Idaho and competed in Mrs. America. However, her life took a dramatic turn in June 2012. During a fishing excursion with her husband, Hilton suffered a 4-meter (12 ft) fall, striking her head on a rock.

Upon arriving at the hospital, Hilton’s brain was swelling dangerously. To alleviate the pressure, surgeons removed 25 percent of her skull. Not wanting to discard such valuable bone, they planned to reattach it once her brain healed. But the question remained: where would they store the skull fragment in the interim?

The solution was straightforward. They stitched it into her abdomen.

By embedding the skull fragment beneath her skin, doctors aimed to preserve the tissue’s vitality. Meanwhile, Jamie wore a protective helmet to shield her head from additional injury. After 42 days, surgeons reopened her abdomen, accessed her skull, and reattached the bone securely.

Jamie appears to be thriving. In her latest blog update, she describes her scar as a “blessing” and a testament to her resilience and survival.

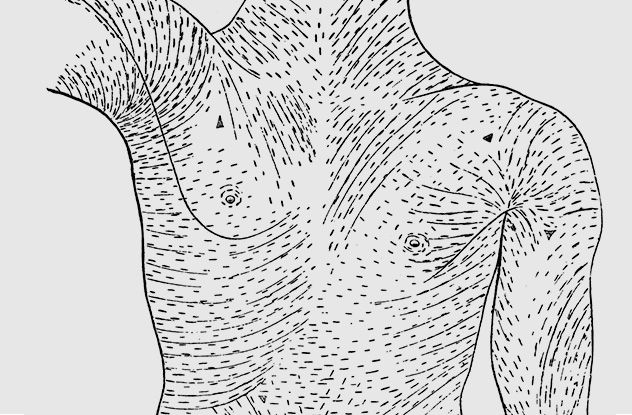

9. Karl Langer’s Ice Pick

Karl Langer, a 19th-century anatomy professor from Vienna, had an unusual habit of puncturing cadavers with ice picks. However, his actions weren’t driven by perversion (as far as records show). Instead, he was conducting groundbreaking research that required meticulously piercing deceased bodies.

As an anatomy instructor, Langer frequently worked with recently deceased subjects. During his experiments, he observed something peculiar: whenever he pierced a corpse, the resulting wound wasn’t circular but oval-shaped, despite the ice pick having a rounded tip.

The phenomenon was linked to collagen fibers, the components that give skin its elasticity. Due to collagen, some areas of the body are more flexible than others, while certain regions remain tightly bound. When Langer punctured these tense areas, the skin’s tension caused the wounds to stretch open. This posed a significant challenge for surgical patients, as incisions in these high-tension zones struggled to heal properly.

Driven to identify the safest areas for surgical incisions, Langer conducted extensive experiments on numerous cadavers. Using his ice pick, he meticulously mapped the skin’s behavior. His findings culminated in an anatomical guide, highlighting optimal and risky areas for surgical cuts. These guidelines, known as “Langer’s lines,” remain a valuable resource in modern medicine.

While contemporary surgeons avoid using Langer’s lines for areas like the forehead, they are highly beneficial in cosmetic procedures such as breast surgeries. Although many doctors now prefer cutting along natural wrinkles, Langer’s pioneering work has saved countless patients from enduring prolonged and painful recoveries.

8. Orlan’s Surgical Art

We’ve explored some eccentric performance artists before, but none come close to the sheer, stomach-churning audacity of Orlan. Born Mireille Suzanne Francette Port, Orlan has experimented with various art forms, including photography and sculpture. However, her most infamous work is “The Reincarnation of Saint Orlan,” a provocative project blending music, poetry, and cosmetic surgery.

From 1990 to 1995, Orlan underwent nine surgical procedures. Each operation was a spectacle: she entered the operating room in elaborate outfits, accompanied by music and surgeons in robes who danced around her. As mimes performed nearby, Orlan recited poetry and philosophical texts. Then, the scalpels would begin their work.

Orlan transformed herself into a living collage of iconic artworks, a fusion of Western art’s masterpieces. Surgeons sculpted her forehead to mimic the Mona Lisa and reshaped her jaw to resemble Botticelli’s Venus. In a particularly bizarre twist, she had silicone implants added above her eyebrows to create horn-like protrusions. These surgeries were broadcast live in art galleries, with Orlan remaining fully conscious throughout.

