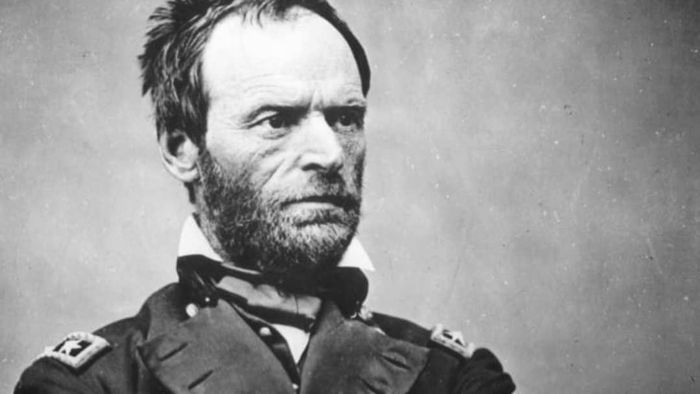

William Tecumseh Sherman presents a paradox—a rugged orphan who despised military formalities yet rose to become one of the most pivotal Union generals in the Civil War. His journey was marked by remarkable triumphs on the battlefield and profound setbacks in his business ventures, leaving his legacy a subject of debate even today. Discover some captivating insights about William Tecumseh Sherman.

1. For much of his early life, William Tecumseh Sherman was known by his middle name.

As detailed in a 1932 biography [PDF] by Lloyd Lewis, Sherman was initially named Tecumseh after the Shawnee chief and went by this name until he was around 9 or 10 years old. Following the death of his father, Charles R. Sherman, an Ohio State Supreme Court justice, in 1829, his mother, Mary Hoyt Sherman, struggled to provide for the family. With the assistance of family friends, Sherman was taken in by Thomas Ewing, who would later become an Ohio Senator. According to Lewis, the Ewings arranged for a priest to visit monthly to educate the children. During one visit, the priest discovered that Sherman had never been baptized. After obtaining consent from Sherman’s mother, the priest inquired about the boy’s name. Upon hearing "Tecumseh," Lewis recounts that the priest declared, “He must be named after a saint,” and since it was the feast day of St. William, the child was baptized William.

In his autobiography, Sherman noted, 'When I was born on February 8, 1820, my father achieved his goal of naming me William Tecumseh.' Modern historians largely rely on this account, confirming he was indeed named William Tecumseh at birth, though he was often referred to by his middle name during his youth, with family affectionately calling him 'Cump.'

2. William Tecumseh Sherman achieved remarkable success at West Point.

At the age of 16, Sherman was appointed to West Point by Senator Ewing in 1836. He graduated sixth in his class and was widely regarded as a standout student. William Rosecrans, a fellow cadet and future Civil War general, recalled Sherman as 'one of the most brilliant and well-liked individuals.'

Sherman's own account of his time at West Point contrasted with his peers' views. In his memoirs, he stated, 'I was never seen as a model soldier, remaining a private throughout my four years. I lacked the neatness and strict adherence to rules that were valued for promotions. Academically, however, I performed well, excelling in subjects like drawing, chemistry, mathematics, and natural philosophy. My annual demerits averaged around 150, which lowered my final class rank from fourth to sixth.'

3. William Tecumseh Sherman wed his foster sister.

Sherman had a deep affection for Ellen, the eldest daughter of the Ewing family, and maintained regular correspondence with her during his time at West Point. Following an extended courtship, the couple tied the knot in 1850, while her father served as the U.S. Secretary of the Interior. At the time of their marriage, Sherman was 30, and Ellen (formally named Eleanor) was 25.

Reflecting on the long-awaited event, Sherman succinctly noted in his memoirs, 'I married Miss Ellen Boyle Ewing, daughter of Thomas Ewing, the Secretary of the Interior. The ceremony was graced by a notable gathering, including figures like Daniel Webster, Henry Clay, T.H. Benton, President [Zachary] Taylor, and his entire cabinet.' Shortly after, the couple relocated to St. Louis, Missouri.

4. Sherman left the military to pursue a career in banking.

After completing his education at West Point, Sherman was deployed to the Second Seminole War, primarily serving in the South. He was later reassigned to California during the Mexican-American War, where he held an administrative position. (Interestingly, he became one of the few senior Civil War officers who did not participate in the Mexican conflict.)

