The initial Dodge Monaco shared nearly identical front-end styling with its counterparts, the Custom 880 and Polara Series.

The initial Dodge Monaco shared nearly identical front-end styling with its counterparts, the Custom 880 and Polara Series.Highlights

- The 1965-1968 Dodge Monaco and Monaco 500 aimed to replicate the acclaimed style of the Pontiac Grand Prix.

- Dodge's strategy involved introducing the new 'Monaco' name and a distinctive taillight design.

- Despite these efforts, the Dodge Monaco struggled against fierce competition and was discontinued by 1969.

The Pontiac Grand Prix of the 1960s exuded a unique charm that other automakers aspired to emulate. While the essence of its appeal was hard to pin down, Detroit manufacturers, including Dodge, were determined to capture it. This ambition led to the creation of the 1965-1968 Dodge Monaco and Monaco 500.

Despite their best efforts, the 1960s were dominated by Pontiac, much to the disappointment of other mid-range car manufacturers. Starting in 1957, when Bunkie Knudsen removed the iconic "Silver Streak" hood trim, Pontiac began its ascent. A blend of attractive design and effective marketing quickly propelled the "Wide Track" brand to a solid third place in overall industry sales.

Established rivals like Dodge and Mercury had to work hard to remain competitive, especially since both nearly exited the mid-priced market during 1961-1962, allowing Pontiac to claim most of the profits and recognition. While Mercury's attempt to rival Pontiac is a separate tale, Dodge's strategy involved introducing the new Monaco name and the contributions of Jeffrey Godshall, one of the "Dodge Boys" in the design studios.

"In early February 1963, during one of the coldest winters the Midwest had ever seen, I accomplished a dream I'd had since I was 14: becoming a designer (or 'stylist,' as it was called then) for Chrysler Corporation," Godshall recalls. "It took eight long months after graduating from the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh, but I finally secured the job I had always wanted. After a brief period in a general orientation studio under Dick Macadam (who later succeeded Elwood Engel as Chrysler's design vice-president), I was assigned to the Dodge Exterior Studio for my first production project."

"I was fortunate to land such a coveted role," he adds, "considering the fierce competition between Dodge and Plymouth, which was deeply felt by their designers. By mid-1963, the Dodge studio was finalizing its 1965 models, referred to as the 'A' series in Chrysler Engineering terms. Against one wall was the clay model of the new B-body Coronet, the most plain-looking car I'd ever encountered. In the middle of the studio, work was underway on a refreshed A-body Dart. However, the standout was the big C-body Dodge, positioned on a platform at the far end of the room."

Dodge's Auto Design in the Early 1960s

By early 1963, the general design of the 1965 large Dodges was clear, but the specific appearance of the planned flagship hardtop remained undecided.

By early 1963, the general design of the 1965 large Dodges was clear, but the specific appearance of the planned flagship hardtop remained undecided.The new Dodge C-body marked the first major redesign of a full-size Dodge since the 122-inch-wheelbase Polara/Matador of 1960-1961, when Dodge made a significant impact in the affordable car market with the high-value Dodge Dart. However, the overwhelming success of the Dart in 1960 led Dodge to exit the mid-priced segment, which was struggling due to falling sales, competition from budget brands like the Chevy Impala and Ford Galaxie, and the discontinuation of brands like Nash, Hudson, Packard Clipper, and Edsel.

Chrysler introduced two other unibody models in this struggling category: the 1960 Chrysler and DeSoto. However, DeSoto was discontinued by 1962, leaving Chrysler as the company's only mid-priced offering. The Polara 500, a more upscale version of the new mid-size Dart, was intended to replace the traditional large Dodges, at least in theory.

While the distinctively styled Dodge Dart failed to gain traction, larger cars began to regain popularity. Dodge worked quickly to improve the appeal of its mid-size model and responded even faster to dealer demands for a true "standard" car. This led to the rushed introduction of the Chrysler Custom 880 in spring 1962, essentially a 1962 Chrysler with a 1961 Polara front end and various trim pieces sourced from existing parts.

This decision was particularly ironic, as the 1962 Chrysler itself was a hastily assembled model, using 1961 Polara components for its front and rear doors, decklid, back panel, and rear bumper. The only truly new Chrysler elements were the de-finned rear quarters, which the Custom 880 also adopted.

