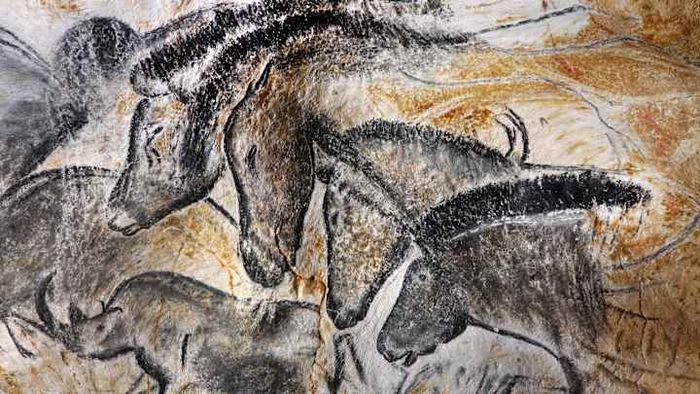

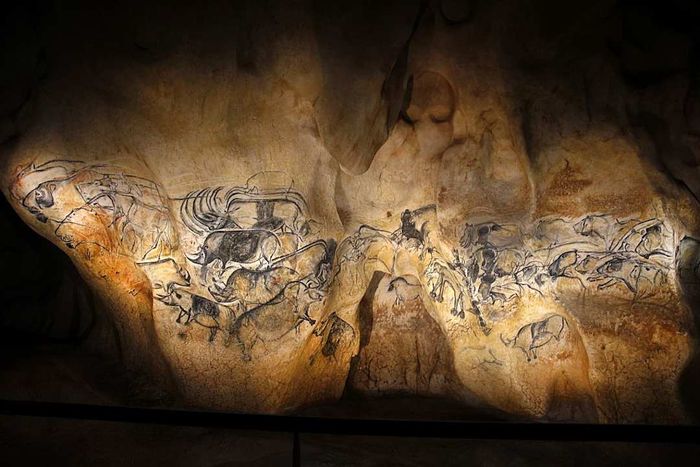

Unearthed unexpectedly in 1994, the ancient murals within France's Chauvet Cave rank among the earliest and most exquisite examples of figurative art in human history. Created approximately 36,000 years ago, these masterpieces vividly portray animals in motion, appearing to run, crawl, and play across the cave's walls. One breathtaking section spans 49 feet, showcasing 50 dynamic depictions of horses, lions, and reindeer. The artistry was so captivating that filmmaker Werner Herzog dedicated a documentary to it. Below are additional insights into these remarkable paintings.

Three local adventurers were responsible for uncovering the Chauvet Cave paintings.

On December 18, 1994, French explorers Jean-Marie Chauvet, Éliette Brunel Deschamps, and Christian Hillaire were investigating the Pont d’Arc caves in southern France. Noticing a faint breeze emanating from a pile of rocks, they cleared the debris and discovered an opening leading to a vast chamber. Inside, their headlamps revealed ancient handprints and a mammoth painted in red ochre. Realizing the significance of their find, they knew they had made a groundbreaking archaeological breakthrough.

An underground river was responsible for shaping the cave.

A detailed reproduction of the Chauvet Cave's interior. | Patrick Aventurier/GettyImages

A detailed reproduction of the Chauvet Cave's interior. | Patrick Aventurier/GettyImagesChauvet Cave, along with numerous other caves and gorges in the Ardèche region, was carved out by underground rivers flowing through limestone hills. Stretching approximately 1300 feet, the cave features 14 chambers branching from the main room, known as the Chamber of the Bear Hollows—the first area discovered by Chauvet, Brunel Deschamps, and Hillaire. While this chamber, near the entrance, lacks artwork due to flooding, the deeper sections, such as the Hillaire Chamber, Red Panels Gallery, Skull Chamber, Megaloceros Gallery, and End Chamber, are richly adorned with paintings.

The artists behind the Chauvet Cave paintings belonged to the Aurignacian culture.

The Aurignacians, Europe's earliest anatomically modern humans, thrived during the Upper Paleolithic era, also known as the Old Stone Age, spanning from 46,000 to 26,000 years ago. (The term Aurignacian also denotes this historical period.) This culture is renowned for pioneering figurative art, creating engravings with a specialized stone tool called a burin, crafting tools from bone and antler, producing jewelry, and inventing some of the earliest musical instruments.

Beyond the Chauvet Cave paintings, Aurignacian artifacts, including animal and human figurines, have been unearthed across Europe. For instance, the Hohle Fels cave in southwestern Germany yielded the oldest-known Venus statuette, dating back 40,000 to 35,000 years, as well as ancient bone flutes. In Southeast Asia, a cave on Sulawesi Island houses the oldest-known figurative painting, estimated to be at least 51,000 years old.

