Since its creation in 1499, Michelangelo's Pietà has stirred deep emotions, faith, and artistic emulation through its delicate portrayal of the Virgin Mary and the body of Christ. However, there are still many secrets about this centuries-old sculpture that continue to emerge.

1. A French cardinal commissioned Michelangelo’s 'Pietà' for his tomb.

French cardinal Jean de Billheres, who had served the church in Rome, sought to leave a lasting legacy after his death. To fulfill this ambition, he commissioned Michelangelo to create a memorial for his tomb, depicting a scene commonly found in Northern European art: the heart-wrenching moment when the Virgin Mary cradles the body of Christ after his crucifixion.

In fact, de Billheres’s request was far more ambitious. Michelangelo’s brief was to craft “the most beautiful marble work in Rome, one that no other living artist could surpass.” While this may have intimidated other sculptors, Michelangelo approached the challenge with full confidence. Today, many consider the Pietà his finest achievement, even surpassing works like the David and the Sistine Chapel ceiling.

2. Over two centuries later, the Pietà was relocated to St. Peter’s Basilica.

St. Peter's Basilica. | Elisabetta A. Villa/GettyImages

St. Peter's Basilica. | Elisabetta A. Villa/GettyImagesThis grand Renaissance church houses the iconic sculpture in the first chapel on the right as you enter. Since its installation, it has captivated countless visitors to Vatican City. For those unable to visit in person, a virtual tour is available here.

3. Michelangelo sculpted the Pietà from a single block of marble.

He specifically chose Carrara marble, a white and blue stone from the Italian region renowned for its marble quarries. This material has been a preferred choice for sculptors since the days of Ancient Rome.

4. Pietà is the only sculpture Michelangelo ever signed.

If you look closely, you can spot the sculptor’s signature across Mary’s chest. The famous sixteenth-century art historian Giorgi Vasari recounted the story of how Michelangelo left his mark:

“One day Michelagnolo [sic], entering the place where it was set up, found there a great number of strangers from Lombardy, who were praising it highly, and one of them asked another who had created it. The reply was, 'Our Gobbo from Milan.' Michelagnolo remained silent but found it strange that his work should be credited to someone else. That night, he locked himself in, brought a light and his chisels, and carved his name into it.”

Michelangelo later regretted the vanity of this act and vowed never to sign another of his creations.

5. The sculpture catapulted Michelangelo to fame at the age of just 24.

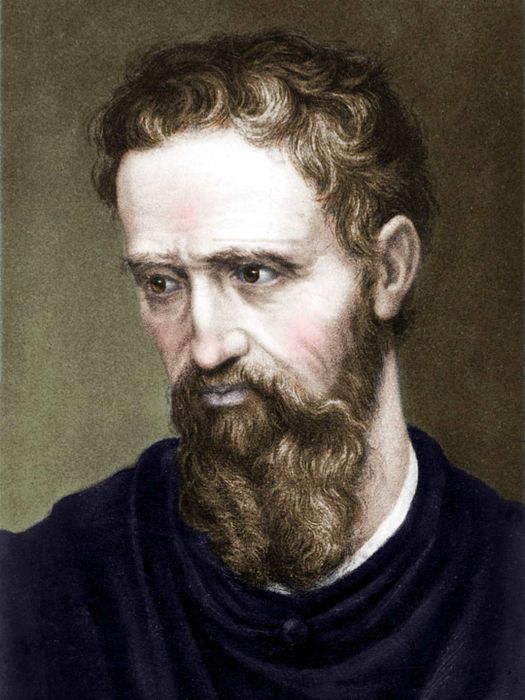

Michelangelo. | Culture Club/GettyImages

Michelangelo. | Culture Club/GettyImagesBy prominently displaying his name on the Pietà, Michelangelo’s reputation grew alongside the public’s admiration for the statue. The artist lived to 88, enjoying decades of recognition and reverence for his masterpieces.

