In the history of horror cinema, few sequels have faced as much backlash as Halloween III: Season of the Witch did upon its 1982 release.

The sci-fi horror film, which (spoiler!) revolves around a sinister toy company’s plan to use children in a Halloween night ritual, marked a stark departure from John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978). That groundbreaking slasher film helped define the modern slasher genre, but Season of the Witch shares little in common with its predecessor or the hospital-set Halloween II from 1981.

The most common complaint from critics and fans was straightforward: Where was Michael Myers? The iconic white-masked killer is completely missing from Season of the Witch, along with Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis’s legendary final girl) and Dr. Sam Loomis (Donald Pleasence). To make matters worse, the film barely features any butcher knives.

However, what one generation dismisses as trash often becomes another’s cherished guilty pleasure. Much like Carpenter’s The Thing—a polarizing sci-fi horror film from 1982 that critics initially rejected—Season of the Witch needed decades to find its audience and earn the recognition it likely always deserved. Below are more intriguing details about the contentious third entry in the Halloween franchise.

1. John Carpenter and Debra Hill joined the project solely because they could avoid focusing on Michael Myers.

Carpenter and Halloween co-writer/producer Debra Hill were approached about a third film shortly after Halloween II’s release. They reportedly began working on the project within days of the slasher sequel’s debut on October 30, 1981—a film Carpenter later described as “an abomination” (despite its $25.5 million U.S. box office earnings).

They agreed to a third Halloween film on the condition that they could steer the story away from Michael Myers and exclude Carpenter from direct involvement. He remained as a producer but declined to write or direct, allowing him to focus on The Thing, which was still in principal photography during Halloween II’s Fall 1981 release and hit theaters in June 1982.

In a 1984 interview, where he labeled Halloween II “an abomination,” Carpenter also shared his mindset during the franchise’s development. “When they offered me the sequels to Halloween, I let my producer’s instincts take over. They offered a substantial amount of money, and I also wanted to give new directors opportunities, just as I had been given a chance with low-budget films,” he explained.

2. Season of the Witch was originally planned as part of an anthology series.

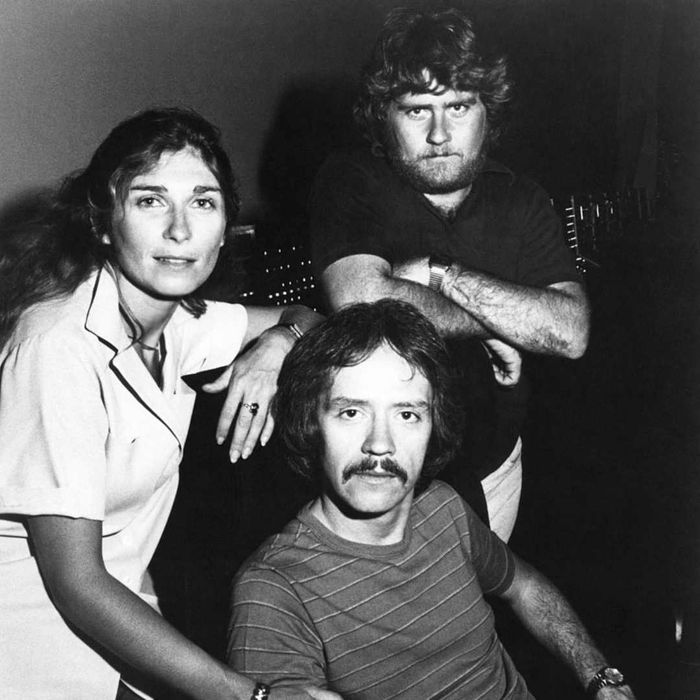

Carpenter, pictured here with Hill on the 'Escape From New York' set, initially had no desire to revisit the Halloween franchise. | Sunset Boulevard/GettyImages

Carpenter, pictured here with Hill on the 'Escape From New York' set, initially had no desire to revisit the Halloween franchise. | Sunset Boulevard/GettyImages“It’s a pod movie, not a slasher film,” Hill explained to The New York Times in 1982 when discussing the third installment of the Halloween series. However, the journey to create Season of the Witch was far from simple—it was, in fact, quite groundbreaking.

