Zebras are not merely striped relatives of the horse family. Among these creatures, you’ll find skilled climbers, individuals with spots rather than stripes, and even those that produce sounds resembling dogs. Dive into these and other astonishing zebra facts that will captivate your curiosity.

Zebra Species, Habitats, and Unique Traits

Species | Scientific Name | Subspecies | Where It’s Found | Size | Rump Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Plains Zebra | Equus quagga | E. q. crawshaii, E. q. borensis, E. q. boehmi, E. q. chapmani, E. q. burchellii, E. q. quagga | Eastern and southern Africa | 3.5–5 feet tall at the shoulder; 440–990 pounds | Broad bands |

Grevy’s Zebra | E. grevyi | N/A | Ethiopia and northern Kenya | 4–5 feet tall at the shoulder; 770–950 pounds | Chevron triangle |

Mountain Zebra | E. zebra | E. z. hartmannae, E. z. zebra | Namibia and some spots in western South Africa | 3.8–4.9 feet tall at the shoulder; 529–820 pounds | Grid |

A zebra’s striped pattern functions like a massive barcode, and it’s something we can effectively decode.

Each zebra boasts a distinct stripe pattern, which researchers utilize like barcodes to identify and monitor individuals within a herd over time.

Early attempts at identifying zebras by their stripes were far less advanced compared to modern techniques. In the 1960s, Hans and Ute Klingel, a pioneering duo, developed stripe recognition methods for Grevy’s zebras. They photographed numerous zebras, developed the images in a makeshift darkroom on-site, and cataloged each animal’s unique stripe pattern in a handwritten card index. Explore some of their catalog cards here.

Today, advanced software can analyze zebra images and identify individuals by decoding their stripes like barcodes. This technology can even adjust for changes in posture, weight, and pregnancy.

Zebra stripes might function as natural insect repellent or a form of temperature regulation.

For years, researchers have debated the purpose of zebra stripes. One widely accepted theory suggests that the stripes disorient predators, making it difficult for, for instance, a lion to single out one zebra in a fleeing herd.

Recently, more fascinating theories have surfaced. Some researchers propose that stripes help zebras stay cooler. The darker stripes absorb more sunlight than the lighter ones, creating air currents that dissipate heat. Others have found that biting flies tend to avoid striped surfaces. These theories may be connected: since biting flies thrive in heat, they are less likely to target a cooler zebra.

Zebras aren’t always adorned with black and white stripes.

A rare spotted zebra. | Abdelrahman Hassanein/Moment/Getty Images

A rare spotted zebra. | Abdelrahman Hassanein/Moment/Getty ImagesZebras are divided into three species and numerous subspecies, varying in size, body shape, and stripe patterns—sometimes even in color. The white stripes can appear cream-colored, while the dark stripes range from black to brown. Certain subspecies feature faint, shadow-like stripes between the prominent dark ones. Additionally, mutations and variations exist, with some zebras displaying spots or being so pale they appear almost entirely white.

Mountain zebras are known for their toughness.

An adult mountain zebra. | imageBROKER/Juergen & Christine Sohns/Getty Images

An adult mountain zebra. | imageBROKER/Juergen & Christine Sohns/Getty ImagesAmong the three zebra species, the mountain zebra primarily inhabits rocky, elevated regions in South Africa and neighboring Namibia. Its sturdy, sharp hooves are perfectly adapted for climbing and maintaining stability on uneven terrain. While it doesn’t sport a beard, this resilient animal features a distinctive neck flap, known as a “dewlap.”

Plains zebras are smaller in size and abundant in number.

A plains zebra. | Wolfgang Kaehler/GettyImages

A plains zebra. | Wolfgang Kaehler/GettyImagesPlains zebras are the smallest among zebra species and the most widespread, making them the most populous wild members of the horse family. They inhabit vast regions of southeastern Africa.

Plains zebras encompass several subspecies, each displaying unique coat variations. Notably, as you move southward across Africa, these zebras exhibit fewer stripes on their legs. The reason remains unclear, though it may relate to temperature or the presence of biting flies.

Grevy’s zebras are notably larger...

Grevy’s zebras. | Kenneth Whitten / Design Pics/Getty Images

Grevy’s zebras. | Kenneth Whitten / Design Pics/Getty ImagesNative to Kenya and Ethiopia, Grevy’s zebras possess a donkey-like physique with large, rounded ears. They are the biggest wild members of the horse family, weighing up to 990 pounds. (Domestic horses, bred over millennia for various traits, can grow even larger, with some reaching enormous sizes.)

... and they are named after a former French president.

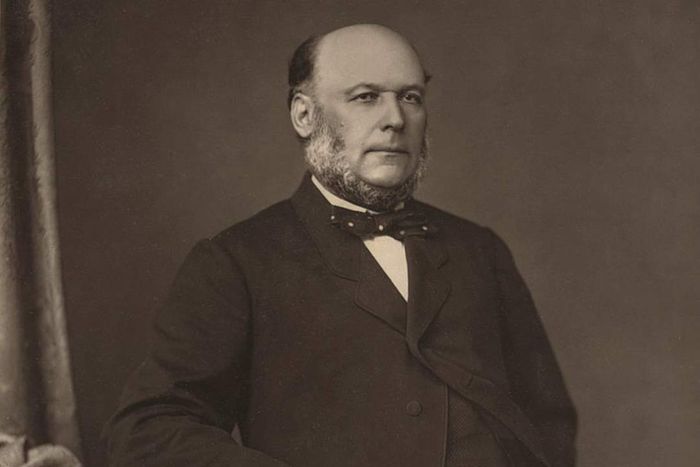

French President Jules Grévy. | Chris Hellier/GettyImages

French President Jules Grévy. | Chris Hellier/GettyImagesIn 1882, Menelik II, Emperor of Abyssinia (modern-day Ethiopia), gifted a zebra of this species to French President Jules Grévy. Since then, these zebras have been named in his honor.

