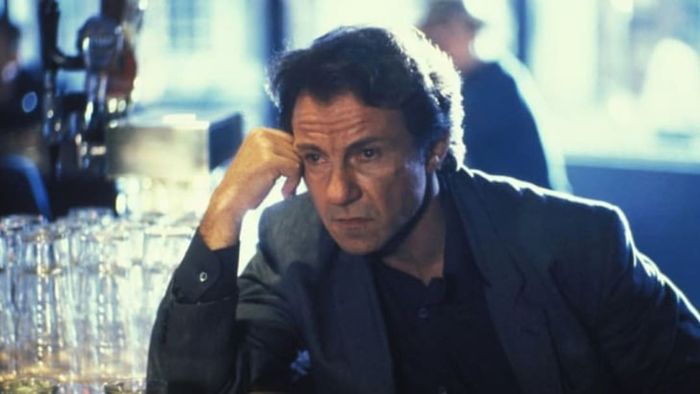

Bad Lieutenant may face numerous criticisms, but misleading its audience isn’t one of them. Harvey Keitel’s unnamed protagonist is undeniably a terrible, terrible lieutenant: corrupt, morally bankrupt, drug-dependent, reckless, and lecherous, even while on duty. (One can only imagine his off-duty antics!)

Abel Ferrara’s haunting exploration of a deeply flawed character stirred controversy upon its release 25 years ago today. Rated NC-17 for its explicit nudity (including the infamous shot of Lil’ Harvey), disturbing sexual violence, and unflinching portrayal of drug abuse, the film leaves a lasting impact. Here’s some behind-the-scenes trivia to help you process it.

1. THE CALM WOMAN WHO ASSISTS THE LIEUTENANT IN FREEBASTING HEROIN IS THE FILM’S WRITER.

Zoë Tamerlis Lund, who appeared in Abel Ferrara’s revenge-driven thriller Ms. 45 (1981) at just 17, co-wrote Bad Lieutenant with Ferrara, though she consistently claimed sole authorship. "I wrote this alone," she stated. "Abel is a brilliant director, but not a screenwriter." She also mentioned that she "wrote every word of that screenplay," despite the film’s heavy reliance on improvisation. Lund, a musical prodigy and unapologetic heroin user who later switched to cocaine in the mid-1990s, led a tragic life, passing away from heart failure in 1999 at 37.

2. CHRISTOPHER WALKEN WAS ORIGINALLY CAST IN THE LEAD ROLE.

After starring in Ferrara’s King of New York (1990), Christopher Walken was slated to play the titular role in Bad Lieutenant but withdrew just weeks before filming. Ferrara was stunned. "[Walken] said, 'I don’t think I’m right for it,' which is fine, unless it’s three weeks before shooting," Ferrara recalled. "It left me in terminal shock." Harvey Keitel stepped in (though not without challenges; see below), and editor Anthony Redman believed Keitel was a superior fit. "Chris is too refined for the part," he said. "Harvey is not."

3. HARVEY KEITEL’S FIRST IMPRESSION OF THE SCRIPT WAS LESS THAN ENTHUSIASTIC.

"When we first handed Keitel the script, he read a few pages and tossed it in the trash," Ferrara recalled. Keitel’s version was more tactful. As he told Roger Ebert, "I read a portion and thought, 'I’m not doing this.' Then I reconsidered, 'How often do I get a lead role? Maybe I can find something worthwhile.' When I reached the part about the nun, I understood Abel’s vision."

4. THE FILM WAS INITIALLY ENVISIONED AS A COMEDY.

Lionsgate Home Entertainment

Lionsgate Home Entertainment"I always saw it as a comedy in my mind," Ferrara remarked. He pointed out the scene where the Lieutenant stops the teenage girls as an example of how Christopher Walken would have approached it, contrasting it with Harvey Keitel’s interpretation. "The plan was for the Lieutenant to end up dancing in the streets with the girls at sunrise, wearing his gun belt and hat, with the radio playing. But Harvey transformed it into something entirely different." And he certainly did.

5. THE TEENAGE GIRLS SCENE INCLUDED A REAL-LIFE DETAIL THAT MADE IT EVEN MORE UNNERVING.

One of the girls was Keitel’s actual babysitter. Ferrara recalled, "I asked him, 'Are you sure you want to do this with your nanny?' He replied, 'Yeah, I want to experiment with something.'"

