For nearly 260 years, Guinness has been a cornerstone of Irish pub culture. Given its rich history, the Guinness Storehouse Archives—accessible to the public—are brimming with fascinating relics that reveal extraordinary tales. Here are some highlights.

1. THE DUBLIN BREWERY LEASE WAS SET FOR 9000 YEARS.

In 1759, Arthur Guinness, the founder, secured a lease for a four-acre site at St. James’s Gate in Dublin. The agreement involved an initial payment of £100, yearly rent of £45, and a staggering 9000-year term (yes, you read that correctly). Such extended leases were not unusual during that era: “In Ireland at the time, land ownership was highly unstable,” says Fergus Brady, Guinness Archives Manager. Centuries prior, the British had begun seizing land from the Irish to establish plantations, and these lengthy leases were a strategy to prevent such confiscations. Brady notes, “You’ll find many leases spanning 99 or 999 years. It appears the number nine held a legal significance at the time.”

2. ARTHUR GUINNESS STOOD HIS GROUND WITH A PICKAXE.

In 1775, the Dublin Corporation insisted that Arthur Guinness pay for the spring water supplying his brewery. Guinness countered that his 9000-year lease already covered water rights. When officials arrived to shut off the water, Guinness grabbed a pickaxe and unleashed such a fiery barrage of curses that the intruders were forced to retreat.

3. GUINNESS SENT AGENTS TO COMBAT COUNTERFEITERS.

Guinness Archive, Diageo Ireland

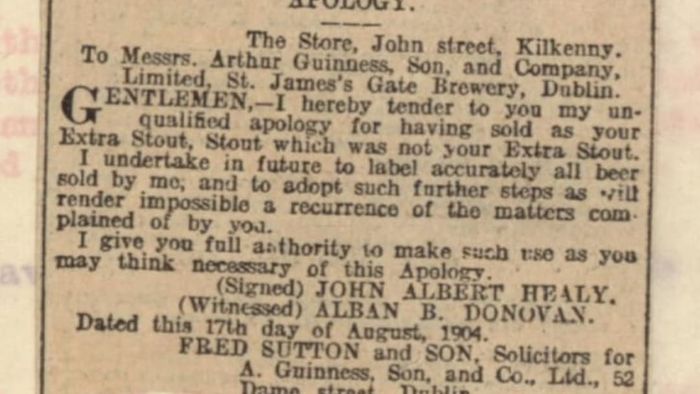

Guinness Archive, Diageo IrelandDuring the 19th century, brand consistency was nonexistent. Guinness didn’t bottle its own beer; instead, it distributed the brew in wooden barrels to publicans, who used their own bottles and labels. Some publicans sold counterfeit or diluted Guinness. To tackle this, the company dispatched agents, known as “travellers,” to gather beer samples for lab testing. “Publicans caught selling fake or tampered Guinness were required to issue public apologies in local or even national newspapers,” explains archivist Jessica Handy.

4. FOR 21 YEARS, GUINNESS EMPLOYED A MAN TO GLOBE-TROT AND SAMPLE BEER.

In 1899, Guinness appointed Arthur T. Shand, an American former brewer, as their “Guinness World Traveller.” This role was arguably one of the most enviable jobs ever. Over two decades, Shand journeyed across the globe, sampling Guinness and evaluating its quality. “His mission was to assess the beer, identify bottlers, analyze competitors, and understand the demographics of Guinness drinkers,” explains Brady. Shand’s travels took him to Australia, New Zealand, Southeast Asia, and Egypt. Brady describes him as “a Guinness sommelier of sorts.”

5. THE GUINNESS HARP LOGO SPARKED A DISPUTE WITH THE IRISH GOVERNMENT.

The Celtic harp, inspired by the 14th-century “Brian Boru Harp” housed at Trinity College, became Guinness’s trademarked logo in 1876. Decades later, when Ireland achieved independence, the Irish Free State adopted the same harp as its national symbol. This created a conflict, as Guinness held the trademark. The Irish government had to devise a solution, which is now visible on Irish Euro coins. On the coin, the harp’s straight edge faces right, while on a Guinness glass, it faces left [PDF].

6. GUINNESS IS SAID TO HAVE SAVED LIVES DURING WARTIME.

The old slogan “Guinness is good for you” might sound like a marketing ploy, but it stemmed from a genuine belief in the beer’s restorative properties. This health claim traces back to 1815, when a cavalry officer injured at the Battle of Waterloo reportedly attributed his recovery to Guinness. For years, the medical community widely endorsed the idea that the stout offered real health benefits—and they weren’t entirely mistaken. “Safe drinking water was scarce at the time,” Handy explains. “Brewing ensured consumers had a safe beverage to drink.”

7. GUINNESS DEVELOPED A SPECIAL BREW FOR RECOVERING PATIENTS.

Guinness Archive, Diageo Ireland

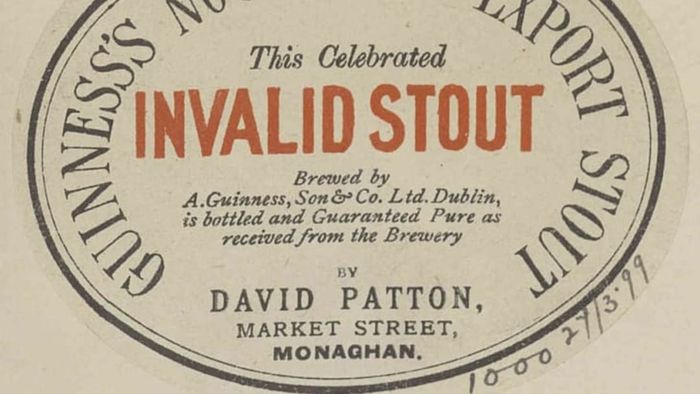

Guinness Archive, Diageo IrelandBetween the 1880s and 1920s, Guinness crafted a unique “Nourishing Export Stout,” also known as “Invalid Stout,” which was richer in sugars, alcohol, and solids, packaged in small one-third pint bottles. “It was common for people to buy a few bottles and keep them as a health tonic, even if they only consumed a small amount,” Handy notes. The company even sought testimonials from doctors, many of whom confirmed they prescribed the beer for various ailments. One physician famously claimed a pint was “as nourishing as a glass of milk.”