Feeling unprepared for military leadership, Sherman resigned in 1853 and ventured into the private sector. He took on the role of manager at Lucas, Turner & Co., the San Francisco branch of a St. Louis bank. However, economic challenges in California led to the bank's closure by 1857. He attempted to revive his career by managing a New York branch of the same bank, but the Panic of 1857 thwarted his efforts. Subsequently, he briefly practiced law in Kansas before exploring other opportunities. (Years later, while contemplating a position in London, he humorously remarked to his wife, 'I must be the Jonah who caused San Francisco's collapse, and it only took two months in Wall Street to bring down New York. I suspect my arrival in London will mark the end of that great empire.')

5. Sherman played a key role in igniting the California gold rush.

General Photographic Agency/Getty Images

General Photographic Agency/Getty ImagesAlthough his banking career faltered, Sherman significantly contributed to the growth of the California Gold Rush. He persuaded military governor Richard Mason to look into one of the earliest gold discoveries after miners presented half an ounce of placer gold at his office.

Sherman accompanied Mason on an investigative trip to assess the extent of gold deposits in California. Reflecting on the experience, he remarked, 'Rumors of extraordinary finds reached us, spreading like wildfire. The word 'Gold! gold!!' was on everyone’s lips, creating a frenzy. Soldiers began deserting, and civilians organized wagon trains and mule packs to head to the mines. We heard tales of men earning anywhere from fifty to thousands of dollars daily.'

Sherman assisted in drafting a report that Mason sent to Washington, detailing their discoveries and effectively paving the way for a flood of prospectors to California.

6. The outbreak of the Civil War motivated William Tecumseh Sherman to rejoin the military.

In January 1860, Sherman became the headmaster of a military academy in Louisiana, a position secured through recommendations from friends Braxton Bragg and P.G.T. Beauregard (both of whom later served as Confederate officers). He remained in this role for a year but resigned and moved back to St. Louis after Louisiana seceded. Sherman was a staunch Union supporter, yet he believed the growing North-South conflict was avoidable and viewed Lincoln’s efforts to address secession as inadequate.

Following the attack on Fort Sumter in April 1861, which marked the beginning of the Civil War, Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to suppress the rebellion. Initially skeptical, Sherman remarked, 'Trying to stop this with such measures is like using a squirt-gun to extinguish a house fire.' Nevertheless, he asked his brother, Ohio Senator John Sherman, to secure him a colonel’s commission in the Army.

7. Following the Union’s loss at Bull Run, Sherman nearly resigned once more.

Sherman participated in the Union’s crushing defeat at the First Battle of Bull Run in July 1861. A month later, he met with Lincoln and expressed his 'strong preference for serving in a lower-ranking role, refusing any higher command.' Despite his request, Sherman was appointed as second-in-command of the Army of the Cumberland in Kentucky, where his deepening depression nearly led him to leave the military again.

Sherman worried that his troops were insufficient to confront the Confederates, and with units dispatched to secure multiple regions, his army grew even weaker. 'Do not assume,' he wrote, 'that I am overstating the situation. The facts are as I’ve described, and the outlook is grim. A more optimistic leader might fare better here, as I must act according to my own judgment.'

Reporters observing his actions noted that 'rumors quickly spread about his mental state, suggesting he was deeply troubled and overwhelmed.' A December 11, 1861, headline in the Cincinnati Commercial [PDF] declared, 'General William T. Sherman Insane,' while another paper stated, 'General Sherman, recently in command in Kentucky, is reportedly insane. It’s almost a kindness to believe so.'

On November 8, he was removed from command and granted a three-week leave to return home to Lancaster, Ohio, where Ellen assisted in treating 'the melancholic tendencies that run in your family.'

8. Sherman shared a close friendship with Ulysses S. Grant.

After recovering his morale, Sherman was stationed in Cairo, Illinois, as the logistics coordinator for Ulysses S. Grant, who would become both a trusted ally and close friend. Their bond and military skills were put to the test at the Battle of Shiloh, where Sherman, serving under Grant, led a crucial counterattack against Confederate forces after they ambushed Union troops on the morning of April 6, 1862.

