Cheers to National TV Dinner Day! September 10th is a day to celebrate the iconic, sometimes controversial, and ever-evolving American convenience meal.

1. THE ORIGINAL TV DINNER WAS INSPIRED BY A THANKSGIVING FEAST.

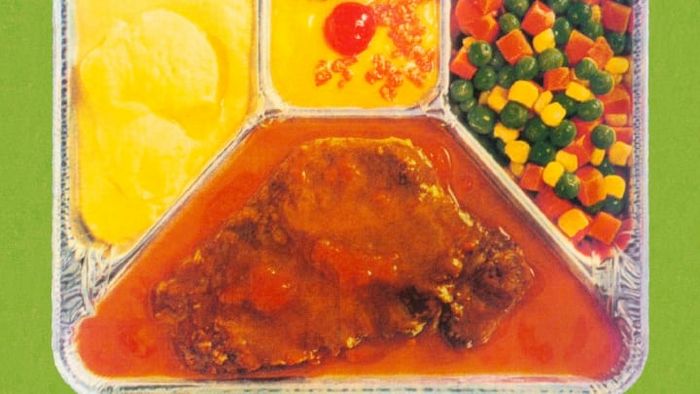

The very first TV Dinner, created by Omaha’s C.A. Swanson & Sons in 1954, was designed to mimic a Thanksgiving meal. The tray included turkey, gravy, cornbread stuffing, sweet potatoes, and buttered peas, all for 98 cents. It came in a segmented aluminum tray, covered with foil for oven heating, and packaged in a cardboard box styled like a vintage television, complete with “dials” and a “volume control knob.” That year alone, 10 million meals were sold.

2. THE QUESTION OF WHO ACTUALLY INVENTED THE TV DINNER REMAINS A SUBJECT OF DEBATE.

iStock

iStockIn a well-known 1999 Associated Press article, a former Swanson employee named Gerry Thomas modestly requested that reporter Walter Berry not call him “the father of the TV dinner.” “It bothers me,” Thomas admitted, “I didn’t invent the dinner itself. I just innovated the tray design, came up with the name, and created some unique packaging.”

The article goes on to tell an extraordinary tale that’s been repeated many times since: In the winter of 1952, Swanson found itself with 520,000 pounds of leftover Thanksgiving turkey, stored in refrigerated rail cars. Desperate to find a use for it, they turned to their employees for a solution.

During a sales trip, Thomas was at a warehouse meeting with a distributor when he noticed a metal tray. He learned that Pan Am had been testing the trays as a way to serve hot meals on long flights. “I asked if I could borrow it and slipped it into my overcoat pocket,” Thomas recalls. He then sketched a segmented design for the tray, and the idea hit him to tap into the growing television craze in American homes. His final moment of inspiration: enjoying “Thanksgiving” dinner while watching TV.

However, in 2003, the Los Angeles Times published an extensive investigation into the origins of the TV dinner, revealing that several Swanson heirs, some journalists who had written about the topic, and former Swanson employees disagreed with Thomas's account. They credited various parts of the TV Dinner concept to other members of the Swanson team. Nevertheless, Thomas stood by his version of events, acknowledging that he might have exaggerated or forgotten some details, but insisting that the main facts were “largely correct and accurate.” When Thomas passed away in 2005, many of the obituaries, such as this one in The Washington Post, credited him as the TV Dinner’s inventor.

The Library of Congress attributes the creation of the TV dinner to three different sources: Gerry Thomas, the Swanson Brothers, and Maxson Food Systems, Inc., which in 1945 produced “Strato-Plates,” complete frozen meals designed for airplane use, although these meals never made it to retail shelves.

3. THE NAME "TV DINNER" WAS PROBABLY THE KEY TO ITS MASSIVE SUCCESS.

In her 1994 Associated Press article titled “The Year the TV Dinner Knocked America Cold,” Kay Bartlett notes that, in 1954, television was “a new and captivating sensation, especially for children, with only three to four hours of new content each day, generally in the late afternoon and evening, right around dinner time. Families were organizing their schedules, after school and work, around television. Meal preparation was often limited.”

