Looking at Franz Marc's Yellow Cow, you’re drawn into a vibrant, almost otherworldly painting filled with energy. Yet beneath its bold strokes and avant-garde design lies the poignant and intricate story of a deep connection between two artists, and the journey that ultimately brought them together.

1. YELLOW COW MARKS A DISTINCT DEPARTURE FROM MARC'S EARLIER WORKS.

Franz Marc, initially a philosophy student, pursued painting at the Munich Academy of Art in the early 20th century. His early education was grounded in natural realism, aiming to depict his subjects with true-to-life proportions, expressions, and hues. In 1902, he painted Portrait of the Artist's Mother, immortalizing his mother Sophie Marc, a devout Calvinist and homemaker. In this profile portrait, she sits absorbed in a book, illuminated by an unseen lantern. Although Marc would later embrace bold color palettes, this piece is dominated by darker tones, creating a somber, almost flat visual effect.

2. YELLOW COW WAS INSPIRED BY GERMAN NUDISTS.

In the early 20th century, Germany experienced a resurgence of the back-to-nature movement, leading to the rise of artist collectives and nudist colonies. This celebration of nature and its raw beauty deeply resonated with Marc, who later explained, "People with their lack of piety, especially men, never touched my true feelings. But animals with their virginal sense of life awakened all that was good in me."

3. MARC SAW ANIMALS AS DIVINE BEINGS.

Inspired by the naturalists, Marc grew to appreciate the rural beauty of the countryside. He left behind the fast-paced, intellectual atmosphere of Munich, seeking the tranquility and spiritual depth he believed could be found in the simplicity of animal life. He came to regard animals as having a "god-like presence and power." In a 1908 letter, Marc elaborated on this belief, writing, "I am trying to intensify my ability to sense the organic rhythm that beats in all things, to develop a pantheistic sympathy for the trembling flow of blood in nature, in trees, in animals, in air—I am trying to make a picture of it … with colors which make a mockery of the old kind of studio picture."

4. ANIMALS BECAME A CENTRAL THEME IN MARC'S WORK.

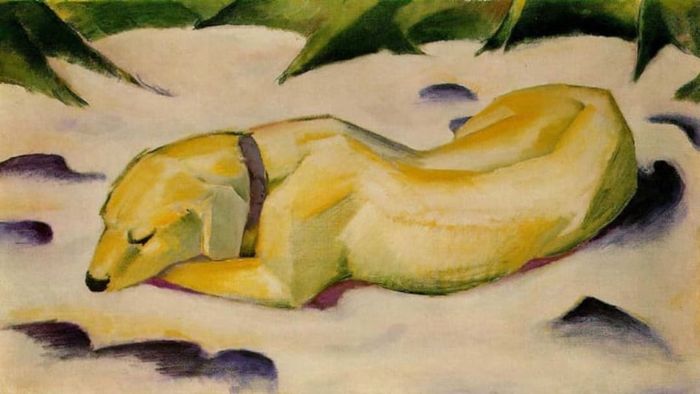

Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainBy 1907, Marc was concentrating on expressing the spiritual essence he saw in animals. Other key works in this direction include The Fox, Dog Lying In The Snow, The Little Blue Horses, The Red Bull, Little Monkey, Monkey Frieze, Wild Boars in the Water, and The Tiger.

5. YELLOW COW IS A REMARKABLY LARGE PAINTING.

At 55 3/8 by 74 1/2 inches, it spans nearly 5 feet by 6 feet in size.