The name '880' might have been chosen to suggest that this hastily assembled vehicle was twice the car of a top-tier Dart 440. Regardless, it provided a fast and simple solution to reintroduce the classic big Dodge, allowing planners to focus on refining the rest of the lineup. These efforts led to the launch of a new compact Dodge Dart in 1963 (replacing the 1961-1962 Lancer), a slightly larger and more conventional mid-size model for 1963-1964, and a new full-size car for 1965, which also saw the return of the Coronet name to the redesigned intermediate model.

These three images, taken on January 15, 1963, reveal that extensive bodyside chrome trim was once under consideration.

These three images, taken on January 15, 1963, reveal that extensive bodyside chrome trim was once under consideration. Another design concept for the big Dodge from around January 1963.

Another design concept for the big Dodge from around January 1963.What's in a Name: The Tale of the 'Fratzog'

Regarding names, starting in 1962, Dodge vehicles featured a sleek new emblem with a triangular design made up of three smaller triangles. Designer Bob Gale explained that it was created through an internal competition. 'We all submitted different designs,' he remembers. 'Mine came in second, and Don Wright's won, so his design was chosen.'

Wright, a former Chrysler design chief, vividly recalls the event. "An external design firm was hired to create a new logo," he recently mentioned, "but their ideas lacked an automotive feel. Bill Brownlie believed our studio could outperform them and encouraged us to brainstorm innovative concepts. My design incorporated elements from the 'Forward Look' emblem, repeated three times."

"I thought the 2-D version of the design was quite appealing," he adds, "but I was never fond of the 3-D rendition later developed by the Ornamentation Studio for the cars. Being triangular, it drew the attention of Mercedes-Benz. Their legal team and Chrysler's lawyers debated the design for years, but unlike Studebaker in 1953, we didn't have to alter it."

When Chrysler's legal team needed a name for the patent drawing, someone in the studio jokingly suggested 'fratzog,' a meaningless term that Wright still dislikes. Now you know the story behind it.

1965's New Dodge Designs

This concept from January 1963 showcases many of the design elements that would later define the 1965 big Dodges.

This concept from January 1963 showcases many of the design elements that would later define the 1965 big Dodges.1965 marked the first time in five years, since the 'P' series, that a full-size Dodge was designed from scratch. The outcome reflected the design philosophy of Elwood Engel, Chrysler's Vice-President of Styling.

Engel, who had worked under George Walker at Ford, was recruited by Chrysler President Lynn Townsend in late 1961 to take over from Virgil Exner, who was often blamed for the poor market performance of the downsized 1962 Dodge and Plymouth. Unlike Exner's finned designs of the late 1950s and his later long-hood/short-deck Valiant-style cars, Engel preferred long, horizontal lines, prominent front fenders, tapered rear ends, and balanced hood and deck lengths. His approach emphasized size and simplicity, aligning with Townsend's vision to reintegrate Chrysler into mainstream American automotive design and sales.

The 1965 full-size Dodge perfectly embodied Engel's design principles, offering an appealing yet conservative look. It shared doors with the redesigned Plymouth Fury and featured curved side glass, a design element first introduced by Exner on the 1957 Imperial.

The Polara name was used for the base models, while the more upscale Custom 880s included a six-window sedan shared with Chrysler but not with the Fury or Polara. All models showcased a new take on Dodge's 'barbell' grille, a design originally seen on the 1962 Plymouth, revived by Dodge's chief designer Bill Brownlie for the 1964 Polara, and maintained as a Dodge signature for six years.

While mid-size Dodges since 1962 had featured unusual dual headlamp arrangements, the 1965 full-size models adopted a simpler side-by-side placement at the grille's edges. The grille design, convex and with slim vertical boxes housing recessed bars, was reminiscent of the 1964 880s but more angular. Though conventional, it proved commercially successful.

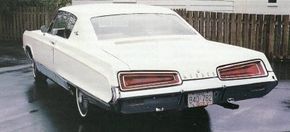

The tall, angular front fenders flowed into subtle body-side lines that narrowed toward the rear, featuring the car's standout design element: wedge-shaped 'delta' taillights. These taillights became a defining feature of Dodge throughout the 1960s.

Dodge's New Styling in 1965

A look at the stylish, wedge-shaped taillights on a 1965 Dodge Monaco.

A look at the stylish, wedge-shaped taillights on a 1965 Dodge Monaco.The 1965 Dodge redesign introduced distinctive taillights, a concept developed overnight by Diran Yazejian, who joined Chrysler in 1959 after attending the Art Center School in Los Angeles.

