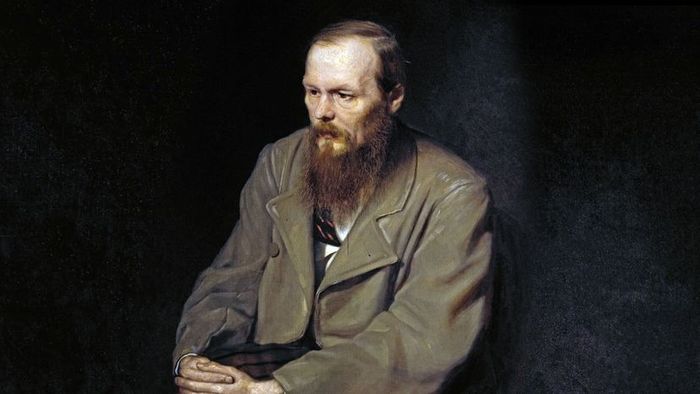

A striking 1872 depiction of Fyodor Dostoevsky, housed in the Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia. Courtesy of VCG Wilson/Corbis via Getty Images

A striking 1872 depiction of Fyodor Dostoevsky, housed in the Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia. Courtesy of VCG Wilson/Corbis via Getty ImagesOn December 22, 1849, Fyodor Dostoevsky, aged 28, was led from a grim St. Petersburg prison into the freezing air and positioned before a firing squad. Moments from death, he reflected on his two published novels — one a triumph, the other a failure — and the unfulfilled potential of his literary aspirations.

As the soldiers prepared to fire, a carriage arrived bearing a white flag. A messenger announced that Czar Nicholas had granted Dostoevsky and his fellow revolutionaries a reprieve. Instead of execution, they would endure four grueling years in a Siberian labor camp, trading instant death for prolonged suffering.

After his time in Siberia, Dostoevsky emerged transformed. He had confronted death and witnessed the extremes of human cruelty, yet his faith in God and the transformative power of love remained unshaken, even strengthened.

"The common portrayal of Dostoevsky as a brooding, ailing Russian novelist of dense works overshadows the complexity of his true character," notes Alex Christofi, writer of "Dostoevsky in Love: An Intimate Life," a biographical exploration of the author's personal journey.

While Dostoevsky battled severe epilepsy and a gambling habit, he was also a loving family man who discovered profound happiness with his second wife, Anna, his partner and confidante. His masterpieces, such as "The Brothers Karamazov," "Notes from Underground," and "Crime and Punishment," not only defined existential thought but also influenced psychological discourse.

Here are five illuminating quotes from Dostoevsky's life and writings that offer a glimpse into his true essence:

1. "Literature is a picture, or rather in a certain sense both a picture and a mirror."

In 1846, Dostoevsky penned a letter to a friend, celebrating the triumph of his debut novel, "Poor Folk," from which the aforementioned quote originates. The book had just been released to glowing reviews and impressive sales. "If I tried to list all my achievements, I wouldn’t have enough paper," he wrote.

"He instantly became a literary phenomenon," remarks Christofi.

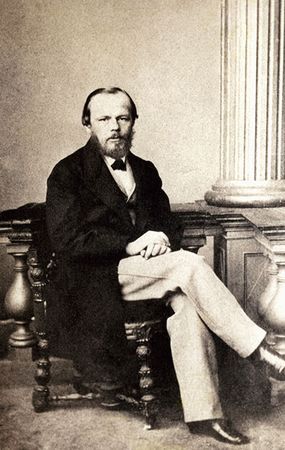

A photograph of Fyodor Dostoevsky, taken around 1865. His works profoundly influenced figures like Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Anton Chekhov, Friedrich Nietzsche, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Albert Camus.

adoc-photos/Corbis via Getty Images

A photograph of Fyodor Dostoevsky, taken around 1865. His works profoundly influenced figures like Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Anton Chekhov, Friedrich Nietzsche, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Albert Camus.

adoc-photos/Corbis via Getty ImagesDostoevsky's early life was marked by hardship. He spent his formative years in Moscow, largely at a hospital for the impoverished where his father worked as a physician. At school, he often drifted into daydreams and faced bullying from wealthier peers. Tragedy struck when his mother passed away from tuberculosis at 15, followed by his father’s murder two years later.

After being orphaned, Dostoevsky graduated from a military academy and worked as an army engineer ("though not a particularly skilled one," Christofi notes), but his true passion was writing, inspired by his idol, Nikolai Gogol. He penned a manuscript that would later become "Poor Folk," and a friend shared it with the renowned critic Vissarion Belinsky, who hailed it as a masterpiece.

