During the 17th and 18th centuries, as Western nations sailed across the globe—exploring, trading, colonizing, and enslaving—disasters were commonplace. While some tragedies stemmed from wars or storms, others were caused by internal chaos.

Crews often rebelled, leading to mutinies. Below are five of the most harrowing stories of naval uprisings from that era, including Henry Hudson’s mysterious disappearance and the H.M.S. Bounty’s ill-fated breadfruit mission.

1. The Discovery // 1611

John Collier’s 1811 painting, 'The Last Voyage of Henry Hudson,' displayed at Tate Britain. | Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

John Collier’s 1811 painting, 'The Last Voyage of Henry Hudson,' displayed at Tate Britain. | Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainHenry Hudson’s legacy is etched across northeastern North America, with landmarks like the Hudson River, Hudson Bay, and Hudson Strait bearing his name. For enthusiasts of Hudson’s voyages, these names also evoke the enduring mystery surrounding his disappearance.

In April 1610, Hudson embarked on his final journey from London aboard the Discovery, accompanied by a crew of 24. His mission was to discover the fabled Northwest Passage, a direct sea route connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. By August, the Discovery had reached Hudson Bay via the Hudson Strait, and by November, it had ventured south into James Bay, nestled between Ontario and Quebec. However, the harsh, unexpected cold trapped the ship in pack ice, forcing the crew to endure a grueling winter.

The situation quickly deteriorated. Gunner John Williams died under unclear conditions just weeks into the ordeal. Navigator Abacuk Pricket noted, “God pardon the Master’s [Hudson’s] uncharitable dealing with this man.” Tensions escalated when Henry Greene, a crew member, clashed with Hudson over Williams’s coat and other disputes, including a confrontation with the carpenter over building a shelter. The atmosphere grew increasingly volatile as tempers flared.

The tension persisted even after the ice began to thaw the following spring. Hudson was determined to continue searching for the Northwest Passage, but the crew, desperate and starving, longed to return home. On June 22, 1611, they mutinied, forcing Hudson, his teenage son, and seven others—some ill, others unwilling to rebel—into a small shallop. Hudson attempted to keep up with the Discovery, but it was hopeless, and the castaways vanished forever.

The mutineers didn’t fare much better. Several died in a clash with Inuit people. Among those who made it back to England, four were tried for abandoning Hudson and his companions to their fate—yet all were acquitted and walked free.

2. The Batavia // 1629

A 2007 photograph of a replica of the 'Batavia.' | ADZee, Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

A 2007 photograph of a replica of the 'Batavia.' | ADZee, Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainOn June 4, 1629, the Batavia, a Dutch East India Company (VOC) merchant ship, was wrecked near Beacon Island off Australia’s western coast. While dozens of its approximately 340 passengers and crew died in the disaster, the survivors faced even greater horrors.

The Batavia was en route from the Netherlands to Batavia (modern-day Jakarta, Indonesia), carrying silver coins and other precious cargo. Its mission was to return with spices, but the voyage was plagued by discord. Separated from its fleet, tensions escalated between senior merchant Jeronimus Cornelisz, Captain Ariaen Jacobsz, and fleet commander Francisco Pelsaert, who was aboard the Batavia. Their plot to mutiny was interrupted by the shipwreck.

After Pelsaert, Jacobsz, and around 50 others left in a longboat to seek help, chaos erupted on Beacon Island. Cornelisz, fearing his mutiny would be discovered, aimed to seize any rescue ship and turn it into a pirate vessel. He sent groups to nearby islets, hoping they would perish, and by early July, he and his followers resorted to brutal methods like drowning and throat-slitting to eliminate survivors.

Not all the violence was strategic. Among the Batavia’s passengers were about 20 women, some of whom died in the wreck or shortly after. As Mike Dash noted in Batavia’s Graveyard, the mutineers killed those deemed too old or pregnant, keeping seven women alive to repeatedly assault them.

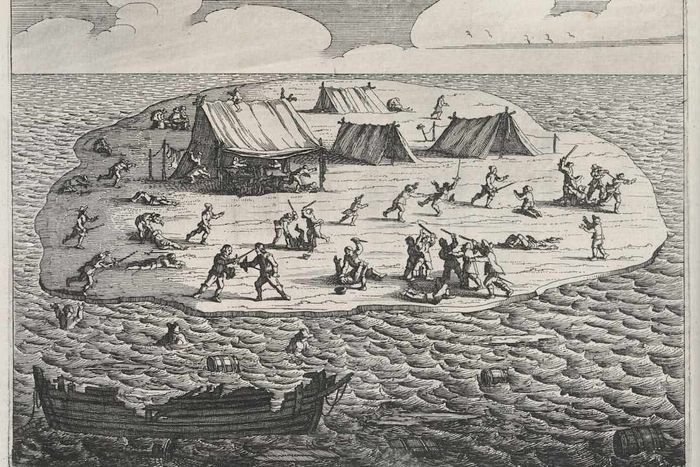

A 1647 depiction of the battle between mutineers and soldiers after the shipwreck, illustrated by Francisco Pelsaert and Jeremias van Vliet. | State Library of New South Wales, Wikimedia Commons // CC BY-SA 3.0 AU

