Since the earliest attempts to chart the world, the field of cartography has evolved dramatically, driven by technological and intellectual progress. Each map, however, reflects a unique perspective influenced by the era and culture of its creation. From an ancient Roman travel guide to a depiction of poverty in Victorian London, these 20 maps have reshaped how humanity perceives the world.

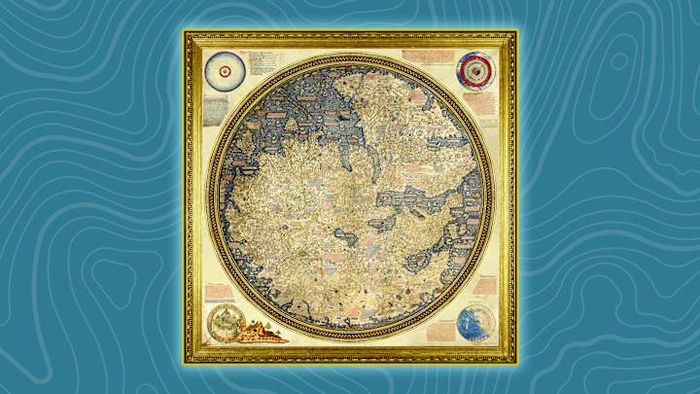

Babylonian Map of the World

The Babylonian Map of the World. | Fine Art/GettyImages

The Babylonian Map of the World. | Fine Art/GettyImagesDating back to the 6th century BCE, the oldest known world map is a small clay tablet, measuring 4.8 by 3.2 inches. This artifact presents the world through the Babylonians’ perspective, featuring two concentric circles surrounded by triangular shapes, some of which are missing due to damage. The design resembles a star, offering a glimpse into ancient cartography.

The Euphrates River runs through the central circle, with Babylon positioned in the northern part. Other ancient cities, such as Susa (accurately placed in the south) and Habban (inaccurately in the northwest), are also represented. The area between the circles is labeled as the “bitter river” (the sea), while the triangles are believed to depict either mythological locations or real places beyond the knowledge of the Mesopotamians.

Ptolemy’s Geographia

Claudius Ptolemy, an Alexandrian scholar, compiled an atlas around 150 CE, consolidating the geographic knowledge of the 2nd-century Greco-Roman world. Using latitude and longitude grid lines, Ptolemy mapped approximately 8000 locations, creating a foundational work in the history of geography.

Despite the inaccuracies in Ptolemy’s calculations, which caused distortions in measurements, he pioneered the use of mathematics in mapmaking. Some features of his world map, such as the precise depiction of the Nile River, are remarkably accurate for his era. However, his assumption that the Indian Ocean was enclosed by a landmass linking Africa and Asia proved incorrect.

No original versions of Ptolemy’s map exist today. His Geographia was translated into Arabic by al-Khwārizmīin during the 9th century, then vanished for centuries. It was later rediscovered by Byzantine scholars in the 14th century and gained widespread popularity in Europe after Jacopo d’Angelo’s Latin translation in 1406.

Tabula Peutingeriana

The Roman Empire was a hub of innovation. As Reg (John Cleese) famously quipped in Monty Python’s Life of Brian (1979), the Romans excelled in “sanitation, medicine, education, wine, public order, irrigation,” and, of course, their road network, which “goes without saying!”

Given the extensive Roman road system—known as the cursus publicus—it’s no wonder they created a map. The Tabula Peutingeriana is unusually elongated, stretching 22 feet in length but just a foot in width. This unique shape sacrifices geographic accuracy, compressing north-south distances while elongating east-west ones. Nevertheless, the map served as a practical guide to the Roman Empire and beyond, including parts of India and China. It details 555 cities and 3500 landmarks, from temples to rivers.

The sole surviving copy of the Tabula Peutingeriana dates back to 1265, though its original version was crafted in the 4th century. Only 11 of the 12 sheets from the 1265 map remain, with the missing sheet believed to have illustrated Britain, the Iberian Peninsula, and Morocco.