Instead of rehashing the tale of a knife-wielding killer, Carpenter and Hill envisioned turning the franchise into a feature-length horror anthology. Director Tommy Lee Wallace revealed they aimed to emulate the style of Night Gallery or The Twilight Zone. Unlike those TV series or films like 1982’s Creepshow, which featured multiple short stories, they wanted each Halloween film to tell a unique, standalone tale—a bold and unconventional approach for the era.

“I mistakenly believed—this shows how naive I was—that we had exhausted the stories about Michael Myers and the masked killer. I thought there wasn’t much left to explore,” Carpenter shared with The Hollywood Reporter in 2017. “So we decided to introduce a fresh story each year. We could still call it Halloween, but it wouldn’t have to involve Michael Myers.”

3. Joe Dante was initially chosen to direct the film.

Though Wallace ultimately directed the movie, he wasn’t the first choice for the role. Carpenter and Hill originally approached Joe Dante, who was gaining recognition with cult classics like 1979’s Rock ‘n’ Roll High School (featuring Halloween star P.J. Soles) and The Howling (1981).

Dante agreed but withdrew just weeks before filming was scheduled to begin in April 1982, opting instead to direct a segment for 1983’s Twilight Zone: The Movie (he handled the third story, inspired by the season 3 episode, “It’s a Good Life”).

To replace him, Hill and Carpenter brought in Wallace. Carpenter and Wallace had been friends since childhood, and Wallace had previously served as the art director and production designer for the original Halloween, even portraying Michael in the iconic closet scene. He had declined the director role for Halloween II due to his dislike of the script and its excessive violence. With Season of the Witch, Wallace made his directorial debut (he later directed the 1990 TV adaptation of Stephen King’s It, starring Tim Curry).

4. The initial screenplay was penned by Nigel Kneale, the creator of Quatermass.

Before Dante left Season of the Witch, he reportedly suggested Nigel Kneale for the script. The acclaimed British writer, famous for the BBC’s Quatermass series from the 1950s (which Carpenter was said to admire), was in Hollywood at the time, collaborating with director John Landis on a script for a Creature from the Black Lagoon remake that never materialized.

Kneale met with Dante and agreed to the project, intrigued by the idea of crafting a story entirely distinct from the previous Halloween films. “Dante proposed that I create a treatment based on the concept of Halloween. Coming from the Isle of Man, where Halloween is a significant event marking the Celtic new year, I developed a story about shops overflowing with plastic masks and Halloween merchandise, reflecting its massive commercial presence in America,” Kneale explained to Starburst Magazine in 1983.

Kneale also introduced the idea of blending witchcraft with sci-fi elements. “In the past, a witch needed direct contact to cast a curse. With modern technology like microchips, a spell could be transmitted through Halloween products,” he said, referencing the “trademark stamp” concept, akin to the medallion that triggers the horror in the final film.

5. Kneale later insisted on having his name removed from the credits.

Kneale was allotted six weeks to write the script, but by that time, Dante had exited, and Wallace had taken over. While some elements of Kneale’s story—such as a sinister mask-maker using microchips to unleash Halloween havoc—were well-received, Wallace and Carpenter believed other parts wouldn’t resonate with young American viewers.

“It felt like he was still crafting stories for 1950s British television,” Wallace told Den of Geek in 2022. “I don’t mean that negatively … His version was unsettling and had intriguing elements, but it leaned more toward a psychodrama than a straightforward horror film.”

Producer Dino De Laurentiis shared this sentiment, insisting the film needed more gore and violence. Wallace and Carpenter made extensive changes to the script, though Wallace estimated that roughly 60 percent of Kneale’s original ideas remained in the final cut.

Despite this, Kneale was reportedly furious. “I couldn’t recognize anything from my original work, and poor Tommy Wallace was tasked with rewriting it. It was stripped down to cardboard sets and a minimal cast. So, I removed my name from it,” he stated.

6. The Silver Shamrock jingle originated from an old nursery rhyme.

How many days remain until Halloween? You can begin your holiday countdown with the infamous jingle from the Silver Shamrock commercial, which plays incessantly throughout the film.