"I was working on the rear section of the clay model, trying to bring my sketch to life," Yazejian remembers. "The design dipped at the edges when viewed from behind, but it wasn't coming together, and the studio management was growing anxious. As my boss, John Schwarz, left for the day, he gave me until the next morning to finalize a suitable design or they'd move on to another concept."

"I decided to mirror the downward curve at the edges, forming a symmetrical wedge-shaped taillight. Collaborating with clay modelers Dick Bernock and Don Kloka, we worked overtime to rough out the design. By the next morning, when Schwarz and Brownlie arrived, we had a concept I believed would succeed. Brownlie approved, and I was given the chance to refine it, leading to its production debut." This design, with slight modifications, quickly became a signature feature across the Dodge lineup.

The initial delta taillights featured a bright horizontal bar with a circular reflector, except on the premium Monaco hardtop coupe. There, a concave rear panel was adorned with a horizontal die-cast trim piece (initially narrow but widened at Engel's request) that appeared to 'float' within red plastic, extending partially onto the taillight lenses.

The goal was to mimic the appearance of full-width lighting. While budget constraints prevented actual lighting behind the plastic, designer Frank Ruff personally modified his Monaco with small bulbs to achieve a seamless red glow.

1965 Dodge Monaco Exterior

This concept version of the 1965 Dodge Monaco reveals the fender skirt design that was ultimately discarded.

This concept version of the 1965 Dodge Monaco reveals the fender skirt design that was ultimately discarded.The 1965 Dodge Monaco shared its 121-inch wheelbase with other C-body Dodges but stood as a unique series. Initially, the mainstream 1965 models were named Polara and Polara 800, but concerns arose, leading to the retention of the Custom 880 name in the U.S. (though not in Canada). This last-minute change, approved in a Product Planning letter dated May 26, 1964, resulted in early 1965 Customs lacking series nameplates.

Marketed as the 'Limited Edition Dodge for the Man with Unlimited Taste,' the 1965 Monaco was clearly influenced by Pontiac's Grand Prix, whose impressive 1963 sales of 72,959 units served as a wake-up call for Detroit's product planners.

Dodge's naming choice, Monaco, was a nod to the famous Monaco Grand Prix racing event. Gene Weis, a former Chrysler planning executive, recalls that ad agency BBD&O found Dodge's numerical naming convention dull. The agency likely devised the Monaco's crest and possibly the name itself. 'Product Planning had no role in naming,' Weis noted.

While the Grand Prix debuted quietly in 1962, it flourished as Pontiac's flagship 'image car' in 1963, featuring a bold hardtop design with a unique roofline, concave rear window, minimal chrome, and distinctive grille, rear, and interior. The 1963 GP exuded elegance and sportiness, casting a positive influence over Pontiac's entire lineup. Dodge hoped the 1965 Monaco would achieve a similar effect.

However, the Monaco fell short of being a true Grand Prix rival, despite its slightly lower price ($3308 vs. $3426). While its rear design distinguished it from other Dodges, its grille matched the standard Polara's. Despite investing heavily in the 1965 models, Dodge planners didn't allocate funds for a unique front design to establish the Monaco's identity. (This oversight was avoided with the 1966 Charger fastback, which featured distinctive disappearing headlamps despite sharing Coronet front sheetmetal.)

Although the 1965 Dodge Monaco featured minimal exterior chrome, limited to a slender upper-body molding and a textured rocker-panel applique, it lacked the visual impact of the Grand Prix's design. Early styling records reveal that rear fender skirts were considered but wisely abandoned in favor of a sill molding.

The 1965 Dodge Monaco boasted several stylish exterior details, including fender-mounted turn signals and unique wheel covers with three-blade faux knock-off hubs. The hardtop roofline, while new, echoed the reverse-taper C-pillar design from the 1964 Polara. Optional black or white vinyl roof coverings were available at an additional cost.

1965 Dodge Monaco Interior

The Monaco was selected as the foundation for a detailed cutaway model, designed to showcase the engineering and design elements of the 1965 Dodges to auto show attendees.

The Monaco was selected as the foundation for a detailed cutaway model, designed to showcase the engineering and design elements of the 1965 Dodges to auto show attendees.Dodge allocated significant resources to interior design in 1965, especially for the Monaco. 'Our 1965 models represented a high point,' recalls former Chrysler executive Gene Weis. 'Lynn Townsend, though financially astute, acknowledged his lack of product expertise and gave Bob Anderson full control over planning. We invested heavily in every aspect of the 1965 lineup, enhancing features to outshine competitors and challenge GM.'

