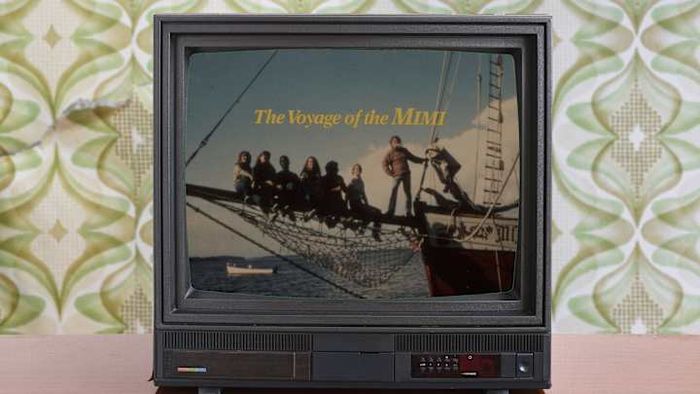

Premiering on PBS in 1984, The Voyage of the Mimi became a revolutionary educational science series. It was widely integrated into elementary and high school curriculums (including mine!) and enthralled children during the ‘80s and ‘90s. The show not only inspired a sequel but also launched Ben Affleck’s acting journey. Discover 30 lesser-known details about this iconic series.

1. The inspiration behind The Voyage of the Mimi came from a proposal by the U.S. Department of Education.

Courtesy Bank Street College of Education

Courtesy Bank Street College of EducationDuring the early 1980s, the U.S. Department of Education issued a call for proposals aimed at developing a middle school science curriculum utilizing multimedia tools such as TV, computer software, video disks, and teacher guides. “This was a pivotal moment when two significant trends intersected: the U.S. was declining as a global leader in science and math, and computer technology was emerging as a potential educational tool,” explained Lorin Driggs, who worked in the Publications Department of New York City’s Bank Street College of Education—the institution behind Voyage of the Mimi—in a 2014 interview with Mytour. “The Department of Education’s RFP aimed to inspire elementary students, including minorities and girls, to pursue science and math careers while showcasing the potential of microcomputing as a supplement to traditional teaching methods.”

2. The concept of The Voyage of the Mimi originated from pioneers in educational entertainment.

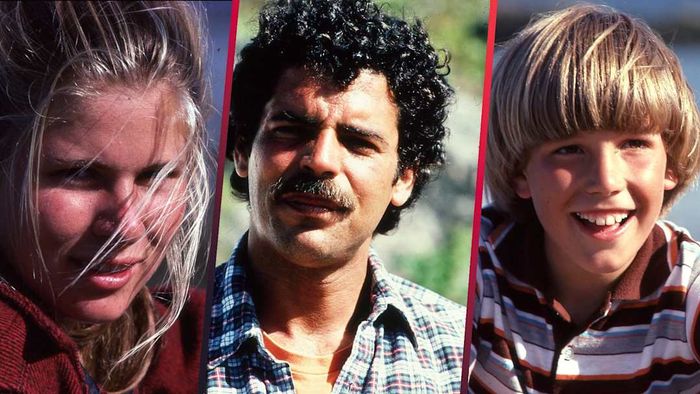

D’Arcy Marsh (center), the director and cameraman, and Peter Marston, the real-life owner and captain of the 'Mimi' who also played Captain Granville, pausing between takes. | Courtesy Bank Street College of Education

D’Arcy Marsh (center), the director and cameraman, and Peter Marston, the real-life owner and captain of the 'Mimi' who also played Captain Granville, pausing between takes. | Courtesy Bank Street College of EducationRichard Ruopp, the late president of Bank Street, assembled a dedicated team to craft the proposal and enlisted Samuel Y. Gibbon, Jr., a veteran producer from Children’s Television Workshop known for his work on Sesame Street and The Electric Company. At the time, Gibbon was developing what would become 3-2-1 Contact (initially titled "The Science Show") and expressed frustration, stating, “I couldn’t seem to find an engaging way to structure the show,” as he shared with Mytour in 2014. “The comedy variety format, which worked well for Sesame Street and The Electric Company, didn’t feel suitable for science. I believed we needed to inspire kids to immerse themselves in science, not just observe it passively.” Eager to contribute, Gibbon joined the proposal team and remained as executive producer after its selection. Lorin Driggs from Bank Street also played a key role, initially as Gibbon’s special assistant and later as managing editor for the program’s educational resources.

Once the Department of Education approved the series, Gibbon brought on Jeffrey Nelson—a producer for John Sayles’s films Return of the Secaucus Seven and Lianna—as the on-location producer. He also recruited filmmaker D’Arcy Marsh to direct and film the episodes. Dick Hendrick, a former student of Gibbon’s from Harvard during his hiatus from Children’s Television Workshop, was hired to write the scripts.

