In his 1943 masterpiece Rosie the Riveter, artist Norman Rockwell (1894–1978) encapsulated the spirit of 1940s America: Rosie, with her sleeves rolled up, symbolizes the hardworking home front, mirroring the efforts of soldiers on the battlefield.

Mary Doyle Keefe, a 19-year-old telephone operator and Rockwell's neighbor, served as the real-life inspiration for Rosie. Rockwell frequently used real people—friends, neighbors, and models—as references, a practice that helped cement his legacy as one of the 20th century's most celebrated artists. Discover more about the individuals who shared their faces with Rockwell and the world.

1. Ruby Bridges and Lynda Gunn // The Problem We All Live With

A 2017 photograph of Ruby Bridges. | Dimitrios Kambouris/GettyImages

A 2017 photograph of Ruby Bridges. | Dimitrios Kambouris/GettyImagesWhile Rockwell’s art often stirs nostalgia for a bygone era, it also highlights moments of societal upheaval. His 1964 painting The Problem We All Live With portrays a young Black girl being escorted by four U.S. marshals to a recently desegregated school. The wall behind her, marked with graffiti and splattered tomatoes, starkly reflects the racial tensions of the time. (The painting can be viewed here.)

The girl in the painting is Ruby Bridges, who, in 1960, became the first Black student to attend William Frantz Elementary in New Orleans after a federal desegregation mandate. Unlike most of Rockwell’s subjects, he never met Bridges in person; instead, he relied on photographs of her for reference. Additionally, he enlisted Lynda Gunn, an 8-year-old granddaughter of a friend, to model the scene for him.

Bridges only discovered the painting in the 1970s. Decades later, the artwork was displayed at the White House during a 2011 exhibition, where Bridges was a special guest. Gunn, whose contribution is often overlooked, was not invited. In a 2011 interview with The New Yorker, Gunn expressed pride in her role but noted she would have appreciated a royalty rather than the $10 fee Rockwell paid her.

2. Bess Wheaton // Freedom From Want

'Freedom From Want.' | Library of Congress/GettyImages

'Freedom From Want.' | Library of Congress/GettyImagesAs part of Rockwell’s Four Freedoms collection, Freedom From Want (1943) illustrates a family gathering for a Thanksgiving meal. The painting symbolizes not just physical nourishment but also emotional fulfillment. (Rockwell, however, feared some might interpret the lavish spread as excessive.) Among the intricate details—such as a guest making eye contact with the viewer—the central figure is the woman serving the turkey.

The woman in the painting is Bess Wheaton, Rockwell’s actual family cook. She prepared the perfectly roasted turkey and other dishes for Rockwell’s reference, and the family enjoyed the meal to ensure nothing went to waste.

Wheaton wasn’t the sole model in the artwork. Rockwell’s second wife, Mary, appears on the right, seated beside Rockwell’s mother, Nancy, while their neighbor Jim Martin is the guest engaging directly with the viewer.

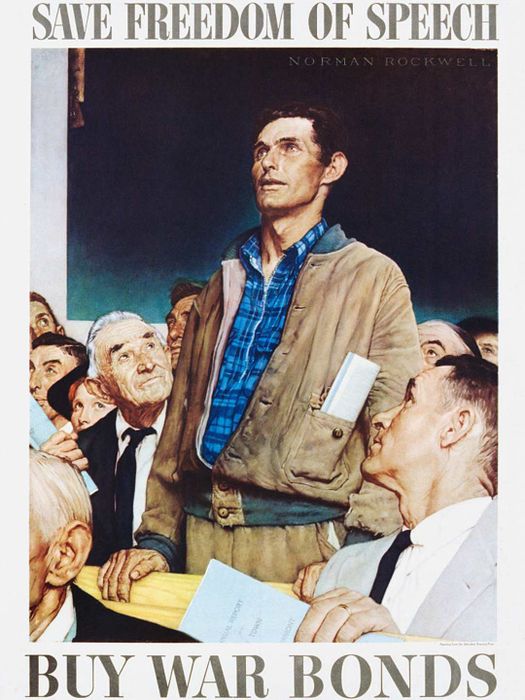

3. Carl Hess // Freedom of Speech

'Freedom of Speech.' | swim ink 2 llc/GettyImages

'Freedom of Speech.' | swim ink 2 llc/GettyImagesAnother piece from Rockwell’s Four Freedoms series—alongside Freedom of Worship and Freedom From Fear—Freedom of Speech (1943) portrays a working-class man boldly expressing his views at a town meeting.