6. The sculpture has faced criticism for Michelangelo's portrayal of Mary.

Some church critics argued that the artist made her appear too youthful to be the mother of a 33-year-old Jesus, the age believed for his death. Michelangelo defended his choice to his biographer Ascanio Condivi, saying: “Do you not know that chaste women remain more youthful than those who are not? How much more so in the case of the Virgin, who had never experienced even the slightest impure desire that could alter her body?”

7. The Pietà blends various sculpting styles.

Michelangelo is celebrated for merging Renaissance ideals of classical beauty with more naturalistic poses. Another reflection of Renaissance influence can be seen in the structure of the sculpture, which takes on a pyramid-like shape formed by Mary's head, flowing down through her arms to the hem of her robes.

8. Mary’s robes conceal a creative solution.

If you look closely, you'll notice that Mary's head appears slightly too small in proportion to her large body. To make her cradle her adult son as Michelangelo envisioned, he had to sacrifice realistic proportions. He opted to make Mary—who is the statue's support—oversized. To minimize the obviousness of this artistic choice, Michelangelo carved delicate folds of fabric around her, effectively camouflaging her exaggerated form.

9. The Pietà was severely damaged.

Michelangelo was known for shouting at his sculptures and sometimes even striking them with his tools. However, it was a Hungarian geologist, Laszlo Toth, who gained infamy on Pentecost Sunday of 1972 when he jumped over the barriers at St. Peter's Basilica and attacked the Pietà with a hammer. With several blows, Toth broke off Mary's left arm, shattered the tip of her nose, and damaged her cheek and left eye.

10. The attack on the statue was not considered a criminal act.

The authorities chose not to press criminal charges against Toth for his assault on the priceless artwork. However, a Roman court labeled him as 'a socially dangerous person' and committed him to a mental health facility for two years. After his release, Toth was deported.

11. The restoration of the Pietà sparked significant debate.

When art is damaged in such a way, the decision arises as to whether it should be left in its altered state (like Cleveland’s The Thinker, which was damaged in a bombing) or restored to its original form. The Vatican considered three distinct perspectives on this matter.

The first argument suggested that the Pietà’s damage had become part of its message, symbolizing the violence of the modern era. Another camp proposed that the statue be repaired but with visible seams to serve as a reminder of the attack. Ultimately, a seamless restoration was chosen, aiming to erase any trace of Toth’s assault, making it impossible for viewers to know that Michelangelo’s masterpiece had been touched.

12. The restoration process lasted 10 months.

Skilled craftsmen meticulously sifted through the 100 pieces of marble that had been broken from the Pietà, carefully reassembling the statue. Working in a temporary lab built around the sculpture, they spent five months identifying fragments as small as fingernail-sized pieces. After that, they used a transparent adhesive and marble powder to reattach the pieces and fill any gaps with replacement fragments. Once the restoration was finished, the final step was to encase the masterpiece in bulletproof glass for protection.

13. This wasn't the first time the Pietà was protected by bulletproof glass.

In 1964, the Vatican lent the Pietà to the United States for display at the 1964 New York World’s Fair. To protect this priceless artwork, organizers constructed a barrier of seven giant sheets of plexiglass, collectively weighing over 4900 pounds. In addition, conveyor belt-style walkways were installed to ensure safe passage for the crowds admiring the sculpture.

14. The attack on the Pietà had an unexpected silver lining.

While carefully restoring the statue, workers uncovered a hidden signature. In the folds of Mary’s left hand, they found a subtle 'M,' thought to represent 'Michelangelo.'

15. Michelangelo's model for the Pietà may have been identified.

In November 2010, American art historian Roy Doliner suggested that a restored 12-inch statue from the late 15th century, previously misattributed to Andrea Bregno, was actually a prototype by Michelangelo for his Pietà. Doliner argues that this small sculpture of Mary and Jesus was a model created to secure the commission from Cardinal de Billheres.