6. MARC CREATED HIS OWN SYSTEM OF COLOR SYMBOLISM.

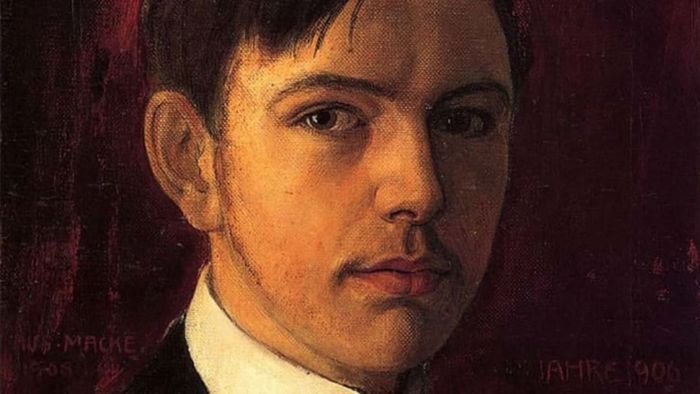

Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainIn Marc's work, colors became symbols of various emotions and themes. In 1910, he shared his thoughts on color in a letter to his friend and fellow artist, August Macke. Marc wrote, "Blue represents the male principle, sharp and spiritual. Yellow embodies the female principle, soft, joyful, and spiritual. Red, on the other hand, signifies matter, harsh and weighty, always needing to be subdued or overcome by the other two."

7. YELLOW COW COULD BE AN UNORTHODOX WEDDING PORTRAIT.

Delving into Marc's works and his reflections on color, art historian Mark Rosenthal suggested that the playful cow may subtly depict Marc's second wife, Maria Franck, with the distant blue mountains symbolizing the artist himself. Painted in the same year the couple married, it might be interpreted as a nod to their union. The merging of blue in the cow's spots could represent the fusion of masculine and feminine.

8. MARIA FRANCK WAS A PERSISTENT INSPIRATION FOR HER HUSBAND.

In 1906, before marrying her, Marc created a more conventional portrait of his future wife, titled Mädchenkopf, which translates—somewhat unromantically—to "girl's head." That same year, he also painted Franck in the abstract work Two Women on the Hillside. Later, he painted Maria Franck in a White Cap.

9. MARC AND FRANCK SHARED A COMPLEX ROMANCE.

An artist herself, Franck met Marc at a costume ball in Schwabing, Germany. They quickly bonded, along with illustrator Marie Schnür, leading to a creative summer in Bavaria filled with rumors of three-way affairs. Schnür was the other woman who posed for Two Women on the Hillside and appeared in an infamous NSFW photograph from their sun-soaked season. Marc would marry both women, starting with Schnür.

Their first marriage was one of convenience, meant to help Schnür gain custody of her illegitimate son. This marriage was brief, lasting from 1907 to 1908, and little is known beyond that. However, when Schnür accused Marc of infidelity, he was forbidden from marrying again until he received a special dispensation, which took years. Although Marc and Franck had planned to wed in 1911, they didn’t marry until June 3, 1913, in Munich.

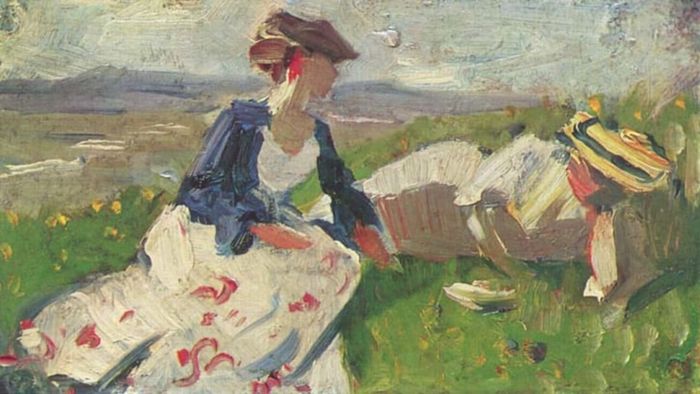

10. TWO WOMEN ON THE HILLSIDE MARKED A TURNING POINT IN MARC'S ARTISTIC STYLE.

Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainLooking back at 1906's Two Women on the Hillside, it appears to foreshadow Yellow Cow. The painting of the two women who would inspire Yellow Cow marks Marc's departure from the German realist style he had studied in college. Instead, the looser brushwork reflects a Post-Impressionist influence, while the abstract nature of the subjects hints at the emerging German Expressionism movement that he would eventually join. Additionally, the repetition of lines—from the curve of the woman's hip to the hill beyond—echoes in Yellow Cow, where the cow's haunches mirror the undulating mountains behind her.

