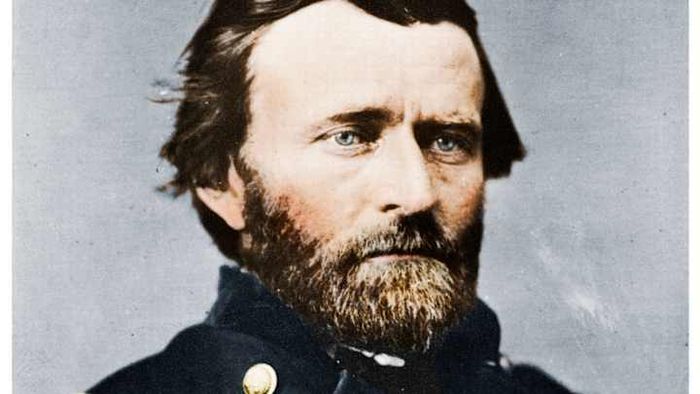

From humble beginnings and triumphs on the battlefield during the Civil War to the presidency of the United States, Ulysses S. Grant was a complex man living through one of the nation's most challenging eras. Despite fluctuating views of his legacy over time, his unmatched bravery and his resilience—pulling himself up from adversity—make him a captivating figure in American history. Here are some intriguing facts you may not know about the 18th president of the United States.

1. Ulysses S. Grant's birth name was Hiram Ulysses Grant.

Had you called him Ulysses S. Grant as a child, he wouldn’t have recognized the name. Born Hiram Ulysses Grant in Point Pleasant, Ohio, on April 27, 1822, to Jesse Root Grant, a tanner, and Hannah Simpson Grant, he was known by his middle name as a young boy. According to legend, he disliked the initials H.U.G. However, the name he became known by was a result of a mix-up when Ohio Congressman Thomas Hamer, an old friend of Grant's father, nominated him for West Point in 1839. During the process, his name was mistakenly listed as “Ulysses S. Grant,” with the “S” representing his mother's maiden name, Simpson.

Aware of his modest background, the young Grant accepted the mix-up in his name, and it became permanent. His classmates even adopted it as a nickname, calling him “Sam.” Later, in a letter to his future wife Julia in 1844, Grant humorously wrote, “Find some name beginning with ‘S’ for me, You know I have an ‘S’ in my name and don’t know what it stands for.” (By the way, Grant wasn’t the only president with an odd middle name—Harry S. Truman also had just an “S.”)

2. Ulysses S. Grant despised the West Point uniform.

Although Grant's father believed that enrolling him in the prestigious West Point would create opportunities, young Grant found the school's decorum intolerable. He was often seen as unkempt, earning demerits for his sloppy uniform—an issue that would follow him later as commander of the Union Army during the Civil War.

In a letter from 1839, the 17-year-old Grant wrote to his cousin, McKinstry Griffith, stating that he “would laugh at my appearance” if he saw himself in his uniform: “My pants set as tight to my skin as the bark to a tree.” He added, “If I bend over, they are very apt to crack with a report as loud as a pistol,” and joked, “If you were to see me from a distance, the first question you would ask would be ‘Is that a fish or an animal?’”

3. Ulysses S. Grant met his wife, Julia, through her brother.

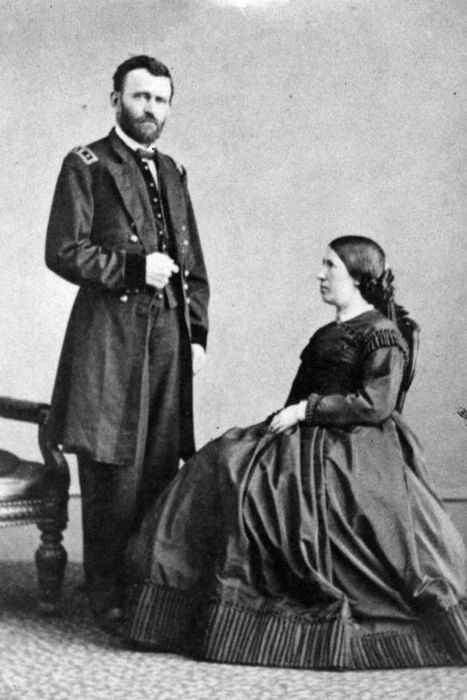

Ulysses and Julia Grant. | Hulton Archive/GettyImages

Ulysses and Julia Grant. | Hulton Archive/GettyImagesJulia Boggs Dent was born on January 26, 1826, in St. Louis. A passionate reader and talented pianist, she also possessed a natural flair for the arts.

