Think taxidermy is just about preserving and stuffing animals? There’s far more to it. From the pioneering work of William Hornaday to the groundbreaking contributions of Carl Akeley, taxidermy has evolved into both a scientific discipline and an intricate form of art. It involves careful measurement, photography, and anatomical study of the animals to create lifelike representations. Keep reading for 12 surprising insights into the history, development, and craft of taxidermy.

1. The term taxidermy originates from the Greek words taxis and derma.

These words translate to “arrangement” and “skin,” respectively. Some claim that the first person to use the word taxidermy was Louis Dufresne from the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris, who referenced it in his 1803 book Nouveau Dictionnaire d’Histoire Naturelle. However, according to Merriam-Webster, the term first appeared at least three years earlier in an ornithological work by zoologist François Marie Daudin.

2. Mummies Are Not Considered 'True Taxidermy.'

Egyptian cat mummy. | Print Collector/GettyImages

Egyptian cat mummy. | Print Collector/GettyImagesHumans have been preserving animals for millennia, as seen with the mummified cats of ancient Egypt. However, as conservator Amandine Péquignot explains in The History of Taxidermy: Clues for Preservation [PDF], these ancient specimens “should not be classified as true taxidermy.” The reason lies in the different aims and methods behind the two practices: “Mummies were made in a religious context, while taxidermy developed from a scientific curiosity about the natural world.”

3. The Rise of Modern Taxidermy Began in England in the Early 19th Century.

Children view the taxidermy work of Walter Potter circa 1950. | John Pratt/GettyImages

Children view the taxidermy work of Walter Potter circa 1950. | John Pratt/GettyImagesAs Péquignot explains, taxidermy began to take shape in the 16th century, when Europeans first started mounting animal skins and developed preservation methods and chemicals. Over time, these techniques improved, and by the 19th century, taxidermy had become firmly established in scientific communities.

In 1851, the Great Exhibition in London showcased around 100,000 objects from over 15,000 contributors, including a significant number of taxidermy pieces. The Indian exhibit featured a taxidermied elephant (though it was actually an African elephant from a nearby museum). Among the contributions was J.A. Hancock’s taxidermy, which the Official Catalogue claimed “would go far towards raising the art of taxidermy to a level with other arts that had previously been more highly regarded.” And it did—following the exhibition, taxidermy became a widely enjoyed hobby; even a young Theodore Roosevelt took lessons. By then, Victorians began anthropomorphizing their taxidermy, dressing stuffed animals in clothing and incorporating them into tableaus like those by Walter Potter. They even created animals with extra heads or limbs.

4. Taxidermy Played a Role in Captain James Cook’s Expeditions.

Captain James Cook. | Print Collector/GettyImages

Captain James Cook. | Print Collector/GettyImagesCaptain James Cook embarked on several exploratory journeys across the South Pacific, during which taxidermy was used to preserve animal specimens. One notable instance, according to Royal Museums Greenwich, involves Cook supposedly bringing the first kangaroo skin to London in 1771, which was reportedly killed by a dog belonging to naturalist Sir Joseph Banks. Bird specimens collected on Cook's expeditions can now be viewed at institutions like the UK’s Natural History Museum.

5. Charles Darwin Was Taught Taxidermy by a Formerly Enslaved Guyanese Man Named John Edmonstone.

John Edmonstone had learned the craft from naturalist Charles Waterton, who brought him along on expeditions. Edmonstone charged Darwin a guinea an hour for his services; Darwin later wrote to his sister that Edmonstone “earned his living by stuffing birds, which he did exceptionally well.” Without the taxidermy skills Edmonstone taught him, Darwin might never have secured a job aboard the HMS Beagle.

6. In Early Taxidermy, Creatures Were Stuffed with Sawdust and Rags, Often Ignoring Anatomical Accuracy.

The dodo. | Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images

The dodo. | Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty ImagesAs a result, these early mounts were frequently distorted. In fact, the way these mounts were created led to a skewed perception of extinct animals like the dodo for many years. (The only soft tissue specimen of a dodo, housed in the collections at the UK’s Oxford University Museum of Natural History, continues to reveal new insights about the bird.) Today, taxidermists can purchase mannequins to model the desired pose and stretch the skin over them, or they can revert to old methods, such as the Victorian practice of shaping the body with string.

7. People Initially Believed the First Platypus Specimen Was a Taxidermy Fraud.

When Captain John Hunter sent the first platypus pelt and sketch back to England in 1798, many dismissed it as a hoax, thinking someone had attached a duck’s bill to a beaver’s body. George Shaw, the author of The Naturalist's Miscellany: Or, Coloured Figures Of Natural Objects; Drawn and Described Immediately From Nature, is said to have used scissors to check the skin for stitches.