After repelling Confederate assaults, the two generals reunited late that night. Historian Bruce Catton described the scene: 'Sherman found Grant standing under a tree in the pouring rain, his hat pulled low and coat collar turned up, holding a faintly glowing lantern with a cigar clenched between his teeth. Sherman, moved by what he later called a 'wise and sudden instinct,' avoided mentioning retreat and instead remarked, 'Well, Grant, we've had a hell of a day, haven’t we?' Grant simply replied, 'Yes,' puffing his cigar in the dark, before adding, 'But we’ll beat them tomorrow.'

9. William Tecumseh Sherman revolutionized warfare.

iStock

iStockSherman’s military legacy is largely defined by his March to the Sea, a month-long campaign during which he led 60,000 troops to devastate Georgia’s industry, infrastructure, and civilian properties behind Confederate lines, aiming to cripple their economy. 'The complete destruction of Georgia’s roads, homes, and population,' he wrote, 'will undermine their military capabilities... I will march through and make Georgia howl!' This strategy, known as 'hard war,' was later used in his campaigns against Native American tribes post-Civil War. Sherman assured his superiors, 'I am penetrating the Confederacy’s heartland, leaving a mark that will be remembered for decades.'

10. William Tecumseh Sherman did not support abolition.

Sherman held prejudiced views: In 1860, he stated, 'No amount of legislation can alter the nature of the negro; he must either remain subordinate to the white man, integrate, or face destruction. Harmony between the two races is impossible without a master-slave dynamic.'

Despite fighting for the Union, Sherman refused to enlist black soldiers in his forces. 'I would rather this remain a white man’s war,' he remarked. 'Given my views and experiences with negroes, and my inherent prejudice, I cannot yet trust them with weapons in critical situations.'

According to the National Archives, 'By the Civil War’s conclusion, approximately 179,000 black men (10 percent of the Union Army) had served as soldiers, with an additional 19,000 in the Navy. Despite facing discrimination, black units demonstrated exceptional valor in battles such as Milliken's Bend and Port Hudson in Louisiana, Nashville in Tennessee, and Petersburg in Virginia. Sixteen black soldiers were honored with the Medal of Honor.'

11. Sherman’s lenient surrender terms caused significant controversy.

Shortly after Lincoln’s assassination in April 1865, Sherman met Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston in Durham, North Carolina, to negotiate the surrender of remaining Confederate forces in the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida. Unaware of the specific terms agreed upon elsewhere, Sherman drafted his own conditions, offering Confederates citizenship and property rights if they disarmed and returned home peacefully.

News of the terms sparked immediate outrage in Washington. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton criticized Sherman’s leniency, claiming it 'undermined all the progress we achieved during the war... giving Jeff Davis a chance to flee with his wealth.' Rhode Island Senator William Sprague IV even demanded Sherman’s removal from command.

Johnston ultimately accepted a straightforward military surrender without any civil assurances. Over time, Sherman and Johnston developed a strong friendship, with Johnston even serving as a pallbearer at Sherman’s funeral in 1891.

12. William Tecumseh Sherman is credited with a famous wartime expression.

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesSherman’s candid reflection on the Civil War was captured in a speech he delivered to the Michigan Military Academy’s graduating class on June 19, 1879. While published accounts vary, he reportedly declared to the cadets, 'War is Hell!'

Some versions of the speech quote Sherman as saying, 'You cannot fathom the horrors of war. Having endured two wars, I’ve witnessed cities and homes reduced to ashes. I’ve seen countless men lifeless on the ground, their faces turned toward the heavens. Believe me, war is Hell!'

Others recall Sherman stating, 'Many of you young men view war as glorious, but let me tell you, it is nothing but Hell,' or 'Some of you believe war is full of glamour and honor, but boys, it is pure Hell.'

13. Sherman had a lifelong passion for theater.

During a strategic planning stop in Nashville with Grant, Sherman and several generals attended a local production of Shakespeare’s Hamlet. However, their stay was brief.

Sherman reportedly found the actors’ performances so poor that he couldn’t continue watching and openly expressed his disappointment to the audience. He and Grant left to dine at an oyster restaurant, but their meal was interrupted by the Union’s military curfew.

14. Sherman had no interest in becoming president.

Following the war, Sherman was frequently suggested as a Republican presidential candidate. During the 1884 Republican National Convention, when he was seriously considered, he firmly declined, stating, 'If nominated, I will not accept; if elected, I will not serve.' He passed away in 1891 due to pneumonia.