Following the triumph of his debut novel, Dostoevsky was briefly celebrated by Russia's literary elite and left his engineering career. However, when his next novel failed to impress, his newfound acquaintances mocked his peculiar behavior and speech. Dostoevsky, who was slight, pale, and frail, had also begun experiencing epileptic seizures during his teenage years.

"Dostoevsky soon became involved with a more radical group of writers who held gatherings to discuss ideas opposing the czar, which was highly dangerous," explains Christofi. This marked the beginning of Dostoevsky's serious troubles.

Full quote: "Literature is a picture, or rather in a certain sense both a picture and a mirror; it is an expression of emotion, a subtle form of criticism, a didactic lesson and a document." "Poor Folk" (1846)

2. "A murder by sentence is far more dreadful than a murder committed by a criminal."

The quote above is from "The Idiot," a novel written years after Dostoevsky's brush with death and his harrowing four-year experience in Siberia. It captures how his arrest and imprisonment left an indelible mark on his life.

Dostoevsky and his group of radical thinkers were betrayed by a spy working for the czar's secret police. Convicted on fabricated "conspiracy" charges — driven by Czar Nicholas's fear of a rebellion akin to the failed 1825 Decembrist Revolt — Dostoevsky and his comrades were condemned to execution by firing squad.

The sudden pardon was later exposed as a staged "mock execution," designed to inflict psychological torment on the prisoners and foster a false sense of gratitude for the czar's supposed "clemency."

Though we can't be certain of Dostoevsky's exact thoughts as he faced the firing squad, a character in "The Idiot" observes a guillotine execution and imagines the condemned man's perspective, stating, "[T]he greatest agony may not lie in the physical pain but in the certainty that in an hour, then ten minutes, then half a minute, then now, this very instant — your soul will leave your body, and you will cease to exist."

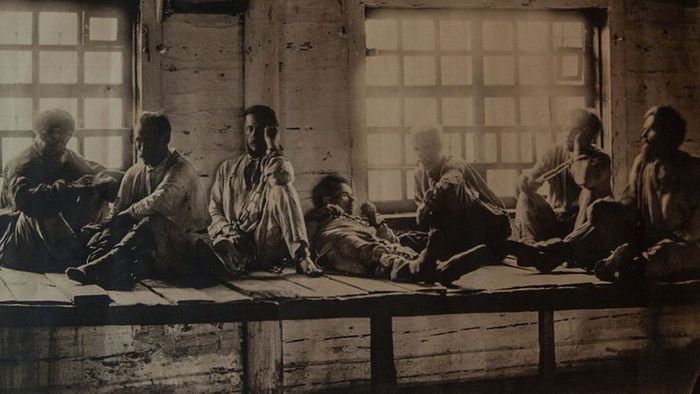

Dostoevsky's four years in a Siberian prison were unimaginably brutal. He was confined with the most violent criminals, his hands perpetually shackled. The filthy, overcrowded cells were nightmarish, made worse for Dostoevsky by the denial of access to books.

Dostoevsky endured imprisonment in this notorious Siberian jail, which is now a tourist attraction.

Alexander Aksakov/Getty Images

Dostoevsky endured imprisonment in this notorious Siberian jail, which is now a tourist attraction.

Alexander Aksakov/Getty Images"He had the New Testament with him, though," Christofi explains. "During his time in prison, Dostoevsky delved deeply into his spirituality as an Orthodox Christian. This profound introspection became a recurring theme in much of his later work, including his most celebrated novels."

Bonus quote: "Man is a creature that can get accustomed to anything, and I think that is the best definition of him." "The House of the Dead" (1861)

3. "I would sooner remain with Christ than with the truth."

When Dostoevsky was freed from prison in 1854, many of the "radical" ideas that once alarmed the czar had become fashionable among young European intellectuals and authors.

"Atheism, along with emerging political ideologies like socialism and utilitarianism, which dismissed religion, was in vogue at the time," Christofi explains. "In this context, Dostoevsky stood out for his unwavering commitment to Christian faith." In a prison letter, he declared that even if someone proved Christ was separate from the truth, he would choose Christ over the truth.

Having spent much of his life among the impoverished, Dostoevsky empathized with utopian movements striving for a fairer society. However, he feared the consequences of dethroning God and placing humanity in His stead. This was decades before the Bolshevik Revolution and the emergence of a totalitarian communist state that, under Stalin, imprisoned and executed millions.

