San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge welcomed the public on May 27, 1937. Explore some intriguing and lesser-known details about this world-famous architectural wonder.

1. THE IDEA WAS FIRST SUGGESTED IN 1872.

Charles Crocker, a railroad magnate, proposed the concept of a bridge across the Golden Gate Strait to the Marin County Board of Supervisors in 1872, just three years after the transcontinental railroad was completed. Named Chrysopylae (Greek for “golden gate”) by Captain John Fremont in 1846, the strait posed significant challenges due to its width of over a mile and strong currents ranging from 4.5 to 7.5 knots. The idea gained serious traction only in 1919, when Michael O’Shaughnessy, San Francisco’s city engineer, conducted a feasibility study. The initial cost estimate for the bridge was a staggering $100 million.

2. THE INITIAL DESIGN WAS COMPLETELY UNLIKE THE FINAL VERSION.

In 1920, O’Shaughnessy reached out to three renowned engineers—Joseph B. Strauss, Francis C. McMath, and Gustav Lindenthal—to explore building a bridge across the strait. Strauss proposed a unique symmetrical cantilever-suspension hybrid design, which he had personally developed and patented. Estimates for the project ranged between $17 million and $27 million, according to Strauss.

The bridge commission kept the design under wraps for a year, even as Strauss campaigned to garner public support. When the design was finally unveiled, it faced significant backlash. Critics in the local media labeled it unattractive, with one journalist describing it as “a clumsy, inelegant structure that awkwardly combined a bulky tinker toy framework at each end with a short suspension span, appearing to struggle across the Golden Gate” [PDF].

Ultimately, Strauss discarded his original design in favor of a more traditional suspension bridge (details to follow).

3. THE WAR DEPARTMENT HAD TO GIVE ITS APPROVAL.

Since the War Department owned the land on both sides of the strait, their approval was essential for the bridge's construction. A provisional permit was issued on December 24, 1924, followed by the final authorization on August 11, 1930.

4. THE BRIDGE FACED SIGNIFICANT OPPOSITION.

“In 1930, the Golden Gate Bridge was met with 2300 lawsuits,” transportation expert Rod Diridon explained to NBC Bay Area. Among the opponents was the Southern Pacific Railroad, which held a 51 percent stake in the ferry service operating between San Francisco and Marin County. Environmentalists like Ansel Adams and the Sierra Club also opposed the project, fearing it would disrupt the strait’s natural beauty.

As noted by the Federal Highway Administration, securing approval for the bridge required “multiple favorable court decisions, a legislative act from the State, two Federal hearings, consent from the U.S. Department of War (which initially worried about navigation interference), assurances of local hiring preferences, and a widespread boycott of the Southern Pacific Railroad’s ferry service.”

5. STRAUSS REMOVED A CRUCIAL DESIGN TEAM MEMBER BEFORE CONSTRUCTION BEGAN.

In 1922, Strauss recruited Charles A. Ellis, the author of Essentials in the Theory of Framed Structures, to lead the bridge’s design and oversee its construction. By 1925, Ellis and Strauss had enlisted Harvard’s George F. Swain and Leon S. Moisseff, the designer of New York’s Manhattan Bridge, as consultants. By late 1929, the team had transitioned from Strauss’s original concept to a suspension bridge designed by Moisseff. Purdue University notes that Ellis was responsible for “conducting thousands of calculations, drafting specifications for ten construction contracts, and supervising site testing, including the challenging task of securing stable foundations on the Marin shore.” For three years, Ellis worked tirelessly, even spending months collaborating with Moisseff on intricate calculations.

In November 1931, Strauss—who, as PBS reports, “lacked a deep understanding of the engineering complexities” and grew impatient with the delays—ordered Ellis to take a break. Just three days before Ellis was set to return, Strauss sent a letter instructing him to take an indefinite, unpaid leave and hand over all responsibilities to his assistant.