3. Insights from the research conducted for 3-2-1 Contact shaped the thematic focus of Voyage of the Mimi.

Courtesy Bank Street College of Education

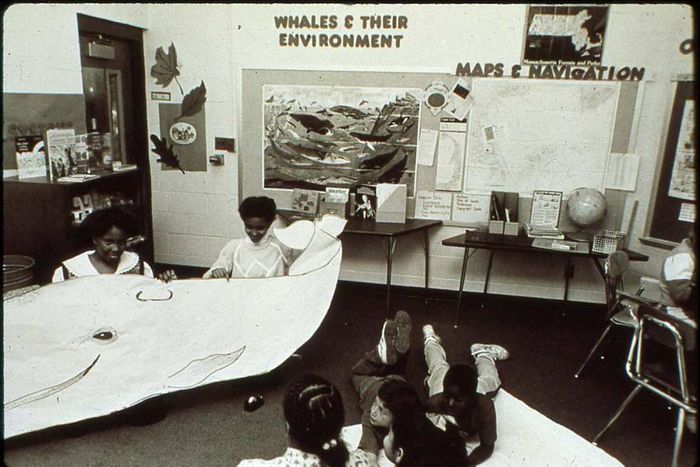

Courtesy Bank Street College of EducationGibbon’s formative research at the Children’s Television Workshop revealed that children found plot-driven shows more engaging than those without a storyline. “Even a comedic sketch with a narrative arc was favored over random jokes—and semi-serious or dramatic stories were the most captivating,” he explained. “This observation reinforced my belief that science could be effectively taught through storytelling.” The team proposed a 13-episode series, with each episode divided into a 15-minute dramatic segment and a 15-minute documentary-style “expedition,” hosted by one of the young actors, showcasing real-world scientists in action.

The show’s concept was inspired by Gibbon’s experience with 3-2-1 Contact, particularly an idea for a magazine article about a sick whale. Testing revealed that this topic was “by far the most captivating to kids,” he noted. Additionally, at the time, “whales were still largely mysterious, with limited research available. I found the subject fascinating and shared it with my colleagues.” The dramatic segments would feature a diverse cast aboard a sailboat chartered by two marine biologists—one male and one female—studying humpback whales. They would be accompanied by two high school students, the captain’s grandson, and a Deaf graduate assistant. “Frank Withrow, who led technology and education projects at the Department of Education, began his career as a teacher for the Deaf,” Gibbon said, emphasizing the importance of including a Deaf character.

4. The Voyage of the Mimi was guided by a board of science advisors.

Courtesy Bank Street College of Education

Courtesy Bank Street College of Education“We worked closely with consultants and an advisory board that convened regularly throughout the project,” Driggs explained. The board included 18 members, such as math expert Magdalene Lampert, author of Building a Better Teacher; Ted Ducas, a Wellesley College professor specializing in whale-related physics; Kristina Hooper, a cognitive scientist who later established Apple’s Multimedia Lab; Bob Tinker, a pioneer in science probeware design; and various educators and faculty from Bank Street.

5. The Voyage of the Mimi faced several unique challenges as a children’s show.

A youthful Ben Affleck steering the 'Mimi.' | Courtesy Bank Street College of Education

A youthful Ben Affleck steering the 'Mimi.' | Courtesy Bank Street College of EducationNelson was thrilled yet anxious about the Mimi project. Unlike most children’s shows filmed in studios, Mimi required shooting at sea and on a secluded island off Maine’s coast. The cast was primarily children, and the production relied heavily on unpredictable factors like whale appearances and weather conditions. “We needed whales for key scenes, ideal weather, and even a dramatic storm,” Nelson shared with Mytour in 2014. “What if the actors got seasick? What if the whales didn’t show up? What if the storm was too mild—or worse, too dangerous? These uncontrollable elements made the production far more complex than a typical children’s TV show.”

6. Marsh nearly turned down the opportunity to work on The Voyage of the Mimi.

Affleck and Marsh. | Courtesy Bank Street College of Education

Affleck and Marsh. | Courtesy Bank Street College of EducationMarsh faced a tough decision: join the second unit filming for Gorillas in the Mist—featuring gorillas he had filmed years earlier with Dian Fossey—or direct Mimi. After meeting Gibbon, he was convinced that Mimi was the more meaningful project. “Mimi ultimately felt far more significant,” he remarked. (Marsh later contributed to The Making of Gorillas in the Mist.) His choice proved wise, especially for a major reason we’ll explore shortly.