The figure in the painting was Carl Hess, a local from Arlington, Vermont, who worked as an independent mechanic. Rockwell used Hess’s appearance but drew inspiration from another Arlington resident, James Edgerton, who had voiced his opposition to a tax hike at a town meeting. Rockwell felt Hess embodied the same sincere demeanor as Abraham Lincoln. Hess also appears in another Rockwell piece, playing checkers on a cover of The Saturday Evening Post.

4. Jim Stafford // Window Washer

Norman Rockwell. | John Springer Collection/GettyImages

Norman Rockwell. | John Springer Collection/GettyImagesIn 1960, Rockwell created a painting of a window washer (viewable here) for The Saturday Evening Post. The man, appearing unbothered by heights, seems more captivated by the stenographer inside the office than by his own task.

The man on the scaffolding is Jim Stafford. Unlike most of Rockwell’s models, who lived near him in Arlington, Vermont, or later in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, Stafford was an admirer who sent a letter requesting to visit Rockwell’s studio. Rockwell agreed, but Stafford quickly realized Rockwell had an ulterior motive. He used Stafford as the window washer, inviting him to stay at his home for a few days to take reference photos. Rockwell even offered to introduce Stafford to the stenographer model, but Stafford refused. Stafford later became a celebrated artist himself.

5. Mary Whalen // The Young Lady With the Shiner

Rockwell’s 1953 painting of a defiant young girl was inspired by a local connection: 11-year-old Mary Whalen, whom Rockwell met at a basketball game and deemed ideal for the role after painting her for a Plymouth ad. (She also happened to be the daughter of Rockwell’s attorney.) Whalen later remembered being paid $5 and a Coca-Cola for her modeling work.

Of course, Rockwell didn’t need anyone to actually hit the girl for realism. He initially tried using charcoal to create the effect, but when that failed, he painted it directly. The principal’s door, however, was real—Rockwell had it taken from an elementary school and brought to his studio.

6. Howard Lincoln // The Scoutmaster

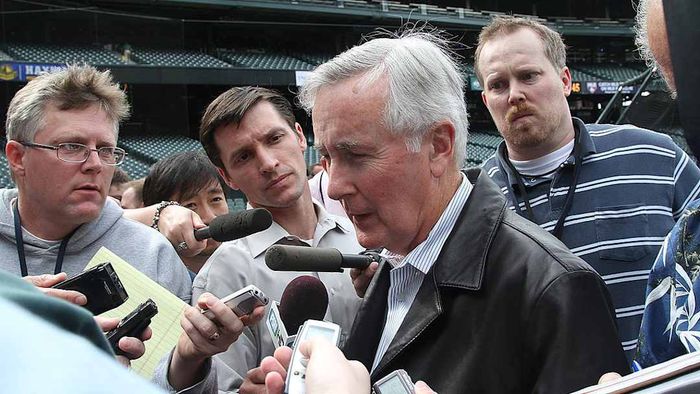

Howard Lincoln (center) modeling for Rockwell. | Otto Greule Jr/GettyImages

Howard Lincoln (center) modeling for Rockwell. | Otto Greule Jr/GettyImagesRockwell maintained a lasting relationship with the Boy Scouts of America, creating numerous artworks featuring the organization. One of the most notable is The Scoutmaster, a 1956 painting depicting young Scouts camping under the guidance of their leader.

Among the boys resting under the night sky is 12-year-old Howard Lincoln, who was attending a Boy Scout event in Irvine, California, when Rockwell approached him and other boys to ask for their participation. Despite the 90-degree heat, Rockwell had the boys set up camp and light a fire for reference photos, which he used for the artwork featured in a calendar.

