Nicolaus Copernicus, a Polish astronomer and mathematician, revolutionized the way we perceive science. Born on February 19, 1473, he introduced the heliocentric theory, proposing that the planets revolve around the Sun, sparking the Copernican Revolution. Copernicus was also a lifelong bachelor, a member of the clergy, and explored fields like medicine and economics. Discover these 15 fascinating facts about the pioneer of modern astronomy.

1. He was born into a family with roots in both commerce and the church.

Some scholars suggest that Copernicus's surname comes from Koperniki, a village in Poland named after copper traders. His father, also named Nicolaus Copernicus, was a prosperous copper merchant in Krakow. His mother, Barbara Watzenrode, hailed from a powerful merchant family, with her brother, Lucas Watzenrode the Younger, serving as a prominent Bishop. Two of Copernicus’s three older siblings entered the clergy, one becoming a canon and the other a nun.

2. He was a master of many languages.

As a child, Copernicus was likely fluent in both Polish and German. After his father's passing when he was about 10 years old, his uncle, Lucas Watzenrode, supported his education and introduced him to Latin. In 1491, Copernicus began his studies in astronomy, mathematics, philosophy, and logic at Krakow University. Five years later, he traveled to Bologna University in Italy to study law, where he probably learned some Italian. Additionally, he was also familiar with Greek, leading modern historians to believe that he was proficient in five languages.

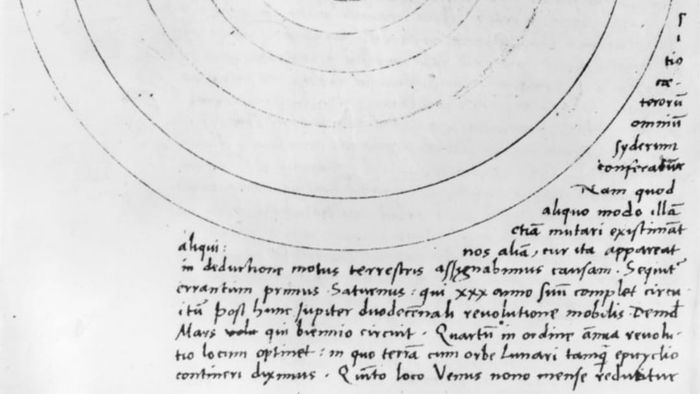

3. He wasn't the first to propose the heliocentric model ...

An illustration from Copernicus's work showing the arrangement of planets around the Sun. | Hulton Archive, Getty Images

An illustration from Copernicus's work showing the arrangement of planets around the Sun. | Hulton Archive, Getty ImagesCopernicus is often credited with pioneering heliocentrism—the revolutionary idea that Earth orbits the sun, as opposed to the sun revolving around Earth. However, the concept was discussed by various Greek and Islamic scholars centuries before Copernicus. For instance, Aristarchus of Samos, a Greek astronomer from the 3rd century BCE, was among the first to propose that the Earth and other planets move around the Sun.

4. … yet he did not fully acknowledge earlier theorists.

It is important to note that Copernicus was aware of the work done by earlier mathematicians. In an early version of his 1543 manuscript, he included references to the heliocentric theories of Aristarchus and other ancient Greek astronomers who had previously entertained similar ideas. However, before publishing, Copernicus chose to remove these passages. The reasons for this are debated, ranging from his desire to present the theory as entirely his own to opting for a ‘more refined’ Greek quote in place of the Latin one, inadvertently omitting Aristarchus’s work. The removed sections weren’t discovered until about 300 years later.

5. His influence extended to economics.

While Copernicus is chiefly remembered for his contributions to mathematics and science, he also made notable strides in economics. In 1517, he authored a paper offering recommendations to the Polish king on how to streamline the country’s various currencies, particularly concerning the debasement of some of them. His work on supply and demand, inflation, and government price controls helped shape later economic theories such as Gresham’s Law (the idea that ‘bad money drives out good’ when both are accepted at the same price) and the Quantity Theory of Money (the concept that the quantity of money in circulation is proportional to the cost of goods).

6. He was a physician (without a formal medical degree).

After studying law, Copernicus went to the University of Padua with the goal of becoming a medical advisor to his ailing uncle, Bishop Watzenrode. Although he spent two years studying medical texts and anatomy, he did not obtain a doctorate in medicine. Nevertheless, he accompanied his uncle on travels, providing medical care to him and other clergy members in need of treatment.

7. He likely remained a bachelor throughout his life …

An engraving of Copernicus, circa 1530. | Hulton Archive, Getty Images

An engraving of Copernicus, circa 1530. | Hulton Archive, Getty ImagesAs a member of the Catholic Church, Copernicus took a vow of celibacy. He never married and was likely a virgin (more on that below). However, children were still a part of his life: After the death of his older sister Katharina, Copernicus became the financial guardian of her five children, his nieces and nephews.

8. … Yet he might have had a relationship with his housekeeper.

Although Copernicus took a vow of celibacy, there are questions about whether he adhered to it. In the late 1530s, when Copernicus was in his sixties, Anna Schilling, a woman in her forties, began living with him. Schilling may have been related to Copernicus—some historians believe she was his great-niece—and she worked as his housekeeper for two years. For reasons unknown, the bishop Copernicus worked under reprimanded him twice for having Schilling live with him, even advising him to dismiss her and writing to other church officials about the matter.

