If you find it tricky to distinguish the Maya from the Aztecs, wonder about the fate of this once-great civilization, or are confused by that whole end-of-the-world-prediction thing, we're here to clear up some of the most popular misconceptions about the Maya, inspired by an episode of Misconceptions on YouTube.

1. Myth: The people should be called Mayans.

The term Mayan doesn’t actually exist in Spanish or in any of the Mayan languages. The confusion stems from mixing up the name of a people with the language they speak. The only place you’ll still find the term Mayan widely used is in the study of linguistics, where it refers to a family of about 30 languages spoken by the Maya.

Today, scholars generally agree that the term Maya is the preferred one, even when used adjectivally. So, we say the Maya civilization, Maya culture, and the group of people known as the Maya (or, in Spanish, Los Maya).

2. Myth: There was a centralized Maya Empire.

Mayan languages include Yucatec, Quiche, Kekchi, and Mopan [PDF], and at one time, people in the Yucatán Peninsula were primarily identified by these languages, not by the overarching label Maya. (Interestingly, there is also a specific Mayan language called Maya.) The Maya people we know today spanned vast regions and a history of thousands of years.

In the latter half of the 20th century, a movement began to recognize the shared identities of various Maya groups. This has been called the Maya Movement or the Pan-Maya Renaissance, among other names. So, in certain contexts, the Maya can be considered a unified group. However, the diversity within that group highlights an important point: By most definitions, the Maya were never truly an empire.

A key aspect of empire-dom is often a centralized ruling power, as seen in the Roman Empire, as well as the Aztec and Inca Empires (which, for the record, emerged more than a thousand years after the Maya first rose in Central America). Though the various Maya city-states shared religious beliefs and an understanding of the cosmos, they never united like empires do. Local rulers might gain prominence and dominate nearby factions, but there was never a single emperor overseeing the whole Maya civilization. Plus, these interconnected city-states didn’t always get along.

3. Myth: The Maya were either brutal killers or entirely peaceful.

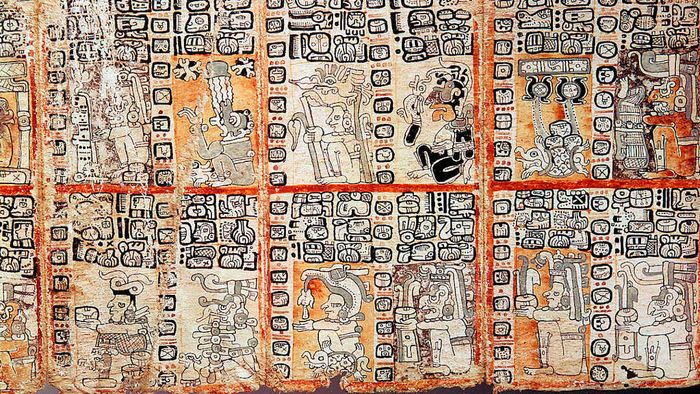

A section from the 15th-century Mayan Troano Codex. | Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty Images

A section from the 15th-century Mayan Troano Codex. | Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty ImagesIn the early 1900s, the Maya were often portrayed as a uniquely peaceful people, perhaps in contrast to the more violent Aztecs. While it's true the Maya practiced human sacrifice, their approach was less brutal than other cultures: By focusing on capturing and sacrificing specific elite enemies, the Maya avoided total warfare, leaving most of their society unaffected by conflicts between city-states.

The misconception may have lingered partly because ancient Mayan writing wasn’t fully deciphered until recent decades. However, there’s some truth to the idea: Maya rulers often boasted titles like “he of the twenty captives” or “he of the three captives,” which led some to believe the Maya were solely a peaceful civilization, centered on agriculture and astronomy.

A closer look at the historical evidence complicates the peaceful image often associated with the Maya. Some Maya rulers clearly engaged in warfare for traditional reasons like territory and resources. While scholars once thought that large-scale conflict between city-states only emerged in the later Maya period, more recent findings challenge that view. In 2019, a researcher from the University of California Berkeley, along with colleagues at the U.S. Geological Survey, dated a layer of thick charcoal at the bottom of a lake in Northern Guatemala to between 690 and 700 CE, during the Classic Maya period. This geological evidence, along with records of a “burning” campaign by a nearby rival city, suggests that total warfare had indeed taken place.

If the researchers' analysis holds up, the Maya weren’t simply fighting in ritualistic ways. Evidence points to efforts to ensure entire populations felt the impact of warfare—such as the destruction of a whole city by fire. While this is just one case, other evidence, like mass burial sites and fortified cities, paints a more warlike picture of the Maya. Professor David Webster, who helped uncover some of these fortifications, argues that we can no longer view the Maya as models of political stability. However, Dr. Webster also notes that for the average Maya person, warfare was rare, and most likely they only witnessed a few human sacrifices (if any) in their lifetimes.

