The relationship between Joséphine de Beauharnais and Napoleon Bonaparte is legendary. However, before their paths crossed, de Beauharnais endured considerable struggles. Even after marrying Napoleon—her second spouse—her life remained far from idyllic.

As Ridley Scott’s biopic Napoleon approaches its release, here are 11 fascinating facts about Joséphine de Beauharnais, the woman who spent 14 years living in the shadow of the emperor.

1. Joséphine de Beauharnais narrowly escaped being born British.

The Empress Joséphine. | Print Collector/GettyImages

The Empress Joséphine. | Print Collector/GettyImagesJoséphine’s family possessed sugar plantations in the small French colony of Martinique, located in the Caribbean Sea. The island had been a battleground between the French and British during the Seven Years War, with the British taking control in 1762. However, the 1763 Treaty of Paris resolved the conflict, returning Martinique to French rule just four months prior to Joséphine’s birth.

2. The name Joséphine de Beauharnais was never used during her lifetime—it didn’t exist.

Joséphine and Napoleon in their gardens. | Hulton Archive/GettyImages

Joséphine and Napoleon in their gardens. | Hulton Archive/GettyImagesJoséphine, the eldest daughter of Joseph Tascher de La Pagerie, was born on June 23, 1763, as Marie-Joseph-Rose. Her family affectionately called her Yeyette, and she was later known as Rose or Marie-Rose. After marrying Alexandre, Viscount of Beauharnais in 1779, she took on the title of Vicomtesse de Beauharnais. Her father, a gambler, had depleted the family’s fortune.

Napoleon was the one who chose to call her Joséphine, and after their meeting, she became Joséphine Bonaparte. The name Joséphine de Beauharnais is a historical amalgamation of the names she held throughout her life.

3. She was already a widow when she first encountered Napoleon.

Alexandre, Viscount of Beauharnais. | Heritage Images/GettyImages

Alexandre, Viscount of Beauharnais. | Heritage Images/GettyImagesJoséphine’s union with Alexandre was orchestrated by their families—she was just 16 when she traveled to France to meet her future husband. Alexandre displayed little affection for his young bride; his reasons for marrying her were largely driven by societal pressures and the desire to secure his inheritance. Dissatisfied with her education, he abandoned her for his mistress, Laure de Longpré, who bore him a child. Alexandre’s fate was sealed when he faced the guillotine during the Reign of Terror.

4. Joséphine and Alexandre, Viscount of Beauharnais, had two children together.

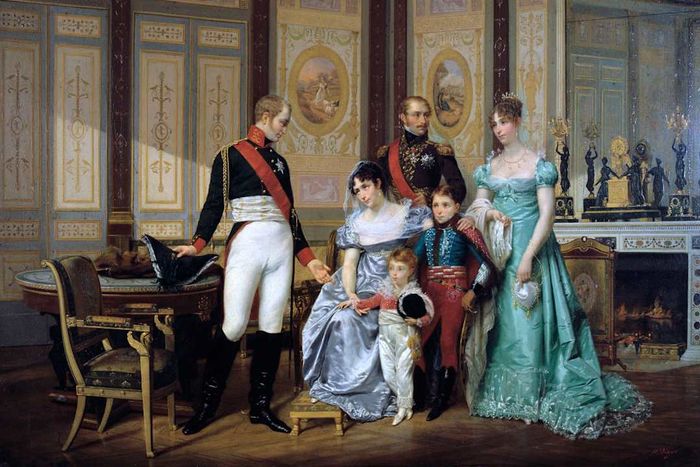

Joséphine presenting her children. | Print Collector/GettyImages

Joséphine presenting her children. | Print Collector/GettyImagesAlthough Joséphine’s marriage to Alexandre was far from harmonious, it did produce two children: a son and a daughter. Following their separation, their daughter, Hortense (born April 10, 1783), remained with Joséphine, while their son, Eugène (born September 3, 1781), eventually moved in with Alexandre. Both children maintained a close relationship with their mother throughout her life.

Napoleon held a deep affection for his stepchildren, treating them as his own, and Eugène frequently joined him on military campaigns. As Joséphine’s relationship with Napoleon began to falter, she orchestrated a marriage between Hortense and Napoleon’s brother Louis, partly to secure her own position. This marriage made Joséphine both a mother-in-law and sister-in-law to Louis, and when he ascended as King of Holland, Hortense became Queen.

