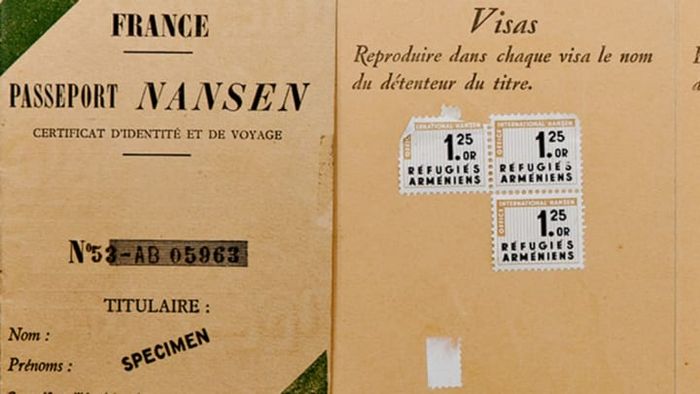

Conceived by a former polar explorer, the Nansen passport emerged as the inaugural legal travel document for refugees. Fridtjof Nansen, an adventurer who later became a Norwegian diplomat, devised this document after being appointed the League of Nations' first High Commissioner for Refugees. In 1922, addressing the refugee crisis in Europe, he introduced the identity document named after him. (That same year, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.)

The Nansen passport enabled over half a million stateless individuals—displaced by World War I, the Armenian genocide, and the Russian Revolution—to regain their ability to travel internationally and verify their identities. Issued annually, Nansen passports were distributed until the 1940s, when they were replaced by the London Travel Document following World War II. While most users were ordinary people, the passport also became a crucial tool for several notable figures. Today, as Google honors Nansen's 156th birthday with a Google Doodle, we reflect on the impactful document created in his honor.

1. VLADIMIR NABOKOV

Giuseppe Pinovia Wikimedia // Public Domain

On December 15, 1921, the Soviet government issued a decree stripping citizenship from a significant portion of its expatriate population. Vladimir Nabokov was among the nearly one million Russians who fled the country post-revolution. For years, Nabokov relied on Nansen passports for travel. Like many Russian intellectuals, he settled in Berlin, where he met and married his Russian-born wife. However, as she was Jewish, the couple escaped Nazi Germany in 1937, moving to Paris. France had become a haven for many Russians after the revolution, and Nabokov’s character Colonel Taxovich in Lolita (1955) is often seen as a symbol of the exiled Russian in Paris, grappling with diminished status and opportunities.

Nabokov’s temporary documents frequently caused difficulties. In his memoir, Speak, Memory, he describes the Nansen passport as “a feeble green document that marked its holder as little more than a parolee, subjected to grueling ordeals whenever crossing borders, with smaller countries often causing the most hassle.” In his short story, “Conversation Piece, 1945,” the narrator holds a “tattered sea-green” Nansen passport, missing a stamp “rudely denied” by a French consul. In 1940, Nabokov and his wife Vera left France for the United States, where he gained citizenship in 1945. Following the success of Lolita, which secured his financial future, he spent his final years near Lake Geneva at the foot of the Swiss Alps.

2. MARC CHAGALL

Pierre Choumoff via Wikimedia // Public Domain

Marc, originally named Moïse Shagal (sometimes referred to as Moyshe Segal), was born to a Hasidic Jewish family in what is now Belarus. Initially, the young artist supported the Bolshevik Revolution and even worked for the government. However, after facing ideological conflicts with fellow artists and financial struggles, he relocated to France in the early 1920s. The exact timing of his statelessness is unclear, but he likely used Nansen passports after moving to France in 1923, before gaining French citizenship in 1937.

Although Chagall eventually obtained French citizenship, he lost it again in 1941. When the Nazis rose to power, Chagall, along with thousands of other Jews in occupied France, was stripped of his nationality.

Fortunately, Chagall was secretly transported out of France by supportive Americans and spent the remainder of the war in New York. His French citizenship was reinstated after WWII, and he returned to France, where he lived until his passing in 1985.

3. ROBERT CAPA

Getty Images

Robert Capa, originally named Endre Friedmann and born in 1913, led a tumultuous life. As a young Hungarian, he faced trouble for opposing his country’s fascist regime and relocated to Berlin in his late teens. He stayed in Germany until Hitler’s ascent forced him to flee to France in 1933.

In Paris, he encountered Gerda Taro, a fellow Jewish refugee. She inspired his reinvention as Robert Capa, a fictional “American” photographer who found it easier to sell his work to French publications. The duo, both professionally and romantically linked, documented the Spanish Civil War together. Taro died during a solo assignment in Spain in 1937, but Capa continued his work, covering World War II. He followed the Allies through North Africa and Europe, famously capturing the D-Day landings for LIFE magazine.

Post-war, Capa’s life shifted. He photographed celebrities, dated Ingrid Bergman, and traveled extensively. Though he technically moved to the U.S. in 1939, likely on a Nansen passport after losing his Hungarian citizenship due to legal changes, he became an American citizen in 1946. Despite this, he continued working in conflict zones. Tragically, he was killed by a landmine in Thai-Binh, modern-day Vietnam, while covering the French Indochina War in 1954. He was only 40 at the time of his death.

4. IGOR STRAVINSKY

Getty Images

Born in Russia in 1882, Stravinsky grew up in a musical household and had already gained international recognition as a ballet composer by the time World War I began. He composed for the Ballets Russes, a traveling dance company, many of whose members later relied on Nansen passports. His groundbreaking work, Rite of Spring, premiered in Paris in 1913. When the war broke out, Stravinsky relocated his family to Switzerland.

Politically, Stravinsky supported the monarchy in Russia and had no desire to return home. By accepting a Nansen passport in the early 1920s, he effectively “renounced his Russian nationality,” as noted by his biographer Richard Taruskin. He settled in France, becoming a French citizen in 1934, before moving to California in 1940 and obtaining U.S. citizenship in 1945. His first trip back to the U.S.S.R. occurred in 1962, when he was invited by Nikita Khrushchev, but he spent the remainder of his life as an American.