In essence, families moved away from gathering around the dinner table and instead circled around the TV.

Moreover, the ‘futuristic’ look of the aluminum tray may have helped boost the TV dinner’s appeal. Nutritional anthropologist Deborah Duchon explained to the Christian Science Monitor in 2004 that, “In the ‘50s, society became fascinated with the future. We speculated about life in the year 2000 and were captivated by technology and machinery. People embraced TV trays and TV dinners not because the food was good – it was awful – but because it felt futuristic and convenient.”

4. THE TV DINNER MAY HAVE PLAYED A ROLE IN THE RISE OF FEMINISM.

iStock

iStockThe National Women’s History Museum points out: “TV dinners did more than just feed families; their convenience and quick preparation time gave women (who often did most of the cooking) more personal time to pursue careers and other interests, all while still ensuring a hot meal for their families. One of the earliest ads for Swanson showed a woman pulling a Swanson dinner from her shopping bag and assuring her husband, ‘I’m late—but dinner won’t be.’” (Banquet used a similar marketing approach in a 1962 ad for their TV dinners, shown above.)

Although the TV dinner brought joy to many women, some men were less enthusiastic. In the iconic 1999 AP interview, Gerry Thomas recalled receiving complaints. “I remember getting hate mail from men who wanted their wives to cook from scratch like their mothers did,” he shared. “Women had gotten used to the freedom that men had always enjoyed.”

5. THERE’S A SEMI-RECOGNIZED “MOTHER OF THE TV DINNER”

In 1953, Betty Cronin, a recent graduate of Duchesne College, was working as a bacteriologist at Swanson when she was given the task of developing the TV Dinner. She managed a team of mostly male employees.

“I had medical students working for me,” Cronin recalled to the Chicago Tribune, who named her the ‘mother of the TV dinner’ in 1989. “They just couldn’t handle it. I was looked at like, ‘Why aren’t you in Library Science?’”

Cronin was soon promoted to director of product development and became the person who figured out how to heat the meat, vegetables, and potatoes at the same time with one cooking time. She also solved other challenges: “What kind of [fried chicken] breading would stay on through freezing, not be too greasy, and still taste good?” Cronin recalled. “That was our biggest hurdle.”

Cronin ended up taste-testing all of her own creations. After encountering many failures, she grew weary of it and enlisted the help of some other unfortunate souls. “I had friends I’d use as a test panel,” Cronin said. “I’d call them up and say, ‘Don’t cook dinner, I’m sending something over.’ Sometimes they’d say, ‘Don’t bring any more unless you bring a lot of beer, too.’”

6. THE ‘60S SAW TWO MAJOR CHANGES TO THE TV DINNER

iStock

iStockIn 1960, dessert was introduced, and that small compartment of cobbler, which would go on to burn the roofs of many mouths, made its first appearance. (But the brownie also made its debut – yum!)

In 1962, Swanson executives became concerned that the name “TV Dinner” might limit customers to eating the meals only during TV time, so it was removed from the packaging. In 1969, the company launched Swanson Breakfasts.

7. BY THE ‘70S, THE SIZE OF TV DINNERS GREW SIGNIFICANTLY.

In 1973, Swanson launched Hungry Man meals, targeting the hungry man (or, let’s be real, the hungry woman – no shame in that!) who desired a second helping. Around the same time, Banquet introduced its own version, the “Man Pleaser” dinner.

8. IN THE ‘80S, MARKETING SHIFTED AWAY FROM THE “BUSY LIFESTYLE” FOCUS OF TV DINNERS.

The ads featuring the overworked housewife that had become a point of pride for women in the ’50s and ‘60s began to fade in the ‘80s. In a 1982 New York Times article on ad research, Eric Pace reported that when Chicago ad agency Leo Burnett created a campaign for Swanson frozen dinners, they discovered that although TV dinner eaters were “harassed and hard-working,” “harassed customers didn’t want to be reminded of how chaotic their lives were.” This may explain why the ad from the ‘80s shows relaxed individuals, subtly suggesting that there’s no real difference between home-cooked meals and Swanson’s chicken dinner.

