On September 8, 2022, King Charles III assumed the British throne—yet he wasn’t the initial claimant to the name Charles III.

Born over three centuries ago, Charles Edward Louis John Casimir Sylvester Severino Maria Stuart was the firstborn son of a monarch’s eldest son. By the laws of hereditary succession, he was the rightful heir to the crown. However, he never secured his destined throne. Discover 12 fascinating facts about the man history remembers as Bonnie Prince Charlie.

1. The grandfather of Bonnie Prince Charlie was King James II of England and James VII of Scotland, who was overthrown from power.

James II and VII. | Hulton Archive/GettyImages

James II and VII. | Hulton Archive/GettyImagesKing James II of England and VII of Scotland, the son of Charles I, reigned from 1685 to 1688. His unpopularity stemmed largely from his religious convictions. Despite being born into the Protestant Stuart dynasty, he converted to Roman Catholicism in 1669. To grasp why this alarmed his subjects, we must revisit the era of Elizabeth I.

In 1559, Elizabeth I inherited a nation rife with religious strife and managed to establish a lasting peace between Protestants and Catholics. The 1559 Act of Supremacy declared the queen, not the Pope, as the Supreme Governor of the Church of England, while the Act of Uniformity allowed both Catholic and Protestant communion practices. All monarchs after her were Protestant—until James II’s ascension reignited fears of religious chaos.

Initially, James II’s rule was accepted, partly due to the Protestant faith of his daughters, Mary and Anne. Mary, the heir, was wed to the Protestant William of Orange, a grandson of Charles I, ensuring a Protestant succession. However, in 1688, James’s second wife, Mary of Modena, bore a son, James Frances Edward Stuart, who was baptized Catholic. This shattered hopes of a Protestant line, prompting English nobles to invite William of Orange to claim the throne. In 1688, William and Mary overthrew James II in the Glorious Revolution, forcing him to flee to France under the protection of his cousin, King Louis XIV.

2. The title “The Young Pretender” was passed down to Bonnie Prince Charlie from his father.

“The Young Pretender.” | Print Collector/GettyImages

“The Young Pretender.” | Print Collector/GettyImagesFollowing James II’s death in 1701, the young James Frances Edward Stuart remained in exile in France under Louis XIV’s protection. The French King proclaimed him James III of England and James VIII of Scotland, titles endorsed by Spain and the Pope. In 1708, spurred by the Act of Union and supported by Louis, 19-year-old James attempted to invade Scotland but was defeated by harsh weather and the British Navy.

Over time, the British monarchy transitioned smoothly. After William III and Mary II died without heirs, the Crown went to Anne, Mary’s sister and the final Stuart monarch, in 1702. The 1707 Succession to the Crown Act mandated that the throne be inherited by the next Protestant in line. With Anne having no surviving children, the throne passed to a distant relative, George, Elector of Hanover, who became George I upon her death in 1714.

Despite setbacks, the supporters of the would-be James III in Britain, called Jacobites (from Jacobus, the Latin for James, a term first used for James II’s followers), persistently schemed to restore him. The Crown’s transfer to George I instead of James sparked the first Jacobite uprising in 1715, which ended in James’s defeat and his return to France. A second uprising in 1719 also failed.

By this period, James’s persistent claim to the Stuart throne was seen as an embarrassment in certain circles. He earned the nickname “The Old Pretender” for his ongoing pursuit of the Crown, a claim further tarnished by rumors surrounding his birth. His mother, Mary of Modena, had lost 10 children to miscarriages, stillbirths, and early deaths. When James was born four years after her last unsuccessful pregnancy, it fueled a conspiracy theory that he was an impostor smuggled into her chamber in a warming pan. To many, James was a “pretender” from birth, and his son inherited this derisive title, becoming known as “The Young Pretender.”

3. Bonnie Prince Charlie experienced a tumultuous upbringing in Italy.

Prince Charles Edward Stuart, circa the 1730s. | Print Collector/GettyImages

Prince Charles Edward Stuart, circa the 1730s. | Print Collector/GettyImagesFollowing the unsuccessful uprisings, James Frances Edward Stuart spent most of his later years near Rome. He wed Polish Princess Maria Clementina Sobieska, and they had two children. Charles Edward Stuart, later known as Bonnie Prince Charlie or “The Young Pretender,” was born in 1720 at the Palazzo del Re (or Palazzo Muti) in Rome, where the exiled Jacobites maintained their court. Just over four years later, Henry Benedict Stuart, who would become the Cardinal Duke of York, was born.

As an infant, Charles was looked after by a nurse, governess, and chambermaid, alongside his mother. When Henry was born, their father separated Charles from his mother and placed him under the care of male tutors, including a governor Maria despised. In response, Maria joined a convent, returning two years later. However, the relationship between Charles’s parents remained strained, marked by unhappiness until her early death when Charles was just 14.