Unable to secure another position, Ellis continued working on the Golden Gate Bridge’s calculations unpaid, dedicating up to 70 hours a week. (He submitted his final report in 1934 [PDF], which Strauss and Moisseff disregarded.) Ellis later became a professor at Purdue, and when the bridge opened in 1937, he received no recognition for his contributions, despite claiming to have designed “every nut and bolt on the darn thing.” His pivotal role in the project only came to light after his death in 1949.

6. CONSTRUCTION OFFICIALLY COMMENCED IN 1933.

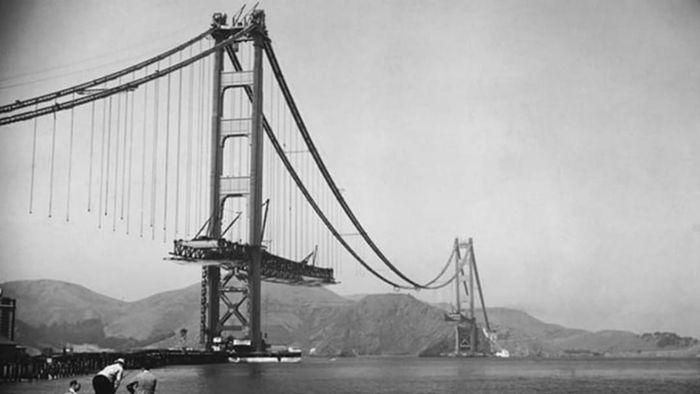

Library of Congress

Library of CongressFollowing years of delays and fundraising efforts, Strauss and his team officially began construction on January 5, 1933. The groundbreaking ceremony was a grand affair: As detailed in the official program [PDF], a parade led to Crissy Field, where opening speeches were delivered, a message from President Herbert Hoover was read, and a 21-gun salute was fired. A symbolic bridge was even painted in the sky. The event also featured a pageant where engineering students displayed an 80-foot model of the bridge, complete with carrier pigeons meant to spread news of the groundbreaking across California. (One newspaper reported that the pigeons were so startled by the crowd that boys had to use sticks to coax them out of the model.) The ceremony concluded with San Francisco Mayor Angelo Rossi and bridge Board President William P. Filmer breaking ground with a golden spade, followed by a closing prayer. Over 100,000 people attended the festivities.

7. THE CABLES WERE PRODUCED BY THE BROOKLYN BRIDGE’S MANUFACTURER.

The bridge in 1936. | General Photographic Agency/Getty Images

The bridge in 1936. | General Photographic Agency/Getty ImagesIn a suspension bridge, every component is crucial, but the cables are especially vital: They stretch horizontally between two massive concrete anchorages on either side of the bridge, with vertical suspender ropes connecting the main cables to the roadway. When vehicles exert pressure on the deck, the suspender ropes transfer this load to the main cables, which then channel it to the towers, bearing the majority of the weight.

For the Golden Gate Bridge, Strauss required cables robust enough to endure the bridge’s structure and flex 27 feet sideways in the strait’s powerful winds. These cables had to be manufactured on-site. He enlisted Roebling's Sons Co., the same firm that crafted the Brooklyn Bridge’s cables 52 years prior. For this project, they developed parallel wire construction. The spinning process began in 1935; as PBS explains:

"To create the cables, 80,000 miles of steel wire, each less than 0.196 inches thick, were wound into 1,600-pound spools and attached to the bridge’s anchorages. A strand shoe secured the 'dead wire,' while a spinning wheel, or sheave, pulled a 'live wire' across the bridge. Once it reached the other side, the live wire was fastened to the strand shoe, and the wheel returned with another loop to repeat the process. … Wire by wire, the cables were spun from tower to tower and anchorage to anchorage. The task was meticulous, requiring precise sequencing to ensure the cables could withstand the necessary wind pressure."