7. Captain Granville was the first role cast for The Voyage of the Mimi.

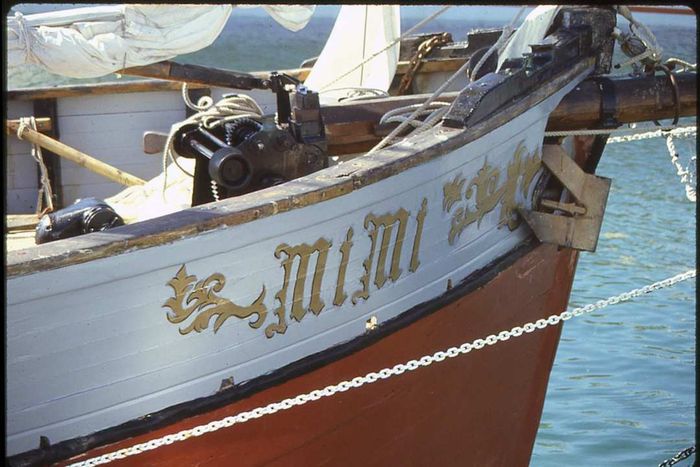

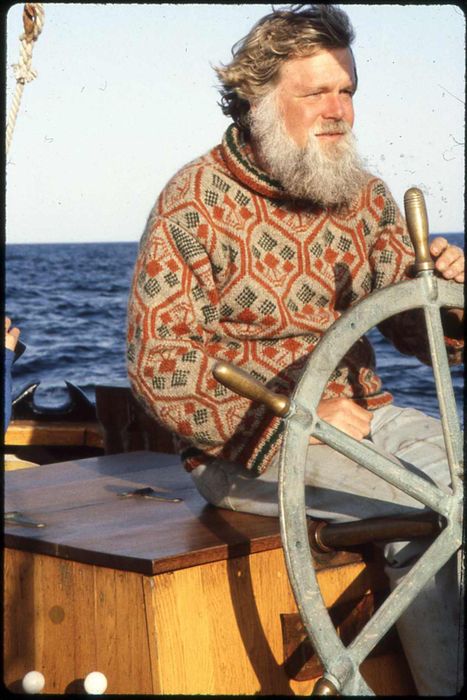

Peter Marston, the owner of the 'Mimi.' | Courtesy Bank Street College of Education

Peter Marston, the owner of the 'Mimi.' | Courtesy Bank Street College of EducationWhile searching for a boat for the series, Gibbon consulted friends he had met during his teaching stint at Harvard between producing The Electric Company and 3-2-1 Contact. They suggested MIT professor Peter Marston’s boat, a converted tuna trawler turned sailboat. “I visited Peter, and he was fascinating—with his beard, he looked the part of an experienced skipper and had strong ties to the scientific community,” Gibbon recalled. Marston, a plasma scientist, was easily persuaded to join the cast. “Peter had to be part of the project because he was the only one who understood the boat’s quirks,” Gibbon explained. “Plus, he was a natural performer—he sang sea shanties and participated in local theater. Transitioning to the role of Captain Granville was seamless for him.”

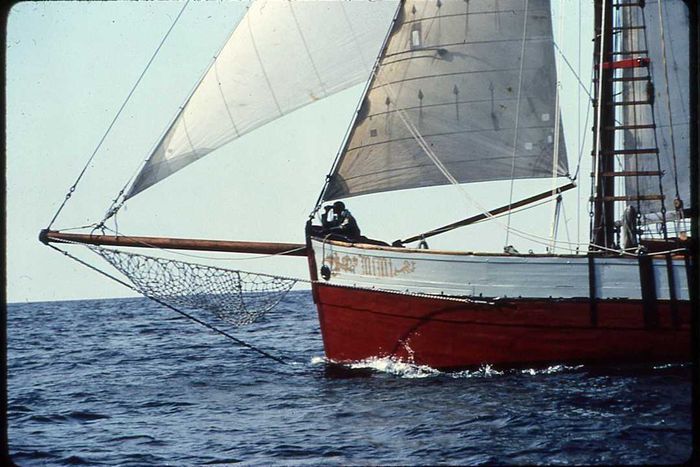

8. The Mimi featured in The Voyage of the Mimi has an intriguing backstory.

The 'Mimi.' | Courtesy Bank Street College of Education

The 'Mimi.' | Courtesy Bank Street College of EducationConstructed in 1931 in Camaret, France, the 72-foot vessel initially served as a cargo barge. During World War II, German troops repurposed it to transport munitions. At some point, it sank in France and was left in ruins until the 1960s, when a Frenchman purchased it. Along with his family and two others, he restored the Mimi with plans to sail it globally. However, during the conversion from trawler to sailboat, “they overlooked acquiring masts and lacked funds,” Marsh recounted. “They resorted to cutting masts from a decaying national monument shipwreck, loading them onto a truck at night, and evading police in a car chase. Despite their impractical idealism, they did an excellent job refurbishing the boat.” However, conflicts arose early in their journey, leading the owner to sell the Mimi to Marston, who retained ownership until 1999.