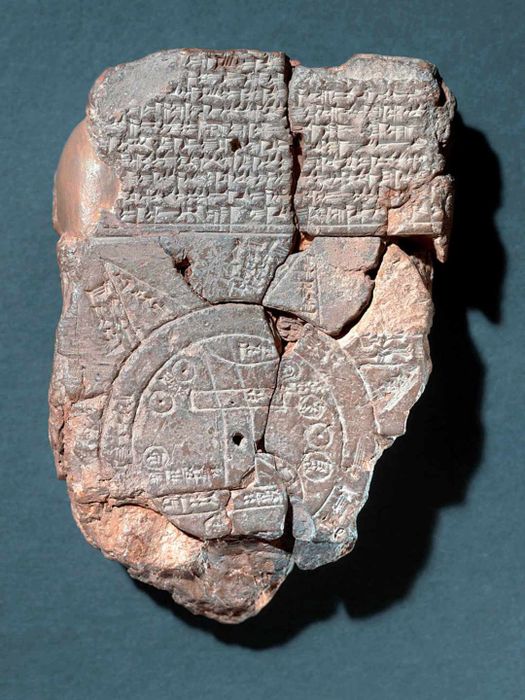

Yu Ji Tu

A rubbing of the Yu Ji Tu. | Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

A rubbing of the Yu Ji Tu. | Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainWhile many mapmakers still blended mythology with geography, an anonymous Chinese cartographer achieved remarkable precision. The Yu Ji Tu, or Map of the Tracks of Yu, depicts China’s coastline and rivers on a stone slab. Although the stele is from 1137, the map’s content may be older. It features the Yellow and Yangtze Rivers, their tributaries, and several lakes, using a detailed grid of 5110 squares, each representing 100 li (31 miles). Carved into stone, the map allowed users to create rubbings for navigation.

Tabula Rogeriana

When Abu Abdullah Muhammad al-Idrisi al-Qurtubi al-Hasani as-Sabti, commonly known as al-Idrisi, was commissioned by Norman King Roger II of Sicily to create an atlas, he had access to a wealth of knowledge. Al-Idrisi incorporated diverse cultural influences, drawing from Ptolemy’s Geographia, Arabic texts, travelers’ accounts, and his personal observations to craft his maps.

Al-Idrisi finished his Tabula Rogeriana in 1154, after 15 years of meticulous work. His world map is uniquely oriented with south at the top, a reflection of Islamic cartographic tradition that prioritized Mecca’s prominence. Remarkably, he calculated the Earth’s circumference with 10 percent accuracy, and his map remained the most precise representation of the world for three centuries.