11. YELLOW COW WAS PART OF THE DER BLAUE REITER ART MOVEMENT.

Named after a Wassily Kandinsky painting, this movement included members like Kandinsky, Marc, Macke, Alexej von Jawlensky, Marianne von Werefkin, and Gabriele Münter. The Der Blaue Reiter (translated as The Blue Rider) didn't have a formal manifesto, but its members were united by a shared desire to convey spiritualism through their art, often focusing on the use of color. Rejected by mainstream exhibitions, they organized their own shows and published an almanac that championed contemporary, primitive, and folk art, as well as children's paintings.

12. THE DER BLAUE REITER MOVEMENT WAS SHATTERED BY WORLD WAR I.

The Blue Rider movement lasted only from 1911 to 1914, largely due to escalating tensions between nations that forced Russian artists to return to their homeland, while German artists, including Marc and Macke, were drafted into military service. As these artists scattered, the movement faded. However, it played a crucial role in the development of Expressionism, and its works continue to resonate.

13. MARC DID NOT LIVE TO WITNESS THE IMMORTALIZATION OF HIS LEGACY.

Marc's animal-themed paintings would go on to captivate audiences for years, becoming prized possessions for collectors and art museums. A plaque would later be installed at his birthplace in Munich, honoring him as a founder of Der Blaue Reiter. Tragically, Marc was killed on March 4, 1916, during the Battle of Verdun, at the age of 36.

14. MARIA FRANCK ENSURED HIS ART WOULD BE PRESERVED.

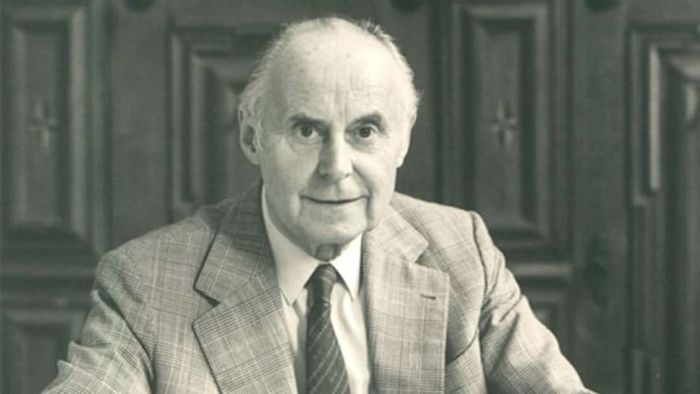

Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainMarc's widow entrusted the records of his life and writings to German art historian Klaus Lankheit. She reached out to German writer and gallery owner Herwarth Walden to organize a posthumous exhibition of her late husband's works in October of 1916. While continuing to create and showcase her own art, she also collected Marc's letters from the warfront, which were later published in 1920 in a two-volume book titled Briefe, Aufzeichnungen und Aphorismen (translated as Letters, Records, and Aphorisms). According to the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, where copies are preserved, "The first volume includes letters written between September 1914 and March 1916, as well as records accompanied by color plates, while the second volume presents the artist’s sketchbook." Franck ensured Marc's legacy lived on, offering the world a window into his life and thoughts.

15. YELLOW COW IS CHERISHED AS A VIBRANT MASTERPIECE.

Though comparing your wife to a cow may seem odd, the prevailing view of Yellow Cow is that it symbolizes the joy and happiness Marc found in his relationship with Franck. The cow's radiant colors are exuberant, yet they harmonize with the hues of the surrounding landscape. She fits into her environment perfectly. Her stance is lively and confident, almost as though she's dancing. If you look closely, you can even spot a faint smile on her face. It’s an unconventional love letter, one that has outlasted its creators and now hangs at the Guggenheim in New York City, where it continues to inspire generations.