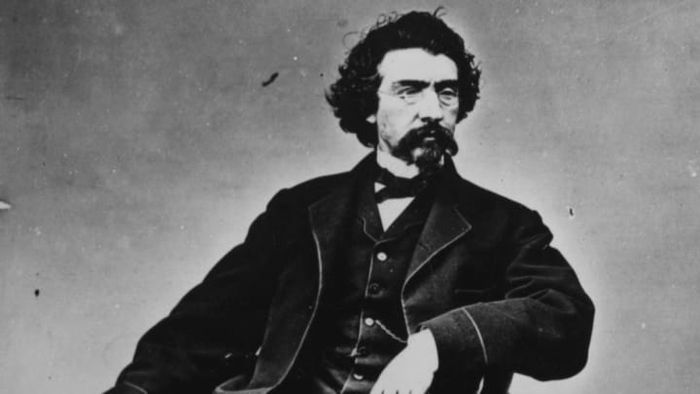

The iconic visuals of the Civil War that come to mind are largely attributed to Mathew Brady and his team. As one of America's pioneering photographers, Brady captured the essence of a divided nation through his lens—a monumental effort that would eventually lead to his decline. Discover some captivating facts about Mathew Brady.

1. HIS EARLY YEARS REMAIN SHROUDED IN INTENTIONAL AMBIGUITY.

Much of Brady's early life remains a mystery. Born around 1822 or 1823 to Irish parents Andrew and Julia Brady, he claimed Ireland as his birthplace on pre-war census records and 1863 draft forms. However, some historians believe he later altered his birthplace to Johnsburg, New York, to avoid anti-Irish prejudice as his fame grew.

Brady had no children, and while it is widely believed he married Julia Handy in 1851, no formal documentation of their marriage exists.

2. HE LEARNED PHOTOGRAPHY FROM THE CREATOR OF MORSE CODE.

At 16 or 17, Brady moved to New York City with artist William Page, who had taught him drawing. However, his artistic aspirations shifted when he became a clerk at A.T. Stewart department store [PDF] and started crafting leather and paper cases for photographers, including Samuel F.B. Morse, the inventor of Morse Code.

Morse, who had mastered the Daguerreotype technique from Louis Daguerre in Paris in 1839, introduced the method to the United States and established a studio in 1840. Brady was among his first students.

3. HE ESTABLISHED A STUDIO IN NEW YORK AND ROSE TO PROMINENCE AS A LEADING PHOTOGRAPHER.

Brady applied the skills he acquired from Morse and launched a daguerreotype portrait studio at Broadway and Fulton Street in New York in 1844, earning the moniker “Brady of Broadway.” His fame soared thanks to his ability to attract notable figures like James Knox Polk and a young Henry James (along with his father, Henry James Sr.) to pose for him. He also had a flair for theatrics: In 1856, he ran an ad in the New York Daily Tribune advising readers to get their portraits taken, cautioning, “You cannot tell how soon it may be too late.”

His growing business compelled him to open a second studio on Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, D.C., in 1849, and later relocate his New York studio to 785 Broadway in 1860.

4. HE GAINED INTERNATIONAL RECOGNITION.

In 1850, Brady released The Gallery of Illustrious Americans, a compilation of lithographs derived from his daguerreotypes of 12 prominent Americans (he had planned 24, but financial constraints prevented it). The publication, along with a feature [PDF] in the first issue of the Photographic Art-Journal in 1851, which hailed Brady as the “fountain-head” of a new artistic wave, elevated his status globally. The profile praised, “We are not aware that any man has devoted himself to [the Daguerreotype art] with such dedication or invested so much time and resources into its advancement. He has earned his prominence through unwavering determination and relentless perseverance.” That same year, at the Crystal Palace Exhibition in London, Brady received one of three gold medals for his daguerreotypes.

5. HE CAPTURED IMAGES OF EVERY PRESIDENT FROM JOHN QUINCY ADAMS TO WILLIAM MCKINLEY ... EXCEPT FOR ONE.

The only president he missed was William Henry Harrison, who passed away just a month after taking office in 1841.

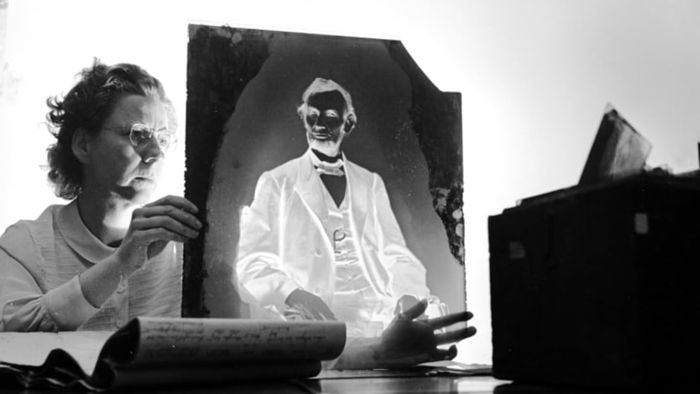

6. HIS PORTRAIT PLAYED A KEY ROLE IN INTRODUCING HONEST ABE TO THE NATION.

During Abraham Lincoln’s 1860 presidential campaign, many viewed him as an awkward rural figure. However, Brady’s dignified portrait of Lincoln, taken after his speech at Cooper Union in New York, helped establish him as a credible candidate in the eyes of the public. (Lincoln reportedly remarked to a friend, “Brady and the Cooper Union speech made me president.”) This marked one of the earliest instances of widespread campaign photography being used to bolster a presidential candidate.

