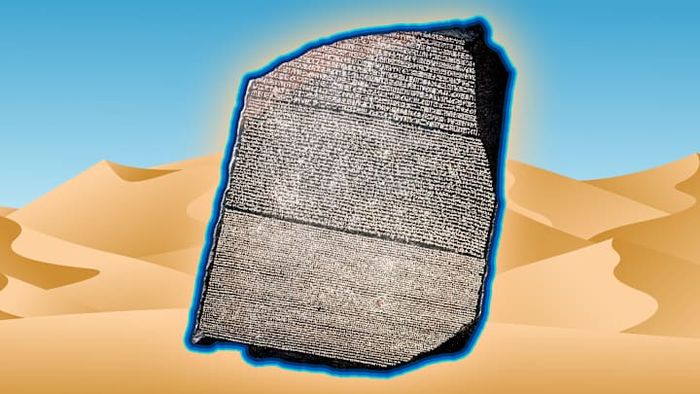

Discovered on July 15, 1799, by French troops during their Egyptian campaign, the Rosetta Stone was an extraordinary stroke of luck. Featuring three distinct scripts, it became the crucial tool for unlocking the mysteries of hieroglyphs, the ancient Egyptian writing system that had baffled experts for ages. While its significance in translation is widely celebrated, the dramatic and often overlooked story of its unearthing and decoding adds another layer of intrigue.

The text on the Rosetta Stone is a royal proclamation praising a young monarch.

The Rosetta Stone is a fragment of a larger slab, or stele, likely displayed in a temple close to el-Rashid (Rosetta), where it was found. It fractured long ago. Dating back to 196 BCE, it serves as a piece of ancient propaganda—officially called the Memphis Decree—celebrating the rule and virtues of Ptolemy V, who ascended the throne at just 5 years old following the assassination of his parents and was crowned at 12. Given his youth and the empire's instability, Ptolemy likely sought support from the priesthood. The inscription praises him, stating, '[He] has generously funded the temples with money and grain, investing heavily to restore Egypt's prosperity.'

The stone features inscriptions in three separate scripts.

Although incomplete, the Rosetta Stone critically retains the three languages from the original stele: hieroglyphs, the empire's sacred script; Egyptian demotic, the everyday language; and Greek, the official tongue during Macedonian rule in Egypt. All three versions deliver the same royal decree, with minor differences, suggesting the message was widely disseminated. For the French discoverers, this made it a vital translation tool, especially the Greek section, which enabled scholars to decode hieroglyphs after they fell out of use in the 4th century under Roman rule, deemed a pagan practice.

It has a weight of 1676 pounds.

Visitors at the museum observe the Rosetta Stone displayed behind glass. | Fox Photos/GettyImages

Visitors at the museum observe the Rosetta Stone displayed behind glass. | Fox Photos/GettyImagesThe Rosetta Stone is an imposing artifact. Crafted from granodiorite, a granite variant rich in quartz and feldspar crystals, it measures up to 112.3 centimeters (44.2 inches) in length, 75.7 centimeters (29.8 inches) in width, and 28.4 centimeters (11.2 inches) in thickness. Its weight approaches three-quarters of a ton.

For centuries, the Rosetta Stone was embedded within the walls of a fortress.

In the 4th century, Roman Emperor Theodosius I ordered the destruction of many Egyptian temples, and their remnants were later used as quarries by occupying forces. Before its rediscovery by the French army in the late 18th century, the invaluable Rosetta Stone was integrated into the structure of an Ottoman fortress wall.