9. Real children provided feedback on parts of The Voyage of the Mimi.

Gibbon emphasized testing nearly every aspect, from audition tapes of potential cast members to educational materials and rough documentary cuts. This task fell to individuals like Bill Tally, who joined Bank Street’s Center for Children and Technology (now independent) after graduating in 1983. (In 2014, Tally was still a research scientist there.) “As formative researchers, our job was to provide producers with timely feedback on what resonated—or didn’t—with kids in rough cuts, storyboards, scripts, or software prototypes,” Tally explained. “We gathered small groups of 4 to 10 children from Bank Street School for Children and nearby NYC public schools, observing as they watched, interacted with, and discussed the materials.”

Nearly all rough cuts of the expeditions were reviewed by children. “We made adjustments to every one based on their feedback,” Tally noted. “Changes often involved editing and reordering segments to clarify concepts, enhance the scientists’ appeal, and spark kids’ curiosity.”

For instance, in the rough cut of the “Boatshop” expedition, archived documents at Bank Street reveal that children found the scenes of boat makers bending wood uninteresting. One child remarked, “everybody talked too much,” while another echoed, “It gets boring because they just talk, talk, talk, talk. Not enough action.” Based on this feedback, researchers suggested trimming lengthy, non-essential segments and incorporating “more humorous moments to lighten the documentary,” as noted in the records.

“The producers didn’t always welcome our suggestions,” Tally admitted. “There’s an inherent conflict between crafting engaging narratives and ensuring scientific concepts are accessible to kids. This created a dynamic, productive tension between the production team in the basement and the research team on the 6th floor at BSC. Debating and refining each piece was both challenging and enjoyable.”

10. Following the filming of the The Voyage of the Mimi pilot, two roles were recast.

Judy Pratt, Edwin De Asis, and Ben Affleck. | Courtesy Bank Street College of Education

Judy Pratt, Edwin De Asis, and Ben Affleck. | Courtesy Bank Street College of EducationIn July 1982, the team filmed a pilot episode featuring Marston as Captain Clement Tyler Granville, a young Ben Affleck—later known for Batman—as his grandson C.T., Edwin De Asis as scientist Ramon Rojas, Judy Pratt as graduate research assistant Sally Ruth Cochran, Mark Graham as Arthur Spencer, and MaryAnn Plunket as scientist Ann Abrams.

Affleck had previously appeared in a low-budget film directed by Marsh; Mimi marked only his second acting role. “During auditions for C.T., D’Arcy recommended Ben,” Gibbon recalled. “Ben was incredibly charming. Coming from a film-savvy family, he had some on-camera experience and was a natural performer. No other candidate came close.” Pratt was discovered at Gallaudet University, a renowned institution for the Deaf and hard of hearing.

The pilot was filmed over a month. Following its completion, the National Science Foundation partnered with the Department of Education to fund the full series, with production scheduled for the following summer to align with the children’s school schedules. However, two roles required recasting: one actress, initially cast as high school student Rachel, struggled with self-consciousness and emotional expression, leading to her replacement by Mary Tanner. Meanwhile, Plunket exited the project to take over Amanda Plummer’s role in Broadway’s Agnes of God, prompting the hiring of Victoria Gadsden as Ann Abrams. After two weeks of rehearsals in Gloucester, filming for The Voyage of the Mimi officially commenced in summer 1983 and lasted two months.

11. Gadsden immersed herself in research to authentically portray a scientist in The Voyage of the Mimi.

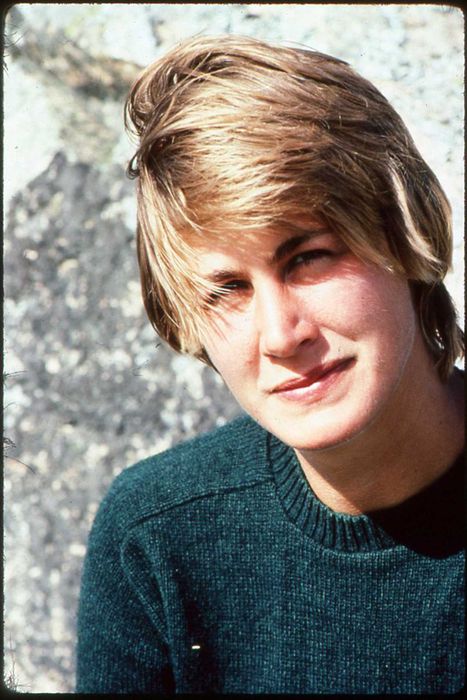

Victoria Gadsden. | Courtesy Bank Street College of Education

Victoria Gadsden. | Courtesy Bank Street College of EducationGadsden’s role required her to be proficient in sign language to interact with her Deaf research assistant. “My top priority before heading to New York was mastering sign language,” she explained. “I did my best to learn, and during filming, Judy Pratt had an interpreter named Jo by her side at all times—ensuring Judy was fully included in every conversation. Judy and Jo helped me improve my signing. While I didn’t achieve fluency, I could communicate effectively with Judy and learned to deliver my lines in sign language.” Gadsden also spent time with a scientist from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution on a whale-watching trip, gaining valuable insights for her role.

