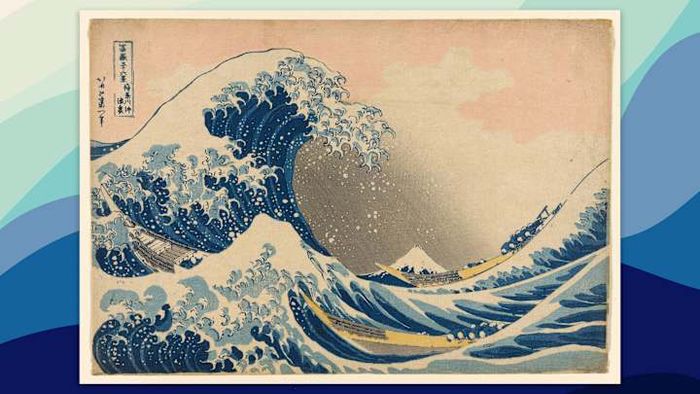

Katsushika Hokusai’s The Great Wave off Kanagawa masterfully transforms the ocean’s immense force into a strikingly simple yet hypnotic two-dimensional depiction. However, the hidden depths of this iconic 19th-century masterpiece might astonish you.

1. While it’s famous for its wave, it secretly features a mountain.

Shift your gaze slightly to the right of center. What appears to be another towering wave is, in fact, the snow-covered peak of Mount Fuji, Japan’s tallest mountain.

2. It’s part of a print series, not a standalone painting.

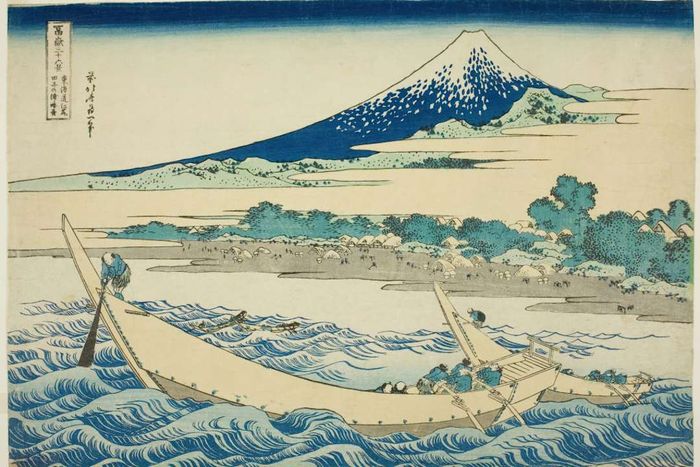

Tago Bay Near Ejiri On The Tokaido (Tokaido Ejiri Tagonoura Ryakuzu) is among the prints featured in ‘Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji.’ | Heritage Images/GettyImages

Tago Bay Near Ejiri On The Tokaido (Tokaido Ejiri Tagonoura Ryakuzu) is among the prints featured in ‘Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji.’ | Heritage Images/GettyImagesWhile Hokusai was skilled in painting, the artist—who thrived during Japan’s Edo period (1603-1868)—gained renown for his woodblock prints. The Great Wave off Kanagawa stands as the most celebrated piece from his Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji collection. Each print, bursting with vivid colors and masterful spatial composition, offers a unique perspective of the majestic peak in diverse settings.

3. Creating this series was a strategic business decision.

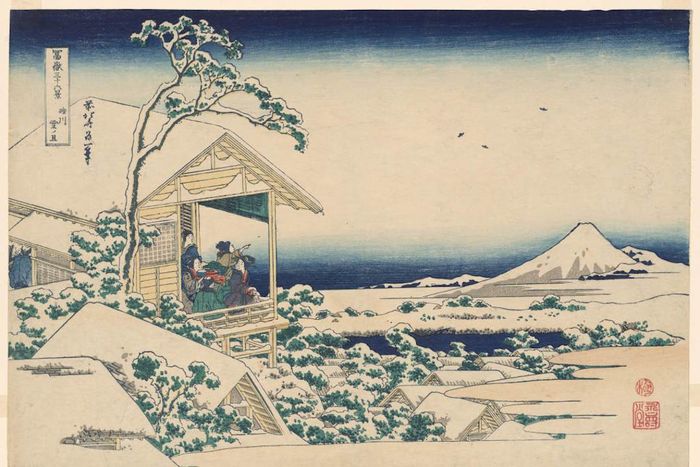

Snowy Morning From Koishikawa (Koishikawa Yuki No Ashita), another piece from the ‘Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji’ collection. | Heritage Images/GettyImages

Snowy Morning From Koishikawa (Koishikawa Yuki No Ashita), another piece from the ‘Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji’ collection. | Heritage Images/GettyImagesMount Fuji, revered as sacred by many, has sparked a devoted following. Producing a series of portrait prints, which could be easily mass-produced and sold affordably, was a strategic move. As tourism to Japan grew, these prints experienced a revival, becoming highly sought-after souvenirs, particularly those showcasing the iconic mountain.