Orlan described her “carnal art” as a critique of societal beauty standards, a defiance of Christian ideals, and an endeavor to become the “ultimate artwork.” Financial motives also played a role; she sold postcards, photos, and even preserved tissue from her procedures. In a notable gesture, she once gifted Madonna a piece of her thigh.

7. India’s Kidney Kingpin

Amit Kumar was a notorious figure in the illegal kidney trade. Desperate patients seeking transplants were drawn to his clinic in Gurgaon, India, where he harvested organs from vulnerable laborers. Dubbed “Dr. Horror” by the media, Kumar employed deceit, threats, and bribes to amass a shocking number of kidneys.

Kumar launched his operation in the 1980s, prior to India’s 1994 ban on organ trading. He enlisted cab drivers to scout for foreign clients in need of kidneys, while another team targeted slum dwellers, such as beggars and cart pullers. These intermediaries offered $300–$1,000 for a kidney—a paltry sum for a vital organ, but a fortune to those living in poverty.

Exploiting the impoverished, Kumar conducted hundreds of illegal surgeries over two decades. Despite occasional arrests, he would simply relocate to a new city and resume his operations upon release. He collaborated with licensed surgeons and bribed officials to maintain his scheme. The most shocking fact? Kumar wasn’t even a real doctor.

Kumar wasn’t a trained surgeon but an ayurvedic practitioner, specializing in traditional Indian medicine. This meant he lacked the qualifications to perform even minor procedures, let alone kidney removals. Three Turkish patients died under his care, but Kumar, a master manipulator, had a licensed doctor forge death certificates attributing their deaths to heart failure.

Kumar’s empire crumbled in 2008 when a whistleblower exposed him. The informant, likely a disgruntled former associate, claimed to be a victim of Kumar’s scheme. As a result, Kumar was sentenced to 10 years for the deaths of his Turkish patients and an additional seven years for conspiracy, forgery, and intimidation.

6. The Man Who Cashed A Check

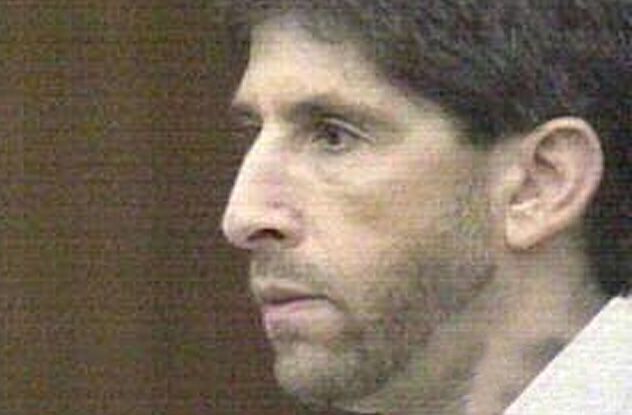

David Arndt was a renowned surgeon, celebrated for his success, charm, and intellect. A Harvard-trained orthopedic specialist, he was at the peak of his career around the turn of the millennium. However, in 2002, his career took a bizarre turn during a scheduled spinal surgery for patient Charles Algeri.

Arndt arrived at the hospital disheveled, unshaven, and with dark circles under his eyes. His behavior during the surgery was equally odd. He repeatedly asked the circulating nurse to contact his secretary to check if “Bob” had arrived—a code word for his paycheck.

When the check was finally delivered to the operating room, Arndt’s behavior became erratic. Seven hours into the procedure, with Algeri unconscious and his back still open, Arndt announced he was stepping out briefly. Instead of taking a short break, he left the hospital entirely, spending 35 minutes at the bank to cash his check.

Arndt later explained that he needed to cash the check to pay bills. This explanation did not satisfy the medical board, which subsequently suspended his license.

Some believe Arndt was a narcissist who prioritized his own needs over his patients’. Others speculate he was addicted to methamphetamine. To fund his drug habit, he even sold meth, leading to his arrest in 2003. This wasn’t his first legal issue; he had previously been arrested for drugging and sexually assaulting a 15-year-old boy.