While this was a memorable experience, it wasn’t Lincoln’s only notable achievement. He later became a lawyer and eventually rose to the position of chairman at Nintendo of America. The gaming company played a role in acquiring the Seattle Mariners in 1992, and in 1999, Lincoln became the team’s chairman and CEO.

7. Duane Parks // Homecoming Marine

While many World War II illustrations focus on the intensity of combat, Rockwell’s Homecoming Marine offers a quieter yet equally powerful scene. A soldier has returned from the battlefield and attempts to share his experiences with a captivated group in a mechanic’s garage. The somber atmosphere reflects the lingering impact of war.

The Marine in the painting is Duane Parks, a Vermont resident and war veteran whom Rockwell encountered at a dance. Parks had served as a gunner during the war. “I was at a dance in East Arlington,” Parks later recalled. “[Rockwell] approached me and asked if I’d like to be painted. I told him off.” Parks didn’t recognize Rockwell, but his family did. After their persuasion, he agreed to pose for photos, earning $10 for his time.

Rockwell cast his own sons as the two boys in the painting. On the Marine’s left is his son, Peter, and on the right is his other son, Jerry.

8. Bob Hamilton // We, Too, Have a Job to Do

For this 1944 portrait of a Boy Scout, Rockwell chose a fitting subject: an actual troop member. Scout Bob Hamilton posed for this propaganda artwork, which aimed to inspire Scouts and others to gather cans and rubber for the war effort. Hamilton later remembered Rockwell disliking his neckerchief slide and requesting a change.

9. Joan Lahart and Francis Mahoney // The Marriage License

Rockwell’s 1955 depiction of young love—and a weary clerk—was inspired by Joan Lahart and Francis Mahoney, an engaged couple from Lee, Massachusetts. Rockwell specifically chose a canary yellow dress for Lahart to create a striking contrast with the warm wooden tones of the clerk’s office.

The clerk in the painting also had a real-life counterpart. Rockwell asked Jason Braman to model, knowing Braman’s recent loss of his wife and hoping the work might provide some distraction.

10. Fred Hildebrandt // Sport

Rockwell had a passion for fishing, and it’s probable he had experienced a situation similar to the one depicted in Sport, a 1939 illustration where a man’s fishing trip is spoiled by rain. The outdoorsman in the painting is Fred Hildebrandt, a close friend of Rockwell’s who once joined him on a nine-day fishing adventure.

The bond between Rockwell and Hildebrandt eventually faded, though not because of the artwork. Hildebrandt, also an artist, may have felt overshadowed by Rockwell’s success, as noted by Rockwell biographer Deborah Solomon.

Sport also has the dubious honor of being one of Rockwell’s stolen pieces. After selling for approximately $1 million in 2013, the buyer stored it in a New York unit, where it vanished. A private investigator received an anonymous tip and recovered it months later in Ohio.

11. Cathy Burow // Prom Dress

Norman Rockwell. | Hulton Archive/GettyImages

Norman Rockwell. | Hulton Archive/GettyImagesBurow stands out in Rockwell’s work as one of the few models he didn’t source locally. In 1948, while in Los Angeles, Rockwell approached 14-year-old Cathy Smith (later Burow) to pose for a painting of a teenager getting ready for prom. With her junior high teacher’s approval and presence during Rockwell’s visit, Smith agreed. The outcome was Prom Dress, viewable here. Decades later, Burow’s only regret was that Rockwell didn’t let her keep the prom dress he had borrowed from a supplier. Instead, he gave her $10 and a hamburger.

12. Norman Rockwell // Triple Self-Portrait

Like many artists, Rockwell occasionally turned to his own reflection for inspiration. In Triple Self-Portrait (1960), Rockwell humorously depicted himself as more polished than he felt in reality. This was achieved by showing his painted self with fogged glasses, unable to see clearly and thus rendering an idealized version. It was a playful nod to his own modesty, despite his role as a chronicler of American life.