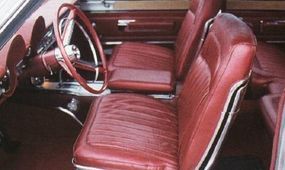

The 1965 Dodge Monaco's interior showcased this investment. A distinctive three-spoke steering wheel complemented the upscale padded dashboard, shared with other large Dodges, featuring two large circular gauges directly in front and a wide brushed-aluminum panel beneath.

The seating arrangement included bucket seats in both the front and rear, offered in three colors of pleated saddle-grain vinyl (red, black, and cordovan) or an optional combination of vinyl and 'Dawson' cloth in blue or turquoise. The rear package tray was thoughtfully designed to align with the individual seat-backs, reminiscent of the Thunderbird Sports Roadster from earlier years.

Similar to earlier Chrysler 300 models, the 1965 Dodge Monaco featured a full-length center console. This included a padded armrest with storage, a hidden rear cigar lighter, an ashtray setup, and, if selected, a front-mounted tachometer. Transmission options were the standard Torqueflite automatic or a four-speed manual, both with console-mounted shifters.

A unique touch was the use of rattan wicker accents on the Monaco's door and quarter panels, as well as on the backs of the vinyl front bucket seats (excluding cloth upholstery). The light cream wicker, with its criss-cross pattern, added a distinctive and appealing element. Above, a perforated vinyl headliner completed the look. Chrome trim was abundant, though its shine would later be subdued due to government regulations on interior reflectivity.

The standard engine for the 1965 Dodge Monaco was an updated version of Chrysler's reliable 383-cid V-8, producing 325 bhp. For those desiring more power, two optional 'wedgehead' engines were available: a reintroduced 413 with 340 bhp or the well-known 426 with 365 bhp. All Monaco engines featured four-barrel carburetors, requiring premium fuel.

A detailed second look at the 1965 Dodge Monaco's engine and interior highlights.

A detailed second look at the 1965 Dodge Monaco's engine and interior highlights.Canadian Monacos provided more engine options, beginning with a standard 225-cid Slant Six, which likely struggled under the car's 3975-pound weight. Out of the 2,068 Monacos produced in 1965 at Chrysler's Windsor, Ontario, plant, only 40 were equipped with the six-cylinder engine. Canadian models also differed in other ways. To simplify production, all senior Canadian Dodges used Plymouth Fury interiors, including dashboards. Additionally, Canadians had access to a Monaco convertible, a feature unavailable in the U.S. throughout the decade.

1965 Dodge Monaco Sales Results

The cutaway Monaco was showcased at auto shows alongside futuristic concept cars, victorious Dodge race cars, and other 1965 Dodge models.

The cutaway Monaco was showcased at auto shows alongside futuristic concept cars, victorious Dodge race cars, and other 1965 Dodge models.In the U.S., the 1965 Dodge Monaco garnered 13,096 sales, representing 10 percent of total big-Dodge production. However, this figure paled in comparison to the Grand Prix's 57,900 units sold.

While competing with the Grand Prix was challenging, the Monaco also faced internal rivalry. For instance, Plymouth's Sport Fury, featuring bucket seats, sold 44,900 hardtops and convertibles that year. Additionally, for just $192 more than a Monaco, buyers could opt for a 1965 Chrysler 300, a larger and arguably more stylish car with the added cachet of the Chrysler name.

In reality, Chrysler remained the corporation's primary mid-priced brand. Since 1961, Chrysler had marketed the Newport sedan at an aggressive price point of around $3000 or less, a strategy that contributed to DeSoto's demise and hindered Dodge's re-entry into the mid-priced market.

Former Chrysler planner Gene Weis noted that this approach aligned with the brand's 'no junior editions' policy, a jab at Buick, Olds, and Pontiac's 1961 'senior' compacts. Chrysler's leadership believed it was preferable to offer affordable full-size models rather than dilute the brand with smaller cars. As a result, the 1965 Chryslers, designed by Engel, were large, attractive, competitively priced, and set a production record for the brand.

1966 Dodge Monaco

Canadian 1966 Dodge Monaco 500 models, as pictured here, utilized Plymouth interiors.