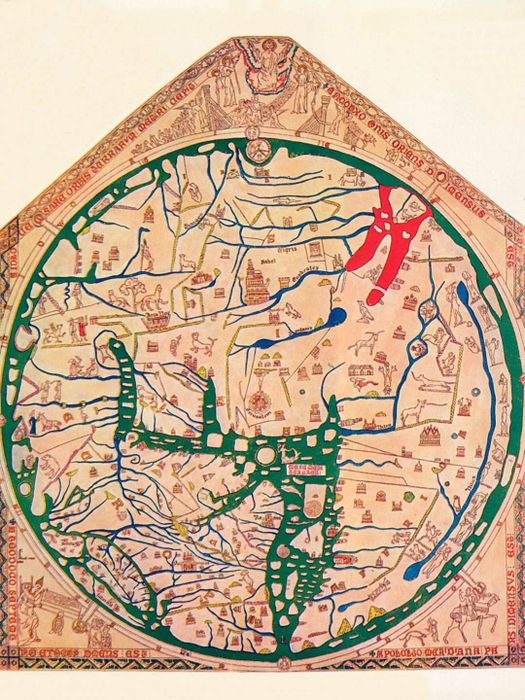

Hereford Mappa Mundi

The Hereford Mappa Mundi. | Print Collector/GettyImages

The Hereford Mappa Mundi. | Print Collector/GettyImagesBelieved to have been crafted around the early 14th century, the Hereford Mappa Mundi stands as the largest extant medieval map, spanning 5.2 by 4.4 feet. It reflects the era’s religious significance, serving not as a navigational tool but as a theological depiction of the world. The map places east at the top, aligning with the Christian belief that the Garden of Eden lay in the east, deserving the highest position, while Jerusalem occupies the central focus. Alongside real cities, it features biblical and mythological sites, such as the Minotaur’s Labyrinth and Noah’s Ark, as well as fantastical creatures like Cynocephali (dog-headed humans) and a unicorn, scattered throughout.

Kangnido

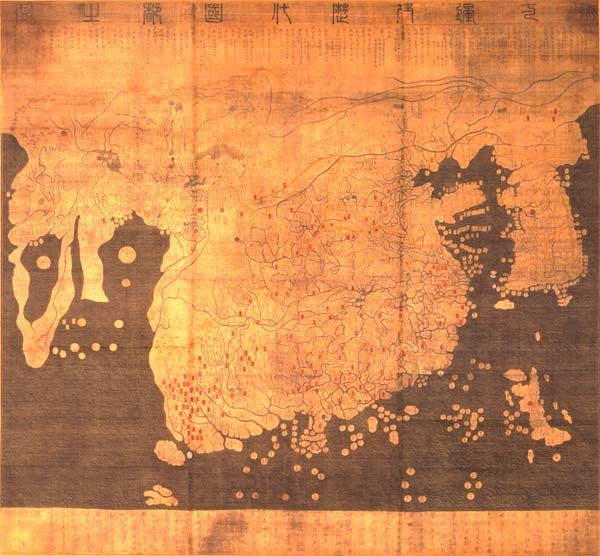

The Kangnido map. | Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

The Kangnido map. | Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainKorea’s Honil Gangni Yeokdae Gukdo Ji Do, commonly known as Kangnido, is an East Asian map that contrasts sharply with the Jerusalem-centric maps of Europe, bearing a closer resemblance to modern cartography. Created by Kwon Kun and Yi Hoe in 1402, it is Korea’s oldest surviving map and, alongside China’s Da Ming Hunyi Tu, one of the earliest maps from East Asia.

The Kangnido is notable for being among the first maps to suggest that the southern tip of Africa could be circumnavigated. It provides more accurate depictions of Korea and Japan compared to its Chinese counterparts. However, China and Korea are depicted as disproportionately large, reflecting their status as economic and political powerhouses during that period.