9. He attended four universities before obtaining his degree.

iStock

iStockCopernicus spent more than ten years studying at universities in both Poland and Italy, though he often left before completing his degree. Why did he skip earning diplomas? Some historians believe that during this time, it wasn't uncommon for students to leave university without graduating. Additionally, Copernicus didn’t need a degree to practice medicine or law, serve in the Catholic Church, or pursue higher-level courses.

However, just before returning to Poland, he received a doctorate in canon law from the University of Ferrara. According to Copernicus scholar Edward Rosen, this wasn't necessarily for academic reasons but rather because, as Rosen suggests, ‘to show that he had not wasted his time on wine, women, and song, he had to bring home a diploma. That cost much less in Ferrara than in other Italian universities where he had studied.’

10. He was hesitant to share his ideas with the public.

During Copernicus’s lifetime, the prevailing belief was geocentrism—the notion that the Earth was the center of the universe. Despite this, in the 1510s, Copernicus wrote *Commentariolus* (The Little Commentary), a brief text outlining heliocentrism, which he shared with his friends. It soon spread further, and it’s said that Pope Clement VII heard a talk on this new theory and responded positively. Cardinal Nicholas Schönberg later wrote Copernicus a letter of encouragement. However, Copernicus still hesitated to publish the complete version of his work. Some historians speculate that Copernicus feared ridicule from the scientific community for not fully resolving the challenges heliocentrism posed, while others suggest that with the rise of the Reformation, Copernicus feared the Catholic Church’s increasing repression of dissent. In any case, he didn’t make his complete work public until 1543.

11. He published his work just before his death.

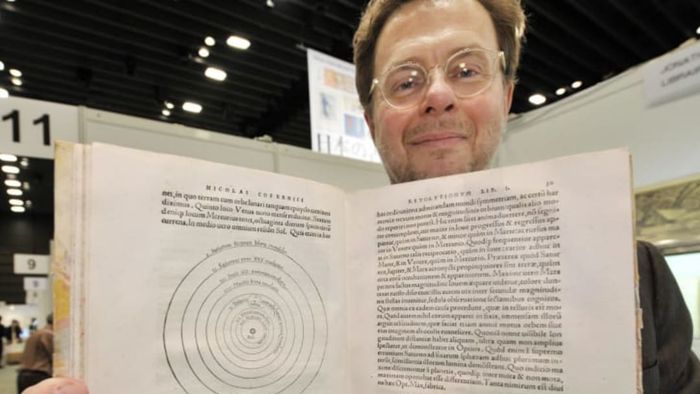

An antique bookseller at the Tokyo International Antique Book Fair on March 12, 2008, displayed a rare first edition of Nicolaus Copernicus' revolutionary work on the planetary system. Published in 1543 and titled *De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium, Libri VI* in Latin, the book includes a diagram that depicts the Earth and other planets revolving around the Sun, directly opposing the widely accepted geocentric theory. | YOSHIKAZU TSUNO, AFP/Getty Images

An antique bookseller at the Tokyo International Antique Book Fair on March 12, 2008, displayed a rare first edition of Nicolaus Copernicus' revolutionary work on the planetary system. Published in 1543 and titled *De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium, Libri VI* in Latin, the book includes a diagram that depicts the Earth and other planets revolving around the Sun, directly opposing the widely accepted geocentric theory. | YOSHIKAZU TSUNO, AFP/Getty ImagesCopernicus completed his book on heliocentrism, *De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium (On the Revolutions of Celestial Orbs)*, during the 1530s. On his deathbed in 1543, he finally chose to publish his contentious work. According to legend, the astronomer awoke from a coma just in time to see pages of his freshly printed book before passing away.

12. Galileo faced consequences for supporting Copernicus' theory.

Copernicus dedicated his book to the Pope, but decades after its publication, the Catholic Church rejected it, placing it on the Index of Prohibited Books in 1616, pending revision. A few years later, the Church lifted the ban after modifying the text to present Copernicus's ideas as speculative. In 1633, 90 years after Copernicus's death, the Church condemned astronomer Galileo Galilei for ‘strong suspicion of heresy’ for supporting Copernicus' heliocentric theory. After spending a day in prison, Galileo was placed under house arrest for the rest of his life.

13. A chemical element bears his name.

If you look at the periodic table, you'll spot an element with the symbol Cn. Known as Copernicium, this element, with atomic number 112, was named in tribute to the astronomer in 2010. Copernicium is a highly radioactive element, with its most stable isotope having a half-life of only about 30 seconds.

14. His remains were discovered by archaeologists in 2008.

iStock

iStockCopernicus passed away in 1543 and was buried somewhere beneath the cathedral where he worked, but the exact location of his grave remained unknown. Archaeologists excavated areas around Frombork Cathedral and in 2005, they uncovered a part of a skull and skeleton beneath the church’s marble floor, near an altar. Three years of forensic facial reconstruction and DNA analysis—comparing DNA from Copernicus's skeleton to hair found in one of his books—confirmed the identity. In 2010, the Polish clergy reburied Copernicus at Frombork.

15. Monuments to Copernicus can be found worldwide.

iStock

iStockA well-known statue of Nicolaus Copernicus, called the Nicolaus Copernicus Monument, stands proudly near the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw, Poland. Replicas of this statue are also located outside Chicago's Adler Planetarium and Montreal's Planétarium Rio Tinto Alcan. In addition to these monuments, Copernicus is honored with a museum and research facility—Warsaw's Copernicus Science Centre—which is dedicated to his legacy.