Canadian 1966 Dodge Monaco 500 models, as pictured here, utilized Plymouth interiors.The 1966 Dodge Monaco aimed to build on the success of its predecessor. The senior Dodge lineup received a stylish update for 1966. The lower body ridge now extended over the front wheel wells, leading to sharper fenders with higher bumper ends. The grille, with its barbell design, was wider at the edges and narrower in the center, framed by a new hood and bumper. Slim vertical grille bars featured a subtle central 'blip,' creating a refined horizontal highlight, similar to the Charger. Designed by Dick Clayton and Carl Cameron, this elegant front end showcased their signature blend of clean shapes and meticulous detailing.

At the rear, new decklid and taillight designs introduced a striking arrangement of angular surfaces, crafted by Frank Ruff. The taillights retained their wedge shape but tapered inward toward the trunklid's center, where a body-colored panel displayed 'DODGE' or 'MONACO' in tall, slender lettering, designed by Cameron.

The inboard taillight sections featured two horizontal recesses. Polaras filled these with polished, vertically textured die-cast pieces, while Monacos used red lenses. Thanks to Ruff's innovations, the entire assembly lit up, creating a distinctive nighttime appearance. This design gave the senior Dodges a cohesive 'barbell' theme at both ends, a subtle yet effective detail often overlooked at the time.

In 1966, all top-tier Dodge models adopted the Monaco name. While Monaco had more appeal than Custom 880, this change weakened the unique identity of the 1965 hardtop, which was rebranded as the Monaco 500 for 1966. This decision was made hastily between April 23 and May 20, 1965.

The planned 1966 Chrysler Custom 880 was ultimately replaced by a Monaco series.

The planned 1966 Chrysler Custom 880 was ultimately replaced by a Monaco series.The Custom convertible and six-window sedan were discontinued along with the Custom name, leaving a standard Monaco lineup that included a four-window sedan, two- and four-door hardtops, and two- and three-seat wagons priced between $3,033 and $3,539. The Monaco 500 started at $3,604.

This premium model became the 1966 Dodge Monaco 500.

This premium model became the 1966 Dodge Monaco 500.Engine options were also reconfigured. The base engine for standard Monacos was a 270-bhp two-barrel 383, which was also a no-cost option for the 500. The 500 typically came with a 325-bhp four-barrel version requiring premium fuel, which was optional for other Monacos. All big Dodges could be equipped with Chrysler's largest V-8 yet, the new high-performance 440 wedgehead, though it produced 350 bhp in Dodges, 15 less than in comparable Plymouths and Chryslers.

The new standard Monacos weren't simply rebadged Customs (which would have featured Polara taillights). Instead, they were upgraded with trim and features originally intended for the 'true' Monaco, such as a polished hood windsplit, a prominent 'fratzog' hood ornament, and the striking red taillights. However, this further blurred the lines between the specialty hardtop and the rest of the Monaco lineup.

According to retired Dodge design manager Bob Gale, the Monaco 500 almost became more exclusive. Chrysler planners and designers had developed a new two-door hardtop roof for the 1966 Chrysler 300, featuring wraparound C-pillars and a smaller rear window. This design was offered to Dodge, but, as Gale recalls with disbelief, 'Bill Brownlie rejected it, believing the Dodge roof looked better!'

As a result, the big sports-luxury Dodge quickly lost its unique appeal, becoming more like an upscale Polara 500 (though without a convertible option). This shift was a consequence of replacing the Custom 880 with the more marketable Monaco name, which wasn't a bad strategy.

Chrysler had previously achieved success by replacing Saratogas with non-letter 300 models in 1962. However, the 300 name had been established for seven years and carried a strong performance legacy, whereas Monaco lacked a performance reputation and was downgraded after just one year.

1966 Dodge Monaco 500

In 1966, the Monaco 500's grille featured a more pronounced 'barbell' effect, and a bold speedline extended forward from the front wheel arches. Distinctive '500' medallions and three faux vents on the sides were key Monaco 500 design elements.

In 1966, the Monaco 500's grille featured a more pronounced 'barbell' effect, and a bold speedline extended forward from the front wheel arches. Distinctive '500' medallions and three faux vents on the sides were key Monaco 500 design elements.Regardless of names, the 1966 Dodge Monaco 500 stood out as the most attractive of the large Dodges that year. Its cleaner design included a fine-line paint stripe in four colors, replacing the upper-body molding. Circular '500' badges (shared with Polara 500s) adorned the front fenders, and sleek new rocker moldings matched the bumper. Three slim chrome rectangles with black paint on the lower fender and door added a subtle louver-like detail.