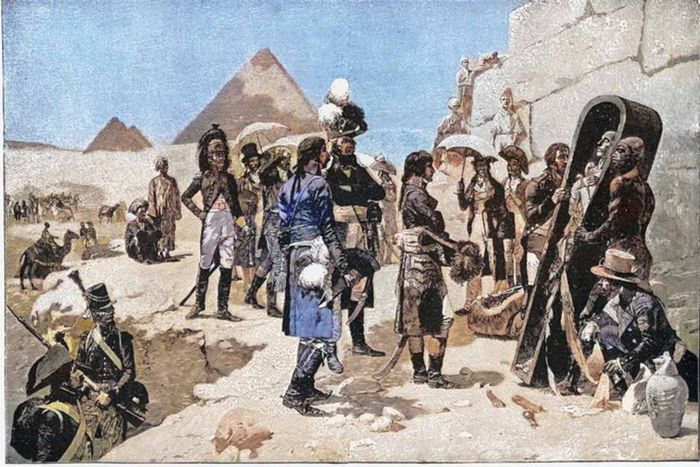

Napoleon spearheaded a scientific expedition to document Egyptian monuments.

Amid the French Revolutionary Wars, France and Britain were adversaries, and French troops invaded Egypt to disrupt British trade routes to India and forge economic alliances in the Middle East. Napoleon Bonaparte, then a general leading the Egyptian Campaign, was an intellectual who aimed to meticulously record Egypt's cultural legacy (and transport much of it to France). Accompanied by a team of naturalists, engineers, historians, political scientists, and art experts, Napoleon founded the Institut d’Égypte in 1798 to oversee these efforts. He directed his officers and soldiers to actively search for significant artifacts.

An engineer quickly recognized the immense importance of the Rosetta Stone.

A whimsical depiction of Napoleon receiving a mummy during his Egyptian Campaign. | mikroman6/Moment/Getty Images

A whimsical depiction of Napoleon receiving a mummy during his Egyptian Campaign. | mikroman6/Moment/Getty ImagesWhile renovating sections of the Ottoman fort, renamed Fort Julien by the army, engineer Pierre-François Bouchard spotted a granite slab protruding from the ground. Upon closer examination, he noticed it featured multiple lines of script and promptly reported it to General Jacques-François Menou, a senior general in Egypt who was present at the location. Soldiers unearthed the stone and later presented it to Napoleon.

Then the British took possession of it.

Following their victory over Napoleon’s forces at the Siege of Alexandria in 1801, British troops confiscated numerous Egyptian artifacts collected by the Institut d’Égypte over the preceding years, including the Rosetta Stone. General Menou attempted, without success, to declare the stone as his personal property. Instead, British authorities demanded the Rosetta Stone as part of France’s formal surrender terms, in exchange for permitting Menou’s troops to leave the city.

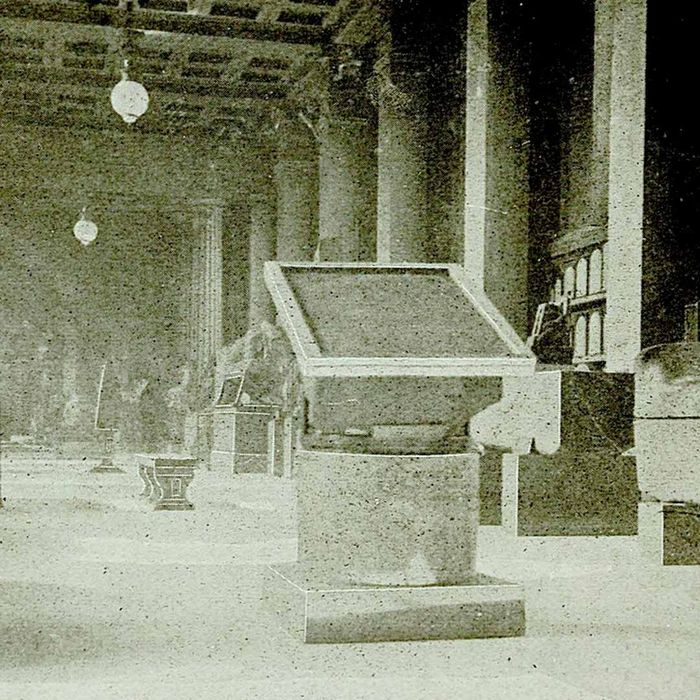

The Rosetta Stone has resided in the British Museum since 1802.

