During the 2010s, many people received chain emails titled 'Life in the 1500s,' filled with fascinating but entirely fabricated tales about phrases like throw the baby out with the bath water and chew the fat. While these stories are captivating, they’re far from accurate. Here’s the truth behind these commonly misunderstood sayings.

1. To Throw the Baby Out With the Bath Water

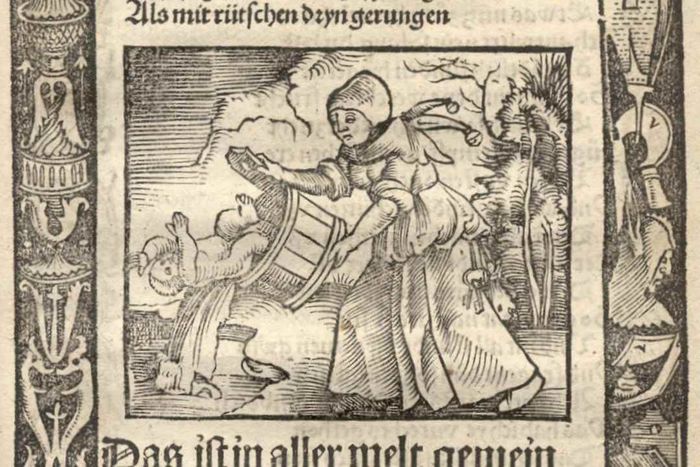

A woodcut from the 1512 satirical work 'Narrenbeschwörung.' | Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

A woodcut from the 1512 satirical work 'Narrenbeschwörung.' | Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainAccording to popular folklore, 16th-century bathing rituals involved a large tub of hot water. The head of the household would bathe first, enjoying the cleanest water, followed by the men, women, and finally the children, with babies last. By then, the water was so murky that a baby could supposedly be lost in it—leading to the phrase don’t throw the baby out with the bath water.

However, the reality is quite different. In the 1500s, filling a large tub with hot water was an enormous effort, as running water meant relying on rivers. Most people settled for sponge baths. The phrase originated from the German proverb “Das Kind mit dem Bade ausschütten [to empty out the child with the bath],” which first appeared in Thomas Murner’s 1512 satirical work Narrenbeschwörung (Appeal to Fools). A woodcut from the book shows a baby being bathed in a tub, but the water wasn’t deep enough to lose a child. The phrase likely became popular because it’s far more vivid than alternatives like “throw away the wheat with the chaff” or “throw the good away with the bad.”

2. Raining Cats and Dogs

In the 1500s, homes featured thatched roofs made of thick straw layered over wooden beams. Legend has it that small animals like cats, dogs, mice, and bugs sought warmth in these roofs. When it rained, the straw would become slippery, causing the animals to slide off—hence the expression it’s raining cats and dogs.

While mice and rats (not cats and dogs) did nest in thatched roofs, they would need to be on the roof's surface to slide off during rain. The phrase first appeared in writing during the 17th century, not the 16th, and etymologists have proposed various theories about its origin.

One theory suggests the phrase reflects the fierce rivalry between cats and dogs, symbolizing intense conflict or chaos.

Another idea, proposed by William and Mary Morris, links the phrase to medieval beliefs about witches as black cats riding storms and the Norse god Odin’s association with dogs and wolves. However, since the phrase emerged much later, these connections are unlikely. As linguist Anatoly Liberman of the University of Minnesota explains, “In Norse mythology, Odin is not a storm god, his ‘animals’ are a horse and two ravens, cats have no connection to Odin or witches, and rain isn’t tied to any deity.”

Gary Martin, who writes for the Phrase Finder website, dismisses the theory that raining cats and dogs derives from the French word catadoupe, meaning 'waterfall,' citing no evidence. He also labels the idea that rainwater carried dead animals and debris through 17th- and 18th-century English streets as 'purely speculative.'

Liberman, however, suggests a clue might lie in a variant of the phrase: 'raining cats and dogs, and pitchforks with their points downward.' This implies 'cats and dogs' may not refer to animals. He references a 1592 line: 'In steed of thunderboltes, shooteth nothing but dogboltes, or catboltes.' A 1918 text explains that dogboltes and catboltes were terms for iron bars securing doors or gates and bolts fastening timber. Liberman theorizes that people might have compared heavy rain or hail to these iron tools falling from the sky, inspired by the model of 'thunderbolt.'

However, not everyone agrees with this explanation either. Pascal Tréguer from Word Histories notes that the reference to dogboltes and catboltes isn’t related to weather but rather leans toward the conflict explanation. Still, these intricate backstories might be unnecessary. The phrase 'raining cats and dogs' could simply be a vivid metaphor for a heavy, relentless storm.