A 1647 depiction of the battle between mutineers and soldiers after the shipwreck, illustrated by Francisco Pelsaert and Jeremias van Vliet. | State Library of New South Wales, Wikimedia Commons // CC BY-SA 3.0 AUCornelisz and his followers killed over 100 people before engaging in a prolonged conflict with soldiers led by Wiebbe Hayes. (Hayes’s group had been sent to a nearby island in a failed attempt to eliminate them while searching for water.) The battle ended in mid-September when Pelsaert returned with a rescue ship.

Pelsaert swiftly captured, interrogated, and sentenced the mutineers. Some were executed on Long Island in early October, while others, along with 77 survivors—including five women and a child—were taken back to the Indies. Cornelisz was among those hanged, and before his execution, both his hands were severed, reportedly using a hammer and chisel, as described in Batavia’s Graveyard.

As Cornelisz faced execution, onlookers shouted “Revenge!” at him, and he defiantly echoed the cry. The presiding pastor noted, “Even as he mounted the gallows, he cried, ‘Revenge! Revenge!’ proving he remained wicked until his final breath.”

3. The Meermin // 1766

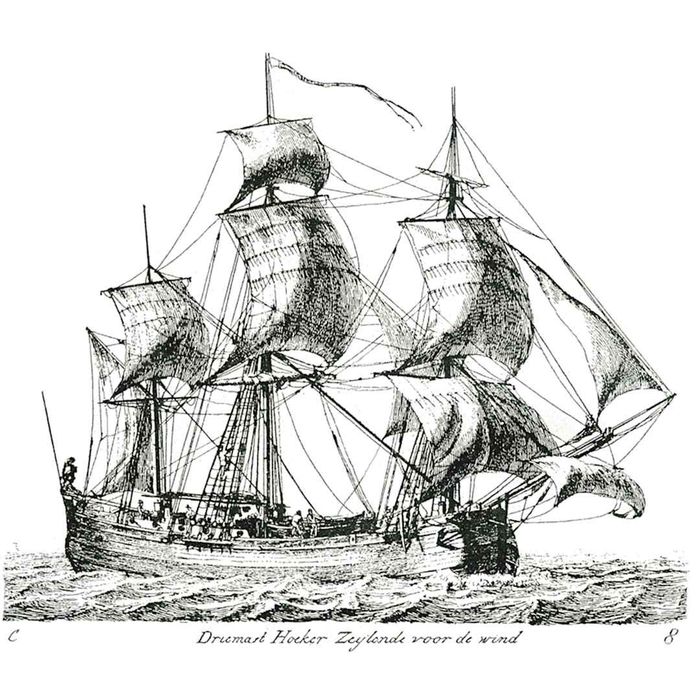

The 'Meermin' resembled this 18th-century Dutch vessel. | Gerrit Groenewegen, Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

The 'Meermin' resembled this 18th-century Dutch vessel. | Gerrit Groenewegen, Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainIn January 1766, the Meermin, a VOC ship, left western Madagascar carrying 147 enslaved Malagasy people bound for Cape Town, South Africa. To reduce deaths and disease in the cramped hold, Dutch officials allowed the captives to work on deck. In a critical misstep, head merchant Johann Krause gave spears to Massavana and other prisoners for cleaning, which they used to seize the ship, killing Krause and nearly half the crew.

The Malagasy rebels ordered the surviving Dutch crew to sail the Meermin back to Madagascar. While the crew pretended to comply, they secretly steered toward South Africa. When land was sighted, a group of enslaved people rowed ashore in two boats to verify their location, intending to signal the ship with three fires if they had reached Madagascar.

However, they had arrived at Struis Bay, a Dutch settlement near South Africa’s southern tip. As the group landed, Dutch settlers killed some and captured the rest.

A week-long standoff ensued, marked by confusion and uncertainty. During this time, the Dutch survivors of the Meermin secretly threw messages in bottles overboard, hoping they would reach the shore. Remarkably, two were found—one instructing officials to light three fires. Seeing the signal, the mutineers steered the ship toward land, but it struck a sandbar, leading to their swift surrender.