Chauvet Cave was frequented by ancient humans during two distinct periods, separated by millennia.

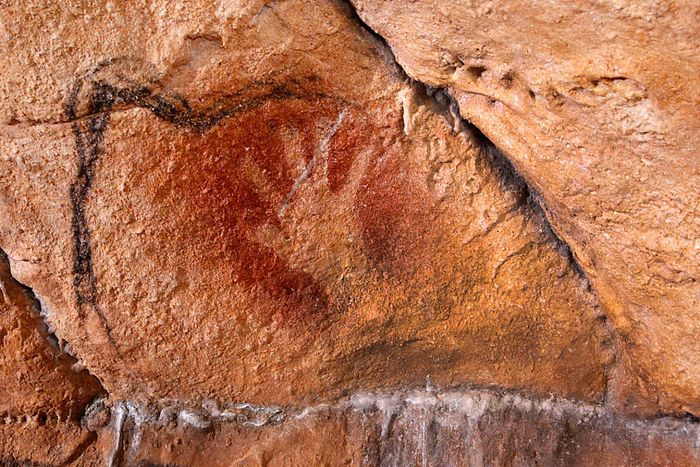

A reproduction showcasing one of the numerous stenciled handprints left by the cave's artists. | Patrick Aventurier/GettyImages

A reproduction showcasing one of the numerous stenciled handprints left by the cave's artists. | Patrick Aventurier/GettyImagesPaleontologist Michel-Alain Garcia, in Chauvet Cave: The Art of Earliest Times, notes that radiocarbon dating of organic materials indicates human activity in Chauvet Cave during two distinct eras. The first, around 36,500 years ago during the Aurignacian period, saw the creation of most cave paintings. Artists used wood for light and charcoal for drawing. After a hiatus of 5,000 to 6,000 years, during which cave bears occupied the space, humans returned during the Gravettian period (31,000 to 30,000 years ago), leaving footprints, torch marks, and charcoal but no new artwork.

The paintings feature depictions of 14 different animal species.

Cave lions, mammoths, and woolly rhinoceroses dominate the Chauvet Cave artwork, reflecting species that once roamed Europe alongside the Aurignacians but are now extinct. These, along with cave bears, account for 65 percent of the depicted animals. Other species include bison, horses, reindeer, red deer, ibex, aurochs (wild ancestors of cattle), Megaloceros deer (also known as the Irish elk), musk ox, panthers, and an owl. The paintings stand out for capturing not just animal forms but also dynamic scenes, such as woolly rhinoceroses clashing horns and lions hunting bison.

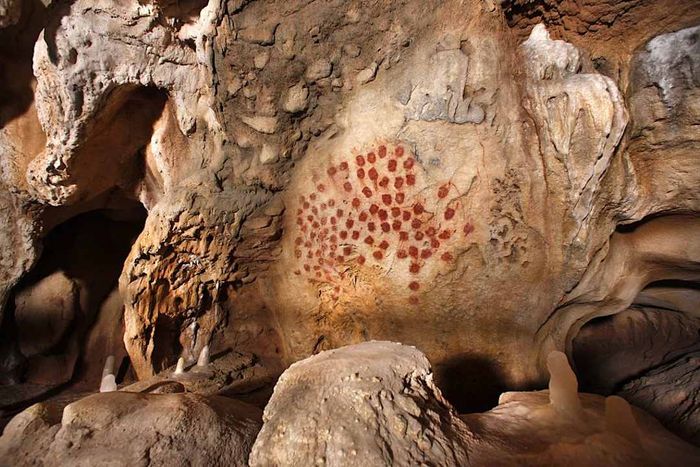

The artwork also includes non-animal motifs.

A reproduction of an abstract design created with red daubed paint discovered in Chauvet Cave. | Patrick Aventurier/GettyImages

A reproduction of an abstract design created with red daubed paint discovered in Chauvet Cave. | Patrick Aventurier/GettyImagesSeveral walls and overhangs in Chauvet Cave's central chambers are adorned with red dots made from human palms and hand stencils. In the cave's deepest sections, five triangular depictions of a woman’s pubic area are etched into the walls, and a drawing resembling the lower body of Paleolithic Venus figurines is found on a stalactite-like rock. Anthropologists remain uncertain about their symbolic meaning.

Footprints belonging to a prehistoric child were uncovered in Chauvet Cave.

A 230-foot-long trail of footprints was discovered in the cave's Gallery of the Crosshatching, preserved in soft clay. Researchers compared the prints to modern European feet and concluded they likely belonged to a young boy approximately 4.5 feet tall. The prints were dated using torch marks on the gallery ceiling, which the child used to wipe his torch, possibly to mark his return path. Charcoal fragments found nearby date the footprints to between 31,430 and 25,440 years ago.