Once the stone was secured, British authorities transported it to the British Museum in London, which had opened in 1757 as the world’s first national public museum. Initially housed in a 17th-century mansion known as Montagu House, the Rosetta Stone and other heavy artifacts soon overwhelmed the building’s structure, prompting their relocation to the museum’s current site on Great Russell Street in Bloomsbury.

In the past, visitors were permitted to touch it.

Today, the Rosetta Stone is exhibited in a glass case. | SOPA Images/GettyImages

Today, the Rosetta Stone is exhibited in a glass case. | SOPA Images/GettyImagesFor many years, the Rosetta Stone remained exposed in the museum. Despite being advised against it, visitors frequently approached and touched the stone, often running their fingers over the inscriptions—a practice that would undoubtedly alarm today's museum curators. Recognizing the potential harm to the artifact's preservation, the museum eventually decided to encase it in glass.

Decoding the text on the Rosetta Stone required over twenty years of scholarly effort.

The Greek and demotic scripts on the stone, comprising 54 and 32 lines respectively, were translated relatively swiftly by scholars. However, the 14 lines of hieroglyphs posed a greater challenge, taking years to fully decode. This difficulty was partly due to the misconception that hieroglyphs were purely symbolic, rather than primarily phonetic. Additionally, the competitive tension between British and French scholars, stemming from their nations' historical disputes over the stone, fueled an intense rivalry in the decipherment race. Thomas Young, a British scholar, achieved a significant advancement by identifying the importance of cartouches—encircled proper names—and sharing his insights in 1814.

Upon uncovering a pivotal insight, Champollion collapsed from the excitement.

Building on Young's discoveries, French Egyptologist Jean-François Champollion continued the arduous task of decoding the hieroglyphs. His perseverance paid off when he realized that a symbol representing the sun matched the Egyptian term 'ra', meaning 'sun', which was part of the name 'Ramses', a pharaoh linked to the sun deity Amun-Ra. This revelation confirmed the phonetic nature of hieroglyphs. Overwhelmed by his breakthrough, Champollion rushed to the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, where his brother was employed. He reportedly exclaimed, 'I have it!' upon entering his brother's office, before fainting from the sheer excitement.

Champollion persisted in solving the enigma and achieved a complete translation by 1822. This breakthrough led to a deeper comprehension of ancient Egypt's language and culture.

For two years, the Rosetta Stone was housed in a tube station.

The Rosetta Stone, encased in glass and showcased at the British Museum during the early 1900s, is documented in this image from Wikimedia Commons, available in the Public Domain.

The Rosetta Stone, encased in glass and showcased at the British Museum during the early 1900s, is documented in this image from Wikimedia Commons, available in the Public Domain.Amid World War I, concerns over air raids led British Museum authorities to relocate the Rosetta Stone and other chosen artifacts to a Postal Tube Railway station in Holborn, located 50 feet below ground.

France regained possession of the artifact—albeit only for a month.

Following its discovery and subsequent loss, France was granted the opportunity to exhibit the artifact in 1972. This event marked the 150th anniversary of Champollion’s publication, “Lettre à M. Dacier,” which detailed his translation of the Rosetta Stone’s hieroglyphs. The stone attracted visitors from across the globe to the Louvre, sparking rumors that France might retain it. However, it was sent back to the British Museum after just one month.

No single, definitive English translation of the Rosetta Stone’s inscriptions exists.

The Rosetta Stone’s three sections vary slightly, and translation is inherently subjective, making it impossible to produce a single, authoritative version of the royal decree. The English translation of the demotic section {PDF} is not particularly engaging to read.

Egypt has expressed a desire to reclaim the artifact.

In 2003, Egypt formally demanded the repatriation of the Rosetta Stone, emphasizing its significance as a vital element of the nation’s cultural heritage. Over the years, both officials and the public, notably renowned archaeologist and former Egyptian Minister of Antiquities Zahi Hawass, have persistently urged the British Museum to return the artifact. Despite repeated appeals, the museum has refused, though it did provide Egypt with a life-sized fiberglass replica of the stone in 2005.