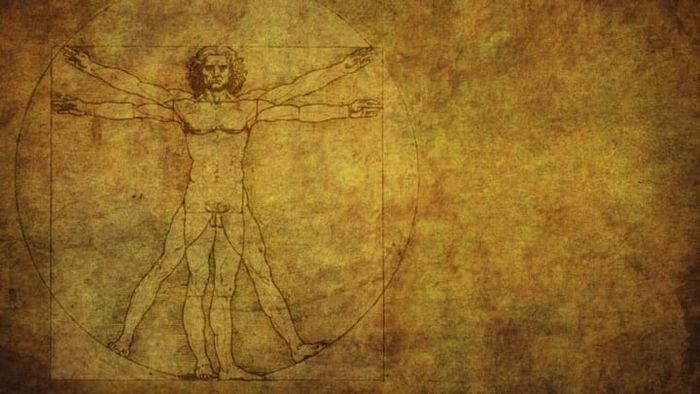

Over the past 500 years, Leonardo da Vinci's Vitruvian Man has transitioned from a detailed sketch to a universal symbol of health. The intriguing history of this illustration is as fascinating as its widespread presence.

1. Vitruvian Man was never meant for public display.

This sketch was found in one of the High Renaissance genius's private notebooks. Created around 1490 as a personal study, Leonardo likely never imagined it would gain such admiration. Today, Vitruvian Man stands as one of his most iconic works, alongside The Last Supper and Mona Lisa.

2. It represents the fusion of art and science.

iStock.com/JanakaMaharageDharmasena

iStock.com/JanakaMaharageDharmasenaA quintessential Renaissance polymath, Leonardo excelled not only as a painter, sculptor, and writer but also as an inventor, architect, engineer, mathematician, and amateur anatomist. This pen-and-ink sketch reflects his study of the human proportion theories proposed by the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius. In his work De Architectura, Vitruvius stated, "If a man lies on his back with his arms and legs outstretched and a compass is centered at his navel, the tips of his fingers and toes will touch the circumference of a circle drawn around him. Similarly, the human body can also fit within a square."

3. Leonardo wasn't the first to try visualizing Vitruvius's concepts.

In a 2012 interview with NPR, American scholar Toby Lester noted, "Particularly in the 15th century, in the years before Leonardo created his drawing, several individuals attempted to visually represent this concept."

4. It might have been a collaborative effort.

In 2012, Italian architectural historian Claudio Sgarbi presented evidence suggesting that Leonardo's proportional study was inspired by a similar work by his friend and fellow Vitruvius admirer, Giacomo Andrea de Ferrara, a contemporary architect. While there's debate over whether they collaborated, historians agree that Leonardo refined and corrected flaws in Giacomo's version, such as adding a second set of arms and legs to better align with Vitruvius's descriptions.

5. The circle and square symbolize a deeper significance.

In their mathematical pursuits, Vitruvius and Leonardo sought to uncover not only human proportions but also the ratios of the entire cosmos. In a 1492 notebook, Leonardo reflected, "The ancients referred to man as a miniature world, and this title is fitting, as man, composed of earth, water, air, and fire, mirrors the elements of the earth itself." Essentially, man represents a microcosm of the universe.

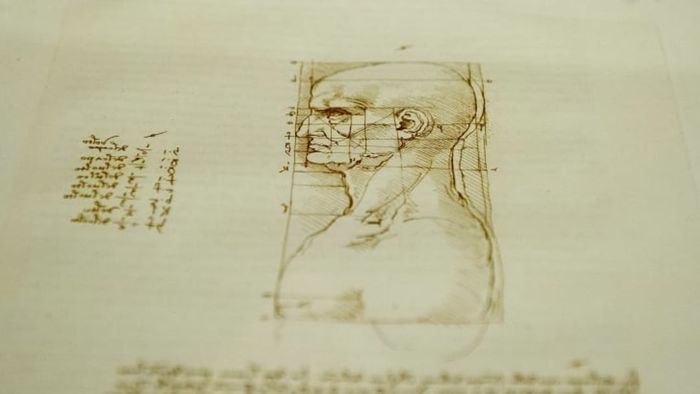

6. It belongs to a collection of sketches.

Marco Secchi/Getty Images

Marco Secchi/Getty ImagesLeonardo created numerous sketches of people, measuring their proportions to enhance his artistic skills and deepen his understanding of the human form and the natural world.