As for those human sacrifices, while often exaggerated in popular culture, they were undeniably part of Maya history. Evidence supports the practice of infant sacrifices, decapitation rituals, personal bloodletting, and the mutilation of captives in their religious ceremonies.

While these acts might seem shockingly violent from our modern perspective, it’s important to understand them within the context of a vastly different culture. And it’s worth keeping in mind that, during the European conquest of the Americas, tens of millions of indigenous people were killed. Millions more perished during World War I, yet our perception of those soldiers isn’t solely defined by their role as relentless killers.

Despite the violence, the Maya created a thriving civilization within the challenging rainforests of Central America. Although there were significant regional and temporal differences among groups, most Maya cultivated maize as a staple crop, alongside beans and squash. They also introduced the world to corn and corn-based products like tortillas, and they grew cacao, enjoying chocolate drinks made from it.

The Maya were among the first to adopt the concept of zero, or a placeholder, more than a thousand years before it made its way to Europe from the East. They also developed a sophisticated system of hieroglyphics, though much of their written record was destroyed by the Spanish, who considered it heretical. The surviving texts show a deep understanding of astronomy, documenting the movements of stars and planets and even predicting celestial events such as eclipses.

Their focus on time cycles, intricately connected to their religious beliefs, extended to the renowned Maya calendar—or rather, calendars, as the Maya had multiple systems.

4. Myth: The Maya predicted the world would end on December 21, 2012.

The potential apocalypse of 2012 was a major source of panic in the early 2010s. This fear even led to a surge in bomb shelter sales in the U.S., and numerous cults formed worldwide, preparing for the supposed end of days. (We even got a blockbuster movie inspired by the hype.) But despite all the fanfare, December 21, 2012, came and went without any catastrophic event. So, were the doomsayers right to be worried? After all, didn’t the Maya calendar say the world was going to end that day?

First off, the Maya actually had multiple calendar systems, including the 260-day Tzolk’in and the 365-day Haab. These could be combined to form a roughly 52-year cycle called the Calendar Round. When people talk about the “Mayan calendar” ending in 2012, they’re usually referring to the Long Count Calendar, which is different. The Long Count divides time into units like kins (days), uinals (months of 20 days), and tuns (18 uinals). The calendar doesn’t stop at a few years; it stretches on through incredibly long units of time, all the way to the alautun, which equals over 63 million years. (No wonder they called it Long Count.)

The Long Count calendar began with a creation date, typically dated to August 11, 3114 BCE. It also included a major cycle, known as the 13th baktun, which was set to conclude around late December 2012. While this cycle may not have ended precisely on December 21, it’s important to note that there is no evidence suggesting the Maya ever believed this would mark the end of the world.

There are only a handful of known Maya inscriptions that reference this date, with the most notable one appearing on a monument that has been partially damaged and is therefore not entirely legible. Linguists specializing in Mayan languages believe that the reference likely points to a future event, rather than an apocalyptic scenario. At the close of the Baktun, the Maya probably would have simply started a new cycle, as they had done repeatedly before [PDF].

This doesn't mean that the end of the Baktun wouldn't have been regarded as a significant event; it's likely that the Maya considered it an important moment, possibly marking a special occasion.

5. Myth: The Maya vanished without a trace.

Mayan lintel featuring the nine generations of rulers at Yaxchilan, dated between 450-550 CE. | Print Collector/GettyImages

Mayan lintel featuring the nine generations of rulers at Yaxchilan, dated between 450-550 CE. | Print Collector/GettyImagesWhen the Spanish first encountered the Maya in the early 1500s, the civilization had already passed its peak in terms of territorial reach. The reasons for this decline are debated by scholars. Given the diversity of the Maya civilization, which consisted of multiple city-states with distinct challenges, it’s clear that there wasn't a single cause for the downturn. Some regions may not have collapsed at all, while others were entirely deserted. Factors such as drought, deforestation, and warfare likely contributed to a population reduction of as much as 90 to 95 percent from its zenith around 800 CE.

While we may never know the exact cause behind the dramatic population decline during the post-Classic period, one thing is certain: the Maya never completely vanished. In fact, an independent Maya Kingdom persisted and remained unconquered until 1697.

Although the Spanish conquest and the arrival of “old-world” diseases like smallpox further decimated the region's population, around 7 million Maya people still live today. Many continue to speak Mayan languages and maintain aspects of their culture, from spiritual practices to traditional medicine. Some groups escaped forced “Christianization” by fleeing from the Spanish, while others mixed with Europeans and now speak both Spanish and their indigenous language.

Descendants of the Maya civilization make up a significant portion of the population in Guatemala [PDF] and the Mexican state of Yucatan. While the Maya civilization may belong to the past, the Maya people are very much alive in the present day.