7. HIS STUDIO’S WORK WAS FEATURED ON TWO DIFFERENT DESIGNS OF THE $5 BILL.

Three Lions, Getty Images

Three Lions, Getty ImagesOn February 9, 1864, Lincoln posed for a photo session with Anthony Berger, the head of Brady’s Washington studio. This session produced the two images of Lincoln that would later appear on modern versions of the $5 bill.

The first image, a three-quarter length portrait showing Lincoln seated and facing right, was featured on the bill from 1914 to 2000. When the U.S. currency was updated that year, officials selected another photograph taken by Berger at Brady’s studio, this time depicting Lincoln facing left with his head slightly turned.

As noted by Lincoln historian Lloyd Ostendorf, “Whenever Lincoln posed for portraits, a somber expression would overshadow his features. He adopted what Mrs. Lincoln referred to as his ‘photographer’s face.’ None of the camera studies captured him laughing, as such expressions were impractical given the long exposure times required.”

8. SOME OF HIS MOST FAMOUS WORKS WERE CREATED BY OTHERS.

When the Civil War began in 1861, Brady committed his resources and staff to creating a comprehensive photographic record of the conflict. He sent 20 photographers, including Alexander Gardner and Timothy H. O’Sullivan, to document various war zones. Both Gardner and O’Sullivan eventually left Brady’s employ due to his refusal to credit them individually for their work.

Brady likely captured photographs himself on battlefields such as Bull Run and Gettysburg (though not necessarily during active combat). He later claimed, “I had men stationed across the army, much like a wealthy newspaper.”

9. HE STRUGGLED WITH POOR VISION.

Brady’s eyesight had been problematic since his youth—he was said to be nearly blind as a child and wore thick, blue-tinted glasses as an adult. His increasing reliance on others may have been due to his declining eyesight, which began to worsen in the 1850s.

10. HE PLAYED A PIVOTAL ROLE IN TRANSFORMING COMBAT PHOTOGRAPHY.

Mathew B Brady, Getty Images

Mathew B Brady, Getty ImagesThe team of Brady photographers, who documented the Civil War across the North and South, traveled in horse-drawn wagons known as “Whatizzit Wagons.” These mobile units carried chemicals and portable darkrooms, allowing them to get near battlefields and develop photos swiftly.

Brady’s 1862 New York exhibit, "The Dead of Antietam," showcased unprecedented images of the war’s bloodiest day, shocking the nation. A New York Times reviewer remarked, “Brady has brought the grim reality of war to our doorstep. Though he hasn’t placed bodies in our yards, he has achieved something strikingly similar.”

11. HE USED A GIFT TO PERSUADE GENERALS TO ALLOW HIM TO DOCUMENT THE WAR.

Brady and his team couldn’t simply roam battlefields with cameras—they needed approval. To secure it, Brady arranged a portrait session with Union General Winfield Scott, who posed shirtless as a Roman warrior. During the session, Brady outlined his plan to visually chronicle the war in an unprecedented way. He then gifted Scott some ducks, which finally convinced the general to endorse the project in a letter to General Irvin McDowell. (Sadly, Scott’s Roman warrior portrait has been lost.)

12. HE WAS ACCUSED OF CONTRIBUTING TO UNION BATTLE DEFEATS.

Brady’s initial attempt to document the Civil War took place at the First Battle of Bull Run. Despite approving Brady’s plan, General McDowell was displeased with the photographers’ presence during the conflict.

Brady was reportedly close to the front lines when the battle commenced and soon lost contact with his team. He took refuge in nearby woods, spending the night on a bag of oats. After reuniting with the Army, he returned to Washington, where rumors spread that his equipment had caused a panic, contributing to the Union’s defeat. “Some claim it was the strange, intimidating device that triggered the chaos!” one witness noted. “The fleeing soldiers supposedly mistook it for a steam gun firing 500 bullets a minute and fled in terror!”

13. HE CAPTURED IMAGES OF BOTH SIDES.

Before, during, and after the Civil War, Brady and his team also photographed Confederate figures, including Jefferson Davis, P. G. T. Beauregard, Stonewall Jackson, Albert Pike, James Longstreet, James Henry Hammond, and Robert E. Lee after his surrender at Appomattox Court House. “Many thought it absurd to ask him to pose after his defeat,” Brady later remarked. “But I believed it was the perfect moment for a historical photograph.”

14. HIS CIVIL WAR PHOTOGRAPHY LED TO HIS FINANCIAL DOWNFALL.

Mathew Brady, Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Mathew Brady, Hulton Archive/Getty Images“My wife and even my most cautious friends disapproved of my shift from commercial work to pictorial war coverage,” Brady shared in an 1891 interview. Their concerns proved justified.

Brady poured nearly $100,000 of his personal funds into documenting the Civil War, hoping the government would purchase his photographic archive afterward. However, once the Union emerged victorious, a war-weary public showed little interest in his stark and somber images.

Following the financial crisis of 1873, Brady declared bankruptcy and lost his New York studio. The War Department later acquired over 6000 negatives from his collection—now preserved in the National Archives—for a mere $2840.

Despite creating some of the era’s most iconic photographs, Brady never recovered financially. He passed away alone in New York Presbyterian Hospital in 1896 after being struck by a streetcar.