Marketing for TV dinners took a dramatic shift from its early strategies. A 2011 Adweek article compares a ‘60s-era Swanson TV dinner ad, which emphasized “futuristic” elements like the aluminum tray, with a modern Stouffer’s ad showing food “piled on an earthenware plate – neatly removed from the plastic tray it came in,” set against a farm backdrop.

9. SINCE 1987, THE TV DINNER TRAY HAS HAD A PLACE OF HONOR IN THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN HISTORY.

This is one of the original trays created for the first ’50s TV Dinner, now part of a collection of iconic pop-culture memorabilia, which includes Archie Bunker’s chair and Fonzie’s leather jacket.

As stated on the museum’s website, “The TV dinner symbolized a shift in how Americans viewed food.”

10. IN 2008, A $30 TV DINNER WAS AVAILABLE FOR PURCHASE.

In the midst of the Great Recession, you could still indulge in a $30 TV dinner at the Loews Regency Hotel in New York. As Jennifer Lee wrote in a New York Times blog post on the topic, “This is a city where even the simplest foods can be reimagined as luxury.”

So, what made this luxury TV dinner so special? According to Lee, “The trays, instead of being made from aluminum or plastic, are crafted from porcelain. The fried chicken is ‘free-range.’ The mac ‘n’ cheese is made with cheddar asiago and topped with a Parmesan crust. And the pot roast is braised in Burgundian pinot noir.”

Last year, British chef Charlie Bigham took luxury ‘ready meals’ to a whole new level. As Thrillist describes it, the meal includes “all the billionaire essentials: salmon, scallops, turbot, oysters, and lobster tails poached in Dom Perignon. White Alba truffles, Beluga caviar, and a 24-carat gold leaf crumb garnish – because, of course, parsley is for peasants.” The entire dish set you back £314, or $514.

11. THE FUTURE OF THE TV DINNER IN THE FREEZER AISLE REMAINS UNCLEAR

In recent years, several reports have raised concerns about the uncertain future of the TV dinner. “Has the Frozen Dinner Become Frozen in Place?” asked Advertising Age in 2012.

“Big trouble in the frozen food aisle” declared MSN Money in 2013. “Can Frozen-Food Companies Make TV Dinners Cool Again?” worried TIME. And just this past March, The Atlantic remarked: “America Is Falling Out of Love With TV Dinners.”

As noted in the Atlantic article (and echoed in several others), after nearly 60 years of growth, frozen meal sales have been on the decline since 2008. In the TIME article, Martha C. White writes (mirroring the other reports), “Our eating habits are shifting toward fresher, less processed foods.” But she adds, “What we’re eating may not necessarily be healthier – Panera’s Chipotle Chicken on Artisan French Bread sandwich, for example, sounds harmless, but it’s actually an 830-calorie fat-and-salt bomb. But many consumers feel like they’re eating healthier, and that perception shapes their choices when shopping at the grocery store, sandwich shop, or drive-through.”

Bob Goldin, the executive vice president of food-industry consulting firm Technomic, concurs. He explains, “Consumers tend to believe that frozen food probably doesn’t match the quality of fresh, restaurant-prepared meals,” as he told TIME.

Yet, another series of articles, such as this one from The New York Times, has recently emerged, focusing on a study conducted by three sociologists from North Carolina State University. The study argues that the stress of cooking, particularly for women, may not justify all the effort.

An article from Slate, titled “Let’s Stop Idealizing the Home-Cooked Family Dinner,” explains that researchers “discovered that ‘time constraints, compromises to save money, and the pressure to please others made it challenging for mothers to live up to the idealized vision of home-cooked meals promoted by foodies and public health advocates.’”

In response to the same study, Ester Bloom, in her piece titled “Are Family Dinners Anti-Feminist?” for The Billfold, suggests that families should “opt for a mix of ingredients, frozen foods, and prepared meals so everyone’s expectations stay realistic. Meals don’t need to be 100 percent home-cooked to be delicious and still more affordable and healthier than takeout.”