Arndt was sentenced to 10 years in prison for his crimes. Meanwhile, Charles Algeri, his patient, suffered severe complications, requiring two additional surgeries. By 2010, Algeri had lost sensation below his right knee. He filed a lawsuit and was awarded $1.25 million in damages.

5. The Surgery That Made A Monster

In 2013, RadioLab interviewed Kevin, an epileptic who underwent brain surgery to stop his seizures. Doctors removed a portion of his brain, and initially, the procedure appeared successful. However, after Kevin turned 35, the seizures returned.

Kevin initially tried to manage the seizures, but they worsened, prompting him to schedule a second surgery. Concerned about the potential impact on Kevin’s love for music, doctors proposed an unconventional approach. As a music enthusiast, Kevin chose to remain awake and sing during the operation. Surgeons monitored his brain activity, avoiding areas that caused him to stop singing.

Following the surgery, Kevin’s seizures ceased, but his personality underwent a dramatic transformation. He began playing the piano incessantly, overeating, and exhibiting an insatiable sexual appetite. His behavior worsened when he started using his computer.

Kevin developed an addiction to pornography, ranging from bondage to bestiality and eventually child exploitation. “I didn’t want to do it,” he confessed to RadioLab, yet he continued downloading disturbing content. In 2006, authorities arrested him, leading to his imprisonment.

Kevin admitted guilt, but during sentencing, neurologist Orrin Devinsky argued that Kevin was not responsible. He was diagnosed with Kluver-Blucy syndrome, a condition caused by damage to his anterior temporal lobes—the brain region that suppresses primal urges.

Prosecutors contended that Kevin had control over his actions, citing the absence of pornographic material on his work computer. Devinsky countered that individuals with neurological disorders like Kluver-Blucy can manage their impulses when mentally engaged but lose control during periods of boredom or stress.

The judge acknowledged Kevin’s condition but ruled that he should have sought help during moments of clarity. Kevin was sentenced to 26 months in prison and 25 months of house arrest.

Today, Kevin is no longer incarcerated. He uses medication to manage his impulses and appears genuinely remorseful. However, questions remain about his culpability. Was he truly responsible for his actions, or was it a case of his brain compelling him to act?

4. William T.G. Morton Saves The Day

In the early 19th century, operating rooms resembled scenes of torture. Anesthesia had yet to be discovered, and patients were restrained by burly men or leather straps as surgeons wielded their instruments. Many survivors recalled the harrowing sounds of bones being sawed and limbs dropping to the floor.

To illustrate the horrors, consider Fanny Burney’s account of her 1811 mastectomy. She wrote, “When the dreadful steel pierced my breast, slicing through veins, arteries, flesh, and nerves... I let out a scream that lasted the entire incision—and I almost marvel that it doesn’t still echo in my ears!”

In 1846, dentist William T.G. Morton revolutionized medicine by introducing diethyl ether as an anesthetic. Convinced it could alleviate suffering, he tested the gas on his dog, patients, caterpillars, chickens, and even his pet goldfish. He even experimented on himself to ensure its safety.

Confident in ether’s potential, Morton approached John Warren, a renowned surgeon at Massachusetts General Hospital. Despite Warren’s skepticism, he allowed Morton to demonstrate the gas on October 16. The procedure took place in the Ether Dome, an amphitheater filled with doubtful doctors and curious students. The patient, Edward Abbott, had a neck tumor.

As Morton prepared his untested homemade inhaler, Dr. Warren remarked sarcastically, “Well, sir, your patient is ready.” Morton administered the ether, and within four minutes, Abbott was unconscious. Morton turned to Warren and said, “Your patient, sir.”

The surgery proceeded flawlessly. Warren removed the tumor without any resistance or cries of pain from Abbott. Upon waking, Abbott described only a mild scraping sensation, with no recollection of pain.

Morton’s breakthrough quickly gained global attention, and ether became widely adopted in surgeries. Operating rooms, once filled with screams, became significantly quieter.

3. The Surgeon Who Gave Old Men Monkey Balls

Serge Abrahamovitch Voronoff was an eccentric figure. A Russian surgeon trained under a Nobel Prize–winning physician, he researched the effects of castration on eunuchs while serving the Egyptian king until 1910. Fascinated by testicles, Voronoff believed they held the key to reversing aging. Upon returning to Paris, he began offering “monkey gland transplants” to elderly men seeking to restore their mental sharpness and sexual vigor.