Julia was introduced to Ulysses by her brother Fred, who attended West Point with the future general. In a letter to his sister, Fred described Grant as “pure gold.” Fred also mentioned Julia to Grant, leading to their first meeting. After graduating from West Point in 1843 as a brevet second lieutenant, Grant began visiting the Dent family at their home near St. Louis in 1844, and he proposed to Julia a few months later. They kept their engagement a secret until 1845 when Grant formally sought her father's approval to marry. Although Mr. Dent consented, the outbreak of the Mexican-American War delayed their wedding, and the couple didn’t marry until 1848.

4. Ulysses S. Grant fought alongside another future U.S. president: Zachary Taylor.

Grant served in the Mexican-American War under General Zachary “Old Rough and Ready” Taylor, who would later become the 12th president of the United States in 1849.

Taylor led Grant into his first major military engagement at the Battle of Palo Alto, alongside thousands of troops. Grant went on to participate in almost every significant battle of the war. As regimental quartermaster during the Battle of Monterrey, Grant rode through intense Mexican gunfire to deliver a message requesting desperately needed ammunition after Taylor’s troops ran out of bullets.

In his memoirs, Grant reflected on how he admired Taylor for the same qualities that would define Grant’s own leadership style, including Taylor’s ability to “express what he wanted to say in the fewest well-chosen words” and how Taylor’s approach “[met] the emergency without reference to how they would read in history.”

5. Ulysses S. Grant wasn’t a military figure when the Civil War began.

Although Grant was hailed as a hero after the Mexican-American War, he was far removed from such accolades when the Civil War began in 1861. After resigning from the military, Grant struggled with several civilian jobs, including stints as a farmer, real estate agent, and rent collector. He even resorted to selling firewood on the streets of St. Louis. At the time the Civil War broke out, Grant was working in his father’s leather store in Galena, Illinois.

6. Ulysses S. Grant turned setbacks in his civilian career into military triumphs.

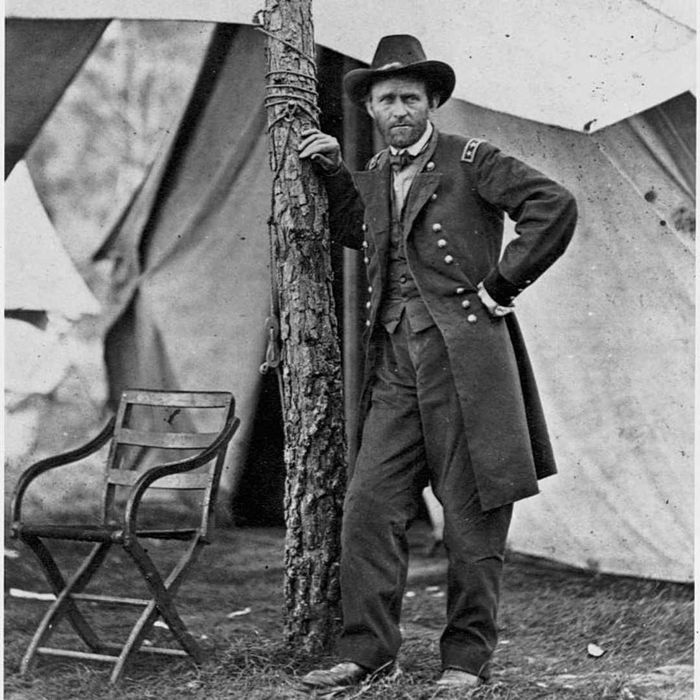

Ulysses S. Grant in uniform. | Library of Congress/GettyImages

Ulysses S. Grant in uniform. | Library of Congress/GettyImagesFueled by a deep sense of patriotism at the start of the Civil War, Grant tried to enlist but was initially turned down for military service due to his past mistakes.

Illinois Congressman Elihu Washburne took a gamble on Grant, arranging a meeting with Illinois Governor Richard Yates. As a result, Grant was appointed to lead a volunteer regiment, whipping them into shape and eventually earning a promotion to brigadier general of volunteers. (Grant later returned the favor to Washburne by appointing him U.S. Secretary of State and later, Minister to France.)

Grant is recognized for leading the Union to two major victories at Fort Henry and Fort Donelson, earning him the moniker 'Unconditional Surrender Grant.'

7. Ulysses S. Grant nearly lost his position at Shiloh.

After his wins at Fort Henry and Fort Donelson, Grant faced fierce criticism for his command during the Battle of Shiloh, one of the deadliest battles in American history up until that time. Although the Union ultimately triumphed, the battle resulted in a staggering 23,746 casualties—most of them Union soldiers.

On April 6, 1862, Grant’s army was stationed, awaiting reinforcements from General Don Carlos Buell’s troops, as they planned to take a critical Confederate railroad junction and transportation hub in Corinth, Mississippi. However, before Buell’s forces could arrive, Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston’s army launched a surprise attack. Caught off guard, Union soldiers were pushed back for most of the day, nearly being overwhelmed, until Buell’s reinforcements arrived.