The 500 kept the unique wicker trim from the 1965 Dodge Monaco but introduced new 'shell-type' front bucket seats. Standard upholstery was all-vinyl, available in seven colors (including a new olive shade called Citron), with an optional black cloth-and-vinyl combination.

Two large dashboard pods continued to hold essential gauges, while a redesigned center console sat between the front bucket seats.

Two large dashboard pods continued to hold essential gauges, while a redesigned center console sat between the front bucket seats.The interior remained impressive, though cost-cutting measures replaced the rear bucket seats with a standard three-passenger bench, leading to a shorter, redesigned console. 'As Townsend grew more confident,' recalls former Chrysler executive Gene Weis, 'Product Planning faced intense pressure to cut costs.' Despite this, the 1966 Dodge Monaco 500 offered new options like a six-way power seat and a tilt/telescope steering wheel.

New deep-dish wheel covers debuted on the 1966 Monaco 500, shared with the Polara 500 and 1966 Charger. However, these were merely covers, unlike the Grand Prix's aluminum wheels. A unique 'sunburst' design for the Monaco 500 was planned but scrapped before production, though it later appeared on the 1974 Plymouth Satellite Sebring Sundance trim package.

The 1966 Monaco 500's taillights were an enhanced version of the delta-shaped design from the 1965 model. The base price increased by approximately $250 compared to its 1965 predecessor.

The 1966 Monaco 500's taillights were an enhanced version of the delta-shaped design from the 1965 model. The base price increased by approximately $250 compared to its 1965 predecessor.The standard 1966 Dodge Monaco achieved strong sales, with nearly 50,000 units sold for the model year—over 5,000 more than the final Custom 880s. However, this success may have come at the cost of the specialty hardtop, as U.S. production for that model dropped to 7,332 (some sources cite 10,340). Another contributing factor could have been the Chrysler 300, whose 1966 two-door hardtop was priced $21 lower than the $3,604 Monaco 500.

Dodge Design in the Mid 1960s

Most full-size Mopar two-door hardtops, including Dodge models, adopted a striking new roofline for 1967: a semi-fastback design with a wide sail panel, as seen on this Monaco.

Most full-size Mopar two-door hardtops, including Dodge models, adopted a striking new roofline for 1967: a semi-fastback design with a wide sail panel, as seen on this Monaco.While Dodge's marketing team debated names, designers faced their own challenges. During the mid-to-late 1960s, many Detroit stylists struggled with 'Pontiacitis'—a sense of inadequacy fueled by Pontiac's consistent dominance in large car design. Pontiac seemed to excel effortlessly in this category.

Ford, for instance, closely studied the 1963 Pontiac, with its vertically stacked headlights and clean, architectural lines, and created a similar car for 1965. Although it sold well, this imitation led to jokes about it being 'the box the Pontiac came in.'

The 1965 Pontiacs introduced entirely new designs, featuring sleek, flowing lines and Coke-bottle-inspired body contours that outshone both Ford and the full-size Dodge. When designing the all-new 'C' series Dodge for 1967, it appeared the Dodge team had the 1965 Pontiac catalog in mind, as its bold designs seemed to challenge, 'Top this!'

'We made a strong effort with the 1967 big-Dodge front end,' recalls former Dodge designer Jeffrey Godshall, 'which I developed with Bob Gale, then the C-body studio supervisor. While the barbell theme remained, it was less pronounced.' The design included wide, blacked-out rectangular air inlets on either side of a central panel, featuring vertical bars for Polara and an eggcrate pattern for Monaco, each divided by a bright horizontal bar.

The headlights, two five-inch round units, were housed in circular die-cast frames at the outer ends of the horizontal bars. However, this design wasn't finalized until late in the process, as Dodge experimented with vertically stacked dual headlights, similar to Pontiac and Plymouth's Fury, which had adopted them since 1965.

The central grille section planned for the 1967 Monacos and 500s is also visible in this model.

The central grille section planned for the 1967 Monacos and 500s is also visible in this model.The bumper and hood shapes of the 1967-1968 Dodge reflect the designers' uncertainty regarding the headlight configuration. The bumper's curved upper surfaces extended outward, matching the hood's leading edge and its bright trim. This design allowed for stacked headlights by simply cutting half-circles into the hood trim and bumper edges.