3. Bring Home the Bacon

Numerous theories exist about the origins of the phrase 'bring home the bacon.' | Owen Franken/Corbis Documentary/Getty Images

Numerous theories exist about the origins of the phrase 'bring home the bacon.' | Owen Franken/Corbis Documentary/Getty ImagesAccording to folklore, pork was a luxury in the 1500s, not accessible to everyone. Those who could acquire it felt a sense of pride. When guests visited, they would display their bacon as a status symbol, signifying that a man 'could bring home the bacon.'

Numerous tales surround the origins of the phrase bring home the bacon, none of which align with the story above. Some attribute it to winning a greased pig at a fair and taking it home as a prize. Others link it to an old English tradition where a 'flitch of bacon' (a side of pork) was awarded to married couples—or at least men—who could vow they hadn’t regretted their marriage for a year and a day. Chaucer’s 'Wife of Bath' mentions this custom, which still exists in a few English villages. However, the phrase didn’t appear in print until 1906, when a New York newspaper quoted a telegram from a boxer’s mother urging him to '[Y]ou bring home the bacon.' The expression quickly gained popularity among sportswriters covering boxing.

4. Dirt Poor

A commonly repeated origin for this phrase is that, in earlier times, floors were made of dirt, and only the wealthy could afford something better.

While dirt floors were common in certain periods, this has little to do with the phrase’s origin, which emerged much later and across the ocean. The term dirt poor appeared frequently in the 19th century, often in unusual contexts. For example, in 1860, a type of guano was described as 'nearly dirt poor as a fertilizer,' and in 1865, a mine was called 'dirt poor.' By 1885, a North Carolina newspaper used the phrase to describe how cotton farming was impoverishing farmers, leading to foreclosures and leaving merchants 'dirt poor.' WordOrigins.org speculates the phrase relates to the modern term house poor, indicating someone with land but little money. By the late 1880s, it evolved to describe anyone with minimal cash.

5. Threshold

The term 'threshold' has no connection to holding back thresh. | boblin/E+/Getty Images

The term 'threshold' has no connection to holding back thresh. | boblin/E+/Getty ImagesAs folklore goes, the word threshold supposedly originated from wealthy homeowners who used slate floors. These floors became slippery in winter when wet, so they spread thresh (straw) to improve traction. Over time, more thresh was added, and when the door opened, it would spill outside. A wooden piece was then placed at the entryway, creating a 'thresh hold.'

While rushes or reeds were indeed used to cover floors, this has no bearing on the word’s origin. Although rushes were sometimes called 'thresh' in Scots, threshold derives from therscold or threscold, linked to the German dialect term Drischaufel. The first part may relate to 'thresh' (meaning 'tread' in Germanic contexts), but the second part’s origin remains unclear. (Liberman suggests it originally referred to a threshing floor—where grain was separated—but later shifted in meaning for unknown reasons.)

6. Chew the Fat

As the story goes, this phrase originated from social gatherings where hosts would slice off a bit of bacon to share with guests. Everyone would sit together and 'chew the fat.'

The Oxford English Dictionary links chew the fat to chew the rag. Both phrases emerged in the late 19th century, not the 16th, and mean 'to discuss a topic, often complainingly; to revisit old grievances; to grumble, argue, or simply chat.' In Life in the ranks of the British Army in India and on Board a Troopship (1885), J. Brunlees Patterson mentions activities like 'whistling, singing, arguing, chewing the rag, or fat.' Essentially, chewing the fat refers to idle chatter and has no connection to actual fat.

7. Dead Ringer

While the fear of being buried alive was real, it didn’t inspire the phrase 'dead ringer.' | Karim Akrrimi/EyeEm/Getty Images

While the fear of being buried alive was real, it didn’t inspire the phrase 'dead ringer.' | Karim Akrrimi/EyeEm/Getty ImagesAccording to internet lore, England’s limited space led to a practice of exhuming coffins, moving bones to a 'bone-house,' and reusing graves. Upon reopening coffins, scratch marks were found inside one out of 25, suggesting people had been buried alive. To prevent this, undertakers tied a string to the corpse’s wrist, threaded it through the coffin and ground, and attached it to a bell. This supposedly led to phrases like 'saved by the bell' or 'dead ringer.'

While the fear of being buried alive was genuine, the story is largely fictional. In the 19th century, doctors investigated such claims but consistently failed to find evidence. A 1897 report noted that physicians unanimously agreed they had never encountered a verified case of live burial. Despite this, sensational headlines persisted, and inventors created signaling systems, some involving bells, to address the fear.

However, none of this explains the origin of dead ringer. The term ringer refers to a look-alike horse, athlete, or competitor fraudulently substituted in a contest. It stems from the slang verb to ring or ring the changes, meaning 'to fraudulently swap one thing for another.' (Ring the changes relates to 'change-ringing,' where teams play tunes on church bells.) Originally, the ringer was the person performing the swap; later, it referred to the substitute. Dead here means 'exact' or 'complete,' as in 'dead ahead' or dead easy. Thus, a dead ringer is an exact duplicate.