4. Hokusai had six decades of painting experience before crafting this Wave.

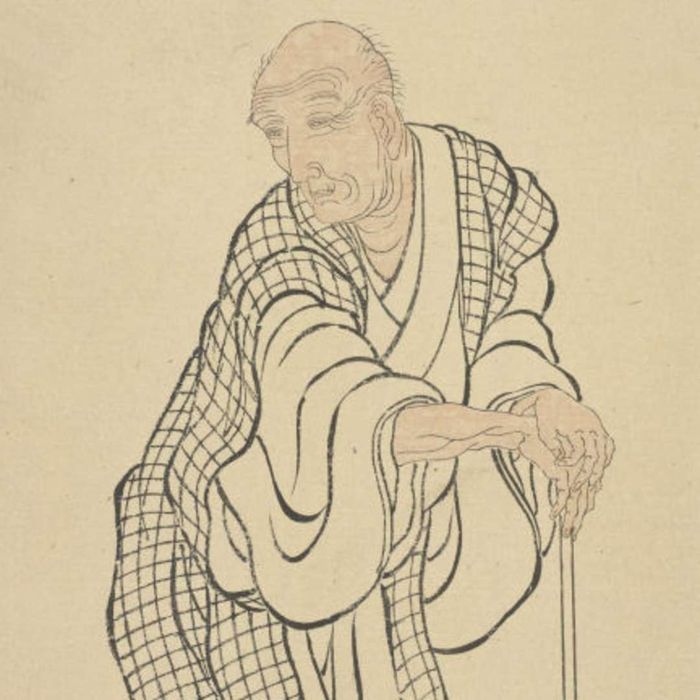

Hokusai As An Old Man | Heritage Images/GettyImages

Hokusai As An Old Man | Heritage Images/GettyImagesHokusai’s precise age during the creation of The Great Wave off Kanagawa remains uncertain, but most historians agree he was in his seventies. He started painting at 6, and by 14, he worked

5. The Great Wave off Kanagawa is displayed in museums worldwide.

As a woodblock print, numerous copies of The Great Wave exist, making it accessible in museums around the world. Notable locations include The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, the British Museum in London, the Art Institute of Chicago, LACMA in Los Angeles, the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, and even Claude Monet’s frequently depicted home and garden.

6. Japan initially slowed the global recognition of this Wave.

The Great Wave off Kanagawa was likely produced between 1829 and 1832, a time when Japan’s cultural exchanges were limited to controlled trade with China, Korea, and the Dutch, who were confined to Nagasaki. It wasn’t until nearly three decades later, under political pressure, that Japan opened its ports to foreign nations. By 1859, Japanese prints, including this masterpiece, flooded Europe, earning admiration from figures like Vincent Van Gogh, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, and Claude Monet.

7. Japanese politicians and art historians didn’t consider it true art.

While The Great Wave off Kanagawa became a symbol of Japanese art globally, within Japan, woodblock prints were not regarded as high art. As art historian Christine Guth from the University of London told the BBC, they were seen as a commercial and popular medium, often used for Buddhist texts, poetry, and romance novels. This led to reluctance among Japan’s elite to embrace it as a representation of their culture.

8. The Great Wave off Kanagawa reflects more than just Japanese influences.

Hokusai drew inspiration from European art, particularly the linear perspective techniques found in Dutch works. This influence is visible in the low horizon line of the print. Additionally, his use of Prussian blue, a pigment popular in Europe at the time, further highlights the blend of Eastern and Western artistic traditions.

9. Earlier prints are considered more valuable.

Between 5000 and 8000 copies of The Great Wave off Kanagawa were produced. Over time, the woodblocks used for printing deteriorated, leading to a decline in image quality. This is why museums emphasize owning “early” editions, as they represent the print in its finest form.

10. Once inexpensive, these prints now command high prices.

Despite thousands being printed, only a few hundred copies of The Great Wave off Kanagawa survive today. The condition of a print significantly affects its worth. Early editions from Nishimuraya Yohachi featured a unique blue outline, while later versions had a black outline. In 2015, early editions were valued at $40,000 to $60,000, with later ones fetching half that amount. Even high-quality replicas can sell for thousands.

11. The print carries a double signature, in a sense.

In the upper left corner of the print, a box contains text both inside and outside. Inside, Hokusai inscribed the title of the piece and its position in the Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji series. To the left, he added “Hokusai aratame Iitsu hitsu,” which means “From the brush of Hokusai, now Iitsu.” Throughout his career, Hokusai adopted over 30 different names, each marking a distinct phase of his artistic journey.

12. It influenced musical compositions.

French composer Claude Debussy credited his orchestral piece The Sea (La Mer) with inspiration from The Great Wave off Kanagawa. The 1905 sheet music edition featured a sketch reminiscent of the iconic print, offering listeners a visual connection to his symphonic work. You can hear a performance of it above.

13. The series featuring The Great Wave off Kanagawa also inspired poetry.

Bohemian-Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke, moved by Hokusai’s dedication, penned the poem “The Mountain.” It begins, “Six and thirty times and hundred times/the painter tried to capture the mountain,/tore it up, then pushed on again/ (six and thirty times and hundred times).”

14. The print inspired a modern emoji.

Although the wave emoji varies in appearance across devices, Apple’s version, introduced in 2008, was clearly influenced by Hokusai’s Great Wave.

15. The wave depicted is not a tsunami.

The towering wave dwarfs Mount Fuji and threatens the boats below, leading many to mistake it for a tsunami. However, researchers Julyan H.E. Cartwright and Hisami Nakamura analyzed the print and concluded it represents a rogue wave, scientifically known as a “plunging breaker.”

16. Despite not being a tsunami, the wave is still dangerous.

Rogue waves, also called freak waves, monster waves, or killer waves, appear suddenly in the open sea and can capsize large ships. The size of the rogue wave in The Great Wave off Kanagawa can be estimated using the three fishing boats (oshiokuri-bune) as reference. Cartwright and Nakamura calculated that the wave stands approximately 32 to 39 feet high.