6. A SIGNIFICANT PORTION OF THE FILM WAS SHOT GUERRILLA-STYLE.

Ferrara, like many indie directors working with tight budgets, often skipped permits. "We didn’t have permits for any of this," editor Anthony Redman revealed. "We just showed up and started filming." For instance, the scene where the Lieutenant stumbles through a lively nightclub was shot in a real, fully operational club during its busiest hours.

7. MUCH OF THE DIALOGUE AND ACTION WERE IMPROVISED.

The initial script was only 65 pages, which would have resulted in a 65-minute film. "It left plenty of room for improvisation," producer Randy Sabusawa explained, "but the core ideas were clear and well-defined."

Script supervisor Karen Kelsall found managing the script challenging. "Abel didn’t follow the script closely," she said. "He used it mainly to secure funding, and then treated it like the daily news—constantly changing, even mid-scene." Ferrara defended the script’s brevity, stating, "The expectation of a 90-page script is absurd."

8. THERE WERE ADDITIONAL CONCEPTS THAT NEVER MADE IT INTO THE FILM.

Ferrara mentioned a scene that, for him, perfectly captured the essence of the movie—though it was never filmed. In it, the Lieutenant robs an electronics store, leaves, and later receives a call about the robbery. He responds as an officer (unrecognized by the store staff), takes a statement, walks out, and tosses the statement in the trash. "That, to me, is the Bad Lieutenant," Ferrara explained.

9. THE BASEBALL PLAYOFF SERIES WAS ENTIRELY FICTIONAL.

The Mets and Dodgers have only faced off once for the National League championship, in 1988 (with the Dodgers winning and eventually claiming the World Series). To fit Ferrara’s narrative—where the Mets overcome a 3-0 deficit to win the pennant—he fabricated the storyline. Real footage from Mets-Dodgers games, including Darryl Strawberry’s three-run homer from a 1991 game, was used, paired with fictional commentary. The statistics, however, were accurate: no team had ever rallied from a 3-0 deficit in a best-of-seven series before. (This feat was later achieved by the 2004 Red Sox.)

10. THEY RECEIVED ASSISTANCE FROM A COP WHO HAD SOLVED A SIMILAR CASE.

The horrifying crime central to the film (which we won’t elaborate on) was based on a real 1981 case that mayor Ed Koch described as "the most heinous crime in New York City’s history." Bo Dietl, the street cop who solved the case, served as a consultant for Ferrara and even appeared on-screen as one of the detectives in the Lieutenant’s circle.

11. THEY VANDALIZED THE CHURCH WITH AS MUCH RESPECT AS POSSIBLE.

Production designer Charles Lagola ensured the church’s altar and other surfaces were covered with plastic wrap before painting graffiti and other defacements onto the plastic.

12. THE THEATRICAL RELEASE WAS RATED NC-17, WHILE A TONED-DOWN R-RATED VERSION WAS CREATED FOR HOME VIDEO.

Since Blockbuster and other retailers refused to stock NC-17 or unrated films, studios often released edited versions. (See: Requiem for a Dream.) The less explicit version of Bad Lieutenant was trimmed by five minutes and 19 seconds, removing portions of the rape scene, drug injection sequence, and much of the car interrogation.

13. THE SO-CALLED "SEQUEL" WAS COMPLETELY UNRELATED, AND FERRARA DID NOT ENDORSE IT.

First Look International

First Look InternationalFilm enthusiasts were puzzled in 2009 when Werner Herzog directed Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans, featuring Nicolas Cage. While it appeared to be a sequel or remake, it had no ties to Ferrara’s original film aside from sharing producer Edward R. Pressman. Herzog admitted he had never seen Ferrara’s version and wanted to alter the title (Pressman refused). Ferrara, never one to hold back, initially wished ill upon everyone involved. The two directors eventually met at the 2013 Locarno Film Festival in Switzerland, where Herzog addressed the controversy, and Ferrara calmly shared his grievances.

Additional sources: DVD interviews with Abel Ferrara, Anthony Redman, Randy Sabusawa, and Karen Kelsall.