4. Bonnie Prince Charlie championed his—and his father’s—claim to the throne.

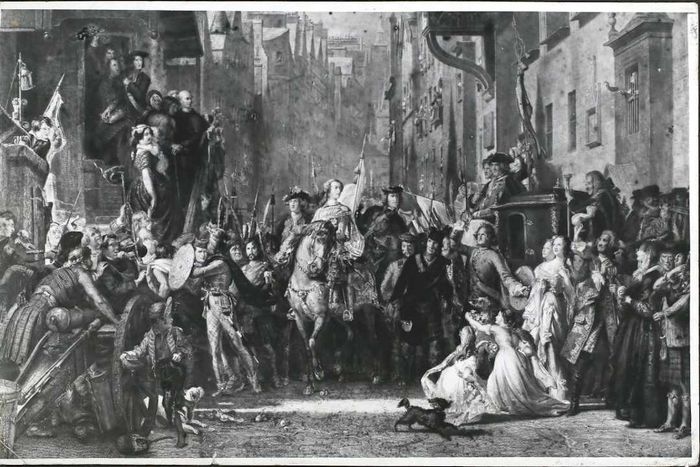

Bonnie Prince Charlie leading his troops into Edinburgh. | Hulton Archive/GettyImages

Bonnie Prince Charlie leading his troops into Edinburgh. | Hulton Archive/GettyImagesDespite any resentment Charles might have harbored toward James due to his parents’ fractured marriage, he embraced his role when his father appointed him Prince Regent in 1743, vowing to reclaim the throne in his name.

His initial invasion attempt came in 1744, with a heavily armed French fleet that was thwarted by severe weather before reaching shore. Undeterred and now lacking French backing, Charles seized the opportunity while the British Army was occupied abroad and launched a second attempt, boarding a French frigate. He arrived on July 23, 1745, with a small contingent on the Island of Eriskay in the Outer Hebrides. His goal was to amass a Highland army and gain enough support as he advanced south, hoping to rally English Jacobites and French military aid for the cause.

The third and final Jacobite uprising commenced on August 19, 1745, when Charles and his Highland forces raised their banner at Glenfinnan. By September 17, they had entered Edinburgh, establishing their court at Holyrood Palace and declaring James as King.

5. Bonnie Prince Charlie’s support extended well beyond the Scottish Highlands, though not all Highlanders backed his cause.

Supporters raising a toast to the prince. | Hulton Archive/GettyImages

Supporters raising a toast to the prince. | Hulton Archive/GettyImagesThe Jacobite Army is frequently thought to have been primarily composed of Highlanders, partly due to its nickname, the Highland Army. While the third uprising began in the Highlands, many locals joined because their clan chiefs compelled them, reflecting the social hierarchy of the Highlands at the time.

Numerous other Scots from the lowlands and eastern regions enlisted, likely influenced by pro-Jacobite landowners. As the army advanced to Edinburgh, more lowland Scots and even some English, such as the Manchester regiment, joined after crossing the border.

Jacobite loyalty extended to the Welsh, Irish, and French. Irish and French troops fought alongside the Jacobite Army at Culloden. Jacobitism had a strong presence in Ireland, fueled by English oppression; many Irish hoped a Stuart restoration would end their suffering. The French, already at war with Britain, supported the Jacobites to weaken their enemy and further their own interests.

However, not all Scots supported the Jacobite cause. Glasgow largely favored the Hanoverians, and Edinburgh maintained a government-controlled castle throughout the 1745 uprising. Some Highland chiefs also hesitated, fearing that without substantial French aid, victory was unlikely.

6. Bonnie Prince Charlie’s support was not limited to Catholics, nor were all his followers Catholic.

Bonnie Prince Charlie, circa 1750. | Print Collector/GettyImages

Bonnie Prince Charlie, circa 1750. | Print Collector/GettyImagesIt’s no surprise that the Jacobites garnered support from the Catholic community. Beyond sharing the Stuart family’s faith, British Catholics had endured numerous grievances since the reign of William III and Mary II, when they faced a series of oppressive government measures.

However, Jacobitism wasn’t exclusive to Catholics. Historical records indicate that many Highlanders were Protestant. Additionally, numerous Jacobites upheld the belief in the divine right of kings, the idea that monarchs derived their authority directly from God. The Stuarts had ruled Scotland since 1371 and united with England when James VI of Scotland became James I of England in 1603. Many Scots, both Catholic and Protestant, viewed the Stuart male line as the legitimate rulers. Some Jacobites, irrespective of religion, sought to reclaim Scotland’s independence lost under the 1707 Act of Union.