12. The Voyage of the Mimi was filmed with a minimal crew.

The cast and crew filming a scene on Dyer Island, Maine. | Courtesy Bank Street College of Education

The cast and crew filming a scene on Dyer Island, Maine. | Courtesy Bank Street College of EducationMarsh directed and filmed the series on 16mm with a small team: Alongside a chase boat operated by producer John Borden and its camera crew, the Mimi had an assistant cameraman, a sound technician, a lighting specialist, a continuity person, and a producer. The cast occasionally pitched in as well. “The Mimi couldn’t accommodate many more people,” Marsh noted. “I mostly shot handheld, only using a tripod for long-distance shots of the boat at sea. I used a Bosun’s chair to move up and down while the crew climbed the rigging.”

13. The scene expected to be the most challenging in The Voyage of the Mimi turned out to be surprisingly easy to film.

Tagging a whale. | Courtesy Bank Street College of Education

Tagging a whale. | Courtesy Bank Street College of EducationNelson anticipated difficulties with the scene where fictional scientist Ramon tags a whale using a crossbow. Since De Asis couldn’t perform the task, the team flew in the only scientist authorized to tag whales from California. Dressed as Ramon, he approached a whale in a Zodiac and used a crossbow with a suction-tipped arrow to attach the transmitter. “We needed calm waters, a stationary whale, and a clear shot of the scientist firing the arrow, with the Mimi crew watching in the background,” Nelson explained. “I thought the odds of everything aligning perfectly were slim.” He humorously requested calm weather and for the whales to arrive on set by 8 a.m.

His concerns were unnecessary: The weather was perfect, the whales arrived precisely on schedule, and the scientist nailed the shot. The entire sequence wrapped by 9:30 a.m., following the script perfectly. “We were amazed, thrilled, and immensely relieved,” he recalled. “I expected it to be the toughest scene, but it ended up being one of the simplest. It was one of the most memorable days I’ve ever had on set.”

For Gadsden, it was an unforgettable experience. “I joined the scientist in the Zodiac, took the wheel, and got within arm’s reach of a whale as he tagged it,” she shared. “It was an extraordinary day—absolutely incredible.”

14. Ben Affleck proved to be a consummate professional.

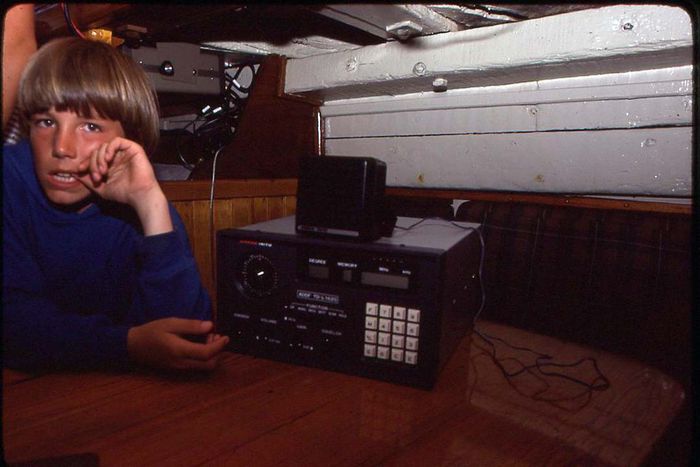

Affleck aboard the Mimi, tuning in to signals from the whale’s radio transmitter. | Courtesy Bank Street College of Education

Affleck aboard the Mimi, tuning in to signals from the whale’s radio transmitter. | Courtesy Bank Street College of Education“I’ve worked with many who later became celebrities, and they share a common trait—intense focus,” Gadsden remarked. “It’s no surprise Ben achieved such success. He was charming, for starters, and incredibly driven—mature, focused, and career-oriented even back then.” Affleck, who had starred in the pilot, even briefed Gadsden on the project’s background and offered advice. “He was a delightful, fun kid who loved bringing everyone together,” she recalled. “I’ll never forget running into him on a day off; he had bought us all cheesy name tags like waitresses wear, thinking it’d be fun. That was just Ben.” The 11-year-old actor also wrote to his classmates and his brother Casey, “who was disappointed to miss out.”