However, it’s not just an earworm due to its repetition. While most of the film’s score was original, composed by Carpenter and Alan Howarth (who also worked with the director on Escape from New York, They Live, and others), the Silver Shamrock jingle stands out because it’s largely based on the classic nursery rhyme, “London Bridge Is Falling Down.”

Wallace explained that he was instructed to “use something in the public domain or create something new” for the jingle, as there were no funds to license existing music. “I knew ‘London Bridge’ was definitely in the public domain, so that was no issue.” He merged it with “The Spinning Song,” a piano piece he recalled from his youth, and provided the vocals himself.

After recording multiple versions, Wallace sped them up and layered them to create a tune he described as “sounding like deranged dwarves in a padded cell.” Yet, he believed it fit the film perfectly, especially since it “relentlessly sticks in your head.”

7. Only one of the iconic Silver Shamrock masks was custom-made for the movie.

The skull mask shown here was one of three masks prominently featured in the movie. | Scream Factory

The skull mask shown here was one of three masks prominently featured in the movie. | Scream FactoryThough not exactly MacGuffins—elements that propel the plot without deeper significance—the Silver Shamrock masks are central to Season of the Witch and a major reason for its lasting cultural impact.

Three masks were used: a lime-green witch with a hood, a glowing skull, and a vibrant orange pumpkin head. Each is strikingly unique, even by modern standards, and were crafted by special effects artist Don Post Jr., whose father, Don Sr., earned the title “Godfather of Halloween” for pioneering the latex mask industry in the 1930s.

The witch and skull masks were based on existing Don Post Studio designs, with the skull model available in stores since the late 1960s. The jack-o’-lantern mask, however, was custom-made for the film and initially painted with Day-Glo.

“Since the masks play such a pivotal role in [Season of the Witch], they could become cult favorites, with fans eager to wear them while watching the movie,” Post explained to The New York Times in 1982. The arrangement also benefited Post: with limited funds for props, producers agreed to share merchandising profits in exchange for his contributions to the film.

8. Those masks are still available for purchase online.

Ask any horror enthusiast what stands out most about Halloween III: Season of the Witch, and the iconic Silver Shamrock masks will likely be mentioned (if not the jingle first). Far from mere memorabilia, these masks—priced at $25 in 1982 (around $76 today)—are central to the film’s storyline and have since become prized collector’s items.

At Trick or Treat Studios, you can find officially licensed replicas of the skull, witch, and pumpkin masks. Starting at around $50, each mask includes a Silver Shamrock medallion. While the medallion won’t—spoiler alert—emit laser beams or turn your head into a snake- and insect-infested mess like in the movie, it’s probably best not to tamper with it, just in case.

9. A milk-bottling facility was used for exterior shots of the Silver Shamrock Novelties factory.

Unlike its predecessors, Season of the Witch is set in California rather than Haddonfield, Illinois. While the story takes place in the fictional town of Santa Mira, filming occurred in Loleta, a small coastal town in Northern California. The production team utilized local landmarks, such as the Familiar Foods milk-bottling plant, which served as the exterior for the Silver Shamrock Novelties factory. (Explosions and smoke effects were prohibited inside the plant, so those scenes were filmed at Post’s studio.)

10. The film includes several nods to Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

Season of the Witch diverges from the slasher formula of earlier Halloween films, blending sci-fi with pagan themes. However, some critics argued it borrowed too heavily from classic sci-fi films, particularly the 1956 version of Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Others, however, viewed these similarities as intentional homages rather than imitation.

The influence of the 1950s Invasion of the Body Snatchers is undeniable. Hill chose to name the town Santa Mira, mirroring the fictional town in Body Snatchers. Additionally, the film’s nihilistic ending pays tribute to Don Siegel’s classic, which also concluded on a similarly ambiguous note.

“It was the perfect ending for the film and my personal tribute to Don Siegel’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers,” Wallace told Den of Geek. Despite the studio’s disapproval—even involving Carpenter to persuade Wallace to alter it—he stood firm and remains proud of the decision. “I believed it elevated the film to true horror,” he said.