5. Joséphine altered her birthdate on their marriage certificate to appear closer in age to Napoleon.

Napoleon Bonaparte and Joséphine de Beauharnais. | Apic/GettyImages

Napoleon Bonaparte and Joséphine de Beauharnais. | Apic/GettyImagesFollowing a whirlwind romance, Napoleon and Joséphine tied the knot on March 9, 1796, at the town hall in Paris’s 2nd Arrondissement. The ceremony was hastily arranged, and Napoleon arrived two hours late. Joséphine was 32, while Napoleon was 26; to minimize the age gap, both altered their birthdates on the marriage certificate. Joséphine shaved off four years, and Napoleon added 18 months.

6. Joséphine faced challenges with her in-laws from the very beginning.

Joséphine de Beauharnais at the end of her marriage to Napoleon. | Fototeca Storica Nazionale./GettyImages

Joséphine de Beauharnais at the end of her marriage to Napoleon. | Fototeca Storica Nazionale./GettyImagesThe Bonaparte family instantly disapproved of Joséphine. As an older woman with children, they deemed her an unsuitable match for Napoleon. Her extravagant lifestyle and free-spending habits clashed with their values of frugality and family devotion, and her social grace and sophistication intimidated them. Throughout her marriage to Napoleon, her in-laws plotted to remove her from the picture and celebrated when the couple eventually parted ways.

7. Joséphine and Napoleon were married not once, but twice.

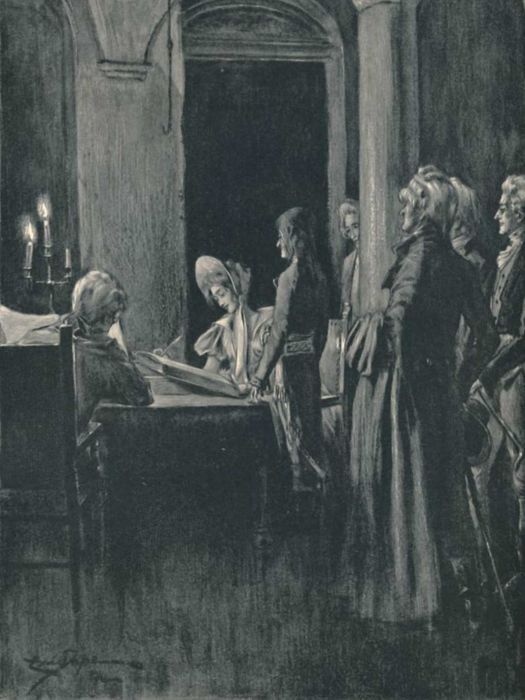

The Civil Marriage of Napoleon and Joséphine. | Print Collector/GettyImages

The Civil Marriage of Napoleon and Joséphine. | Print Collector/GettyImagesDissatisfied with the secular proclamation that declared him Emperor Napoleon I in May 1804, Napoleon sought a religious blessing. However, Pope Pius VII refused to condone an imperial couple living in what he considered sinful cohabitation due to their lack of a religious ceremony. He demanded they legitimize their union through religious vows, which they hastily performed on December 1, 1804—just one day before their coronation.

8. Napoleon personally crowned Joséphine as Empress.

Napoleon crowning Joséphine. | Print Collector/GettyImages

Napoleon crowning Joséphine. | Print Collector/GettyImagesThe coronation ceremony was held at Notre-Dame cathedral on December 2, 1804, with Pope Pius VII in attendance. Napoleon sought to balance the Pope’s blessing with a demonstration of his authority deriving from the people. Instead of allowing the Pope to crown them, Napoleon crowned himself and then placed Joséphine’s crown on his own head before transferring it to hers. Through this act, Joséphine was elevated to Empress of the French and Queen of Italy.

9. By the time she married Napoleon, Joséphine may have been unable to conceive.

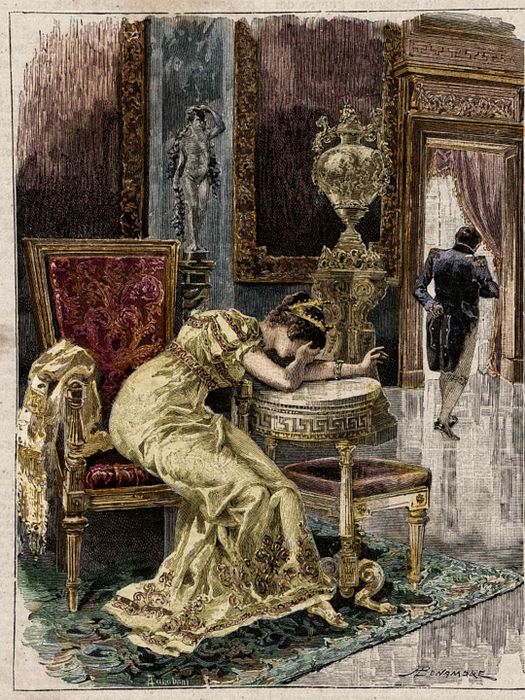

'The Divorce of the Empress Josephine' by Frederic Schopin. | Historical Picture Archive/GettyImages