15. Seasickness occasionally disrupted filming on The Voyage of the Mimi.

The Mimi sailing at sea. | Courtesy Bank Street College of Education

The Mimi sailing at sea. | Courtesy Bank Street College of EducationMarsh, a former camp counselor, understood that “kids, like soldiers, rely on their stomachs.” On the cast’s first voyage aboard the Mimi, he brought a box of Dunkin’ Donuts Munchkins. “Everyone happily ate them in the car,” Marsh said. “We reached the dock, boarded the boat, and the harbor was calm. But as soon as we passed the breakwater into open ocean, we hit massive waves from a distant hurricane. The boat rocked violently, and everyone got seasick,” he laughed. “So much for the Munchkins.”

Gadsden was one of the few who never experienced seasickness. “Some people really struggled,” she said. “But I was fine. During the storm scene, everyone except me, Peter, Judy, and D’Arcy got sick. At one point, while others were vomiting, we stayed on deck, doing whatever was needed.”

16. The Mimi’s previous owner came back to assist with filming a pivotal scene.

While Marston acted, Kate Cronin took over as skipper. “He kept a close eye on her, and she was understandably nervous,” Marsh recalled. “Once, she accidentally scraped the boat against the dock!” For a scene requiring the Mimi to be beached on a remote Maine island, Marston enlisted the help of the boat’s former French owner. “He was incredible—‘ah, no problem, no problem!’” Marsh said. “He brought the Mimi in during high tide, let the tide recede, and we filmed the entire sequence between tides. We had about six hours to shoot with the boat tilted, but it never felt rushed.”

17. The whales were remarkably cooperative—and awe-inspiring.

“Early on, we warned Sam, ‘There’s a good chance we might not see any whales,’” Marsh remembered. “But that summer, humpback whales were everywhere.” A second boat captured stunning close-ups of the whales, while Marsh, shooting handheld, climbed the rigging to film the cast interacting with them. “We sailed to their location, and the whales approached the boat—visible in the footage. It was incredible. People spend years trying to get shots like that.” Nelson added, “There were moments when we’d be at sea on a perfect day, watching humpbacks breach or swim alongside the boat, and I’d think how lucky I was to call this a job. Seeing these majestic creatures up close was unforgettable—as was the unforgettable stench of their breath when they exhaled nearby.”

Even Edwin De Asis, a New York City native and science teacher-turned-actor who portrayed Ramon, was awestruck by the experience. “New Yorkers aren’t easily impressed,” he wrote in promotional materials. “But trust me, anyone—even New Yorkers—would be amazed watching a humpback whale breach. Even the most jaded observers would take a second look, and that’s saying something.”

18. A romance blossomed on the set of The Voyage of the Mimi.

Marsh and Gadsden met during filming in the Gulf of Maine, and their relationship quickly developed. “D’Arcy began his romance with her during production, much to the envy of others in the group,” Gibbon recalled with a laugh. The couple eventually married.

19. The Voyage of the Mimi nearly featured a rock ’n roll soundtrack.

Gibbon envisioned rock ’n roll music for the series, but Marsh advocated for a more traditional score. To settle the debate, they tested both styles over the shipwreck scene where the Mimi runs aground and Captain Granville suffers hypothermia. “One version had flute and guitar, while the other used music from [the movie] Day of the Dolphin,” Marsh explained. The episode remained identical except for the music. Gibbon and researchers screened both versions in classrooms and gathered feedback.

“The kids who watched the version with the rock soundtrack described it as, ‘They land, Captain Granville collapses from hypothermia, and then they explore the island,’” Marsh explained. “The group that saw the version with the movie score said, ‘They land on an island, Captain Granville collapses and nearly dies, they realize they’re stranded, and then they save him by keeping him warm, and he survives.’” The movie score helped students better understand the narrative, so it was kept for the series.

20. The theme music for The Voyage of the Mimi was created by Jeff Lass, with input from Marsh.

Marsh had specific ideas for the theme: “I told Sam, ‘We need a theme that mirrors the journey—building excitement, reaching a peak, and then descending.’ That’s why the music feels like climbing and descending a hill.” Marsh shared this vision with composer Jeff Lass, whom he described as “brilliant. He took my concept and brought it to life musically.” The catchy theme remains one of the most memorable aspects of Mimi.

21. The “expeditions” in The Voyage of the Mimi were filmed after completing the dramatic episodes.

Each mini-documentary featured one of the young actors, out of character, hosting and visiting real scientists whose work tied into the episode’s storyline. “We wanted to show real science, not just the glamorous, fictional version,” Gibbon said. “It was important to ground the story in reality and highlight actual scientists at work.” Affleck, Graham, Tanner, and Pratt visited locations like the New England Aquarium, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, the New Alchemy Institute, and the Mt. Washington Weather Observatory. (Bank Street’s archives include a permission slip signed by Affleck’s mother, allowing Nelson and Hendrick to take him on these trips and assume full responsibility for him.)