Volunteers assisted everyone ashore, where the Malagasy captives were fed and cared for. However, this apparent kindness concealed a darker motive: the Dutch East India Company sought to minimize financial losses by ensuring the enslaved people arrived in Cape Town healthy and fit for sale.

“The fleeting spark of autonomy that had highlighted the humanity of the Malagasy slaves was snuffed out,” Andrew Alexander noted in his 2003 dissertation at the University of Cape Town.

4. H.M.S. Bounty // 1789

The mutiny on the H.M.S. Bounty remains the most renowned maritime rebellion, partly due to its portrayal in three major Hollywood films: the 1935 and 1962 versions of Mutiny on the Bounty and 1984’s The Bounty.

The mutiny occurred in 1789 during a voyage to transport breadfruit plants from Tahiti to the West Indies, intended as a cheap, nutritious food source for enslaved laborers. The Bounty’s crew had enjoyed a five-month stay in Tahiti, with around 40 percent treated for sexually transmitted infections. Returning to the grueling life at sea proved challenging, and discontent brewed, culminating in mutiny before reaching the Indies.

In the early hours of April 28, master’s mate Fletcher Christian led the uprising, forcing Captain William Bligh and 18 others into a small boat and casting them adrift. Though threats of violence were made, no lives were lost, and the mutineers provided the castaways with sufficient supplies, including the carpenter’s toolbox. “He’ll have a new ship built in a month,” one mutineer reportedly remarked.

The mutiny’s exact cause remains debated. Bligh, known for his strict discipline and temper, is often portrayed as the antagonist. His accusation that Christian stole coconuts may have triggered the rebellion. However, Bligh wasn’t excessively harsh during the voyage, and some argue he was simply the target of a disillusioned crew’s frustration.

A 1960 replica of the 'Bounty' photographed in 2008. | Tim Rue/GettyImages

A 1960 replica of the 'Bounty' photographed in 2008. | Tim Rue/GettyImagesThe mutineers’ efforts to find a new paradise ended in failure. Initially, they settled on Tubuai, south of Tahiti, but conflicts with the island’s Native inhabitants forced them to return to Tahiti. After a second failed attempt to colonize Tubuai, they left again, this time without 16 crew members who either stayed behind or were abandoned by Christian, who feared rebellion. The mutineers also deceived nearly 20 Tahitians into boarding the Bounty under false pretenses.

In 1790, they finally established a colony on Pitcairn Island, an uninhabited volcanic island southeast of Tahiti. However, tensions arose as the Tahitian captives resented the Englishmen’s mistreatment of their women. This conflict escalated in September 1793, leading to the murder of Christian and three others. By 1808, when an American whaling ship discovered the settlement, only John Adams (not that one) remained of the original mutineers. He lived there until his death in 1829, and today, Pitcairn is inhabited by around 50 descendants of the original settlers.

Bligh fared better than most. He and his crew sailed 3600 miles over 47 days, reaching the Dutch-controlled island of Timor in June. One man died during a conflict with the people of Tofua, and several others succumbed to fever after arriving in Timor. Bligh, however, returned to England and enjoyed a successful naval career until his death in 1817.

5. H.M.S. Hermione // 1797

The 'Hermione' after Spain renamed it the 'Santa Cecilia.' | Thomas Whitcombe, Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

The 'Hermione' after Spain renamed it the 'Santa Cecilia.' | Thomas Whitcombe, Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainWhile the Bounty is more widely known, the bloodiest mutiny in British naval history took place on the H.M.S. Hermione in September 1797. The frigate was patrolling the Mona Passage—the strait between Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic—during the French Revolutionary Wars.

Captain Hugh Pigot, a 28-year-old tyrant, was the primary issue. His excessive use of flogging, which had previously resulted in the deaths of two men, pushed the crew to their limits. After about seven months under his command, the Hermione’s 180-man crew had endured enough.

The tipping point came when Pigot confronted midshipman David Casey about the topmen’s failure to follow rigging protocol. Casey explained the need to secure a loose gasket, but Pigot insulted him and demanded he kneel and beg for forgiveness. Casey’s refusal led to 12 lashes and his demotion. Pigot then targeted the topmen, many of whom were also flogged.

On the night of September 21 or 22, after drinking rum and plotting, a group of mutineers attacked Pigot with axes and other weapons, throwing him overboard while he was still alive. “Aren’t you dead yet, you bugger?” one shouted, while another declared, “You’ve shown no mercy and deserve none!” The mutineers also killed nine officers.

The mutineers steered the Hermione to La Guaira, a Spanish port in present-day Venezuela, and later dispersed to secure work for their survival. Over the following decade, British authorities captured 33 of the rebels, executing 24 by hanging.