Have you ever tuned into a TV show and thought, 'This drama is so impactful it might topple a corrupt regime,' or 'This sitcom could sway an election'? Perhaps you underestimate the power of television. While many criticize TV for societal issues, these series didn’t just entertain—they influenced the world to think differently.

Dallas

Dallas became a global phenomenon, especially in Nicolae Ceaușescu’s Romania. How did this soap opera bypass strict censorship? Thanks to its villainous protagonist, J.R. Ewing. Romanian officials likely saw J.R.’s corrupt oil tycoon character as a critique of capitalism, allowing the show to air in 1979. The portrayal of wealth and glamour, despite its moral flaws, resonated deeply with Romania’s struggling population, offering them a glimpse of a different world.

Eventually, the government concluded that Western television like Dallas was detrimental, leading to its removal from airwaves in 1981. Subsequently, Romania enforced a harsh austerity program, resulting in only a few hours of nightly TV broadcasts amidst other devastating outcomes. As reported by the LA Times, “On a typical evening, performers in formal attire recited patriotic poetry and sang praises to the 67-year-old leader, whose imposing portrait dominated the stage.” By 1989, Ceaușescu was overthrown, tried, and executed.

Years later, Larry Hagman, the actor behind J.R., visited Romania and was hailed as a hero. Reflecting on the experience, Hagman shared, “People in Bucharest approached me with tears, saying, ‘J.R. saved our nation.’”

General Electric Theater

In the early 1950s, Ronald Reagan, then a struggling film actor, seized the opportunity to host General Electric Theater, offered by Taft Schreiber of MCA. Earning $120,000 annually and eventually co-owning the show, Reagan also traveled across the U.S. as a “goodwill ambassador” for GE, delivering speeches and representing the company.

By the time General Electric Theater ended in 1962, Reagan had undergone a transformation. His years advocating for free enterprise with GE turned him into a prominent conservative voice. Although initially a Democrat, Reagan was persuaded by Schreiber to switch to the Republican Party. Four years later, he was elected California’s governor, paving the way for his future presidency.

This Is Early Bird

On April 6, 1965, NASA sent one of the first commercially funded satellites, Early Bird (later rechristened Intelsat 1), into orbit. Backed by the International Telecommunications Satellite Consortium (Intelsat), primarily led by the U.S. agency COMSAT, the satellite promised “nearly 10 times the capacity of undersea phone cables at a fraction of the cost,” as stated by NASA. This advantage persisted until the 1980s, when advanced cable technology emerged.

While groundbreaking, the venture was a significant gamble. Before Early Bird, space technology was predominantly government-controlled, and there was no certainty that the public would embrace satellites for television.

To captivate global audiences, Intelsat showcased Early Bird’s capabilities through This Is Early Bird. Just a month after launch, the special program connected 300 million viewers across Europe and North America. It featured live global broadcasts, including a heart surgery in Houston, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. addressing a crowd in Philadelphia, Pope Paul VI delivering a speech from the Vatican, a bullfight in Barcelona, and Russian sailors performing on the HMS Victory in England.

Cathy Come Home

Directed by Ken Loach, who later became a celebrated British filmmaker, the 1966 drama Cathy Come Home was a moving installment of the BBC-1 series The Wednesday Play. It depicted the heartbreaking tale of Cathy, a young mother and wife who falls prey to the flaws of Britain’s welfare system. After moving from her small town to the city and marrying, her husband’s accident leads to unemployment, plunging the family into poverty. Cathy endures homelessness, separation from her husband, and the forced removal of her children by social services.

The show’s harrowing narrative was amplified by its documentary-like realism, blurring the line between drama and reality. While one official dismissed it as “full of errors,” Labour Party politician Anthony Greenwood called it “essential viewing for five years.” The public agreed, prompting a swift re-airing. Though direct societal impacts are hard to measure, Cathy Come Home undeniably contributed to reforms in British welfare laws and sparked widespread debate.

Star Trek

While some fans claim Star Trek inspired inventions like cell phones and 3D printers, this is mostly overstated (and, in the case of cell phones, mostly fictional). Engineers from companies like Nokia and General Electric have acknowledged drawing inspiration from the show’s futuristic concepts, but most real-world innovations owe little to the series.

However, Star Trek influenced the future in a more profound way. Breaking stereotypes, the U.S.S. Enterprise featured a diverse crew of different races and genders. Lieutenant Uhura, portrayed by Nichelle Nichols, became a symbol of empowerment for Black women, showing they could hold leadership roles. When Nichols considered leaving the show, Dr. Martin Luther King, who told her, “Don’t you understand how significant your character is?” convinced her to stay.

Years later, figures like Whoopi Goldberg and Dr. Mae Jemison, the first Black American woman astronaut, credited Lieutenant Uhura as a key influence in their professional journeys. Nichols also collaborated with NASA on an astronaut-recruitment initiative, which attracted trailblazers like Dr. Sally Ride, the first American woman in space, and Dr. Guion “Guy” Bluford, the first Black American man in space.

See It Now

Edward Murrow, host of See It Now. | John Springer Collection/GettyImages

Edward Murrow, host of See It Now. | John Springer Collection/GettyImagesFor those familiar with 1950s history (or the film Good Night, and Good Luck), the influence of journalist Edward R. Murrow on American politics is undeniable. His platform for driving change was the news program See It Now, which debuted in 1951.

Renowned for his World War II radio broadcasts, Murrow initially had little interest in television. He aimed to transcend the conventional talking-head formats and newsreels dominating nightly news. When he launched See It Now, he did it his way. The premiere featured the first live coast-to-coast broadcast, showcasing a split-screen of New York and San Francisco. Murrow also pioneered coverage of a typical day for Korean War soldiers. The show’s most significant impact came from exposing Senator Joseph McCarthy’s anti-communist crusade, revealing its destructive effects on lives and careers. Following Murrow’s broadcast on March 9, 1954, the U.S. Senate censured McCarthy, marking the end of McCarthyism.