22. Researchers used analog methods to test The Voyage of the Mimi’s computer-based materials.

Courtesy Bank Street College of Education

Courtesy Bank Street College of EducationDuring the development of Mimi, computers were not yet common in classrooms. To evaluate the software concepts, Tally and his team tested paper prototypes before coding began. “We used rough screen mock-ups created by the programmer and tested them with students at Bank Street School—before school, during lunch, and after school,” Tally explained. “Sam’s vision was to mirror how adults and scientists used real tools in the classroom: simulations, programming environments, modeling tools, and data recording and graphing tools.”

The research led to adjustments in the materials: “A key example was the 'Rescue Mission' game,” Tally noted. “Initially, the game involved navigating toward a Target Ship, which engaged boys but not girls. When we asked why, boys used video game terms like 'hitting the target,' while girls showed little interest. After consulting with producers, we reworked the story and visuals, turning the ship into a fishing trawler that accidentally caught a whale. The new goal was a 'Rescue Mission,' which equally captivated girls and boys. This change was crucial, given the project’s aim to address the decline in girls’ interest in science and math during middle school.”

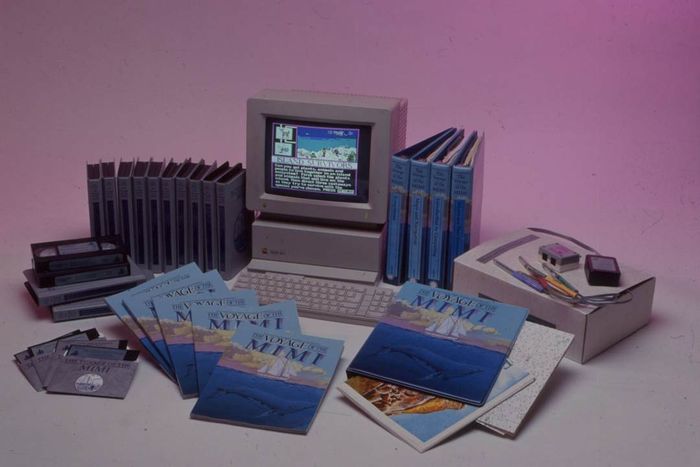

'The Voyage of the Mimi' educational package. | Courtesy Bank Street College of Education

'The Voyage of the Mimi' educational package. | Courtesy Bank Street College of EducationAlongside 'Rescue Mission,' which taught geo-spatial mapping and navigation, other software included 'Island Survivors,' a game similar to Sim City where kids modeled island ecosystems and aimed to survive multiple seasons, and 'Lab Tools,' which let students connect probes to Apple IIe computers to measure and graph heat, light, and sound data. “They conducted experiments comparing their environment to the whale’s,” Tally explained.

23. An episode of The Voyage of the Mimi faced bans in certain states.

In 'Tracking the Whales' and 'Shipwrecked,' the Mimi is damaged and starts flooding, leading to Captain Granville being swept overboard. After being rescued, he suffers hypothermia. To save him, Ramon and Arthur strip down and share a sleeping bag with Granville. “We knew it was provocative, but it was intentional,” Gibbon said. “It demonstrated how to treat hypothermia—heat transfer through direct contact, not just air. It was a deliberate choice.” However, the scene sparked controversy; Marsh noted it was banned in three states, including Texas, due to concerns about “near-naked adults sharing a sleeping bag with kids.”

The scene also caused issues with the educational materials. Gibbon recalled, “When the salesman responsible for selling the materials in Texas and other conservative southern states saw the illustration in the book, he said, ‘I can’t show this to teachers here—they’ll be outraged.’ We were crushed when they demanded we replace the illustration.” Ruopp convinced the distributors to keep the story intact but allowed the illustration to be changed. “The publisher had to commission a new painting,” Gibbon explained, “and they had to cut out the original page from all the bound books in the warehouse and replace it with a less controversial image.”

24. The Second Voyage of the Mimi was approved before the first series even aired.

The Second Voyage of the Mimi explored Maya archaeology, blending social studies, language arts, science, and math. “We decided to pursue funding for the sequel shortly after finishing production on the first series,” Gibbon said. “We had tested enough material to feel confident it would succeed.”

However, the sequel nearly didn’t happen. Gibbon noted, “The Reagan administration attempted to cut funding for the second Voyage of the Mimi. We were already filming in Mexico when they tried to cancel the project. Fortunately, Frank Withrow from the Department of Education convinced them otherwise.”

25. Affleck’s mother took on the role of teacher for the kids during filming of the sequel in Mexico.

“Chris is an amazing teacher,” Marsh said. “Her first lesson in Mexico was a math class where students converted U.S. dollars to Mexican pesos and back. The second lesson was Social Studies—students spent Mexican currency at local shops. She had a knack for turning any situation into a learning opportunity.”

