Meriwether Lewis and William Clark are recognized for documenting over 178 plants and 122 animal species during their historic expedition across the North American plains in the early 1800s. While they weren't the first to observe these creatures, they were instrumental in introducing them to Western scientific knowledge. Below are 15 of the animals they detailed in their explorations.

Pronghorn Antelope

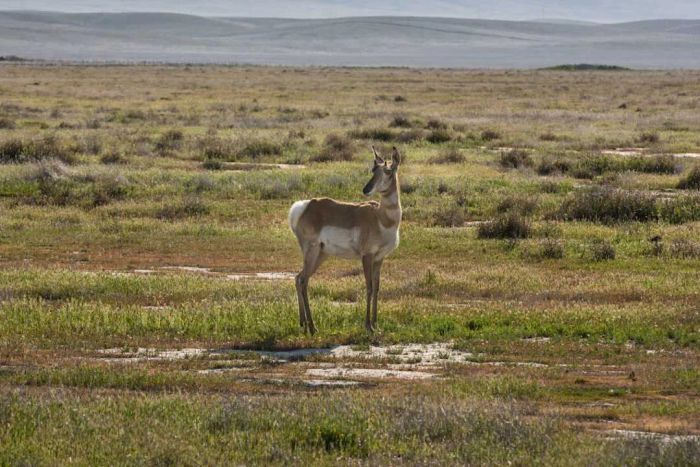

A pronghorn at Carrizo Plain National Monument. | George Rose/GettyImages

A pronghorn at Carrizo Plain National Monument. | George Rose/GettyImagesLewis and Clark documented numerous animals during their journey, including pronghorns—often referred to as pronghorn antelopes, despite not being true antelopes. They are unique as the sole members of the Antilocapridae family. Spanish explorers in the 16th century had likely mentioned these creatures, and Native American tribes had been hunting pronghorns for sustenance long before their arrival.

Grizzly Bear

In 1804, Lewis and Clark first encountered signs of the formidable grizzly bear in South Dakota, near the Moreau River, where they discovered paw prints in the mud. Throughout their expedition, they encountered and hunted several of these massive bears. The Blackfeet Nation, who had coexisted with the grizzly bear for generations, referred to them as “kyaio.” By the early 20th century, hunting and habitat loss had nearly eradicated grizzly bears from the Midwest.

Swift Fox

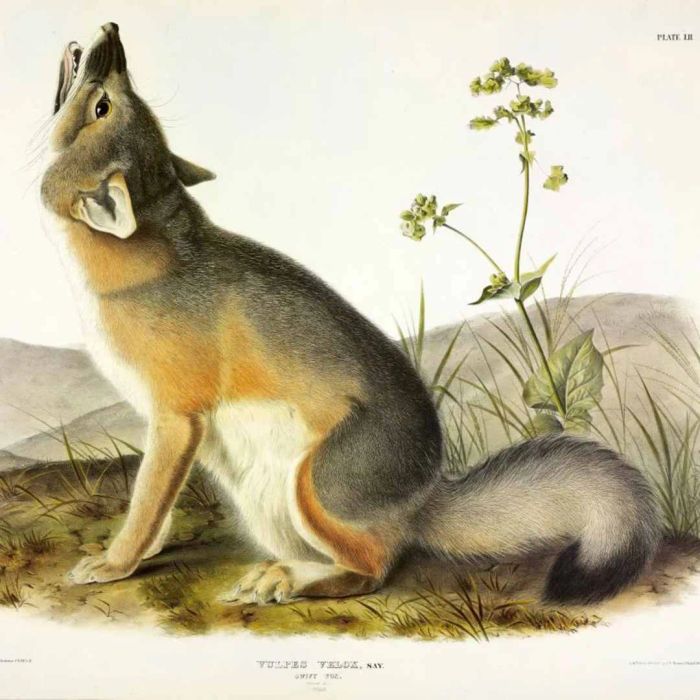

A swift fox depicted by John J. Audubon. | Heritage Images/GettyImages

A swift fox depicted by John J. Audubon. | Heritage Images/GettyImagesWhen Lewis and Clark first encountered the swift fox, they were puzzled. Lewis noted that the small, speedy animal was unfamiliar to him. Like many other species, swift foxes experienced a significant decline in numbers as European settlers expanded westward. In 2020, some tribes initiated a five-year program to reintroduce these animals and help rebuild their populations.

Black-Tailed Prairie Dog

A delightful little creature, indeed. | Marcos del Mazo/GettyImages

A delightful little creature, indeed. | Marcos del Mazo/GettyImagesLewis and Clark not only documented the prairie dog but also captured a live one to present to President Thomas Jefferson. Clark referred to the animal as a “charming little critter.” Indigenous peoples, however, had long been familiar with prairie dogs, known as “pìspíza” in the Lakota language, well before the expedition.