The first step in the procedure was acquiring monkey testicles. Voronoff often used baboons and chimpanzees (technically apes), and the process was meticulous. The animals were anesthetized and placed in a specialized box to keep them immobilized during the extraction. After all, no one wanted an enraged chimp waking up mid-surgery.

Voronoff then sliced the testes into thin sections and grafted them onto the patients’ genital areas. Despite its oddity, the procedure gained immense popularity, and by the 1930s, thousands of men had undergone the treatment.

Voronoff amassed considerable wealth from his procedures. He resided in one of Paris’s most luxurious hotels and even established a facility dedicated to breeding potential “donors.” However, over time, the scientific community dismissed Voronoff as a fraud. Monkey gland transplants were ineffective and provided no real benefits. Some even speculate that these surgeries may have contributed to the transmission of AIDS from monkeys to humans, though this claim remains controversial. Regardless, Voronoff’s methods were undeniably bizarre.

2. Ex Vivo Surgeries

Heather McNamara, a seven-year-old from Long Island, New York, was battling an aggressive form of cancer. Her tumor was no ordinary growth—it had entwined itself around her blood vessels and engulfed her intestines, stomach, spleen, pancreas, colon, and liver. Traditional surgical removal was impossible.

Enter Dr. Tomoaki Kato, a Japanese surgeon practicing in America, who specializes in “ex vivo” resection—a procedure meaning “outside the living body.” Instead of operating internally, Kato removes the affected organs and performs surgery externally. This high-risk approach is reserved for extreme cases like Heather’s.

By the time Kato finished removing Heather’s organs, only the left side of her colon remained untouched by the tumor. The rest of her organs were preserved in a chilled solution. The procedure required meticulously cutting and sealing countless blood vessels. Three surgical teams worked swiftly to clean the organs, as Heather’s circulatory system would fail if her organs remained outside her body for more than six hours.

The entire surgery, from the initial incision to the final stitch, lasted 23 hours. This included replacing damaged blood vessels, using a section of Heather’s jugular vein to reconnect her liver, and attaching her esophagus directly to her intestines since her stomach was beyond repair. Dr. Kato took a few short breaks during the marathon procedure.

Dr. Kato has performed numerous “ex vivo” surgeries, most with positive outcomes. However, there are instances where the damage is too extensive. In 2010, Kato attempted to save Robert Collison, a 59-year-old man with a 5-kilogram (10 lb) tumor. While the surgery itself was successful, Collison passed away eight weeks later. Thankfully, Heather McNamara’s story had a happier ending—she survived the operation and, as seen in the video above, is thriving.

1. TheNoseDoctor

Mark Weinberger, known as “TheNoseDoctor,” built a thriving practice in Merrillville, Indiana, a town surrounded by steel mills. The polluted air brought in countless patients suffering from sinus issues, and Weinberger had a one-size-fits-all solution: surgery. Surgery for everyone.

During their first visit, 90 percent of Weinberger’s patients were told they needed sinus surgery. Even those with minor sniffles left with holes drilled into their maxillary sinuses. Most of these procedures were unnecessary, and his outdated techniques often led to severe infections.

Weinberger’s actions went beyond negligence—he displayed psychopathic tendencies. He terrified patients with fabricated images of grotesque, bloody polyps in their sinuses. With no other surgeons in his practice and his own CAT scan machine, Weinberger maintained complete control, ensuring patients never sought second opinions.

Before his downfall, Weinberger amassed $30 million, owning a 25-meter (80 ft) yacht, Bahamian properties, and a lavish five-story Chicago home. While he lived extravagantly, his patients suffered. He overlooked a tumor in a nine-year-old girl’s pituitary gland and ignored a woman’s throat cancer, which proved fatal.

As malpractice lawsuits piled up, Weinberger fled. After embezzling millions and stocking up on camping gear, he abandoned his wife in Greece, leaving her with $6 million in debt. He hid in northwestern Italy for five years until his girlfriend uncovered his identity and turned him in.

Even in his final act of incompetence, Weinberger attempted to cut his own throat but failed. Rather than ending his life, he was sentenced to seven years in prison. In 2013, his 282 victims received a $55 million settlement as compensation.