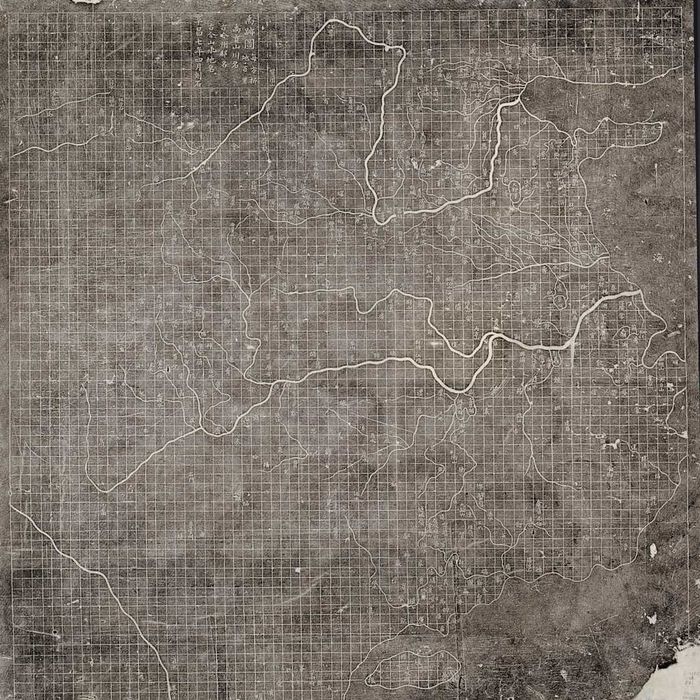

The Fra Mauro Map

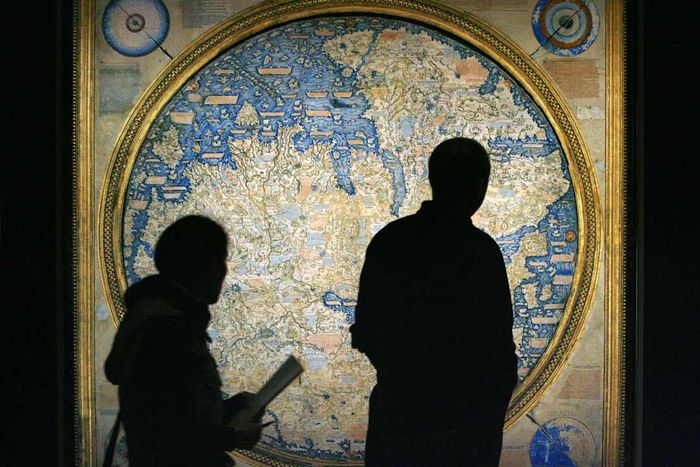

A reproduction of the Fra Mauro map displayed at a museum. | MICHAEL KAPPELER/GettyImages

A reproduction of the Fra Mauro map displayed at a museum. | MICHAEL KAPPELER/GettyImagesFra Mauro, a Venetian monk, was among the first European cartographers to largely abandon religious and mythical influences in favor of a more scientific methodology. Commissioned by King Alfonso of Portugal, Mauro employed a crowdsourcing strategy to collect data for his map. As Venice was a bustling port, he gathered insights from numerous travelers and relied on extensive written sources, including Ptolemy’s Geographia and the travel accounts of Marco Polo.

Although Mauro’s map featured tales of mythical creatures and places, such as sea monsters and a gold-producing lake, he also included annotations expressing doubt about their existence. Completed in 1459, his map was the most precise European depiction of Africa (showing its southern tip as circumnavigable) and Japan (accurately portrayed as an island) at the time.

The Waldseemüller Map

When Christopher Columbus arrived in the Americas in 1492, he mistakenly believed he had reached islands near Asia. This misconception was corrected in the early 16th century by Italian explorer Amerigo Vespucci, who identified the land as a distinct continent. This revelation necessitated a new world map, as existing ones only featured Europe, Asia, and Africa. In 1507, German cartographer Martin Waldseemüller created a map that included and named the new continent “America” in Vespucci’s honor.

The Waldseemüller Map is often referred to as “America’s birth certificate.” Of the 1,000 copies originally printed, only one survives today. In 2003, the Library of Congress acquired it for $10 million.

Diogo Ribeiro’s World Map

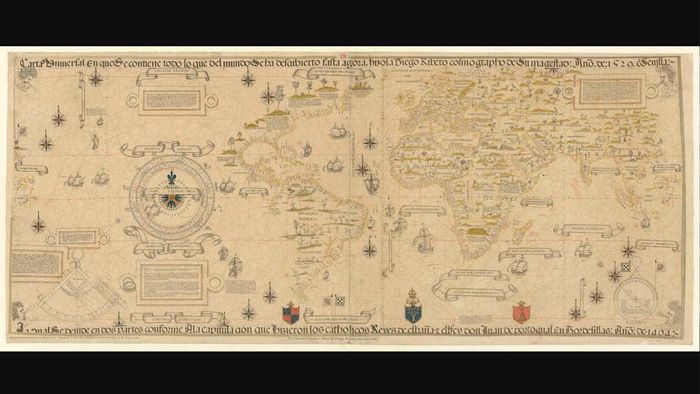

Diogo Ribeiro may have fudged some geography. | Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

Diogo Ribeiro may have fudged some geography. | Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainIn the 1520s, Portuguese cartographer Diogo Ribeiro was commissioned by King Charles V of Spain to create a world map. While Ribeiro aimed for precision, one specific area was inaccurately depicted—possibly due to political motives.