The child may have been accompanied by a domesticated dog.

The footprints of the adolescent boy are close to those of a large canid, possibly a wolf. Upon closer inspection, Garcia observed that the middle digit was shorter than that of a wolf, a characteristic more aligned with a domesticated dog. However, in the 1990s, when Garcia made this discovery, the oldest confirmed fossil evidence of domesticated dogs only dated back 14,200 years.

A 2017 study, expanding on prior research, analyzed the genomes of three Neolithic dogs alongside over 5000 modern wolves and dogs. The findings suggested that dogs and wolves diverged genetically between 41,500 and 36,900 years ago, with a second split between eastern and western dogs occurring between 23,900 and 17,500 years ago. This places the domestication period between 40,000 and 20,000 years ago—coinciding with the time the Aurignacian child and his potential canine companion roamed Chauvet Cave.

The cave served as a refuge for bears.

A haunting replica of a cave bear’s skull, intentionally placed on a boulder within Chauvet Cave. | Patrick Aventurier/GettyImages

A haunting replica of a cave bear’s skull, intentionally placed on a boulder within Chauvet Cave. | Patrick Aventurier/GettyImagesCave bears, larger than today’s grizzlies, inhabited Chauvet Cave for millennia before humans began painting there. They left claw marks on the walls and numerous tracks and footprints on the cave floor. In the Chamber of the Bear Hollows, over 300 sleeping hollows and dozens of bear tracks were discovered, dating to a time after humans had ceased visiting. Approximately 2500 cave bear bones and 170 skulls were found scattered throughout the cave. During initial explorations in the 1990s, scientists discovered a cave bear skull deliberately placed on a large stone in a deep chamber, suggesting human intervention.

Wolves were also frequent inhabitants of the cave.

The Brunel Chamber, located south of the Chamber of the Bear Hollows, contained numerous wolf prints, indicating significant activity by these pad-footed carnivores. Bear prints overlay the wolf tracks, implying that bears arrived after the wolves.

The cave was home to more than just large carnivores—it was essentially a prehistoric zoo. Alongside wolf, ibex, and bear bones, prehistorian Jean Clottes identified remains of foxes, martens, roe deer, horses, birds, rodents, bats, and reptiles. Fossilized wolf droppings were also found, suggesting wolves entered the cave in search of carrion.

The purpose and meaning behind the cave paintings remain a mystery.

A precise reproduction of the ice age animal scenes depicted on a large wall within Chauvet Cave. | Patrick Aventurier/GettyImages

A precise reproduction of the ice age animal scenes depicted on a large wall within Chauvet Cave. | Patrick Aventurier/GettyImagesWhile the purpose of the Chauvet Cave paintings remains unclear, certain aspects of the artwork may provide insights. Researchers have observed that the main animals depicted—cave bears, lions, mammoths, and rhinoceroses—were not hunted by the Aurignacians for food, suggesting the paintings may not have been created to ensure successful hunts.

A 2016 study suggested that the Chauvet Cave artists might have been documenting real events. Jean-Michel Geneste and his team proposed that a spray-like pattern in the Megaloceros Gallery accurately represented a volcanic eruption in the nearby Bas-Vivaris region, occurring between 40,000 and 30,000 years ago. If confirmed, this would make the Chauvet Cave artwork the oldest known depiction of volcanic activity, surpassing a 9000-year-old mural in Turkey by 28,000 years.

Werner Herzog was deeply moved upon entering Chauvet Cave.

In 2010, filmmaker Werner Herzog joined researchers deep inside the cave system to create his documentary Cave of Forgotten Dreams. With a grandfather who was an archaeologist and a personal passion for cave art—Herzog once worked as a ball boy to afford a book on the subject—he described the experience as profoundly awe-inspiring. “Even though I had seen photos, nothing prepared me for the overwhelming impact,” Herzog told The A.V. Club in 2011. “The mystery of why these paintings were made in complete darkness, far from the entrance, remains unanswered.”

A life-sized replica of the Chauvet Cave paintings is accessible to the public.

After the Lascaux cave paintings near Pont d’Arc suffered damage from visitor exhalations following their public opening in 1948, scientists took swift action to protect Chauvet Cave’s fragile artwork. Access is now restricted to scholars during limited periods. However, a detailed replica, the Caverne du Pont d’Arc, opened in 2015 near the original site. This recreation captures not only the stunning paintings but also the cave’s atmosphere, including its temperature, humidity, dim lighting, and distinctive odor.