7. Vitruvian Man represents the ideal male form.

The model's identity remains unknown, but art historians suggest Leonardo took artistic liberties in his depiction. Rather than a portrait, the drawing represents an idealized male form, meticulously crafted through mathematical precision rather than real-life inspiration.

8. It might be a self-portrait.

Based on limited descriptions of Leonardo as a young man, some art historians propose that Vitruvian Man could be a representation of the artist himself. As Lester explained to NPR: "He was described as well-built, strong, strikingly handsome, with shoulder-length curly hair. A surviving sculpture from Florence and a fresco in Milan offer possible depictions of him, both resembling the figure in the drawing." However, he acknowledged that certainty is impossible.

9. Vitruvian Man may have had a hernia.

Surgical lecturer Hutan Ashrafian proposed this diagnosis 521 years later, identifying an inguinal hernia. Ashrafian speculated that such a condition could have been fatal for the model, and if Leonardo based the figure on a cadaver, the hernia might have been the cause of death.

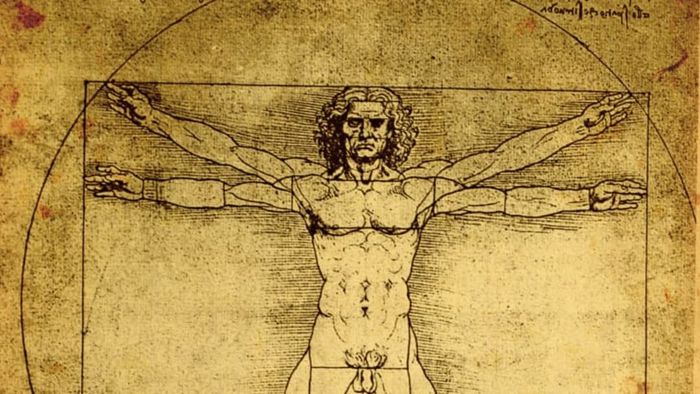

10. The surrounding notes provide essential context.

iStock.com/JanakaMaharageDharmasena

iStock.com/JanakaMaharageDharmasenaOriginally part of a notebook, Vitruvian Man was accompanied by handwritten notes detailing observations on human proportions. Translated into English, they include: "Vitruvius, the architect, states in his architectural work that human body measurements are naturally proportioned: 4 fingers equal 1 palm, 4 palms equal 1 foot, 6 palms equal 1 cubit, and 4 cubits equal a man's height. Additionally, 4 cubits make one pace, and 24 palms define a man's proportions, which he applied in his architectural designs. If you spread your legs to reduce your height by 1/14 and extend your arms until your middle fingers align with the top of your head, the center of your limbs will be at the navel, and the space between your legs forms an equilateral triangle. The span of a man's outstretched arms equals his height." [PDF]

11. The figure is marked with measurement lines.

Observe the man's chest, arms, and face. Leonardo used solid straight lines to indicate proportional measurements, as referenced in his notes. For example, the distance from the ears or bottom of the nose to the eyebrows constitutes the top third of the face, while the bottom of the nose to the chin forms the lower third, and the eyebrows to the hairline complete the upper third.

12. It is also known by simpler titles.

The sketch is alternatively referred to as Canon of Properties or Proportions of Man.

13. Vitruvian Man features 16 distinct poses.

At first glance, only two poses may be visible: standing with feet together and arms outstretched, and standing with feet apart and arms raised. However, Leonardo's brilliance lies in the overlapping body positions, which reveal 16 possible combinations of these extended limbs.

14. It has been adapted to convey a political statement.

Linking Vitruvian Man's connection between humanity and nature, large-scale artist John Quigley reimagined the iconic image to highlight the urgency of global warming. While images of melting ice often fail to resonate, Quigley's 2011 creation of Melting Vitruvian Man on a vast ice floe brought the issue to life on an unprecedented scale. His copper strip rendition spans four times the length of an Olympic swimming pool.

15. The original sketch is seldom displayed publicly.

While reproductions are widespread, the original is too delicate and significant for permanent exhibition. Vitruvian Man is usually stored securely at the Gallerie dell'Accademia in Venice. A 2013 exhibition marked the first public viewing in 30 years, and in 2019, the Gallerie hosted a 3-month exhibition commemorating the 500th anniversary of Leonardo's death. Otherwise, viewing the masterpiece requires special permission for a private session at the Office of Drawings and Prints.