During the late 15th and early 16th centuries, Spain and Portugal vied for dominance in the spice trade. The 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas divided the Atlantic, granting the west to Spain and the east to Portugal. When Ferdinand Magellan discovered the Moluccas islands—now part of Indonesia—they technically belonged to Portugal. However, Ribeiro placed them slightly within Spain’s territory on his map. Whether this was an honest error or an attempt to appease his Spanish employer remains unclear.

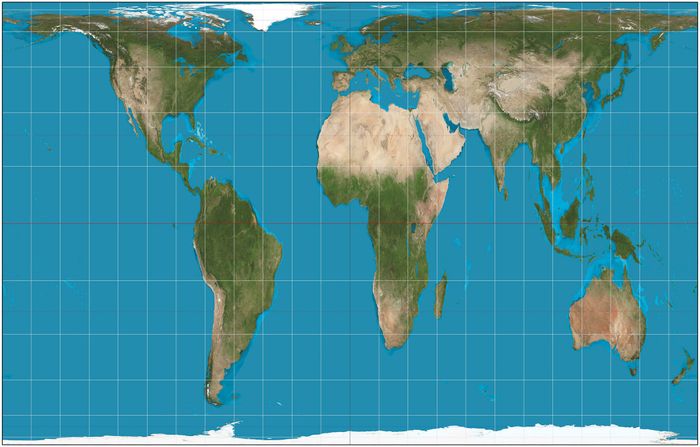

The Mercator Projection

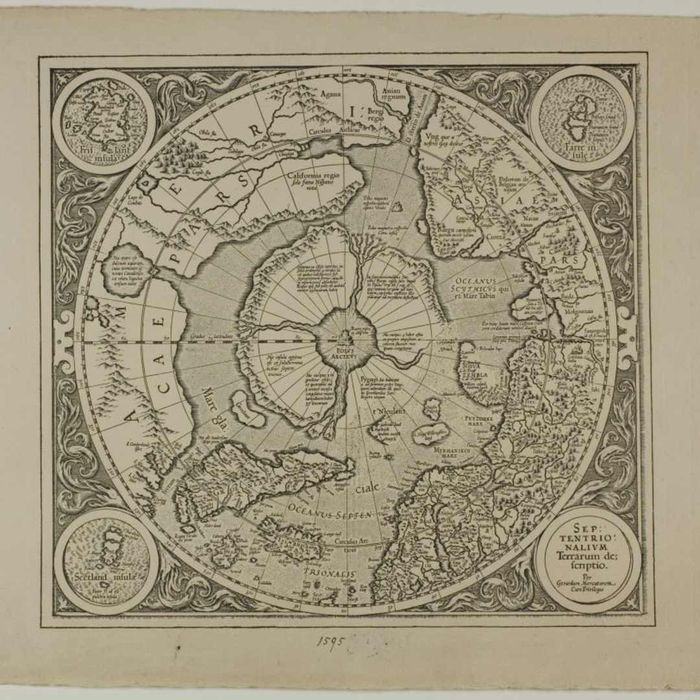

The Mercator Projection. | Heritage Images/GettyImages

The Mercator Projection. | Heritage Images/GettyImagesRepresenting a 3D globe on a 2D surface has always challenged cartographers, but in 1569, Flemish mapmaker Gerardus Mercator devised a solution ideal for sailors. His projection features equally spaced vertical longitude lines, while horizontal latitude lines widen as they move away from the equator. This design mimics Earth’s curvature, enabling navigators to chart straight courses using a single compass bearing.