Murrow didn’t shy away from challenging powerful figures, whether rogue senators or Big Tobacco. Two episodes of See It Now explored the connection between smoking and cancer—a bold move, given TV’s reliance on tobacco advertising. Murrow, a heavy smoker often seen with a cigarette on screen, succumbed to lung cancer in 1965.

The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour and Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In

The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour broke ground by mocking the Establishment, embracing counterculture, and featuring controversial artists like Joan Baez and the previously blacklisted Pete Seeger, leading to clashes with CBS censors.

Following its success, Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In emerged, dubbed as NBC’s “hip” take on comedy, securing its place in counterculture lore. Ironically, both shows may have inadvertently helped Richard Nixon win the presidency.

As a joke, Pat Paulsen from Smothers Brothers ran for president in 1968. “I’m a great candidate because I’m consistently unclear on the issues,” declared Paulsen, “and I keep making promises I can’t keep.” Despite his comedic intent, Paulsen claimed to have received 250,000 votes, potentially influencing one of the closest elections in history. He later mentioned that Hubert Humphrey, Nixon’s opponent, blamed him for the loss, saying, “He told me I cost him the election … and he wasn’t smiling.” However, Paulsen’s claims are questionable, as he received only 11 write-in votes in Texas and little evidence supports a significant impact elsewhere.

A stronger case for influencing the election outcome can be made for Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In. One of its writers, Paul Keyes, was a longtime Nixon supporter. The story goes that Nixon was persuaded to say “sock it to me” on the show, while Humphrey’s advisors convinced him to avoid it. Dick Martin later recalled that Humphrey was asked to do the same but declined.

The impact of Nixon’s “sock it to me” moment has been widely discussed. Some believe it softened Nixon’s serious image, while others contend that campaign ads during the show were more influential. Regardless, the perception that it mattered shaped history. In 2013, producer George Schlatter remarked, “Now, candidates appear on every show imaginable, but back then, it was groundbreaking.”

The Inventors

In 1970, The Inventors became the American Idol for brilliant minds in the Southern Hemisphere. The judges, mostly science and business experts, were as intimidating as Simon Cowell, but Diana Fisher balanced the panel by representing the consumer perspective. While contestants weren’t always as talented as Kelly Clarkson, the show produced its own stars. Ralph Sarich, the biggest winner, invented the orbital engine, a low-emission, high-power system that seemed revolutionary. By 1972, Sarich had secured a multimillion-dollar deal with an Australian manufacturer. Although the orbital engine didn’t succeed, engines using its technology found some success. Sarich later sold his shares and invested in real estate, becoming one of Australia’s wealthiest individuals.

Hour of Decision

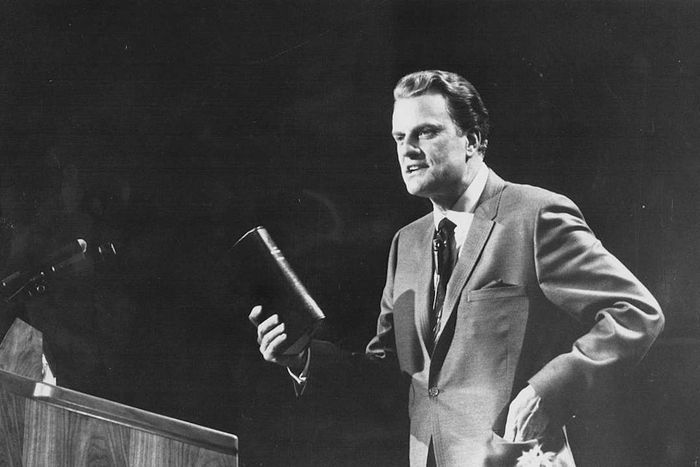

Billy Graham. | Keystone/GettyImages

Billy Graham. | Keystone/GettyImagesHour of Decision didn’t just bring televangelism to America; it introduced the nation to Reverend Billy Graham, the televangelist who would leave a lasting impact.

While other evangelists like Bishop James Pike, Fulton J. Sheen, and Oral Roberts had TV shows in the 1950s, none matched the charisma and influence of Reverend Graham. Adapted from his popular radio show, Hour of Decision included religious music, Graham’s sermons, and prerecorded interviews. Despite its short two-and-a-half-year run and limited success—Graham once remarked, “They are interesting films, but I can’t find anyone who ever saw one! Prime time on Sunday nights on network TV, and no one remembers”—he continued his TV ministry with live broadcasts from his Madison Square Garden crusades, engaging audiences nationwide.

Graham’s broadcasts were immensely popular, turning him into a national icon. Consistently ranked among the “most admired Americans” in Gallup Polls, the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association received around 50,000 letters weekly from viewers.

The Living Planet

Sir David Attenborough, one of Britain’s most respected environmentalists, owes much of his influence to television. Starting with Zoo Quest in the 1950s, Attenborough gained fame, but his breakthrough came with the 1979 series Life on Earth. This 13-part documentary explored the evolution of life, with the crew traveling over 1.5 million miles to more than 30 countries in three years.

The success of Life on Earth led to its Emmy-winning follow-up, The Living Planet, in 1984. This series highlighted how species adapt to their environments and how humans exploit them. “The natural world is constantly changing,” Attenborough stated. “But humans are causing such rapid changes that species can’t adapt. The future of life now depends on us.”

Attenborough wasn’t the first to raise these concerns, but he was the first to truly capture global attention. The Living Planet aired worldwide, earning Attenborough widespread admiration and inspiring the Green Movement.