To distinguish between zebra species, examine their hindquarters.

Plains zebras in Kenya's Masai Mara National Reserve. | Anthony Asael/Art in All of Us/GettyImages

Plains zebras in Kenya's Masai Mara National Reserve. | Anthony Asael/Art in All of Us/GettyImagesSeveral key features help differentiate zebra species, one of which is the pattern on their hindquarters. Mountain zebras display a “grid-like” arrangement of thin stripes above their tails. Plains zebras feature wide stripes across their rear, while Grevy’s zebras exhibit a triangular design with numerous fine lines near the tail. Once you recognize these distinctions, identifying them becomes effortless—just be prepared to explain your fascination with zebra rumps to your safari group.

An extinct zebra subspecies lacked stripes on its hindquarters.

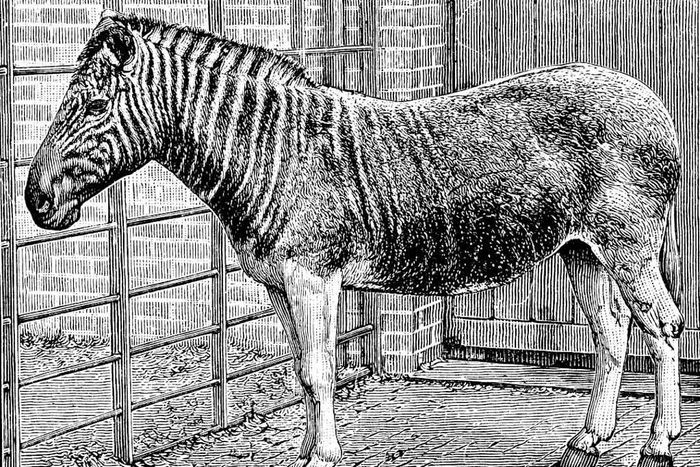

Quagga mare in London Zoo, circa 1870. | Print Collector/GettyImages

Quagga mare in London Zoo, circa 1870. | Print Collector/GettyImagesThe quagga (E. q. quagga), a unique plains zebra subspecies from South Africa, had a predominantly brownish-yellow coat with no stripes below its shoulders. European settlers and hunters drove it to extinction, and the last quagga passed away at the Amsterdam Zoo in 1883.

Remarkably, the Quagga Project in South Africa is attempting to revive this extinct subspecies. By selectively breeding plains zebras that resemble quaggas, they aim to activate any remaining quagga genes. However, the initiative has faced criticism, with some arguing that replicating an animal’s appearance doesn’t equate to restoring its distinct behaviors and ecological significance.

Zebra courtship is far from simple.

Mountain and plains zebras live in small groups led by one stallion and a few mares. This imbalance leaves many males without a herd, so they form bachelor groups. These bachelors may attempt to take over an existing herd, but it’s a challenging process. They must first defeat the dominant stallion, then patiently wait for the females to accept them—a process that can take up to three years.

Grevy’s zebras have a different approach. A mature Grevy’s stallion doesn’t manage a herd; instead, he claims a territory with access to food and water. He waits, hoping wandering females will stop by for resources and potential mating. Young males without territories form groups and roam, tolerated by territorial stallions—until a female arrives, sparking conflict.

Riding a zebra is not advisable.

Seriously, don’t attempt it. Horses were domesticated by humans millennia ago, altering their appearance and temperament to become obedient and cherished companions. Zebras, however, were never domesticated. The contrast is akin to comparing a poodle to a wolf. Several factors, including a zebra’s evasive reflexes, explain why horses were domesticated instead of zebras.

Zebras produce a variety of unique sounds.

Zebras are quite vocal. Mountain zebras whinny like horses, Grevy’s zebras bray like donkeys, and plains zebras emit dog-like barks. When alarmed, stallions may squeal or snort, while content zebras often exhale air through their lips while grazing.

Zebras can hybridize to create zorses, zonies, zedonks, and more.

A zebroid or zorse—a hybrid between a horse and a zebra. | Eric Lafforgue/Art in All of Us/GettyImages

A zebroid or zorse—a hybrid between a horse and a zebra. | Eric Lafforgue/Art in All of Us/GettyImagesZebras can interbreed with other equine species, producing a fascinating array of partially striped offspring, most of which are sterile (unable to reproduce). Zorses result from horse stallions mating with zebra mares. Zedonks are born from zebra stallions and donkey mares. Zonies emerge from zebras and ponies. The possibilities for such unique hybrids are vast.

Zebras are facing significant challenges.

Grevy’s zebras are struggling due to habitat loss, hunting, competition with livestock for resources, and disease. The IUCN classifies them as endangered, noting they’ve experienced “one of the most dramatic range reductions among African mammals.” Only around 2,000 of these large-eared zebras remain.

Mountain zebras are also under threat and are classified as vulnerable, a step below endangered. Their numbers are rising, with approximately 35,000 mature individuals. Plains zebras are listed as near threatened, with a declining population estimated between 150,000 and 250,000.

Plains zebras enhance the quality of grasslands.

For selective grazers like Thomson’s gazelles and wildebeest, zebras are a blessing. Their unique digestive systems allow them to process tougher, less nutritious plants efficiently. Plains zebras often lead the way into untouched grassy areas [PDF], consuming older vegetation that others avoid. This clears the way for fresh, tender growth, attracting more discerning grazers to feast on the new, nutrient-rich plants.