By the 18th century, the Mercator projection became the go-to navigational map, and by the 19th century, it dominated atlases. Its prominence waned only recently due to its distortions—Google Maps used it until switching to a globe view in 2018. The widening latitude lines exaggerate landmass sizes farther from the equator. For example, Greenland appears similar in size to Africa, despite being 14 times smaller.

The Codex Quetzalecatzin

The colonization of the Americas not only altered European maps but also influenced indigenous cartography. The Codex Quetzalecatzin, a rare Mesoamerican manuscript from the late 16th century, serves as a land claim document for the descendants of Lord-11 Quetzalecatzin, depicted in the illustrations, asserting their rights to territories spanning from Mexico City to Puebla.

The Codex Quetzalecatzin illustrates the blending of indigenous Aztec and Spanish cultures. While it retains traditional Aztec elements like hieroglyphics and geographic symbols, it also incorporates Spanish influences, such as the Latin alphabet, Spanish place names, and Christianized names for indigenous leaders.

Atlas Maior

Flemish geographer Abraham Ortelius is recognized for producing the first modern atlas, Theatrum orbis terrarium, in 1570. While Ortelius’s work was popular, it wasn’t until the 17th century that atlases became fully commercialized, thanks to Willem Blaeu and his sons Joan and Cornelius. Their editions, culminating in the Atlas Maior, were designed to maximize sales rather than cartographic accuracy. The Atlas Maior was the most expensive book of its time, serving as a luxurious status symbol for the wealthy.

The Cassini Map of France

Details from the Cassini Map. | Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

Details from the Cassini Map. | Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainTriangulation, though less common today, was groundbreaking when used for the Cassini Map of France. In 1747, King Louis XV commissioned César-François Cassini to produce a detailed map of France to improve tax collection. Nine years later, Cassini presented the first sheet, created using the triangulation method developed by his grandfather, Giovanni Domenico Cassini. However, Louis withdrew funding, forcing Cassini to seek private sponsors. With the help of provincial leaders, surveyors, locals, and illustrators, he completed the map, which spanned 182 sheets and covered 36 square feet.

When the French Revolution began in 1789, the nearly finished map was seized from Cassini’s son, Jean-Dominique, as part of nationalization efforts. Jean-Dominique expressed his frustration, asking, “Can a painter be deprived of his canvas before adding the final touches?”

Even incomplete, the map held immense significance. It was not only the most precise map of France at the time but also inspired Britain’s state-funded Ordnance Survey triangulation maps.

John Snow’s Cholera Outbreak Map

In August 1854, London’s Soho district was struck by a cholera outbreak. Within a week, 10 percent of the population had succumbed to the disease. While most medical professionals believed cholera was airborne, physician John Snow argued it was waterborne. To support his theory, he created a map plotting the deaths, revealing a cluster around the Broad Street water pump. Investigations later confirmed the pump was contaminated by sewage.

Snow’s map was groundbreaking in several ways: it confirmed cholera as a waterborne illness, spurred improvements in London’s sanitation, and showcased the power of combining cartography with epidemiology.

Charles Booth’s Poverty Map

Another transformative Victorian-era map of London is Charles Booth’s 1889 Poverty Map. Sensationalist media often exaggerated the extent of urban poverty, prompting businessman Charles Booth to challenge these claims with factual evidence. A study by Henry Hyndman, leader of the Social Democratic Federation, had asserted in 1885 that 25 percent of Londoners lived in poverty. Booth believed this was an overstatement and embarked on his own investigation.

Using data from School Board visitors, who monitored children’s attendance, Booth developed a color-coded map illustrating poverty levels across London. His findings revealed that the issue was worse than reported, with nearly a third of the population living in poverty.

Booth expanded his research to explore how poverty intersected with religion, education, and politics. He published his findings and maps in the series Life and Labour of the People in London, completed in 1903. Additionally, he advocated for social reforms, influencing policies like pensions and free school meals, and became a key figure in these initiatives.

