For many children in the U.S., August signals the return to school, often met with little enthusiasm. However, comparing modern education to the realities of 19th-century American schools might make them appreciate how much easier they have it today.

1. In certain regions, education was conducted in a single-room setting.

A teacher and students gathered outside their one-room schoolhouse. | Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

A teacher and students gathered outside their one-room schoolhouse. | Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainDuring the 19th and early 20th centuries, one-room schoolhouses were common in rural regions. A solitary educator instructed students from grades one through eight simultaneously. The youngest learners, known as Abecedarians due to their focus on learning the ABCs, occupied the front rows, while the oldest students sat at the back. Heating was provided by a single wood-burning stove.

2. Transportation to school was nonexistent.

The tales of children walking five miles to school, uphill in both directions, hold some truth. Schoolhouses were typically located within four or five miles of students' homes, a distance deemed reasonable for walking.

3. In some cases, boys and girls were taught separately.

Boys were never seen in a sewing class like this one. | Heritage Images/GettyImages

Boys were never seen in a sewing class like this one. | Heritage Images/GettyImagesIn certain schools, boys and girls used different entrances and were kept separated during lessons.

4. The academic year was significantly shorter.

When the Department of Education started collecting data in the 1869–70 school year [PDF], students attended classes for approximately 132 days (compared to today’s 180-day standard), as they were often needed to assist with family farm work. Attendance rates were only 59 percent. School hours usually ran from 9 a.m. to 2 p.m. or 4 p.m., with a one-hour break for recess and lunch, referred to as “nooning."

5. School supplies were far from elaborate.

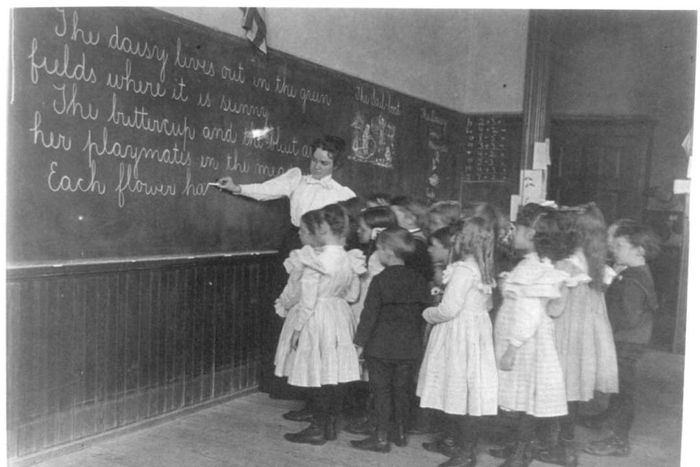

Chalk was the primary tool for instruction. | Heritage Images/GettyImages

Chalk was the primary tool for instruction. | Heritage Images/GettyImagesUnlike today’s Trapper Keepers and gel pens, students in the 19th and early 20th centuries relied on just a slate and a piece of chalk [PDF].

6. Pupils often assisted the teacher in lessons.

Under the monitorial or Lancasterian system, older and more advanced students received instruction directly from the teacher and then passed on their knowledge to younger or less experienced pupils.

7. Educational lessons in the 19th and early 20th centuries were vastly different.

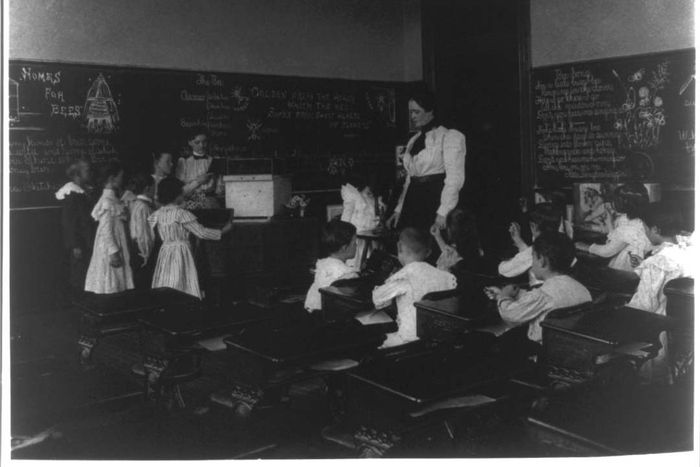

No cell phones were present. | Heritage Images/GettyImages

No cell phones were present. | Heritage Images/GettyImagesInstructors covered subjects such as reading, writing, math, history, grammar, rhetoric, and geography (examples of 19th-century textbooks can be found here). Students memorized their lessons and were called to the front of the class to recite what they had learned, allowing the teacher to correct errors like pronunciation immediately, while the rest of the class continued their work in the background.

8. Teachers occasionally resided with their students’ families.

As noted by Michael Day of the Country School Association of America, this arrangement was known as “boarding round,” where teachers would rotate between students’ homes, sometimes as frequently as weekly. A Wisconsin teacher in 1851 described the experience:

“It was quite uncomfortable, particularly during the winter and spring terms. One week, I would have a cozy room, and the next, my room would be so drafty that snow would blow in, even landing on and inside my bed. Some homes provided flannel sheets, while others offered only cotton. The worst part was trudging through snow and water, which left me frequently suffering from colds and a persistent cough.”

9. Classroom discipline was extremely rigid.

Students knew the consequences of misbehaving. | Heritage Images/GettyImages

Students knew the consequences of misbehaving. | Heritage Images/GettyImagesIn the 1800s and early 1900s, misbehavior could lead to detention, suspension, or expulsion—and in some cases, even physical punishment. A document [PDF] from the Franklin, Ohio Board of Education in 1883 outlined strict rules for students and teachers:

“Students may be held back during recess or kept for up to fifteen minutes after school if the teacher deems it necessary, either to complete lessons or to enforce discipline. … When corporal punishment is required, it must not be applied to the head or hands of the student.”

However, not all regions enforced such rules. In some areas, teachers used rulers or pointers to strike students’ knuckles or palms [PDF]. Other disciplinary measures included holding a heavy book for over an hour or writing repetitive sentences like “I will not…” on the blackboard 100 times.

10. Schools in the 1800s did not provide lunches.

Children carried their lunches to school in metal buckets. All students shared water from a single bucket, using the same tin cup filled by older boys. This practice started to shift in the early 1900s.

11. For numerous students, formal education concluded after eighth grade.

Education was primarily for the young. | Heritage Images/GettyImages

Education was primarily for the young. | Heritage Images/GettyImagesGraduation required passing a final exam. A sample eighth-grade test from Nebraska in 1895, available in this PDF, featured questions such as “Identify the parts of speech and explain those without modifications,” “A wagon box measures 2 feet deep, 10 feet long, and 3 feet wide. How many bushels of wheat can it hold?,” and “Define elementary sounds and explain their classification.”