White-Tailed Jack Rabbit

Lewis observed that the white-tailed jack rabbit was “remarkably swift.” He noted its similarities to the European hare and even labeled it the “giant Hare of America.”

Bushy-Tailed Woodrat

Lewis noted that the bushy-tailed woodrat was “previously unknown to science” and resembled an ordinary rat with oversized ears. These rodents, often referred to as packrats, are known for gathering a variety of random objects at their nests.

Mule Deer

A herd of mule deer in Montana. | William Campbell/GettyImages

A herd of mule deer in Montana. | William Campbell/GettyImagesLewis and Clark first spotted mule deer in Nebraska. Over the following eight months, Lewis observed so many that he provided an in-depth account of the species, highlighting their black tails and preference for rugged, mountainous terrain. These deer are widely found in the western regions and have historically been a vital resource for Indigenous communities, providing both food and hides.

Long-Billed Curlew

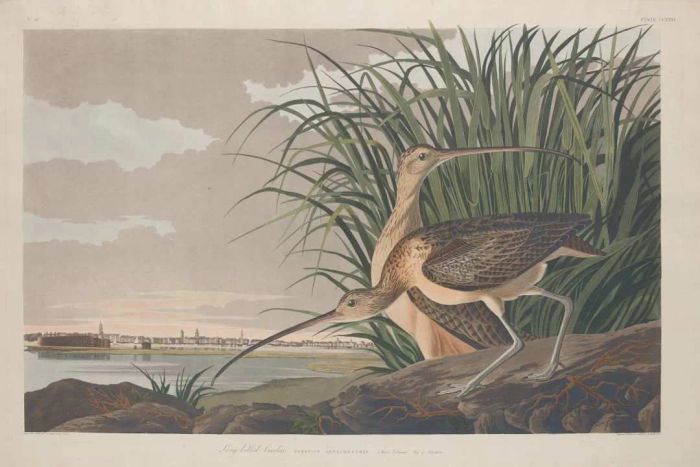

Long-Billed Curlew depicted by Robert Havell. | Heritage Images/GettyImages

Long-Billed Curlew depicted by Robert Havell. | Heritage Images/GettyImagesLewis and Clark first observed the long-billed curlew close to Great Falls, Montana. This shorebird, distinguished by its lengthy bill and legs, migrates to the Great Basin and Great Plains during the summer breeding period. The explorers remarked that it stood out from the other birds they had encountered.

Bison

Since 2016, bison have held the title of the United States' national mammal. | George Frey/GettyImages

Since 2016, bison have held the title of the United States' national mammal. | George Frey/GettyImagesLewis and Clark first observed bison tracks in Missouri. Within a month, they encountered the animals—mistakenly referring to them as “buffalo.” They later hunted, preserved, and consumed these massive creatures. Bison have long been a vital resource for many Indigenous tribes in North America, each with their own name for the animal. The Blackfoot Nation calls it iinniiwa, the Lakota people use tatanka, the Navajo Nation refers to it as “ivanbito,” and the Paiute know it as kuts.

Elk

An elk resting on a mountaintop in Rocky Mountain National Park. | John Greim/GettyImages

An elk resting on a mountaintop in Rocky Mountain National Park. | John Greim/GettyImagesThroughout their journey, Lewis and Clark encountered numerous elk—they hunted 94 of them in just the first year. The explorers utilized these animals for sustenance and crafted ropes and moccasins from their hides and fur.

Mountain Beaver

In 1806, Lewis described a creature roughly the size of a squirrel with soft fur. He noted that the Chinook and Clatsop tribes referred to it as sewelel. Although it was later named “Mountain Beaver,” it is neither a beaver nor exclusive to mountainous regions. Instead, it resembles prairie dogs in behavior and lives in underground burrows.

Richardson’s Ground Squirrel

In 1805, Lewis described a rodent brought to him by his men, which was larger and more “attractive” than the squirrels he had seen before. He observed its flat tail, reddish-brown fur, and its burrowing behavior.

Long-Tailed Weasel

Clark first mentioned the long-tailed weasel in November 1804. Their fur, which turned white in winter and brown in summer, was highly valued and traded between Native American tribes and Western settlers.

Sea Otter

Admire that luxurious fur. | Mario Tama/GettyImages

Admire that luxurious fur. | Mario Tama/GettyImagesSea otters were first mentioned in Lewis and Clark’s journals in February 1806. Lewis noted that these coastal creatures were roughly the size of a mastiff dog—spelled as “mastive” by him. He also praised their fur as “the most exquisite in the world,” clearly referring to its texture and appearance rather than its taste.

Coyote

Not a wolf. | Anadolu/GettyImages

Not a wolf. | Anadolu/GettyImagesLewis and Clark first observed what they called a “prairie wolf” in August 1804. They frequently encountered these animals during their journey, describing their distinctive barks, bushy tails, and compact, fox-like stature. However, these so-called “prairie wolves” were not true wolves but coyotes, a term derived from the Nahuatl word coyotl.