To complete the spinning within 14 months and on budget, Roebling's introduced a split-tram system capable of spinning six wires simultaneously. This innovation allowed them to spin 1,000 miles of wire in a single eight-hour shift. Their efficiency enabled the cables to be finished eight months early. (The company’s museum now houses an 80-foot model of the bridge.)

The bridge’s two main cables each measure 7,659 feet in length, over three feet in diameter, and consist of 27,572 parallel wires. These are the largest cables ever spun, with a combined length sufficient to encircle the Earth at the equator more than three times.

8. SAFETY WAS THE TOP PRIORITY ...

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesIn the 1930s, construction workers faced significant risks, with one fatality expected for every million dollars spent on major projects. Strauss was determined to defy these odds, investing heavily in safety measures. Strict rules were enforced: “Strauss was relentless,” recalled Pete Williamson, a bridge worker. “Any careless behavior, like standing on one foot, would get you fired.” Workers were required to wear anti-glare goggles, apply protective creams to shield their skin from harsh winds, and follow special diets to prevent dizziness. Strauss also commissioned the E.D. Bullard Company to design custom hard hats, which were mandatory at all times. In 1936, he installed a $130,000 safety net beneath the bridge, similar to those used in circus acts. Manufactured by the J.L. Stuart Company, the net extended 10 feet wider and 15 feet longer than the bridge, boosting both construction speed and worker confidence. It saved 19 lives, earning those men the nickname Halfway to Hell Club.

9. … BUT ACCIDENTS STILL OCCURRED.

For the majority of the construction period, Strauss’s site had no fatalities. However, just months before the bridge’s completion, tragedy struck when a worker was killed by a falling derrick. Weeks later, scaffolding collapsed, sending 12 workers into the safety net. The net tore, and the scaffolding fell 220 feet into the water, resulting in 10 deaths. One survivor, 26-year-old Slim Lambert, recalled, "As I fell, a piece of lumber hit my head, nearly knocking me out. The freezing water revived me." Despite a broken shoulder, ribs, and neck vertebrae, he managed to swim to safety.

10. AN EARTHQUAKE STRUCK DURING CONSTRUCTION.

Albert "Frenchy" Gales, a construction worker, was atop the south tower during the June 1935 earthquake. He later described the experience: “The tower swayed 16 feet in each direction. There were 12 or 13 of us up there with no way down—the elevator wasn’t working. As it swayed toward the ocean, we’d say, ‘here we go!’ Then it swung back toward the Bay. Some guys were lying on the deck, vomiting. I thought if we fell, the iron would hit the water first.”

11. EACH 746-FOOT TOWER CONTAINS APPROXIMATELY 600,000 RIVETS.

When the original rivets corrode, they are replaced with galvanized high-strength bolts.

12. THE BRIDGE IS PAINTED “INTERNATIONAL ORANGE.”

Initial color proposals for the bridge included carbon gray, aluminum, or black, with the U.S. Navy advocating for black with yellow stripes to enhance visibility. However, Irving Morrow, the consulting architect (who also designed the bridge’s Art Deco style), rejected these options. He found black unappealing and diminishing to the bridge’s grandeur, while aluminum made the towers appear insignificant.

Ultimately, Morrow drew inspiration from the red primer coating the steel beams manufactured in eastern factories, choosing International Orange. This color not only harmonized with the natural surroundings but also ensured the bridge stood out against the sea and sky. “International Orange creates a striking and unique visual impact in the field of engineering,” Morrow remarked. Additionally, the color offers excellent visibility in foggy conditions.

The CMYK breakdown for International Orange is Cyan: 0 percent, Magenta: 69 percent, Yellow: 100 percent, Black: 6 percent. Sherwin-Williams currently supplies the paint used for the bridge.

