From the eccentric Dr. Frank-N-Furter to the quirky Dr. Doofenschmirtz, tales of mad scientists and their bizarre experiments have captivated us for decades. History shows that these seemingly fictional characters have real-life counterparts. Let’s delve into six groundbreaking experiments born from both brilliant minds and unorthodox thinking.

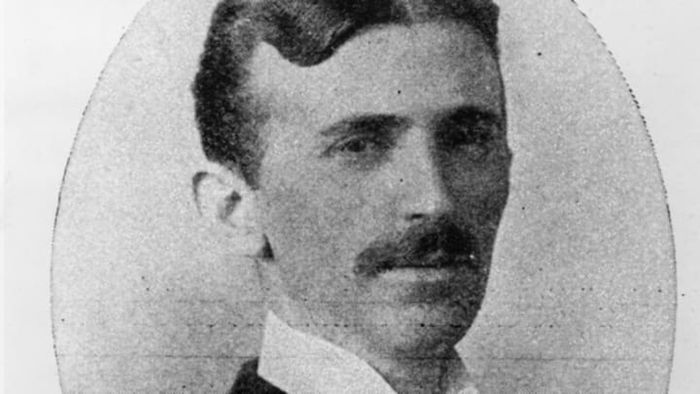

1. Nikola Tesla’s Revolutionary Death Ray

While shrink rays, heat rays, and ray-guns are staples of science fiction, they’ve also sparked real-world innovation. In 1931, Nikola Tesla announced the creation of a functional "death ray." Though not the first to attempt such a device, Tesla’s version was unique because it potentially worked. His invention used charged particles fired from a vacuum chamber, a method he believed would render the device harmless.

"There are still a few final touches needed—my current calculations might be off by around 10 percent," he stated in 1934. However, he was confident that once perfected, "a nation’s entire border could be safeguarded by installing one of these beam-producing units every 200 miles."

2. Vladimir Demikhov’s Two-Headed Canine Experiment

WARNING: THE FOLLOWING CONTENT IS DISTURBING.

Vladimir Demikhov pioneered vital-organ transplants, beginning with heart and lung transfers between animals before advancing to more complex procedures: head transplants. In 1954, he achieved a groundbreaking feat by grafting the head, shoulders, and front legs of a puppy onto an adult dog’s neck. Both heads maintained consciousness and functioned independently, eating and drinking until the hybrid creature succumbed a few days post-surgery. Demikhov replicated this unsettling experiment multiple times, with the longest survivor living for one month.

3. Gabriel Beaurieux’s Fascination with Decapitated Heads

Gabriel Beaurieux’s research might evoke memories of Henry VIII and his numerous wives. In 1905, Beaurieux witnessed the execution of a prisoner named Henri Languille. He observed that, post-decapitation, the head retained consciousness and movement for a few seconds, even opening its eyes twice when called by name. Beaurieux recounted:

The head landed on the severed neck surface, so I didn’t need to lift it with my hands, contrary to what many newspapers claimed. I didn’t even have to touch it to position it upright. Fortune favored my observation. ... The eyelids and lips of the decapitated man twitched in irregular, rhythmic spasms for about five to six seconds. ... After a few moments, the movements stopped. The face relaxed, the eyelids half-closed, revealing only the whites of the eyes, much like the dying patients we often encounter in our profession or those recently deceased. At that moment, I called out loudly: “Languille!” I watched as the eyelids slowly lifted.

Kids, do not attempt this experiment at home.

4. Sergei Brukhonenko’s Canine-Headed Machine

WARNING: DISTURBING CONTENT.

Sergei Brukhonenko, a Soviet scientist, created an innovative device called the "autojector," a heart-lung apparatus designed to sustain the life of a dog’s head after its separation from the body. During demonstrations, the isolated head reacted to light and sound stimuli and even consumed a piece of cheese. Brukhonenko asserted that he could drain the head of blood, leave it inactive for ten minutes, and then revive it using his machine. A remarkable feat indeed.

5. Stubbins Ffirth’s Dangerous Vomit Experiment

In the early 1800s, Stubbins Ffirth, a medical student in Philadelphia, dedicated his studies to yellow fever, a disease that had ravaged the region years earlier. Convinced that yellow fever was non-contagious, Ffirth tested his theory by exposing himself to the vomit of infected patients—applying it to his eyes, self-inflicted wounds, and even ingesting it. Contrary to his belief, yellow fever is contagious through blood transmission, making it astonishing that Ffirth never contracted the illness. Luck, it seems, was on his side.

6. Winthrop Kellogg’s Chimpanzee Child Experiment

Mad Science Museum

While Tarzan explored the idea of a boy raised by apes, Winthrop Kellogg flipped the script by raising a chimpanzee, Gua, alongside his infant son, Donald, in 1931. Treating Gua as a human child, Kellogg conducted regular developmental tests on both. Gua outperformed Donald in nearly every area except language. Intriguingly, Donald began mimicking Gua’s "food bark" to express hunger instead of speaking. The experiment ended prematurely, and Gua was returned to the primate center.