11. Stacey Nelkin was cast at the last minute (and initially had no interest in the role).

Before landing her role in 'Halloween III: Season of the Witch,' Nelkin primarily worked in television and comedy. | Bobby Bank/GettyImages

Before landing her role in 'Halloween III: Season of the Witch,' Nelkin primarily worked in television and comedy. | Bobby Bank/GettyImagesSeveral of Carpenter’s frequent collaborators appear in Season of the Witch. Tom Atkins, who plays Dr. Dan Challis, had previously starred in The Fog (1980) and Escape from New York (1981). However, the cast also included newcomers, most notably Stacey Nelkin, who portrays Ellie Grimbridge, a determined young woman investigating her father’s suspicious death.

Prior to her role in the film, Nelkin had focused on television work. She learned about the part from a makeup artist on set, who mentioned the production was struggling to fill the role.

“They were nearing the start of filming and still hadn’t found the lead actress. He kept asking, ‘Stacey, would you be interested?’ I wasn’t initially. I was focused on comedies and other projects at the time,” Nelkin shared in a 2015 interview with CrypticRock. However, after reading the script, she reportedly “fell in love with the character.” Within a week of landing the role, she began filming, cementing her place in ‘80s horror history.

12. Jamie Lee Curtis provided uncredited voice work.

While Laurie Strode doesn’t appear in the film, Jamie Lee Curtis still contributed her voice to 'Season of the Witch.' | Sunset Boulevard/GettyImages

While Laurie Strode doesn’t appear in the film, Jamie Lee Curtis still contributed her voice to 'Season of the Witch.' | Sunset Boulevard/GettyImagesDiscussing the Halloween franchise inevitably involves Jamie Lee Curtis. The future Oscar winner was just 20 when she debuted in the original Halloween. By the time Season of the Witch was in production, she had starred in several other horror films, including The Fog, Terror Train, and Prom Night (all released in 1980), as well as 1981’s Halloween II (which earned her $100,000, equivalent to about $355,000 today).

Despite surviving her hospital showdown with Michael in the second film, Laurie Strode—Curtis’s iconic final girl—doesn’t appear in Season of the Witch. This was partly due to the film’s departure from the previous storyline. Another factor? Curtis was actively avoiding typecasting at the time, a goal she achieved with 1983’s Trading Places.

However, Curtis does have an uncredited cameo in Season of the Witch. Her voice can be heard in a few scenes, including as a telephone operator and the Santa Mira curfew announcer. She didn’t officially return to the franchise as Laurie until 1998’s Halloween H20, and has since appeared in every new Halloween film, excluding Rob Zombie’s 2007 remake and its 2009 sequel (also titled Halloween II).

13. Tommy Lee Wallace also provided uncredited voice work.

Next time you hear the Silver Shamrock commercials, listen closely: Wallace is the voice of the announcer. | Rick Kern/GettyImages

Next time you hear the Silver Shamrock commercials, listen closely: Wallace is the voice of the announcer. | Rick Kern/GettyImagesCurtis wasn’t the only one to go uncredited in Season of the Witch. The announcer in those infectious Silver Shamrock commercials—urging children to don their masks for the “Big Giveaway” on Halloween night—was actually the film’s director, Tommy Lee Wallace.

14. Dan O’Herlihy wasn’t impressed with the final film.

To embody the sinister Conal Cochran, the film’s Samhain-worshiping villain, producers chose veteran actor Dan O’Herlihy, who had previously earned an Oscar nomination for his role in Luis Buñuel’s 1954 adaptation of Robinson Crusoe.

O’Herlihy, born in County Wexford, Ireland, reportedly enjoyed using his native accent in the film. “Whenever I use a Cork accent, I’m having fun, and I used a Cork accent in [Halloween III],” he said in an interview. However, he wasn’t fond of the final product, stating, “I thoroughly enjoyed the role … but I didn’t think it was much of a picture, no.”