'The Divorce of the Empress Josephine' by Frederic Schopin. | Historical Picture Archive/GettyImagesJoséphine made multiple attempts to address her infertility by visiting Plombières-les-Bains, a spa town in eastern France famous for its therapeutic waters. Despite her efforts, she never conceived a child with Napoleon. The precise reason for her infertility remains unclear, though some historians suggest that prolonged use of toxic cosmetics and contraceptive douches may have played a role. The absence of a legitimate heir—Napoleon fathered at least one child outside their marriage—ultimately led to the dissolution of their union in 1810.

10. Joséphine narrowly escaped death on several occasions.

Empress Joséphine. | Print Collector/GettyImages

Empress Joséphine. | Print Collector/GettyImagesIn 1788, Joséphine returned to her native island, Martinique, ostensibly to visit her elderly mother, though likely driven by a desire to escape the debts and scandals resulting from her numerous affairs at court. She narrowly avoided a cannonball while boarding her ship, as rising social unrest in Martinique forced her to hastily return to France.

Her challenges persisted upon her return to Paris during the Reign of Terror. In 1794, after her brother-in-law was jailed for his royalist leanings, both Alexandre and Joséphine were imprisoned shortly after. Alexandre was wrongfully convicted and executed by guillotine. Joséphine narrowly escaped the same fate when, just days after Alexandre’s death, the regime collapsed, the Reign of Terror ended, and she was freed along with many other prisoners.

Even a routine outing nearly proved fatal for Joséphine. In 1798, while staying at Plombières-les-Bains, she and her companions were called to a first-floor balcony by a maid who had spotted something intriguing outside. The balcony gave way under their combined weight, causing them to fall. Joséphine suffered severe back pain, a suspected fractured pelvis, and was temporarily unable to walk.

Her husband’s political career also posed dangers. In 1800, as First Consul of the French Republic, Napoleon faced numerous enemies. On Christmas Eve, a failed assassination attempt occurred while he was en route to the opera in a carriage. Although Napoleon emerged unharmed, Joséphine’s carriage was damaged, injuring her daughter and several bystanders.

Joséphine’s life came to an untimely end at the age of 51 at her residence, Chateau de Malmaison. After catching a cold, she ignored advice to rest and continued her social engagements. Her condition worsened rapidly, and she succumbed to a fever, passing away on May 19, 1814.

11. Joséphine rests eternally beside her daughter.

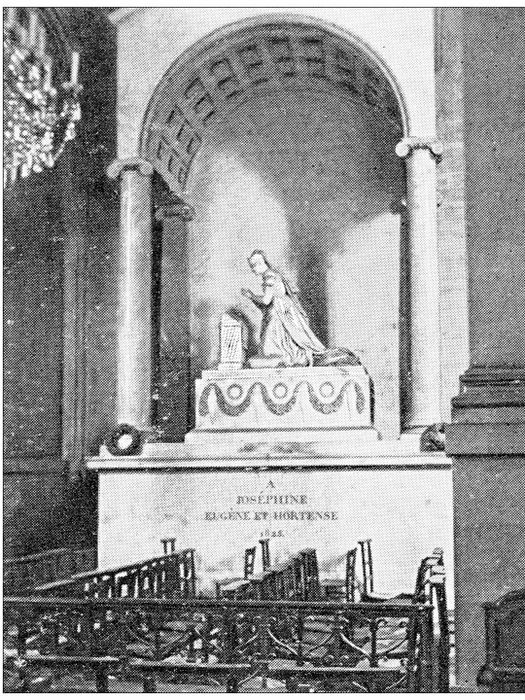

The tomb of Joséphine de Beauharnais. | ilbusca/DigitalVision Vectors/Getty Images

The tomb of Joséphine de Beauharnais. | ilbusca/DigitalVision Vectors/Getty ImagesJoséphine’s body was displayed for three days, allowing the public to mourn and honor her. On June 2, 1814, a solemn procession attended by thousands carried her to her final resting place in the Church of Saint-Pierre-Saint-Paul. Hortense and Eugène commissioned a sculptor to craft a statue of their mother, which was placed at the site in her honor. Hortense expressed her wish to be buried beside Joséphine, and upon her death in 1837 at age 54, she was laid to rest next to her mother.