8. The First American Taxidermy Competition Was Held by the American Society of Taxidermists in 1880.

The top prize went to taxidermist William Temple Hornaday for his piece A Fight in the Tree-Tops, which portrayed two male Bornean orangutans fighting over a female. As noted by Melissa Milgrom in her book Still Life: Adventures in Taxidermy, this scientifically accurate scene shifted the purpose of taxidermy—prompting other taxidermists to prioritize accuracy in their mounts as well.

9. Many Dioramas at Natural History Museums Feature Animals in Carefully Recreated Natural Habitats.

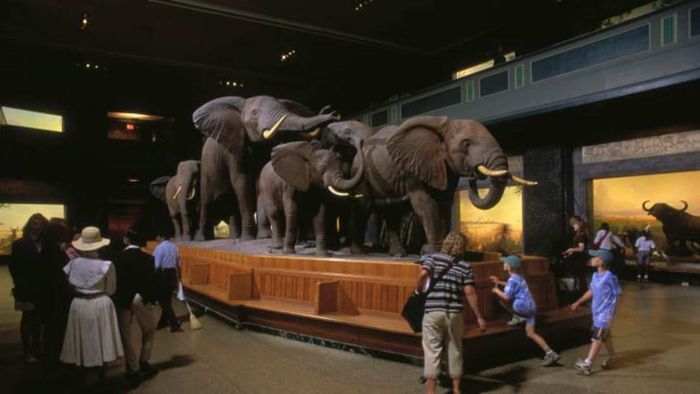

The Akeley Hall of African Mammals. | George Steinmetz/Getty Images

The Akeley Hall of African Mammals. | George Steinmetz/Getty ImagesCarl Akeley, after whom the Akeley Hall of African Mammals at New York's American Museum of Natural History is named, created the first habitat diorama in America, featuring muskrats, in 1889 for the Milwaukee Public Museum.

Akeley's meticulous process of preserving a single elephant was recounted by his wife in her memoir, The Wilderness Lives Again. Milgrom summarizes this in Still Life:

“After the elephant was shot in the wild, he covered it with a tarp to delay decomposition. He photographed it for reference and took precise measurements using a tape measure and calipers, adjusting for changes that occur in a dead animal compared to a living one, such as deflated lungs, a limp trunk, and slack muscles. He then encased the skull and leg bones in plaster and crafted a death mask of the face to capture its fine muscle details. ... Akeley skinned animals with the precision of a Park Avenue plastic surgeon. His incisions were made so that future seams would disappear when the animal was reassembled. The legs were cut from the inside; the back was sliced along the spine; the head was cast and removed. Once skinned, the elephant was fleshed out ... Akeley and his team took four to five days to carefully remove and prepare the 2,000-pound hide using small knives to prevent any damage to the skin.”

At the museum, Akeley tanned the hide over 12 weeks, turning the 2.5-inch thick skin into quarter-inch leather. He outlined the shape of the elephant on the floor and constructed its internal frame using steel, wood, and the elephant's bones. This frame was then covered with wire mesh and clay, which Akeley sculpted to replicate the elephant's muscles. After fitting the skin onto this form and ensuring the clay perfectly matched “every fold and wrinkle,” as Milgrom notes, he cast the form in plaster to create a lightweight mannequin, which he eventually used to stretch the skin over. This process was how he created the elephants displayed in the Akeley Hall of African Mammals.

In addition to his meticulous attention to detail—he even invented the first portable movie camera to capture animals in their natural habitat for more accurate taxidermy mounts—Akeley was also incredibly tough: On one occasion, he killed a leopard with his bare hands.

10. Arsenic was one of the earliest preservatives used in taxidermy.

During those times, taxidermy competition was intense, with preservation methods varying from one taxidermist to another and often kept secret—some craftsmen even carried their methods to the grave. Fun fact: As a teenager, the future president Theodore Roosevelt, an enthusiastic hunter and nature lover, tried to purchase a pound of arsenic for taxidermy from a store in Liverpool but was turned away. “I was told I would need to bring a witness to prove I wasn’t going to commit murder, suicide, or anything equally dreadful, before I could buy it!” he wrote in his diary. (Apparently, an adult did later vouch for him.)

11. Taxidermy has its own specialized vocabulary.

In the world of taxidermy, a specimen refers to a true-to-life representation of an animal as it appeared in the wild, while a trophy could be something like a deer head mounted on a wall.

12. Taxidermy competitions feature a category known as “Re-Creations.”

As Milgrom explains, in these categories, taxidermists are tasked with creating an animal without using any of its original body parts—such as crafting an eagle from turkey feathers, or making a life-like panda out of bearskin—or even attempting to recreate extinct species using scientific data.

13. Louis XV’s rhinoceros was preserved through taxidermy.

When the rhino that belonged to Louis XIV and Louis XV was stabbed to death by a revolutionary in 1793, its hide was varnished and stretched over a wooden hoop frame. At the time, it was the largest animal ever to undergo a modern taxidermy process. The skin is now on display at the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris, while its bones are displayed separately.