'I can't remember the exact reason we opted for horizontal headlights. I believe the notches required for the bumper were too challenging for Chrysler's manufacturing team,' says Godshall. Gale recalls that the horizontal layout was chosen to give the front a wider appearance. Designer Diran Yazejian attributes the change to a last-minute decision by Harry Cheesebrough, then head of product planning. This struggle highlights Dodge's challenge in competing with the 1965 Pontiac, whose vertical headlights were widely admired.

1967 Dodge Monaco

The 1967 Dodge Monaco 500 gained 85 pounds, bringing its base weight to 3,970 pounds. The design incorporated wide rocker panel trim, and standalone '500' numerals were added to the front fenders.

The 1967 Dodge Monaco 500 gained 85 pounds, bringing its base weight to 3,970 pounds. The design incorporated wide rocker panel trim, and standalone '500' numerals were added to the front fenders.Despite the designers' efforts to match Pontiac's style with the 1967 Dodge Monaco, Pontiac introduced even more innovative designs for 1967, with the Grand Prix once again leading the way.

The Grand Prix was available as both a convertible and a hardtop, featuring advanced disappearing headlights and discreet turn signals integrated into the fender tips above a bold bumper/grille. (Dodge later borrowed this idea for backup lights on the 1970 Monaco.)

In 1967, the Dodge Monaco finally received its own distinctive grille—or more accurately, a unique grille center. This design featured a rectangle divided by a horizontal bar displaying the Monaco crest, set against a finely textured eggcrate pattern, strikingly similar to the aluminum screening used on the Dodge design studio's air vents.

'Chuck Mashigan first introduced this texture for the fender vents on the 1963 Chrysler Turbine Car,' recalls designer Diran Yazejian. Dodge designers adopted this eggcrate pattern with such enthusiasm that it soon became a staple on nearly every Dodge grille, except for the Dart.

The 1967 Dodge lineup, including the Monaco, appeared significantly larger than the 1966 models—and they were. The wheelbase grew to 122 inches, largely due to requests from the California Highway Patrol. Like the princess who felt a pea under multiple mattresses, the CHP officers must have been highly perceptive to demand an extra inch in wheelbase for their Polara patrol cars. Overall length increased even more noticeably, extending over half a foot to 219.6 inches.

The bodyside design also became more striking, thanks to Dick Watson, a skilled and amiable designer who had previously worked on the 1965 big-Dodge bodyside and front end. Watson's design featured sharp, clean lines, with a broad, concave chamfer running along the upper body, widening toward the rear and curving down to align with the rear deck.

The 1967 Dodge Monaco's dashboard retained the dual-gauge theme, but the dials were now housed in square bezels that blended more seamlessly into the control panel.

The 1967 Dodge Monaco's dashboard retained the dual-gauge theme, but the dials were now housed in square bezels that blended more seamlessly into the control panel.Along the lower character line, the rear quarter panel transitioned smoothly into a horizontal skag that extended into the bumper—a design inspired by the 1965 Pontiac, which featured a similar full-length skag. On the 1967 Dodge Monaco 500, the lower body below a full-length chrome molding was covered with ribbed aluminum, another nod to the Bonneville.

The hood and trunklid were composed of expansive, flat sheetmetal surfaces. The rear quarters ended at a sharp angle. Bob Gale remembers that they were initially more upright, 'but Elwood insisted on adding more rake to the rear, declaring, 'That's more 1967!''

The Style of the 1967 Dodge Monaco

The 1967 Dodge Monaco's taillight design became even more striking. Vents beneath the rear window allowed for flow-through interior ventilation.

The 1967 Dodge Monaco's taillight design became even more striking. Vents beneath the rear window allowed for flow-through interior ventilation.The 1967 Dodge Monaco's design was meticulously crafted and visually striking. The delta taillights evolved into large, flaring trapezoids above a notched bumper, representing the boldest version of the delta concept yet. The area between the taillights' inner and outer bezels was finished in sintered silver metallic for Polaras and taillight red for Monacos, creating a bold and unmistakably Dodge appearance.

The upper sections of the Dodge Monacos maintained sharp, rectangular lines, except for the new 1967 semi-fastback two-door hardtops. This design, created by Ed Westcott of the Chrysler Studio, featured a large triangular sail panel that seamlessly blended into the rear quarters. Dodge designers had long sought to integrate the C-pillar and quarter panel effectively, though the older design with the pillar atop the quarter might have sufficed.

