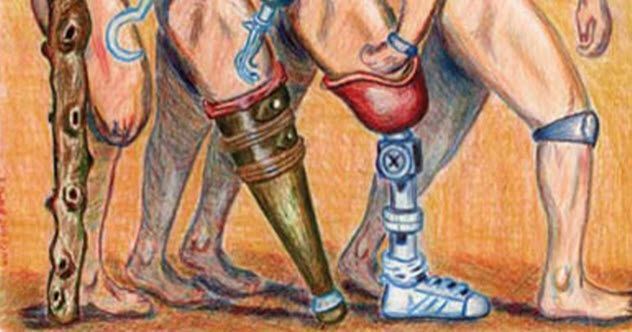

The first prosthetics were simple and rudimentary. From peg legs to hook hands, these early devices enabled individuals to carry out the essential tasks of their professions. Throughout history, prosthetics have undergone significant advancements in materials and design. This evolution might make the 10 antique body parts featured in our list seem even more strange and fascinating than they would have appeared in their time.

10. Artificial Eyeball

Shahr-e Sukhteh, an ancient Bronze Age settlement in southeastern Iran, revealed a delicate 2.5-centimeter (1 in) prosthetic eye made from bitumen paste with a thin gold layer on top. Shaped like a hemisphere, it featured holes on either side to secure it in place on the eye socket with gold wire.

The central part of the prosthetic eye was intricately etched with an iris and golden rays representing the Sun. The remains found alongside the eye date back to 2900 to 2800 BC. Standing at 1.8 meters (6 ft), the exceptionally tall woman was likely of royal or noble lineage.

In the fifth century BC, Egyptian priests created early prosthetic eyes called ectblepharons, made from painted clay or enameled metal, which were attached to fabric and worn outside the eye socket.

9. Artificial Toes

Archaeologists have discovered two prosthetic toes. One, the Greville Chester toe, dates back to 600 BC and is currently housed in the British Museum. Crafted from cartonnage (ancient papier-mâché) combined with linen, animal glue, and tinted plaster, this prosthetic big toe helped its wearer walk.

An even older prosthetic big toe, the Cairo toe, found near Luxor, Egypt, and now on display at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, dates from 950 to 710 BC. Made from wood and leather, it resembles a gaiter but only covers the instep. Studies show that when worn with sandals, it restored 60–87 percent of the flexion of the original left toe.

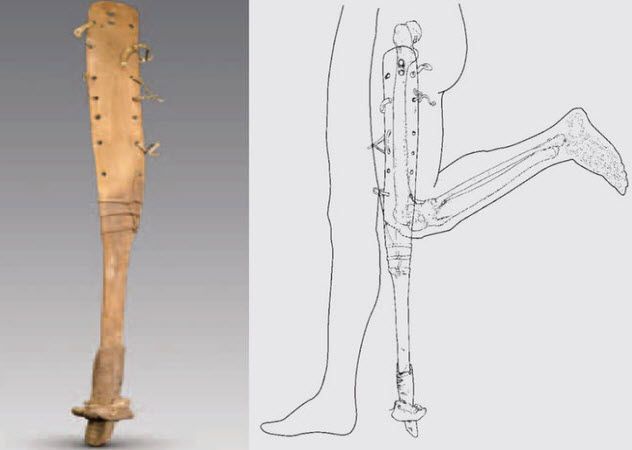

8. Prosthetic Leg

Unearthed in 2016 from a grave in Turpan, China, the 2,200-year-old remains of a 50- to 65-year-old Gushi man, standing at 170 centimeters (5'7"), included a prosthetic leg. Crafted from poplar, the leg featured holes along both sides, allowing it to be attached to the deformed limb with leather straps.

The prosthesis was fitted with a horse's hoof instead of a foot. The man’s kneecap, thighbone, and tibia had fused at an 80-degree angle, likely due to joint inflammation, rheumatism, or injury. However, it is more probable that tuberculosis caused the deformity by inducing a 'bony growth' that fused the joint.

An earlier prosthetic limb, dating back to 300 BC, was discovered in 1858 in Capua, Italy. Made from bronze and iron surrounding a wooden core, this leg was destroyed in 1941 during an air raid on London.

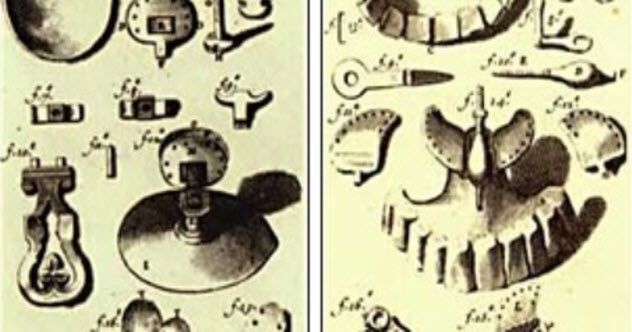

7. Prosthetic Lip and Palate

It is believed that the renowned Greek orator Demosthenes (384–322 BC) may have used pebbles to fill a congenital cleft lip and palate. Since then, various obturators have been created for different purposes. In the mid-18th century, one such device was inserted into the palatal defect, followed by mechanical wings that would contact the palate's superior surface through a turnkey mechanism operated by the wearer.