26. Gibbon refused to compromise on scientific accuracy for a scene in The Second Voyage of the Mimi—and it paid off.

Margaret Honey, now president and CEO of the New York Hall of Science, joined after the first Mimi to conduct formative research for the sequel. She recalled the crew returning from filming a challenging scene, “looking exhausted. They complained about going three days over schedule and over budget. As a young observer, I listened intently, and someone mentioned, ‘Sam wouldn’t fake the science.’ I asked, ‘What does that mean?’”

In the second season, the Granvilles and archaeologists search for a Mayan stele linked to a smuggling plot and a lost city. They find the stele underwater and must devise a scientifically accurate way to raise it. The production team used a lightweight fiberglass replica instead of a 5000-pound stele. “Sam insisted on a realistic method,” Honey explained. “They tied ropes around the stele and inflated sturdy garbage bags with air from divers’ tanks. This approach extended filming by three days and blew the budget.”

Despite the delays and costs, the effort was worthwhile. When Honey showed the rough cut to students in Harlem, “they were captivated and asked countless questions,” she said. “The episode was a huge success.” A week later, she returned to the classroom, and the teacher pointed her to a student named Jose. “Jose excitedly told me he recreated the scene in his bathtub,” Honey recalled. “He used a brick for the stele and string for ropes. When I asked about the air, he said, ‘I tried bendy straws, but they didn’t work well.’ I was amazed. That’s the magic of Mimi.”

27. A third Mimi series was once considered.

It would have explored the Mississippi River from multiple perspectives—geological, historical, and engineering—including the Native American mound-builders along its banks. Gibbon drew inspiration from John McPhee’s book The Control of Nature, which detailed the Army Corps of Engineers’ efforts to control the river. “The idea of controlling the Mississippi is absurd,” Gibbon said. “But the ongoing struggle to prevent flooding and maintain navigation is fascinating and complex. We envisioned a curriculum covering the river’s biology, fluid mechanics, economy, and history. It’s still thrilling to think about.”

Unfortunately, funding fell through. “By then, the first Bush administration was in power, and they weren’t keen on funding educational TV,” Gibbon explained. “Republicans focused on cutting government spending. We were fortunate to have launched earlier. Shows like Sesame Street and The Electric Company succeeded thanks to the Johnson administration. The acclaim for those shows helped us complete the first two Mimi seasons, but afterward, conservative policies prevailed.”

28. The Voyage of the Mimi has some unexpected fans.

Years later, while filming the fishing series The Salt Water Fisherman, Marsh met a tough Portuguese captain from New Bedford. “He had saved lives during a hurricane and served time for drug smuggling,” Marsh recalled. “He claimed he was framed. When he asked about my work, I mentioned Spenser: For Hire and Mimi. He said, ‘Voyage of the Mimi? In prison, we watched two shows: NYPD Blue and The Voyage of the Mimi.’ He knew every character by heart.”

29. The Mimi embarked on a tour.

In the early 1990s, Marston spent several days each week sailing the Mimi to East Coast ports. Students who had watched the show could board the ship, explore its history, and join the Captain in singing sea shanties.

30. The Mimi met an unfortunate end.

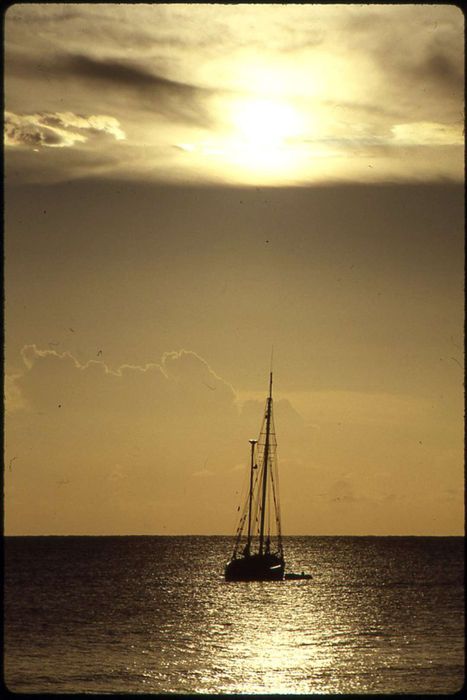

The 'Mimi' sailing at sunset. | Courtesy Bank Street College of Education

The 'Mimi' sailing at sunset. | Courtesy Bank Street College of EducationIn 2010, Joe Fraker and Dan Koopman, University of Vermont alumni and childhood fans of The Voyage of the Mimi, searched for the ship during a Boston visit. They discovered it deteriorating in East Boston bay, its hull rotting. Experts estimated a $1.2 million repair cost, but funds couldn’t be secured. By 2011, the Mimi was dismantled, with most of its wood repurposed as mulch.

A special thanks to Jeffrey Nelson for making this story possible, and to Lindsey Wyckoff at Bank Street for granting us access to the Mimi archives!