Despite the prospect of greater religious freedom under a Catholic ruler, prominent British Catholics like the Duke and Duchess of Norfolk remained loyal supporters of the Hanoverian king, likely due to Norfolk’s earlier pardon as a Jacobite sympathizer. Others appeared satisfied to practice their faith privately without opposing the Protestant monarchy.

7. Bonnie Prince Charlie came remarkably close to achieving his goal.

The Battle of Culloden, April 1746. | Print Collector/GettyImages

The Battle of Culloden, April 1746. | Print Collector/GettyImagesCharles’s strategy of invading while the British Army was occupied in the War of the Austrian Succession in Europe initially seemed successful. After capturing Edinburgh, he triumphed over the British at the Battle of Prestonpans on September 21, 1745. The Jacobites then advanced south, crossing into England. They seized Carlisle following a brief siege and moved through areas that had backed the 1715 uprising. However, fewer English supporters joined than anticipated, and the promised French invasion never occurred.

By December 4, the Jacobite Army had reached Derby, 480 miles from Charles’s initial landing at Eriskay and just 120 miles from London. By then, the Duke of Cumberland had been called back from leading the British Army in Europe and was advancing from London. To Charles’s frustration, his war council outvoted him, expressing concern over their isolation from Scotland and the lack of expected support; they urged a retreat to await French reinforcements. Despite his significant progress and proximity to victory, Charles reluctantly retreated to Scotland, where his forces regrouped and grew. They achieved success at the Battle of Falkirk Muir and captured Inverness.

As spring approached, the Jacobite Army faced shortages of money and supplies, while Cumberland’s troops had been trained in Jacobite combat tactics. The Royal Navy had seized a French ship carrying funds for the Jacobites, forcing Charles to act. On April 16, 1746, the two armies clashed at the infamous Battle of Culloden—the final pitched battle (a prearranged confrontation) on British soil. The Jacobites were heavily outnumbered by the Hanoverians, and within an hour, Bonnie Prince Charlie’s dream of reclaiming the throne was shattered. He fled, becoming a fugitive with a £30,000 bounty on his head.

8. Bonnie Prince Charlie disguised himself as a woman to escape the British army.

Bonnie Prince Charlie and Flora Macdonald. | Print Collector/GettyImages

Bonnie Prince Charlie and Flora Macdonald. | Print Collector/GettyImagesFollowing his defeat at Culloden, Charles was relentlessly hunted by Hanoverian forces across the Highlands and islands, narrowly evading capture multiple times. Courageous Scots risked their lives to provide him with food and shelter, aiding his escape. On April 27, he reached the Western Isles, constantly moving from one location to another until June 28, when he fled South Uist with the assistance of the local heroine, Flora MacDonald.

MacDonald proposed that Charles disguise himself as her Irish maid, Betty Burke. Under the cover of darkness, they sailed with five boatmen to the Isle of Skye, navigating the perilous waters of the Minch. Charles and his companions traveled across Skye, eventually parting ways with MacDonald and reaching the mainland. From there, they journeyed to Loch nan Uamh, where they boarded a French frigate on September 20, 1746.

9. Bonnie Prince Charlie’s adventures are celebrated in the “Skye Boat Song.”

Many view Charles’s life as a tale of a tragic hero, particularly during his months on the run after Culloden. His story is immortalized in the “Skye Boat Song,” with lyrics penned over a century later by Englishman Sir Harold Boulton. The song follows the structure of a traditional Gaelic rowing tune, set to the melody of an older song titled “The Cuckoo in the Grove” (the melody will be recognizable to Outlander fans). The opening verse captures the Jacobites’ poignant longing:

“Speed, bonnie boat, like a bird on the wing Onward, the sailors cry! Carry the lad that’s born to be King Over the sea to Skye.”

10. Bonnie Prince Charlie truly lived up to his name.

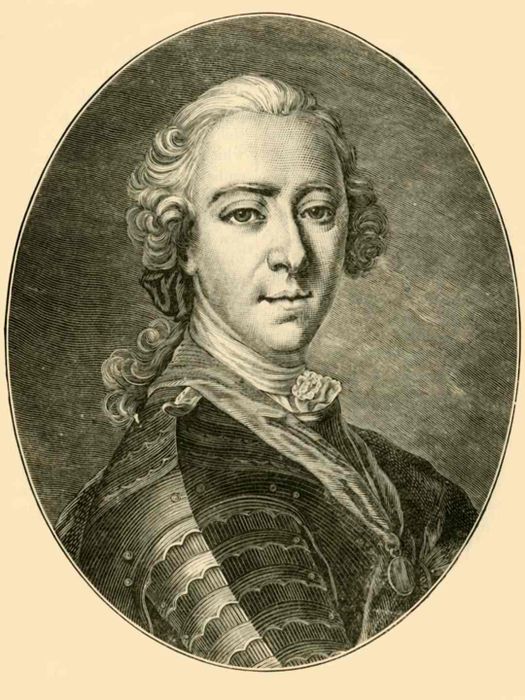

A portrait of Prince Charles Edward Stuart. | Culture Club/GettyImages

A portrait of Prince Charles Edward Stuart. | Culture Club/GettyImagesHistorically, royal portrait artists often idealized their subjects, aiming to convey symbolic meaning rather than strict realism. As Murray Pittock, a historian and professor at the University of Glasgow, explains, “Charles was depicted as youthful, fair, and feminine to symbolize renewal, fertility, and hope for Scotland.” This explains why he is frequently portrayed as a striking young figure. But how accurate were these depictions?