The era's popular vinyl roofs required bright trim moldings that disrupted the otherwise smooth surfaces, fragmenting their visual flow. (Pontiac designers faced the same issue.) The new hardtops also included flow-through ventilation, marked by a painted air-exit grille on the upper deck panel just below the rear window.

Inside, the 1967 Dodge Monaco 500 retained its signature wicker accents in familiar locations, and a reclining passenger seat became an optional feature. The dashboard evolved from the 1965-1966 design, with the circular gauge panels replaced by rectangular ones. New wheel covers, designed by Jeffrey Godshall, featured a black outer ring with bright radial louvers surrounding a raised cone and a fratzog emblem at the center.

Engine options for the 1967 Dodge Monacos remained largely unchanged, except for the introduction of the Magnum 440. This 'A-134' engine, with its enlarged intake and exhaust ports, longer-duration camshaft, specialized valve springs, four-barrel carburetors, low-restriction exhaust manifolds, and a larger dual exhaust system, produced an impressive 375 horsepower. It was standard on the new Coronet R/T and optional for Chargers, Polaras, and Monacos.

Despite bolder styling and increased dimensions, big-Dodge sales dropped in 1967. The Monaco 500 saw only 5,237 units sold, while the Grand Prix achieved nearly 43,000 sales, bolstered by its striking design and new convertible option.

1968 Dodge Monaco

In 1968, the Dodge Monaco underwent a subtle cosmetic update. The taillights were redesigned to span the car's full width, and the front featured a streamlined three-section grille.

In 1968, the Dodge Monaco underwent a subtle cosmetic update. The taillights were redesigned to span the car's full width, and the front featured a streamlined three-section grille.As expected, 1968 brought a facelift for the big-Dodge lineup, with new federally mandated side marker lights serving as a clear identifier. The 1968 Dodge Monaco followed suit, with revised side trim and hardtop sedans receiving tapered C-pillars and smaller rear windows, though the visual changes hardly justified the production costs.

The front end was updated with a redesigned three-section grille by Bob Gale, featuring recessed, full-width inserts and prominent twin vertical bars that aligned with the existing hood and bumper design. Polaras used a horizontal-bar pattern, while Monacos kept the eggcrate texture with a central crest.

At the rear, all 'D' series models shared a new bumper and decklid, along with full-width taillights that flared outward into subtle wedges. Polaras concealed their taillights behind closely spaced vertical chrome ribs, while Monacos reintroduced wall-to-wall taillights divided by a thin 'cross-hair' bar. A vertical central backup light, aligned with the decklid windsplit, marked the first time Chrysler used this design since the 1958 Plymouth. The Dodges finally achieved a Pontiac-style 'split grille,' albeit at the rear.

The Monaco 500 remained a standalone series for 1968, but its ribbed lower side trim was now used on other Monacos, albeit in a narrower version. Cornering lamps integrated into the lower front fenders became a standard feature for the 500, though the interior wicker trim was removed. Dashboards were updated again, while engine options stayed the same, with a slight power increase for the 383.

Despite minimal changes, senior Dodge sales rebounded in 1968—except for the Monaco 500, which dropped to 4,568 units, even though the comparable Chrysler 300 now had a higher starting price ($4,010 vs. $3,869). Many potential 500 buyers likely opted for the new 1968 Charger instead, a standout model with its elongated front, 'double-diamond' body lines, and unique 'tunnelback' roof.

The Dodge Monaco's 1969 Demise

By 1969, the Dodge Monaco had officially come to an end. The big Dodges adopted the 'fuselage look' from the Charger for 1969, but the Monaco 500 was downgraded to an optional package, indicated only by subtle front-fender badges.

By this time, most dealers were focused on selling economy Darts and performance-oriented Coronets and Chargers, making big cars a secondary concern. Sporty full-size models were also losing popularity across Detroit. Even the renowned Grand Prix was reimagined for 1969, becoming a uniquely styled mid-size hardtop on a 118-inch wheelbase—essentially a 'Ford Thunderbird Lite.'

Explore the range of engine options offered for the Dodge Monaco and Monaco 500 over the years in the chart below:

From the start, the specialty hardtop Dodge Monaco was hindered by insufficient funding and overshadowed by its more utilitarian counterparts. It never fulfilled the ambitious vision its planners had hoped for. It's unfortunate, as the name itself deserved a legacy far greater than being remembered as a mere Grand Prix imitator.