The way schools operated has drastically changed since the 19th and 20th centuries. From corporal punishment to lunch breaks to walking miles through snowstorms just to attend class, here are a few key differences in schooling a century ago, inspired by an episode of The List Show on YouTube.

1. Schools were set up within mills and factories across the U.S.

A century ago, many children worked, whether on family farms or in factories and mills, making the traditional 8 a.m. to 3 p.m. school schedule impractical. As a result, some kids attended school during nighttime hours [PDF], and in certain cities, providing evening classes for children was mandatory.

2. Attending school was less common in the past compared to today.

In 1900, only 51 percent of children between the ages of 5 and 19 were enrolled in school. This figure grew significantly over time, reaching 75 percent by 1940 [PDF], likely driven by education reforms and child labor laws.

3. High school enrollment was exceptionally low a century ago.

While high schools in the U.S. date back to the founding of Boston Latin School in 1635, high school attendance was particularly scarce 100 years ago. In 1900, just 11 percent of 14-to-17-year-olds attended high school; by 1920, the situation had scarcely improved: According to data from the National Center for Education Statistics, the “median years of school completed by persons age 25 and over” was only 8.2 years.

4. One-room schoolhouses were typical in rural areas.

In rural U.S. areas, there was typically a single schoolhouse with a single room, where one teacher taught all the students from grades one to eight. The students were arranged by age, with the youngest seated at the front and the oldest at the back. In contrast, cities had larger schools with several classrooms [PDF].

5. Work influenced the duration of the school year.

Today, most states mandate at least 180 days of instruction annually in public schools, but in 1905, the average school year consisted of only 151 days. Back then, children often missed more school days: the average student attended just 106 days per year. Kids working on farms, in particular, frequently missed school, typically taking the spring and autumn off to help with work.

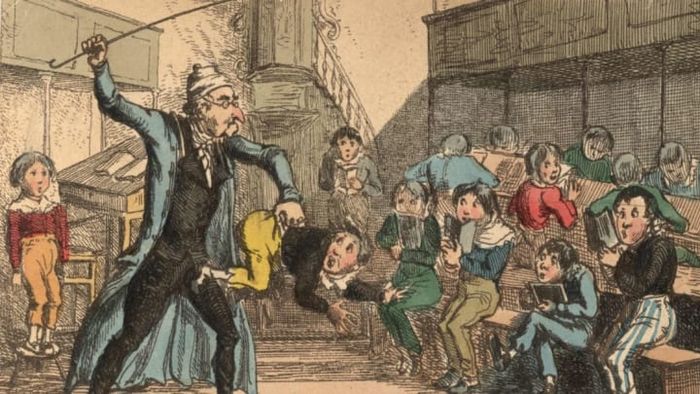

6. Corporal punishment was widely practiced.

In the early 1900s, corporal punishment was a common disciplinary measure. In 1883, the Board of Education in Franklin, Ohio, set out guidelines [PDF], which included this: “Pupils may be detained at any recess or no longer than fifteen minutes after the afternoon session ends, when the teacher deems it necessary for lesson review or discipline enforcement … Whenever corporal punishment is deemed necessary, it should not be administered to the head or hands of the student.”

Some school systems granted teachers more autonomy [PDF], allowing them to strike students’ knuckles with a ruler and use other forms of punishment, such as having a student repeatedly write the same phrase.

7. Some students were required to wear a Dunce cap.

When a child misbehaved, a teacher might place a pointed hat, called a Dunce cap, on their head and make them sit in a corner. (According to 19th-century accounts, some versions of the caps included bells to intensify the embarrassment.) Some recall this practice continuing into the 1950s as a form of punishment.

It’s

8. A century ago, the majority of teachers were women.

By 1919, roughly 84 percent of teachers were women, compared to 1800 when 90 percent of teachers were men. The profession became predominantly female as public education expanded in the mid-1800s. Education reformers, aiming to demonstrate that the system could be cost-effective, hired women for the new teaching roles, as they were paid much less than men.

9. In the past, boys and girls received different educational experiences.

Girls were often steered towards home economics and domestic skill-focused courses. In some areas, girls weren't even allowed to enter the school through the same door as boys.

10. Schools were racially segregated.

The schools attended by white children were far better funded than those for Black children, which frequently used outdated books and supplies passed down from white schools. Teachers in these two systems also faced significant pay disparities. Although school segregation was declared unconstitutional in 1954, achieving real equality remains a challenge for education reformers today.

11. The Pledge of Allegiance used to have different words.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, children began learning and reciting the Pledge of Allegiance, written by Francis Bellamy while working in a magazine marketing department in 1892. The original version was simply: “I pledge allegiance to my flag and the republic for which it stands; one nation indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.”