Though the Union ultimately secured the victory, Grant’s unpreparedness led to calls for his dismissal in the aftermath of the battle.

Pennsylvania politician Alexander McClure visited President Abraham Lincoln at the White House to advocate for Grant’s removal, stating, “I appealed to Lincoln for his own sake to remove Grant at once, and, in giving my reasons for it, I simply voiced the admittedly overwhelming protest from the loyal people of the land against Grant’s continuance in command.” McClure later recalled Lincoln’s response: “I can’t spare this man; he fights.”

Despite rumors suggesting his blunder at Shiloh was due to intoxication, Grant reassured Julia in a letter dated April 30, 1862, saying, “I’m sober as a deacon no matter what is said to the contrary.”

8. Ulysses S. Grant’s subsequent battles, such as Vicksburg and Chattanooga, cemented his reputation as a military leader.

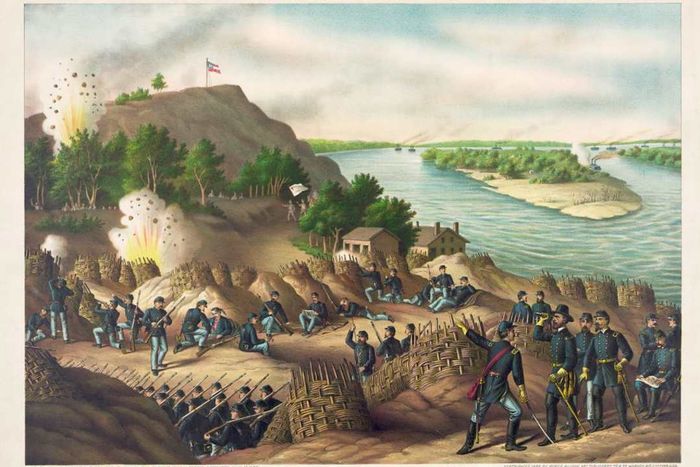

An illustration of the siege of Vicksburg during the Civil War | Historica Graphica Collection/Heritage Images/Getty Images

An illustration of the siege of Vicksburg during the Civil War | Historica Graphica Collection/Heritage Images/Getty ImagesFor his next major task, Grant initiated a six-week siege on the Confederate stronghold of Vicksburg, Mississippi, aiming to capture the city from General John C. Pemberton. The Union bombardment was so intense that many residents of the city were forced to flee their homes and take refuge in caves. The editor of the local Daily Citizen newspaper resorted to printing news on wallpaper. Pemberton eventually surrendered on July 4, 1863.

Later that year, from November 23 to November 25, Union forces decisively defeated the Confederates at the Battle of Chattanooga. Grant, now a major general, orchestrated a three-pronged assault—one section led by Major General William Tecumseh Sherman—against entrenched Confederate positions on Missionary Ridge and Lookout Mountain. The bold strategy paid off, leading to a Union victory.

Thanks to his triumphs, Grant was promoted to lieutenant general in March 1864, with full command over all Union forces. From then on, Grant would report only to the president.

9. Ulysses S. Grant penned the surrender terms at Appomattox.

Despite a final attempt by General Robert E. Lee to rally his weary troops, the Battle of Appomattox Court House ended quickly after Confederate forces were cut off from their last supplies and reinforcements. Lee sent a message to Grant expressing his willingness to surrender, and the two generals met later that afternoon in the front parlor of the Wilmer McLean home on April 9, 1865.

Lee arrived in full military regalia—sash, sword, and all—while Grant, true to form, showed up in his well-worn, mud-streaked field uniform and boots. He then proceeded to write the brief, single-paragraph terms of surrender.

According to the terms, Confederate soldiers and officers were permitted to return home, with officers allowed to keep their horses for agricultural purposes (the National Park Service notes that Grant also directed officers to permit enlisted men to keep their animals) and retain their sidearms. Grant also ordered Union rations to be provided to the famished Confederate troops.

When news of the surrender reached Union forces nearby, gun salutes rang out, but Grant, mindful of the devastating toll of the war, issued an order to halt all celebrations. “The war is over,” he declared. “The rebels are our countrymen again; and the best sign of rejoicing after the victory will be to refrain from all field demonstrations.”

10. Ulysses S. Grant was scheduled to be at Ford's Theatre the night President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated.

