The Colossus of Rhodes, Mytour-style

© 2007 Mytour

The Colossus of Rhodes, Mytour-style

© 2007 MytourWhat links the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World? Primarily, their immense scale left travelers and scholars in awe. Take the Colossus of Rhodes, a 110-foot (3-meter) bronze titan overlooking the Mediterranean until an earthquake toppled it. Similarly, the Great Pyramid of Giza, specifically Khufu, held the title of the tallest structure on Earth for four millennia.

Today’s engineers continue to push boundaries with colossal projects. Consider the Three Gorges Dam, a massive hydroelectric facility stretching across China’s Yangtze River, or the Burj Khalifa, Dubai’s record-breaking skyscraper piercing the sky. These feats exemplify modern engineering ambition.

Some creators, however, seek to astonish in unconventional ways. These visionary architects and designers craft surreal structures that range from mildly eccentric to utterly bizarre. While their creations may not dominate the skyline, their mind-bending, gravity-defying designs are guaranteed to leave you speechless and spark countless exclamations of amazement.

We’ve curated a list of 10 extraordinary engineering feats for you. First on the list is a tower that puts the Leaning Tower of Pisa to shame, making it appear perfectly upright in comparison.

10: Capital Gate

Yes, you read that correctly. Its lean is entirely intentional.

© Jumana El Heloueh/Reuters/Corbis

Yes, you read that correctly. Its lean is entirely intentional.

© Jumana El Heloueh/Reuters/CorbisMost engineers strive to keep their skyscrapers perfectly vertical. A leaning building typically signals a design flaw. Take the Leaning Tower of Pisa, for instance, which tilts nearly four degrees due to its unstable foundation on weak soil.

However, some daring engineers deliberately design their structures to lean. Enter Capital Gate, a 35-story skyscraper in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. This architectural wonder leans an astonishing 18 degrees westward—over four times more than the Leaning Tower of Pisa. Achieving this required 490 piles drilled nearly 100 feet (30 meters) deep and a robust foundation of reinforced steel. The building’s unique curvature comes from its pre-cambered core, a steel-reinforced concrete spine with a deliberate curve. Each diamond-shaped panel had to be custom-cut to fit its specific angle, adding to the complexity of this gravity-defying project.

In 2010, Capital Gate earned the Guinness World Record for being the Farthest Man-made Leaning Building. It’s important to note that this title differs from the Farthest Man-made Leaning Tower, as the latter lacks functional floor space.

9: Laerdal Tunnel

The illumination of Laerdal

iStock/Thinkstock

The illumination of Laerdal

iStock/ThinkstockHighway engineers faced a significant challenge when linking the Norwegian towns of Laerdal and Aurland: the imposing Hornsnipa and Jeronnosi mountains. Rather than navigating around these natural barriers, they chose to bore straight through them. This ambitious project resulted in the Laerdal Tunnel, a 15-mile (24-kilometer) passage carved through solid gneiss rock, securing its place as the world’s longest operational road tunnel.

Digging such a lengthy tunnel was only part of the challenge. Designers also had to ensure drivers could traverse the underground route without falling victim to highway hypnosis. To combat this, the Norwegian Public Roads Administration consulted psychologists to create an engaging driving experience. Their recommendations included installing blue lighting and incorporating gentle curves to maintain driver alertness. Additionally, the tunnel was divided into four distinct sections to break up the monotony and keep motorists focused.

Drivers passing through the Laerdal Tunnel today may not immediately notice its thoughtful design features, but they’ll undoubtedly feel their benefits as they complete the 20-minute journey and emerge safely into daylight after traveling through the heart of a mountain.

8: Die Gläserne Manufaktur

A factory becomes truly unique when the New York Philharmonic chooses to perform there. During their rendition of 'Kraft,' the orchestra creatively used original VW Phaeton car parts as percussion instruments.

© Fabrizio Bensch/Reuters/Corbis

A factory becomes truly unique when the New York Philharmonic chooses to perform there. During their rendition of 'Kraft,' the orchestra creatively used original VW Phaeton car parts as percussion instruments.

© Fabrizio Bensch/Reuters/CorbisFactories are often imagined as dull, industrial structures with smokestacks spewing pollution. However, in 2001, Volkswagen revolutionized this image with the opening of Die Gläserne Manufaktur—'the factory made of glass'—dedicated to producing the Phaeton luxury sedan. Located in the heart of Dresden, Germany, within the Great Garden, this facility challenged urban planners who believed manufacturing couldn’t coexist with urban culture and residential areas.

Die Gläserne Manufaktur is far from a typical industrial complex. Absent are smokestacks, deafening noises, or harmful emissions. Instead, the factory boasts 290,000 square feet (26,942 square meters) of glass walls, offering the public a transparent view of its operations [source: Markus]. Visitors might marvel at the Canadian maple floors or the opera house-like lobby, but the real spectacle lies in watching Phaeton components glide along conveyor belts, ready for assembly by robots and 227 skilled workers [source: Markus].

This could very well represent the factory of tomorrow—or simply a bold statement of corporate openness.

7: Kansas City Public Library Parking Garage

Looking for a good book recommendation? Find inspiration in the parking garage of Kansas City’s Central Library.