The late 18th century saw the development of obturators similar to modern designs. One of these was inflated with water to fill a maxillary defect. In 1893, President Grover Cleveland (1837–1908) was fitted with a vulcanite obturator to close a defect caused by the surgical removal of a malignant maxillary tumor.

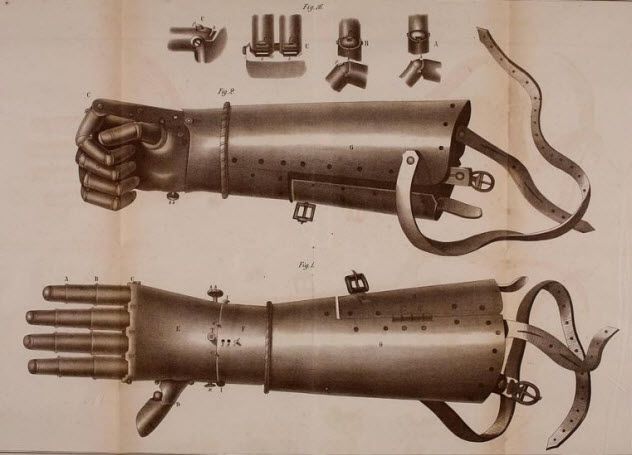

6. Prosthetic Arm

Pliny the Elder (AD 23-79) mentioned a prosthetic right arm created for a general so he could hold his shield in battle during the Second Punic War (218–200 BC). However, it wasn't until the early 1500s that artificial arms began to include detailed features like 'nail beds and knuckles of [the] hand.' This was exemplified by an iron prosthetic arm made for 24-year-old Gottfried von Berlichingen (1480–1562), who lost his arm to a cannonball during the siege of Landshut in 1504.

Gottfried's prosthetic arm was fastened with leather straps at the end. Its articulated fingers were capable of moving and spreading apart, and the hand could close into a fist. Although the arm was likely heavy, its increased joint mobility was a significant advancement over previous prosthetic limbs.

5. Prosthetic Tooth

The 1,600-year-old skull of a 30- to 45-year-old woman from an upper-class background, discovered in Teotihuacan (50 kilometers (30 mi) north of Mexico City), reveals prosthetic dental work. Her upper front teeth are covered with 'two round pyrite stones,' a feature typically found in the Mayan regions of southern Mexico and Central America. This suggests she was a foreigner, not a native of Mexico. Additionally, her lower jaw contains an artificial tooth crafted from serpentine.

4. Prosthetic Foot

The ancient Greek historian Herodotus (484–425 BC) documented one of the earliest recorded prosthetic feet. A 'Persian seer,' condemned to death, escaped by severing his own foot and replacing it with 'a wooden filler,' enabling him to walk 50 kilometers (30 mi) to the nearest town.

In most cases, prosthetic feet were part of a complete artificial leg, as the nature of amputations often prevented the isolated replacement of just the foot. This changed in 1843 when Sir James Syme (1799–1870) 'discovered a new method of ankle amputation that did not involve amputation at the thigh.' This advancement meant that amputees could recover the ability to walk using just a prosthetic foot instead of a full leg prosthesis.

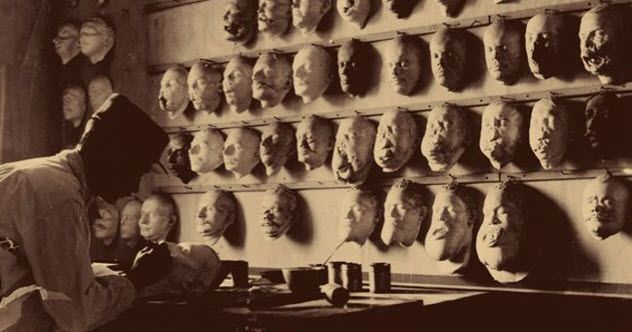

3. Prosthetic Face (1916)

Prosthetic faces emerged after World War I when artists and sculptors from the 3rd London General Hospital’s Masks for Facial Disfigurement Department 'crafted lifelike masks' for soldiers who had been disfigured or severely injured during combat.

Francis Derwent Wood (1871–1926), the program's founder, used his artistic talents to create lightweight masks that featured personalized prewar portraits of the injured soldiers. While the masks were visually significant, they also provided psychological benefits by helping restore the men’s independence, self-respect, confidence, and pride in their appearance.

2. Prosthetic Nose

A brass nose attached to a pair of eyeglasses and mounted on a metal loop that fit over the head served as a prosthesis for a 19th-century woman suffering from syphilis who had lost her nose to the disease’s effects.

Over 300 years before this, the Dutch astronomer Tycho Brahe (1546–1601) lost his nose in a duel in 1566. For the rest of his life, he wore a brass prosthetic nose, which, while noticeable up close, effectively covered the gap in the bridge of his nose.

1. Prosthetic Hand

In the late 16th century, a unique prosthetic hand was crafted in Germany. Made of iron, it included detailed fingernails and knuckle wrinkles, fitting securely over a metal frame that slipped onto the forearm.

During the latter part of the 1800s, Victorian prosthetic hands were created from metal. These hands, while flat and ornamental, featured articulated thumbs and fingers, allowing movement. Some even allowed limited wrist movement.

Prosthetic hands were often attached to an armature, which connected to a sleeve that slid over the arm or stump. For instance, a 16-year-old girl had a prosthetic hand made of “wood, leather, and textile,” with wooden joints that enabled the fingers to curl or stretch.