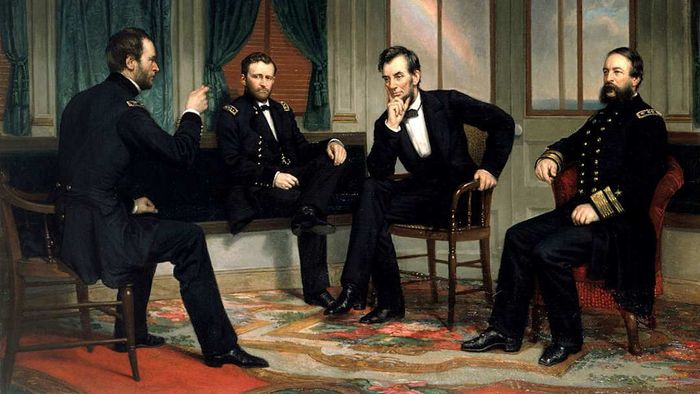

The Peacemakers by George P.A. Healy | Fine Art/GettyImages

The Peacemakers by George P.A. Healy | Fine Art/GettyImagesThe famous general canceled his plans, stating that he and Julia had intended to travel to New Jersey to visit their children instead. (In reality, Julia had a strong dislike for Mary Todd Lincoln and didn’t want to be in her presence. Grant, too, wasn’t particularly keen on the idea.)

Grant was reportedly one of the intended victims in John Wilkes Booth’s plot to assassinate President Lincoln and was supposed to be killed alongside him that evening.

11. Ulysses S. Grant lacked political experience when he became president.

While Grant was hailed as a war hero and had attended cabinet meetings during President Andrew Johnson's Reconstruction, he had little to no political experience when he was nominated for the presidency in 1868. However, given the lingering impact of the Civil War, it was understandable that someone credited with helping preserve the Union would be given a chance at the nation’s highest office.

He won a second term, but his presidency was marred by scandals—including the notorious 1869 Black Friday, where two financiers attempted to corner the nation’s gold market while Grant’s Treasury Department sold gold at weekly intervals to reduce the national debt. Additionally, his struggles with party politics further hindered his administration.

In his farewell message to Congress, Grant admitted, “It was my fortune, or misfortune, to be called to the office of Chief Executive without any previous political training. Under such circumstances it is but reasonable to suppose that errors of judgment must have occurred.”

12. Ulysses S. Grant faced a series of unfortunate events after his presidency.

Despite the long-standing unwritten rule against serving more than two terms—until the 22nd Amendment formalized the limit in 1951—Grant made an attempt to run for a third term four years after leaving office. However, he failed to garner enough support at the Republican convention, and James Garfield went on to win both the nomination and the presidency.

After stepping away from politics, Grant invested his personal savings and became a partner in a financial firm, which also involved his son. Unfortunately, the firm collapsed in 1884 when one of the partners defrauded investors through fraudulent loans, leading to bankruptcy.

Unfortunately, things didn’t improve for Grant. Shortly after, he was diagnosed with throat cancer. In a bid to settle his growing debts and secure his family’s future, Grant began writing his memoirs. He signed a deal with none other than Mark Twain, author of *Tom Sawyer* and *Huckleberry Finn*, whose publishing house, Charles L. Webster & Company, was in desperate need of a success.

13. Ulysses S. Grant passed away on July 23, 1885.

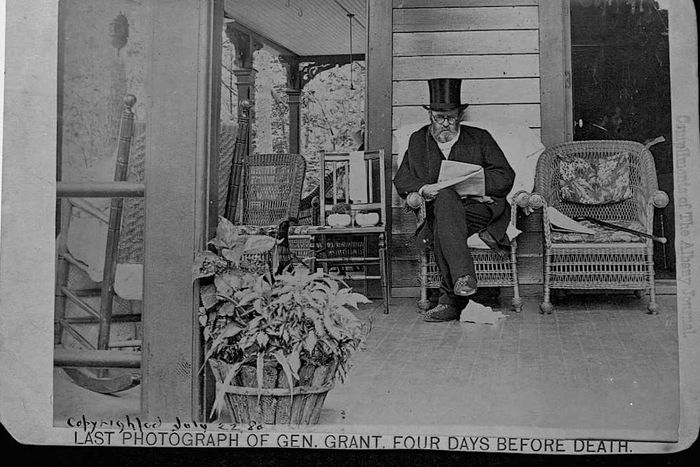

Ulysses S. Grant, four days before his death. | Library of Congress/GettyImages

Ulysses S. Grant, four days before his death. | Library of Congress/GettyImagesGrant completed his memoirs just before his death. The two-volume *Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant* became both a critical and commercial hit, bringing in royalties of about $450,000 for his wife, Julia (which is equivalent to more than $10 million today).

Grant's final resting place is a grand 150-foot-high tomb located in New York City. Designed by John Duncan, this mausoleum is the largest of its kind in North America. The inscription on the exterior reads, “Let us have peace.” After Grant's passing, Julia was laid to rest beside him in 1902.

This article was first published in 2019 and has since been updated in 2022.