John Dillon/Flickr Vision/Getty Images

Looking for a good book recommendation? Find inspiration in the parking garage of Kansas City’s Central Library.

John Dillon/Flickr Vision/Getty ImagesIf you attempted to read the giant replica of "To Kill a Mockingbird" on the Community Bookshelf outside Kansas City’s Central Library, you’d experience both disappointment and delight. The spine of this massive book spans 25 feet by 9 feet (7.6 meters by 2.7 meters), but it doesn’t contain actual pages. Instead, it’s part of a creative facade featuring 22 literary classics that disguises the library’s parking garage. Rather than concealing the garage behind the main building or opting for a plain concrete structure, the designers chose to integrate it into the library experience when it opened in 2004.

The community played a key role in this project. Residents of Kansas City proposed titles for the bookshelf, and the library’s board of trustees curated the final selection of 22 works, including fiction, nonfiction, poetry, and two books dedicated to Kansas City’s history. Alongside Harper Lee’s classic, you’ll find Joseph Heller’s "Catch-22," Ray Bradbury’s "Fahrenheit 451," Rachel Carson’s "Silent Spring," Ralph Ellison’s "Invisible Man," Charles Dickens’ "A Tale of Two Cities," and E.B. White’s "Charlotte’s Web." These literary giants now stand in a physical form as monumental as their cultural impact.

6: Large Zenith Telescope

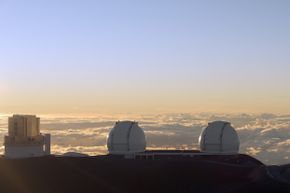

The Subaru Telescope and the W. M. Keck Observatory’s Twin Telescopes gaze into the cosmos from their elevated position above the clouds on Hawaii’s Mauna Kea. In the future, we might even place a telescope on the moon.

© Ed Darack/Science Faction/Corbis

The Subaru Telescope and the W. M. Keck Observatory’s Twin Telescopes gaze into the cosmos from their elevated position above the clouds on Hawaii’s Mauna Kea. In the future, we might even place a telescope on the moon.

© Ed Darack/Science Faction/CorbisOptical telescopes, which provide groundbreaking views of stars, nebulae, and exoplanets, demand engineering brilliance comparable to that of dams, tunnels, and bridges. For instance, the Subaru Telescope, located atop Mauna Kea in Hawaii, features a primary mirror with a 27-foot (8.2-meter) diameter and weighs over 25 tons. The supporting structure and the enclosure housing the system are as intricate as any modern building.

Traditional telescopes face significant challenges, such as transporting fragile mirrors to mountain summits and continuously adjusting for distortions caused by gravity, humidity, and other environmental factors. Liquid mirror telescopes, like the University of British Columbia’s Large Zenith Telescope (LZT), solve these issues. The LZT employs liquid mercury as its primary mirror, which can be poured on-site and maintains a flawless parabolic shape when rotated steadily. It reflects up to 75 percent of incoming starlight at roughly one-fifth the cost of a conventional optical telescope [source: Dorminey].

Currently, the LZT is the world’s largest mercury-based spinning telescope, boasting a 6-meter (20-foot) aperture. However, India, Belgium, and Canada are collaborating to construct an even larger version—the International Liquid Mirror Telescope—which will observe the stars from Devasthal Peak in northern India.

5: Palm Jumeirah

A bird’s-eye view of The Palm Jumeirah in Dubai, captured on Aug. 31, 2012.

© Jumana el Heloueh/Reuters/Corbis

A bird’s-eye view of The Palm Jumeirah in Dubai, captured on Aug. 31, 2012.

© Jumana el Heloueh/Reuters/CorbisDubai has undergone extraordinary growth over the past decade, primarily along its 37-mile (60-kilometer) Persian Gulf coastline. However, the dense concentration of high-rise apartments, skyscrapers, and hotels has left little space for further development. To address this, Nakheel Properties, a government-supported real estate developer, embarked on an ambitious project to extend the shoreline by constructing three artificial islands called the Palm Islands.

How is such a monumental task achieved? By amassing vast quantities of sand and rock to form an island in the ocean. To build Palm Jumeirah, the first of the three islands, workers dredged over 3 billion cubic feet of sand [source: Dowdey]. Rather than creating a simple mound, they designed an archipelago shaped like a palm tree, complete with a 1.24-mile (2-kilometer) trunk, 16 fronds forming the crown, and a surrounding crescent. GPS technology ensured the structure maintained its precise symmetry throughout the construction process.

As of 2013, Palm Jumeirah remains the world’s largest man-made island, though its counterparts are set to surpass it. Once completed, Palm Deira will be even more expansive, covering approximately 18 square miles (47 square kilometers) of land reclaimed from the Persian Gulf.

4: Melbourne Rectangular Stadium (AAMI Park)

The Melbourne Rectangular Stadium, inspired by Buckminster Fuller, is photographed on April 26, 2011.

© Ben Hosking/Arcaid/Corbis

The Melbourne Rectangular Stadium, inspired by Buckminster Fuller, is photographed on April 26, 2011.