He earned the nickname “Bonnie” (meaning beautiful) during his stay in Edinburgh in the third Jacobite uprising, where he attracted numerous admirers among local women. Accounts from his youth describe him as both physically appealing and charismatic. Eyewitness reports from the 1745 uprising further confirm his charm and good looks.

A digital facial reconstruction created from his death mask by forensic artist Hew Morrison depicts Bonnie Prince Charlie in his later years. His features remain symmetrical and well-proportioned, aligning with traditional standards of attractiveness, making it easy to envision his youthful handsomeness.

11. Bonnie Prince Charlie passed away isolated and disheartened in Italy.

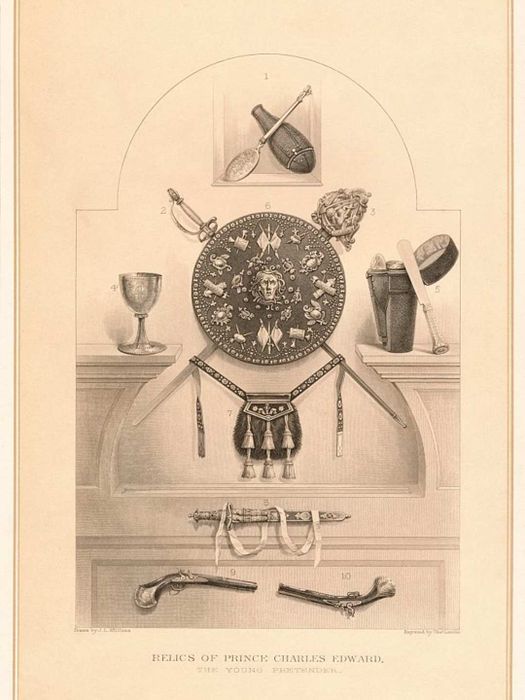

Relics of Bonnie Prince Charlie. | Print Collector/GettyImages

Relics of Bonnie Prince Charlie. | Print Collector/GettyImagesDescriptions of Charles’s later years paint a far less flattering picture. After fleeing Scotland in 1746, he returned to France, hoping to rally an army and resume his campaign, but support never materialized. In 1748, the Treaty of Aix-La-Chapelle ended the War of the Austrian Succession, and Charles was expelled from France as part of the agreement. He moved to Papal territories, and after his father’s death in 1766, the Pope allowed him to reside in the Palazzo Muti. However, when James died, Pope Clement XIII refused to grant Charles the title of Charles III, delivering yet another crushing disappointment.

Charles had been a heavy drinker since his youth, and his reliance on alcohol deepened as his disillusionment grew. In 1753, he fathered a daughter, Charlotte, with his mistress Clementina Walkinshaw; both mother and child eventually left him due to his alcoholism and abusive tendencies. In 1772, concerned about his lack of legitimate heirs, his supporters arranged his marriage to Princess Louise of Stolberg-Gedern. The union produced no children, and Charles grew increasingly isolated and bitter, perpetuating domestic abuse and succumbing to his drinking habits, which led to the collapse of his marriage.

After years of declining health, Charles suffered a stroke and died on January 31, 1788, at the age of 67, in the same Palazzo where he was born.

12. Bonnie Prince Charlie’s defeat paved the way for the Highland Clearances.

The Highland Soldier Monument, Glenfinnan, Scotland. | Tim Graham/GettyImages

The Highland Soldier Monument, Glenfinnan, Scotland. | Tim Graham/GettyImagesThe third uprising marked the breaking point for the British government. Resolved to eliminate any future rebellion, they ruthlessly dismantled the Highlanders’ way of life, destroying homes and executing or exiling Jacobite supporters—even children, who were sent to colonies as indentured servants, despite many Highlanders having no involvement in the uprising.

Traditional Highland attire, Gaelic language, weaponry, and bagpipes were outlawed. Clan chiefs lost their authority, ending their command over their people. The government enabled land acquisition, leading landlords to repurpose it for lucrative sheep and cattle farming. This resulted in the forced eviction of local families to coastal regions, where they struggled to farm infertile land. Others were relocated as crofters, working land they didn’t own. Many Highlanders eventually emigrated, their traditional lifestyle eradicated forever.