8. Saved by the Bell

Some link saved by the bell to coffin alarm systems, while others tie it to students hoping the school bell would save them from answering tough questions. In reality, the phrase originates from boxing, where it meant being saved from a knockout by the round-ending bell. It first appeared in writing in the late 19th century.

9. Graveyard Shift

The term 'graveyard shift' isn’t related to working in cemeteries. | gremlin/E+/Getty Images

The term 'graveyard shift' isn’t related to working in cemeteries. | gremlin/E+/Getty ImagesIf the earlier debunked legends were true (which they aren’t), someone would need to stay in a graveyard overnight to listen for bells, supposedly explaining the phrase the graveyard shift. However, graveyard shifts have no connection to actual graveyards—they simply evoke the eerie, quiet atmosphere of working late at night.

The phrase first emerged in the late 19th century. In 1888, a report on gambling houses referred to the 'graveyard shift' as the period after midnight. In August 1906, an article titled 'Ghosts in Deep Mines' described the 'graveyard shift' as typically between 11 p.m. and 3 a.m., noting its eerie superstitions. Sailors also had a 'graveyard watch,' usually from midnight to 4 a.m. Gershom Bradford’s A Glossary of Sea Terms (1927) linked it to frequent disasters during this time, while others attributed it to the ship’s silence.

10. Trench Mouth

Legend has it that in the 1500s, most people didn’t use pewter plates but instead relied on trenchers—wooden slabs hollowed out like bowls. These trenchers were often made from stale, hardened bread and were rarely washed, leading to infestations of worms and mold. Eating from these contaminated trenchers supposedly caused 'trench mouth.'

The truth is: Trencher, derived from Anglo-Norman, is related to the modern French word trancher, meaning to cut or slice. The Oxford English Dictionary notes its appearance in English during the 1300s, referring to a knife, a wooden serving board, a 'platter of wood, metal, or earthenware,' or 'a slice of bread used as a plate.'

While wooden boards can harbor pathogens, they aren’t the source of the term trench mouth. The phrase first appeared in Progressive Medicine in 1917, coinciding with World War I and trench warfare. Trench mouth refers to ulcerative gingivitis caused by bacteria, likely spread among soldiers sharing water bottles in the trenches, not by worms or mold.

11. Upper Crust

The modern interpretation of 'upper crust' likely has no connection to bread distribution. | Kseniya Ovchinnikova/Moment/Getty Images

The modern interpretation of 'upper crust' likely has no connection to bread distribution. | Kseniya Ovchinnikova/Moment/Getty ImagesAccording to legend, bread in the past was divided by social status. Workers received the burnt bottom, the family got the middle, and guests were given the top, or 'upper crust.'

A single historical source hints at this practice. John Russell’s Boke of Nurture, circa 1460, one of the earliest books on household management, advises (in modernized terms), 'Take a loaf … and prepare a trencher for your lord; arrange four trenchers in a square, with one on top. Use a light loaf, trim the edges, and serve the upper crust to your lord.' It’s unclear whether the upper crust was prized for its flavor or its durability as a plate substitute, but no other sources corroborate this custom. Over time, upper crust referred to the earth’s surface, bread, and pies, but its association with the elite didn’t emerge until the 19th century, making the bread-dividing theory unlikely.

In the 1800s, upper crust became slang for the head or a hat. In 1826, The Sporting Magazine noted, 'Tom completely tinkered his antagonist’s upper-crust.' The term likely evolved into a metaphor for the aristocracy due to its association with being 'the top.' As Thomas Chandler Haliburton wrote in 1838’s The Clockmaker; or the sayings and doings of Samuel Slick, of Slickville: “It was none o’ your skim-milk parties, but superfine uppercrust real jam.”

12. Wake

In the past, lead cups were commonly used for drinking ale or whiskey. Legend has it that the combination of lead and alcohol could knock someone unconscious for days, leading passersby to assume they were dead and prepare them for burial. The unconscious person would be laid out on the kitchen table while the family gathered, ate, drank, and waited to see if they would wake up—thus giving rise to the tradition of holding a 'wake.'

However, while pewter cups containing lead were used, lead poisoning is typically a slow, cumulative process. If someone passed out from excessive ale consumption, the lead in the cup wasn’t the cause.

The lead theory is false, but the practice of holding wakes in many cultures may have stemmed from the fear of premature burial. The term wake in this context doesn’t come from the idea of waking up but rather refers to a 'watch' or 'vigil.'

Additional Sources: Buried Alive: The Terrifying History of Our Most Primal Fear; “Food and Drink in Elizabethan England,” Daily Life through History; Oxford Dictionary of Music (6th ed.); ”English Ale and Beer: 16th Century,” Daily Life through History; Of Nurture (in Early English Meals and Manners, Project Gutenberg; Domestic architecture: containing a history of the science; “Housing in Elizabethan England,” Daily Life through History Morris Dictionary of Word and Phrase Origins, 1971; New Oxford American Dictionary, 2nd ed.

This article merges two earlier pieces from 2014 and 2016, now updated with fresh research for 2022.