© Ben Hosking/Arcaid/CorbisDespite its straightforward name, the Melbourne Rectangular Stadium, known as AAMI Park in Australia, is anything but ordinary. From above, its innovative design has been celebrated as the "next generation of sports stadia" [source: The Institution of Structural Engineers]. The standout feature is its roof, inspired by the geodesic domes of R. Buckminster Fuller. These domes are constructed from interlocking polygons, creating a spherical structure that is both strong and resource-efficient compared to traditional methods.

AAMI Park’s roof consists of multiple geodesic domes, resembling a complex soap-bubble surface. Remarkably, the stadium uses 50 percent less steel than conventional cantilever designs [source: Major Projects Victoria]. It also incorporates significant recycled building material, harvests rainwater from the roof, and employs an advanced automation system to reduce energy consumption. Upon its opening in May 2010, it garnered numerous awards for architectural innovation, structural engineering, and sustainable construction. However, the cheers you’ll hear are from over 30,000 fans supporting local soccer and rugby teams, not environmentalists.

3: Erion Globe

Globe Arena, also known as Erion Globe, holds the title of the world’s largest spherical building.

© Claudio Cassaro/Grand Tour/Grand Tour/Corbis

Globe Arena, also known as Erion Globe, holds the title of the world’s largest spherical building.

© Claudio Cassaro/Grand Tour/Grand Tour/CorbisThe Erion Globe, a sports arena in Stockholm, boasts several impressive records. With a diameter of 361 feet (110 meters), an internal height of 279 feet (85 meters), and a volume of 21,188,800 cubic feet (600,000 cubic meters), it is the largest spherical structure globally. Remarkably, its construction was completed in just 2.5 years, with work beginning on Sept. 10, 1986, and the venue opening on Feb. 19, 1989.

Beyond hosting hockey matches and live events, the Erion Globe plays a unique role in the world’s largest educational model. Stockholm University’s astronomy department used the Globe to represent the sun in a scaled model of our solar system at a ratio of 1:20,000,000. The inner planets are located within Stockholm, while the outer planets are spread across northern Sweden. For instance, Neptune is positioned in Söderhamn, 153 miles (246 kilometers) away, and the dwarf planet Pluto is in Delsbo, 186 miles (300 kilometers) distant. Each model planet is hosted by an institution, allowing visitors to explore the solar system without leaving Earth.

2: China Central TV Headquarters

A photo of the CCTV (China Central Television) building under construction in 2008. The unique design was created by principal architects Rem Koolhaas and Ole Scheeren.

© Tom Fox/Dallas Morning News/Corbis

A photo of the CCTV (China Central Television) building under construction in 2008. The unique design was created by principal architects Rem Koolhaas and Ole Scheeren.

© Tom Fox/Dallas Morning News/CorbisAt first glance, the China Central TV (CCTV) headquarters resembles something from an M.C. Escher artwork. However, this is no illusion of endless loops or staircases. Completed in 2012 after a decade of design and challenges—including a 2009 fire in a nearby CCTV building—the structure has become a defining feature of Beijing. Alongside the Bird’s Nest and the Water Cube, iconic venues from the 2008 Olympics, it symbolizes China’s rise as a global superpower.

Designed by the Dutch firm OMA, the building reimagines the traditional skyscraper by creating a three-dimensional loop. Two leaning towers, one 54 stories and 768 feet (234 meters) tall, and the other 44 stories and 689 feet (210 meters) tall, are connected by L-shaped sections. The design includes a cantilever that extends 246 feet (75 meters) west and 220 feet (67 meters) south, defying conventional architectural norms.

As stated on the OMA Web site, the architects took inspiration from the interconnected nature of television production. While this may sound whimsical, the result is a structure that is anything but ordinary—a bold departure from traditional skyscrapers.

1: Rolling Bridge

In this Aug. 1, 2006 photo, the Rolling Bridge appears unremarkable. However, when a boat needs to pass, it transforms into a stunning three-dimensional octagon, showcasing its unique engineering.

View Pictures/UIG via Getty Images

In this Aug. 1, 2006 photo, the Rolling Bridge appears unremarkable. However, when a boat needs to pass, it transforms into a stunning three-dimensional octagon, showcasing its unique engineering.

View Pictures/UIG via Getty ImagesEngineers don’t always need grand scale to leave a lasting impression. The Rolling Bridge, spanning just 39 feet (11.8 meters) over London’s Grand Union Canal, proves this with its ingenious design. Composed of eight timber-and-steel sections connected by hinges, it lies flat when fully extended. Using hydraulic pistons, the sections lift and pivot, allowing the bridge to curl into a compact form, reminiscent of a pill bug rolling up. While boats navigate the canal, the bridge rests on the bank, resembling a piece of modern art.

The Rolling Bridge was conceived by Thomas Heatherwick, known for his unconventional designs like the 2012 Olympic cauldron and the B of the Bang sculpture. While Manchester removed the latter due to safety concerns, the Rolling Bridge has faced no such issues. In 2005, it earned a Structural Steel Design Award, with judges praising it as a "delightful addition to the Paddington Basin area, evoking the charm of a Leonardo da Vinci sketch when rolled up."