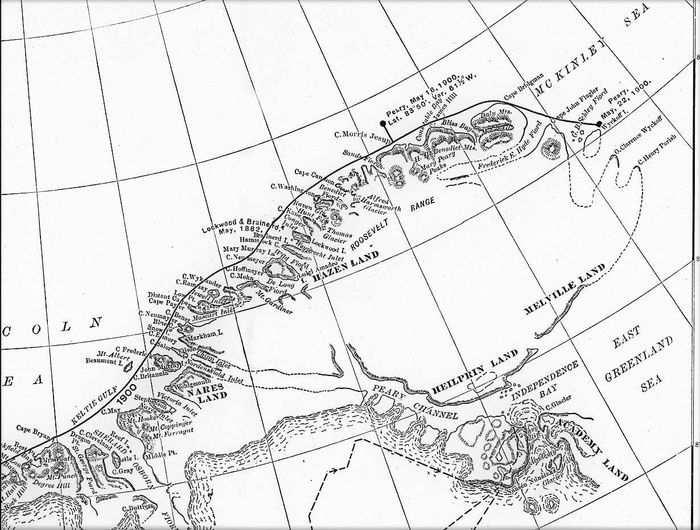

Robert Peary’s Map of Peary Channel

Robert Peary’s map. | Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

Robert Peary’s map. | Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainFew maps are flawless, but the errors on American explorer Robert Peary’s map of northern Greenland had fatal consequences [PDF]. Peary produced the map in the early 1890s, theorizing that northeast Greenland was an island separated by a waterway he named “Peary Channel.” If accurate, this would mean the land belonged to the United States, not Denmark.

In 1906, the Denmark Expedition embarked to verify Peary’s claims. Harsh conditions led to the deaths of three explorers. Hoping to retrieve maps and notes left in cairns, another team—Ejnar Mikkelsen and Iver Iversen—ventured out. Their findings confirmed that Peary Channel was nonexistent. Mikkelsen and Iversen faced extreme hardships and were rescued in 1912, the same year the first Thule expedition independently confirmed the area was a peninsula.

Halford Mackinder’s “The Natural Seats of Power”

While politics had influenced maps before, Halford Mackinder’s 1904 article “The Geographical Pivot of History” took geopolitical theory to new heights. His sketched map, “The Natural Seats of Power,” created by Bernard Vernon Darbishire, illustrated the idea that control over central Asia and Russia equated to global dominance. Mackinder’s map sparked discussions on geography’s role in politics and was later adapted by Nazi Karl Haushofer in 1935 to support theories of German expansion.

The Gall-Peters Projection

A map created using the Gall-Peters Projection. | Strebe, Wikimedia Commons // CC BY-SA 3.0

A map created using the Gall-Peters Projection. | Strebe, Wikimedia Commons // CC BY-SA 3.0Many attempts have been made to address the distortions of the Mercator map, with the Gall-Peters Projection being the most notable alternative. This projection uses a cylindrical format with latitude parallels at a 45-degree angle, ensuring countries are proportionally accurate in size. However, this comes at the cost of distorting landmass shapes, which appear vertically stretched.

Scottish cartographer James Gall first introduced the projection in 1855, but it gained little traction [PDF]. In 1973, German historian Arno Peters independently developed the same mathematical formula, bringing it to broader attention. Although adopted by UNESCO, UNICEF, and some educational institutions, the map faced criticism for merely replacing one type of distortion with another.

Google Maps

Since its launch in 2005, Google Maps has revolutionized navigation, now serving approximately 1 billion users monthly. Its widespread adoption highlights its integral role in contemporary life.

In 2012, Brian McClendon, Google Maps’ VP of Engineering, referred to the platform as “the endless pursuit of the perfect map.” The map is continuously updated to reflect new roads, structures, and evolving natural landscapes. Utilizing satellite imagery, aerial photos, and cameras mounted on vehicles—and occasionally sheep—Google Maps captures the dynamic world. Users can explore multiple views, including satellite imagery and immersive 360° Street View.