13. ITS OPENING WAS MARKED BY A WEEK-LONG CELEBRATION.

The bridge’s construction spanned just over four years, with the project costing a total of $35 million. Upon its completion, San Francisco celebrated with a week-long Golden Gate Bridge Fiesta from May 27 to June 2. Strauss, who was both an engineer and a poet, recited a poem he wrote for the occasion titled “The Mighty Task is Done,” which begins:

At last the mighty task is done; Resplendent in the western sun The Bridge looms mountain high; Its titan piers grip ocean floor, Its great steel arms link shore with shore, Its towers pierce the sky.

The first day of the celebration, dubbed “Pedestrian Day,” saw 15,000 people per hour passing through the turnstiles, each paying 25 cents to cross. Some crossed on stilts, roller skates, or unicycles. Vendors along the bridge sold an estimated 50,000 hot dogs. At noon on May 28, FDR pressed a telegraph key in the White House, announcing the bridge’s opening globally. At 3 p.m., a fleet of 42 Navy ships sailed beneath the bridge, and the day concluded with a fireworks display at 10 p.m. During the festivities, a Fiesta Queen of the Golden Gate Bridge was crowned, though accounts vary on the winner.

14. THE BRIDGE IS INCREDIBLY HEAVY.

When the bridge opened in 1937, its total weight, including anchorages and approaches, was 894,500 tons. A re-decking project in 1986 reduced the weight to 887,000 tons.

15. THE BRIDGE HAS BEEN SHUT DOWN THREE TIMES DUE TO WEATHER.

The longest weather-related closure in the Golden Gate Bridge’s history happened on December 3, 1983, when winds hit 75 mph, forcing the roadway to close for three hours and 27 minutes. Other full closures have occurred for anniversaries and construction, as well as brief shutdowns for visits by dignitaries like Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Charles de Gaulle.

16. IT INFLUENCES THE FORMATION OF FOG.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressAs stated on the bridge’s website, “The Bridge plays a role in guiding the fog as it rises and cascades around the structure. At times, high pressure compresses it close to the surface.”

17. IT HELD THE TITLE OF THE WORLD’S LONGEST SUSPENSION BRIDGE UNTIL 1964.

That record now belongs to Japan’s Akashi-Kaikyo Bridge, which spans 6500 feet. However, the Golden Gate Bridge remains one of the most photographed bridges globally.

18. THE ONE BILLIONTH DRIVER CROSSED ON FEBRUARY 22, 1985.

Dr. Arthur Molinari, a dentist, was the fortunate driver. He received a hardhat and a case of champagne as a reward.

19. THE 50TH ANNIVERSARY TURNED INTO A CHAOTIC EVENT.

Officials anticipated 50,000 attendees for the Golden Gate Bridge’s 50th anniversary on May 24, 1987. However, 800,000 people arrived, leading to a situation described in a subsequent report [PDF] as chaotic:

The Golden Gate Bridge visibly reacted to the massive crowd, with the roadway deflecting nearly 10 feet at its midpoint. ... The 17 mph winds across San Francisco Bay worsened the situation. Suspension bridges are sensitive to wind, and as the bridge swayed and flattened under the weight, panic ensued. Crowd density caused nausea and claustrophobia, making it nearly impossible to direct people off the bridge.

“The bridge completely flattened—its arch vanished,” recalled Gary Giacomini, president of the Bridge District Board. “It bore the heaviest load in its 50-year history. The center cables were taut as harp strings, while those near the towers flapped in the wind … I thought, ‘This isn’t good!’”

Despite the alarming scene, there was no cause for concern. The report noted the bridge deck was designed to handle 15 feet of vertical movement and 27 feet of lateral sway. Charles Seim, a former supervising bridge engineer, stated, “We exceeded design loads, but I wasn’t worried. Even at the maximum load of 5700 pounds per foot, cable stress was only 40 percent of their yield strength, leaving a large safety margin.”

20. IT’S A HOLLYWOOD ICON.

The bridge has starred in numerous films, such as The Maltese Falcon (1941), Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978), Interview with the Vampire (1994), and The Rock (1998). Filmmakers often depict its destruction in movies. It also graced the cover of Rolling Stone on February 26, 1976.