15. Season of the Witch was the lowest-grossing Halloween film at the time of its release.

Even late '80s Michael Myers is better than no Michael at all. | Sunset Boulevard/GettyImages

Even late '80s Michael Myers is better than no Michael at all. | Sunset Boulevard/GettyImagesSeason of the Witch premiered on October 22, 1982, perfectly timed for Halloween. Despite this, it struggled at the box office, earning around $6.3 million during its opening weekend—a drop from the $7.4 million Halloween II made in its debut a year earlier.

The film’s earnings didn’t improve significantly after its opening weekend, ultimately grossing about $14.4 million. This made it the lowest-grossing entry in the Halloween franchise until Halloween V: The Revenge of Michael Myers (1989), which only brought in around $11.6 million.

While the franchise has grown (with 13 films to date), The Revenge of Michael Myers and Season of the Witch remain the two lowest-earning films in the 45-year-old series. The film between them—1988’s Halloween IV: The Return of Michael Myers—marked the return of the iconic killer and earned approximately $6.8 million during its opening weekend, with a total of $17.7 million during its theatrical run.

16. Critics initially panned it, but it has since gained cult classic status.

While Season of the Witch has become a cult favorite in recent years, critics at the time were far from kind. Roger Ebert gave it 1.5 stars, calling it a “low-rent thriller from the start,” and The New York Times’s Vincent Canby criticized its “comically bad special effects,” noting it managed to be “anti-children, anti-capitalism, anti-television, and anti-Irish all at once.”

Wallace believes the film’s poor reception was largely due to what it lacked rather than its content. “Many were upset, even angry, that Michael Myers didn’t appear, and there was no knife or Jamie Lee Curtis,” he told Den of Geek. He admitted the backlash was crushing: “I was demoralized. I took it personally and felt like a failure. The Halloween title was both a blessing and a curse ... but Season of the Witch wouldn’t have been made without it.”

Modern critics have been far more favorable. Jim Knipfel from Den of Geek called it a “tight sci-fi horror mystery,” and Benjamin H. Smith of Decider argued it’s “better than its reputation suggests, embodying the essence of a classic ’80s sci-fi horror thriller.” For Wallace, this reevaluation has been a “healing balm” and has significantly improved his view of the film.

17. A graphic, bestselling novelization was also released.

Movie novelizations—essentially films translated into books—were highly popular in the 1970s and ‘80s. From Star Wars to The Terminator, nearly every sci-fi film of the era had one to accompany its theatrical release, and Season of the Witch was no different.

Released by Jove Books in 1982, the Season of the Witch novelization was penned by renowned fantasy-horror author Dennis Etchison under the pseudonym Jack Martin (who also wrote the novelization for Halloween II). While the film struggled with critics and audiences, the novel became a bestseller. It also included more graphic details about certain events, such as the fate of Little Buddy (played by Brad Schacter) and his parents, which some readers felt added depth and weight to the story. Today, paperback copies are highly sought after, selling for $80 to $124 on Amazon.

18. Season of the Witch is a standalone film—yet it remains part of the franchise’s broader mythology.

While the Silver Shamrock masks aren’t central to later Halloween films, they do appear. All three masks can be seen in Halloween (2018) and again in 2021’s Halloween Kills.

Some fans theorize a deeper, meta connection between the film and the rest of the series. In one scene in Season of the Witch, a commercial for the original Halloween plays in a bar, leading some to speculate that the first two films exist as fictional works within the “real world” of the third film.

Another theory centers on Cochran’s cult, suggesting that Season of the Witch might not have marked their end. The Cult of Thorn, a group of Druids, causes chaos around Halloween in 1995’s Halloween: The Curse of Michael Myers (featuring Paul Rudd), leading some fans to speculate they might be connected to Cochran’s group.

The key evidence, according to this theory, is the character of Mrs. Blankenship. In Season of the Witch, Cochran receives a call from a Mrs. Blankenship, though she never appears on screen. In The Curse of Michael Myers, another Mrs. Blankenship (Janice Knickrehm)—possibly the same person—runs a boarding house near the Myers home and is revealed to have babysat Michael as a child, as well as being a member of the Cult of Thorn.

While none of these theories has been officially confirmed or debunked, they add intriguing layers to what is otherwise considered a standalone film within the broader Halloween franchise.