8. DOCTORS OFTEN RECOMMENDED GUINNESS TO BREASTFEEDING MOTHERS.

From the 1880s to the 1930s, many doctors considered Guinness a potent galactagogue—a substance that aids lactation. The company distributed bottles to hospitals and even supplied wax cartons of yeast, believed to alleviate skin issues and migraines. Hundreds, if not thousands, of physicians recommended the beer for conditions like influenza, insomnia, and anxiety, as noted by David Hughes in A Bottle of Guinness Please: The Colourful History of Guinness. Brady adds that Guinness continued delivering beer to hospitals into the 1970s.

9. GUINNESS ONCE RELEASED 200,000 MESSAGES-IN-A-BOTTLE INTO THE OCEAN.

The message inside each bottle dropped into the Atlantic Ocean in 1959. | Guinness Archive, Diageo Ireland

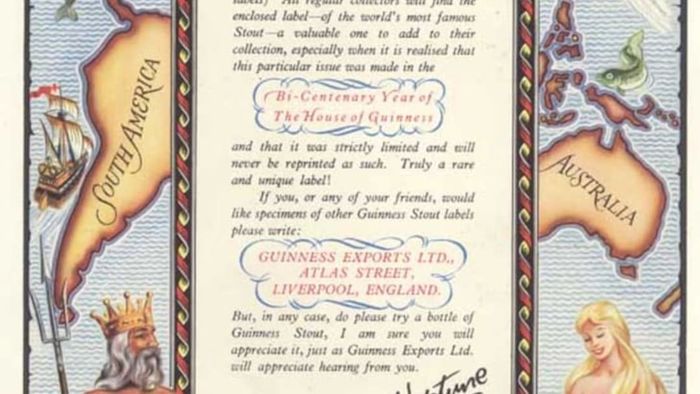

The message inside each bottle dropped into the Atlantic Ocean in 1959. | Guinness Archive, Diageo IrelandIn 1954, Guinness launched 50,000 messages-in-a-bottle into the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans. Five years later, they repeated the campaign, with 38 ships releasing 150,000 bottles into the Atlantic. The first bottle was found near the Azores, off Portugal, just three months later [PDF]. Over the years, bottles have surfaced in California, New Zealand, and South Africa. As recently as last year, one was discovered in Nova Scotia. (Finding one could earn you a trip to the Guinness Storehouse in Dublin.)

10. THE GUINNESS ARCHIVES' PERSONNEL FILES ARE FILLED WITH INCREDIBLE TALES.

The Guinness corporate archives are accessible to the public. Handy shares, “The stories you uncover are astonishing, from accident reports to wild anecdotes like employees bouncing on hop sacks outside the brewery.” This might seem less shocking when you consider that, historically, Guinness workers were allotted two pints of beer daily [PDF].

11. A GUINNESS SCIENTIST REVOLUTIONIZED THE FIELD OF STATISTICS.

If you’ve studied statistics, you’ve likely encountered the Student’s t-test or t-statistic. (It’s a technique for analyzing small sample sizes with unknown standard deviations.) This method was pioneered by William S. Gosset, a Guinness brewer and statistician, while studying malt extract samples. Gosset’s breakthrough not only improved the consistency of Guinness beer but also established a cornerstone of modern statistics: statistical significance.

12. GUINNESS IS SO POPULAR IN AFRICA THAT IT INSPIRED A SUCCESSFUL FEATURE FILM.

Guinness started exporting its beer to Africa in 1827. By the 1960s, it had established breweries in Nigeria, Cameroon, and Ghana. Today, Nigeria reportedly has more Guinness drinkers than Ireland itself. “While people in Ireland, England, and the U.S. associate Guinness with Ireland, in Nigeria, that connection is far less recognized,” Brady explains. The beer is so ingrained in Nigerian culture that a fictional character, Michael Power—a James Bond-esque journalist and crime fighter—became the protagonist of a 2003 film titled Critical Assignment, which was a major box office success. (Naturally, the film includes branding moments, with Michael Power seen enjoying a pint of Guinness.)

13. USING NITROGEN TO DISPENSE BEER WAS ONCE SEEN AS ABSURD.

In the 1950s, Guinness scientist Michael Ash was assigned to tackle the “draft problem.” At the time, serving a draft pint of Guinness was overly complex, and the company was losing ground to draft lagers in Britain that used CO2 for easy dispensing. “Stout was too volatile for CO2 alone,” Brady notes. “Ash dedicated four years to solving the issue, working tirelessly day and night, becoming somewhat reclusive. Many at the brewery mocked the project, calling it ‘daft Guinness.’” However, Ash’s breakthrough came when he tried using plain air, which worked perfectly. The key, he discovered, was nitrogen. Since air is 78% nitrogen, Ash formulated a draft system with 75% nitrogen, revolutionizing the beer’s texture and creating the creamy consistency that defines Irish stouts today.

Full disclosure: Guinness sponsored the author’s attendance at an International Stout Day festival in 2017, which facilitated interviews with their archivists.