"Dostoevsky was deeply convinced that an atheistic socialism would inevitably lead to violence," Christofi notes. "In this regard, he proved remarkably prescient."

Bonus quote: "If there's no God and no life beyond the grave, doesn't that mean that men will be allowed to do whatever they want?" "The Brothers Karamazov" (1879)

4. "I admit that twice two makes four is an excellent thing, but if we are to give everything its due, twice two makes five is sometimes a very charming thing, too."

This line is taken from "Notes From Underground" (1864), Dostoevsky's retort to the widely acclaimed philosophical novel "What Is To Be Done?" by fellow Russian author Nikolai Chernyshevsky.

Though Chernyshevsky is not widely remembered today, in the 1860s, his utopian visions inspired early socialists, utilitarians, and future communists. He believed human behavior was governed by the same rational, scientific principles as the natural world.

"If everyone simply follows their rational self-interest, the world will transform into a paradise, and we can discard irrational notions like God," Christofi explains. "But this assumes humans are mechanical beings who always act in the most logical way."

Dostoevsky, based on his own experiences, knew this wasn't true. As the quote above illustrates, people sometimes insist that two plus two equals five, simply to assert their freedom.

"Sometimes individuals act irrationally, simply to assert their freedom," Christofi observes.

Dostoevsky often acted against his own rational self-interest. He was, for instance, a compulsive gambler. Today, we might diagnose this as a gambling addiction, but Dostoevsky simply couldn't resist the allure of roulette. Whether he had money or was drowning in debt, he gambled, losing far more than he ever won. Such behavior was anything but rational.

The unnamed protagonist of "Notes from Underground" was a bundle of contradictions, a "free" individual who struggled to fit into society. If allowed to follow his "rational self-interest," the outcome would be disorder, not harmony. Dostoevsky expanded on this theme in "Crime and Punishment," his first major novel, where a man's coldly calculated plan to murder an elderly woman for financial gain spirals into disaster.

Bonus quote: "There exists no greater or more painful anxiety for a man who has freed himself from all religious bias, than how he shall soonest find a new object or idea to worship." "The Brothers Karamazov" (1879)

5. "What is hell? I maintain that it is the suffering of being unable to love."

This quote originates from Dostoevsky's final and most celebrated work, "The Brothers Karamazov." "While we often picture Dostoevsky as a prolific writer, constantly writing or debating with his peers, he actually spent much of his life searching for a life partner to build a family with," Christofi explains.

Anna Snitkina, a stenographer, married Dostoevsky in 1867 shortly after assisting him with his novel "The Gambler," which he dedicated to her.

Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images

Anna Snitkina, a stenographer, married Dostoevsky in 1867 shortly after assisting him with his novel "The Gambler," which he dedicated to her.

Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty ImagesDostoevsky's first marriage was to a widow named Maria in 1857, but they quickly realized they were ill-suited and unhappy together. Maria passed away in 1864, the same year Dostoevsky lost his brother, Mikhail, leaving him financially responsible for Maria's son and Mikhail's family.

In a desperate attempt to settle his and Mikhail's debts, Dostoevsky agreed to write a short novel within a year. However, he spent 11 months focused on "Crime and Punishment." With just one month remaining, he hired a stenographer to transcribe his rapid dictation of the novel.

The young woman he employed, 20-year-old Anna Grigoryevna Snitkina, became not only his trusted literary collaborator and business manager but also the great love of his life. Anna and Fyodor wed in 1867 and had four children, though only two lived to adulthood.

"After witnessing all he endured — the mock execution, Siberian imprisonment, and his gambling struggles — it feels deeply satisfying to see him finally discover love," Christofi remarks.

With Anna by his side, managing their finances, Dostoevsky released "The Brothers Karamazov" in 1879. The expansive novel achieved tremendous commercial success.

"'The Brothers Karamazov' was a massive sensation at the time," Christofi notes. "It cemented Dostoevsky as one of Russia's most celebrated authors. When he passed away in 1881 [due to epilepsy], tens of thousands lined the streets of St. Petersburg for his funeral. Onlookers even wondered if they were burying the czar."

Bonus quote: "Beauty will save the world." "The Idiot" (1869)

Mytour receives a modest affiliate commission from purchases made through links on our website.

When Dostoevsky gambled away their earnings, Anna assumed control of the business aspects of his writing career and transformed Dostoevsky into a national 'brand,' making him Russia's first self-published author.