12. Memorization played a big role in school.

In subjects ranging from writing to math, the expectation was that students would memorize and recite key parts of their lessons. Homework mainly involved practicing that memorization. For example, here’s a passage from McGuffey’s Eclectic Readers, a textbook often memorized in those times: “This is a fat hen. The hen has a nest in the box. She has eggs in the nest. A cat sees the nest, and can get the eggs.”

13. Progressive education started gaining traction in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The movement was spearheaded by reformers such as John Dewey and Ella Flagg Young. Young, the first female superintendent of a major American city school system (Chicago), focused on teacher training and empowerment, along with her educational writings. These educators and philosophers advocated for a shift away from rote memorization and towards offering children more choices. They envisioned a classroom that was communal and democratic, with students participating actively rather than passively receiving instructions from a teacher at the front.

14. Some schools became small-scale versions of communities, with students taking charge.

While the full vision of progressivism was never realized, many schools adopted parts of it. In Gary, Indiana, for instance, schools were transformed into small communities. Students applied their practical skills to help run the school, which could involve cooking and serving lunch, building their own desks, or even tackling plumbing and electrical tasks in the school buildings (under supervision, of course).

15. Music classes were different—no recorders or “50 Nifty United States.”

A century ago, music classes in public schools generally focused on music theory, singing, or learning instruments. (This also meant that “normal schools” for teacher training included mandatory music courses.) Thankfully, for the ears of parents in the early 1900s, the recorder didn't become the typical beginner instrument until the mid-1900s. Kids in 1919 weren’t singing “50 Nifty United States,” either, since it wasn’t written until the 1960s. Instead, they sang songs like "A Cat-Land Law," "Looby Looby," "Song of the Noisy Children," and "Dollies’ Washing Day."

16. Gym class was sometimes referred to as 'physical culture.'

At the time, two of the most popular styles of physical education (or PC) were German and Swedish gymnastics. German gymnastics included activities like weightlifting, using balance beams, climbing ladders and ropes, and engaging in some cardio exercises like running. The Swedish method, on the other hand, utilized similar equipment but was more focused on whole-body exercises. It followed a more structured approach, with an instructor guiding the class through movements of increasing difficulty. As the 20th century approached, gym classes also started including lessons on hygiene and health.

While little research has been done on the history of recess, we do know that by 1919, many popular playground games had already been created, including jacks, red rover, hopscotch, and kickball. In fact, kickball was just starting to gain popularity in the U.S., having originated in Cincinnati in 1917.

17. By the end of the 19th century, some school lunch programs were taking shape.

School lunch programs began to emerge in cities like Philadelphia and Boston in the early 1900s. By the early 1920s, many schools across the country had adopted similar programs, offering hot meals like soups to their students.

18. Back-to-school shopping was still a tradition in the early 20th century ...

However, it wasn't quite like the shopping experiences we know today: No trips to Target, no Minions backpacks, or Trapper Keepers. A 1924 advertisement from a Montana store encouraged parents to let their kids shop for themselves, stating, 'Teach the children to make their own purchases economically and with taste. They're safe to shop here, as we'll gladly exchange or refund their money if their selections aren’t approved at home.'

19. ... But the school supplies were much different back then.

In classrooms, students primarily used a slate and chalk to complete their work since paper and ink were costly. A blackboard, usually located at the front of the room, was a common feature. Blackboards began to be manufactured around the 1840s. The Scottish educator James Pillans is often credited with inventing the blackboard. In the early 1800s, he supposedly combined several individual slates to create a large board, perfect for displaying maps during geography lessons.

20. Transportation to school wasn’t standardized in those days.

Students were expected to find their own way to school, which often meant hitching a ride on a wagon, carriage, or cart. The concept of school buses began to take shape in the early 20th century. By the early 1930s, there were around 63,000 school buses across the United States.

21. A century ago, it was sometimes illegal to teach a foreign language in schools.

For instance, Nebraska enacted a law in 1919 that prohibited teaching a foreign language until students had “successfully completed the eighth grade.” Iowa passed a similar law. And in the aftermath of World War I, even states without English-only laws on the books began removing German classes from their schools. In 1923, the Supreme Court ruled these laws unconstitutional.

Additional Sources: The World of Child Labor: An Historical and Regional Survey, Hugh D. Hindman; “The History of the Future of High School,” Vice; “A Brief History of Teacher Professionalism,” by Diane Ravitch, Ph.D.; “Education in the 20th Century,” Britannica.com; Sports Science Handbook: I-Z, Simon P.R. Jenkins; Introduction to Teaching Physical Education: Principles and Strategies, Jane M. Shimon.